main: September 2005 Archives

Anonymous: 9/11 Shrineat Ground Zero, 2001. (Photo: J.Perreault)

Where Were You?

Artist responses to 9/11 are, I suspect,as varied as lay responses. Defiance, withdrawal, denial, bewilderment. And good, old-fashioned anger. But somehow we expect artists to express their feelings in their work, whereas we do not ask the same of farmers, cable guys, nurses, clerks, engineers, and stockbrokers. Or philosophers.

On the other hand, everyone has a 9/11 story.

Herein I must relate my own moment of truth, to provide some context. I saw the first plane hit on television when I was about to get out of the door on my way to work. I am old enough to remember when an airplane hit the Empire State Building. Did I also see that on television -- black and white -- or only later in the Daily News?

In any case, on September 11, 2001, I thought: how weird, but I'd still better get to work. If the subway to Brooklyn is running I'll continue on. After all, as the boss, I had better be there if there is any further emergency. I remember thinking, should I, as usual, stop at my gym at Bowling Green? I was already late. But the train mysteriously stopped dead at Bowling Green, which is at the tip of Manhattan. We were ordered to leave the cars. On the platform, there were weeping people lined up at the pay phone trying to reach...their offices or their loved ones? What was going on?

An announcement over the p.a. system, for once understandable, urged that we stay where we were, which was several levels beneath Bowling Green, never a pleasant prospect. And then in one of those moments of clarity, I smelled something acrid: burning wires. I was getting out of there no matter what; I was the first to mount the stairs. And then ...

Suddenly I was in Alaska, except it wasn't cold. Everything was covered with inches of white ash, and I saw ash-covered zombies in ash-covered business suits parading by, through the ash-covered streets. They had no race; everyone was white. A bullhorn urged that we walk east and then follow the river. I too pulled out my undershirt from under my now-untied tie and my starched shirt to cover my nose and my mouth.

Further east the air cleared, and I was treated to the spectacle of business folk first cursing their cell-phones then banging them and sometimes smashing them on any available surface. Suddenly, not quite at the Fulton Street Seaport, people were running down an alley toward me; a World Trade tower looming above them in the not so distant distance: They were screaming:It's going! The second one is coming down!

In the quickestmath I have ever used, my brain instantly compared the height of the tower and my distance from the base. Not knowing that the first tower had imploded, I pictured the tower toppling like a giant tree and landing on top of me. I ran, my snowstorm trance broken,

Next I saw tiny silhouettes, as if in a Roger Brown painting, crossing over to Brooklyn on the Brooklyn Bridge. Coming to my senses, I decided that hiking back home to the East Village would be wiser than trudging over the East River to downtown Brooklyn, where my workplace was. So much for my unexpected "captain of the ship" syndrome. If trapped, could I bear an Urbanglass sleepover?

Second Avenue, when I finally got there, was eerie. The silence was so thick you could cut it with a bread knife. Except there was already almost no bread in the supermarket or any of the convenience stores. (I did find a last square package of organic pumpernickel in the 9th Street Indian-run all-night place. Even the threat of starvation would not get anyone but me to grab that particular rock.) All the milk had gone missing, too. Tells you something, right? Bread and milk before steak and eggs, before booze and butter.

My beloved was in Philadelphia, and how we finally regained contact is another story. But somehow we did. He wrote his end of the tale for the Philadelphia Inquirer.

And now, much later, it's clear my life was changed. Good-bye day job; hello blog. Good-bye arts administration, hello art. Goodbye magazine editing; hello poetry. This is, of course, a simplification, but it is the truth. It took a while and some sleight-of-hand to work myself free, but within a year I was in the clear.

Installation View: The Art of 9/11 at apexart

Just A Few Friends

Now perhaps we are far enough away to look at some art. Or obviously so, thinks philosopher/art critic Arthur Danto. His "The Art of 9/11" at apexart (291 Church St., to Oct. 15) gathers a few works made by artists right after 9/ll. I like Robert Rahway Zakanitch's "decorative" paintings, because he is the best paint handler, abstract or not, now going. And as much as we hate clowns, we love Cindy Sherman done up as one, sensing that she, like Bruce Nauman -- and yours truly -- hates and fears clowns too.

This is not a show of memorial art. That's a whole other subject. It is instead, I think, an exhibition of the adjacent. The deep question here is not so much how art can memorialize, but how we discern meanings and intentions without the apparatus of the verbal. In Danto's exhibition this becomes the subject. He has grouped together what some of his artist acquaintances made immediately after 9/11, thus foregrounding a problematic.

In trying to parse works by Lucio Pozzi and also Audrey Flack, works that have no obvious connection to 9/11 (Flack offers watercolors of fishing boats in Montauk Harbor), you have to read their statements, which are mostly 9/11 stories. Danto admits: "That is how it is with religious acts. One has to know the spirit in which they are performed to grasp their cultural meaning." In fact, some works do have a visible relationship to the event: Barbara Westman's Memory Piece, a depiction of the memorial light towers (to my mind now the only 9/11 memorial we really need), and Leslie King-Hammond's altar. Mary Miss's Moving Perimeter: A Wreath for Ground Zero, once the subtitle is removed, could be an outdoor artwork anywhere for any purpose. Pozzi actually showsphotographs of 9/11 smoke on Mulberry Street, and Jeffrey Lohn rephotographed photographs of the missing posted after the catastrophe.

Danto, however, is particularly eloquent here and, closer to 9/11, in The Nation in his understanding of the spontaneous altars that were created around the city right after 9/11. Some, as on my block, reappear at every 9/11 anniversary: words, candles, and flowers. Unlike most art, they allow no ambiguity. My question is: Are they then really art?

Nevertheless, Danto's phrase "the spirit in which they are performed," offered up in conjunction with his collection of post-9/11 art, is suspiciously like rooting out intentions. We in literature have long been warned of the intentional fallacy.

I would rephrase the issues in the following way. What is the form of grief? What is the color of anger? We need to turn the problem inside-out. Isn't the spiritual part of religious art the making of that art? Is there a technology of the spirit that utilizes the visual?

What holds art back? Fear. Fear of sentiment (or emotion). Fear of producing propaganda. Fear of being pinned down: your opinions may one day be used against you. Not having the right vocabulary to express outrage, grief, fear. Or: dismay.

Artist responses in Danto's show seem to be one species or another of "life -- i.e. art; my art -- must go on." Does this mean that art at some very deep level means hope? Yes. Is art therefore a faith in the future, or a magical effort to assure there will be a future? Yes, up to a point, but I don't think this means that if there were no future, artists would stop making art. Art-making is about confirming the present, too, and making it sacred or revealing it as such, no matter what.

* * *

Another 9/11 exhibition takes a more traditionally activist approach: the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council's "A Knock at the Door" (at Cooper Union, Astor Place; and the South Street Seaport Museum, to Oct. 1). Here, as in Danto's show, the viewer needs to do a lot of reading: anonymous boxes stenciled with the phrase "Fear Art" at both sites work; as dobanners at the Seaport Museum showing persons abused in one way or another by the Patriot Act and its atmosphere of fear.

We know -- or should know -- the Steve Kurtz story. Kurtz is a member of the extremely serious and Artopia-approved Critical Art Ensemble. When he called the police to let them know his wife had just died of a heart attack, he was arrested for bioterrorism. Why? One Critical Art Ensemble theme has been genetic alteration of plants. And somehow the officials in charge thought Kurtz -- apparently already under survaillance --was making a biological weapon. One entry in this extremely inclusive exhibition is a replication of Kurtz's books seized by the FBI.

Danto's exhibition is, curiously enough, about reaffirming art's importance even when there is an apparent withdrawal from the world; curator Seth Cameron's "A Knock at the Door..." is a reaffirmation instead of the values those behind the 9/11 culprits were hoping to destroy. Freedom of speech is anathema to dictatorships of all kinds. Abuses of the Patriot Act, alas,aid their cause. Why U.S. government agencies time and again fasten on artists is beyond me. Is it that artists are always under suspicion, are weak? Are dangerous? Not the ones I know. A reminder: we have rules and laws not only to protect ourselves from each other, but to protect ourselves from our government. Others are not so lucky.

Arthur Danto's essay is online at apexart.org. Statements by the artists are available at the gallery only.

Seth Cameron's autobiographical and extremely clever essay is part of the LMCC handout, which also includes advice from the American Civil Liberties Union: Know Your Rights: What to Do If Questioned by Police, FBI, Customs Agents or Immigration Officers.

Anonymous: East Village 9/11 Shrine, 2001-05. Photo: J.Perreault

Robert Smithson: Floating Island...

Dead Man's Float

Thirty-five years in the making, Robert Smithson's Floating Island to Travel Around Manhattan Island is being tugged along the Manhattan through next weekend (to Sunday, Sept. 25). Smithson, as we know, died in a plane crash in 1973. In 1970, the same year he created his masterpiece The Spiral Jetty, a curl of rocks jutting from the shore of the Great Salt Lake in Utah, he also made the modest drawing that is the basis for Floating Island.

The Smithson retrospective is still at the Whitney -- you can check out what I wrote when it opened. The Floating Island is a good reminder to see this essential exhibition before it closes (Oct. 23), but it is more than that. What a great way to begin the art season! Perhaps the comatose art world is waking up at last after the shock of 9/11. There is indeed more to art than the same-old graduate student "bad" paintings -- which no longer look willfully inept and ironic, but simply bad -- and the proliferation of pathos.

But last Friday, drenched with humidity, I was on the good-ship Abigail K to view the Floating Island at nightfall. Because of late-arriving guests the yacht was a wee bit tardy in pulling out from its moorings; but Nancy Holt, Smithson's partner and an artist in her own right, had told me to stay at the prow to get the best view of the tugboat-tugged art barge, timed to be nearby as we embarked.

And there it was, closer to the shoreline than expected: an eerie silhouette of floating, living trees. And later, as we toasted the Whitney, Minetta Brook (a nonprofit dedicated to art along the Hudson River), the James Cohan Gallery, the moon and the Statue of Liberty, and dined in the middle of New York harbor, our yacht and the Floating Island did a kind of stately, ghostly pas de deux. Of course, outlined against Manhattan's cliffs of light, the Floating Island hadbecame an unphotographable, unforgettable silhouette. What could the people on pleasure boats and ocean liners and real workaday tugs and barges have made of this strange sight? I wondered too what tourists and ordinary Joes and Janes, in daylight on the shoreline, would make of the serenely plying chunk of park floating by on their lunchtime breaks or on the square screens of their cell-phone cameras. Would they know it was art?

In the '60s, when I was involved with Streetworks -- objects or performances that ordinary passersby might stray upon on any given streets -- this was a primary question: Seen outside of a gallery or a museum, how much do you have to know to identify what you are looking at as art? Do you carry an art context around in your head?

Yes, given a little bit of education and experience, but also because, as I often explained to my students, "If you don't know what it is, it's probably art."

Robert Smithson: Floating Island...(1970)

Displacements, Replacements

Last week, as I prepared for adventure and a little cruise around New York harbor, The Times had already weighed in with a cunning preview of Floating Island in the Weekend Section; and there was even a pro-Floating Island editorial. Was that a first? Art can make us see. One speaker on the celebratory yacht confessed that although she had been raised on the Upper East Side (of course), it never dawned on her until now that Manhattan was really an island.

Floating Island is an artwork that is an island meant to circle an island. It is also, as many have pointed and will continue to point out, a displacement of sorts that calls attention to Vaux and Olmsted's (surprise!) totally designed and totally artificial Central Park. I like calling the new artwork a floating synecdoche, a scenic synecdoche, to point out (1) the poetic affect and (2) the theatrical effect.

In fact, several of the boulders on the barge wereborrowed from that lovely 19th century swathe that is the "nature" New Yorkers best know and love: our beloved Central Park. Real nature is in comparison a bit disappointing; hills and rills and little ponds are never where they look best, although camera viewfinders or screens can compensate for bad planning. The borrowed boulders on the Smithson barge, I hasten to add, will be returned to Central Park, and the full-grown trees will be planted where needed. Two weeks and Floating Island is gone.

Yes, as Smithson and I agreed, Frederick Law Olmsted, co-author of Central Park and sole author of Prospect Park in Brooklyn, was one of the most important artists of 19th century America. His work can be seen as a precedent for Earth Art and therefore for Smithson. If genealogy is all (or at least a foothold), then let us think of Olmsted as Smithson's grandfather.

Because of the celebratory nature of the yacht's-eye view (during which I met up with a few old artist friends) and because of the ephemeral and Victorian, folly-like nature of the artwork itself, I fell through a hole in time and found myself at some Baroque water-pageant. But it was a science-fiction Baroque, never before seen, a triumph of imagination over time.

* * *

More pages from My Art Diary

John Perreault: Hair Veil, 1969

Recently, I was in Boston for the opening of "Pattern Language," a broad survey of clothing as art at Tufts University Art Gallery. I am no stranger to the genre, having produced my HairLine of 1969 as part of "The Fashion Show Poetry Event" of that year, recently documented in the Americas Society anniversary exhibition (through Oct. 8).Two modules of hair became in turn a dress, a veil, etc.

My Hair Veil is at Tufts until Nov.13 and will travel to three other university museums. I am thrilled to be in an exhibition with Joseph Beuys, represented by his Felt Suit multiple (1970) and with Yoko Ono, whose Cut Piece (1964) was playing on a video monitor right next to my spooky hank of hair.

We came by Amtrak, we saw, we ate. One might think that all that critics and artists do is go to dinner parties. Not true. But it is part of the territory.

Once in Boston, I couldn't resist going to the Boston MFA to see one of my favorite paintings, Uncle Paul's Where Do I Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? (1897-1898). It seemed appropriate, since Gauguin has visited, inhabited, haunted Artopia several times this summer. Now I can add that his masterpiece is probably a theosophical allegory, at least according to H. P. B., Sylvia Cranston's biography of Helen Blavatsky, which I recently reread.

Also, I had forgotten that the MFA has so many lovely Doves. How's this for best painting title of the last century: Arthur Dove's 1941 Neighborly Attempt at Murder.

I was happy to see Winslow Homer's Long Branch, N.Y. (1869). Art and life intertwine. I was recently in Bradley Beach to deliver five of my polluted-sand seascapes to an exhibition called "Under the Rug, Over the Top" at the Shore Institute for Contemporary Art. Remembering the Homer painting, I swung around in my Honda to take a look at the present-day Long Branch beach. It is still an impressive strand, but now there are giant condos peering down at the funky-'50s Fountain Motel, and these retirement cliffs of brick and glass are almost toe-to-toe with the sand.

Note: Must get some Bradley Beach sand for a new painting in homage to Winslow Homer. Are there any islands of oil-spill as on Fire Island or, obviously raked, is it all cleaned up?

But before I forget, the controversial exhibition of the moment at the MFA is "Things I Love: The Many Collections of William I. Koch." There are some great paintings now owned by this self-identified Godzillionaire that any museum would covet. Artopia is not upset about blatant pandering. Let those who object come up with the cash to purchase the paintings that the MFA hopes will be donated.

And I do not object to Koch's America's Cup boats in front of the museum. Boats have their own beauty. Or to the wine bottles inside. Or even to cowboy art. I too am a collector: midcentury American dinnerware, Southern folk pottery, shell art, lightning rods, and gearshift knobs. So I know the madness.

What I do object to is the wall text that claims Koch collects viscerally and quotes him as saying he does it "to have things around me that remind me of happy feelings and make me feel comfortable, peaceful, pleasant." Comfortable? Is comfort a criterion for collecting art? Not for the art Artopia celebrates; not for the art of the major modernists or postmodernists Someone should have protected Koch from himself here. Surely there are more important reasons to collect: The creation of a legacy, research, preservation, the thrill of the hunt.

But didn't I just write that art and life intertwine? I will use this unfortunate quote in my collectors' seminar at the Phoenix Museum of Art next spring, called "Jump-Start for Contemporary Art: 75 Names You Need to Know," the motto of which is: No question unanswered; no answer unquestioned.

The Past Is Another Place

I could tell it was going to be one of those adventures. Sylvia Sleigh, a painter I've known for many years, phoned me about going to the opera this fall. Sylvia at 89 goes to the opera a lot. Her late husband, the art critic Lawrence Alloway, had hated opera, so she is making up for lost time. I hated opera queens more than I hated opera. I simply could not get interested in the eternal question of who is greater, Callas or Tebaldi? I think Schwarzkopf is greater than both; and as for tenors, I prefer counter-tenors.

But then one thing led to another, and I apologized to Sylvia for not having seen her show at Snug Harbor yet. Well, she said, Nancy and Arlene are driving me over to Staten Island. I need to take some pictures, and they haven't seen the show yet either.

When,I asked?

Tomorrow!

Was there room for me?

Even though I took the R to Battery Park, the ferry and then the bus for four years when I was visual arts director at Snug Harbor Cultural Center, in this day and age, particularly in the deadly, gloomy, global-warming heat, Staten Island seemed far away indeed. So I jumped at the chance. Besides, I had not seen Arlene Raven and Nancy Grossman for quite awhile. When was it that they had moved to the depths of Brooklyn? But I seem to have known them forever. Raven is an important feminist art critic and historian; Grossman is celebrated for her leather heads, which some find disconcerting, particularly since one appeared to have been on the premises of a particularly gruesome art-world crime scene. Never mind about that, to me they have always seemed more about personal anguish and anger than about bondage.

The next day the two gals from Brooklyn pulled up at Sleigh's Chelsea brownstone in a huge, late model BMW. Black, of course. Tiny, talkative Grossman was at the wheel, and we gabbed our way to the Battery Park Tunnel, the Verazzano Bridge and all around Bay Street to Snug. Sleigh held forth too. And Raven, also in the back seat, had many requests for more ventilation, or less. The air conditioner was, even when on, doing weird things.

It was a good thing I had come along; Grossman had left the driving instructions, concocted by Sleigh's studio assistant, back home in Brooklyn in their converted lumberyard. Both Sleigh and Raven were disappointed at the lack of car-carrying ferries. One more romantic thing about New York has bit the dust. Was it in the name of efficiency or 9/11 security concerns? Commodore Vanderbilt probably never thought his ferries would be carrying horseless carriages; he (as once explained to me by one of his descendents) started his fortune by hauling manure from Staten Island in a rowboat.

Nevertheless, the ferry fare had been cheap. The Verazzano Bridge is enormously expensive: $9.50. And you had better have a EZ pass, because you will never make it across the Verazzano toll plaza to the two lonely cash booths. Fortunately they were on the same side of the toll plaza as our Bay Street exit.

There is indeed another, quicker non-Bay Street way to get to Snug Harbor, but it involves mysterious turn-offs and the ever-present threat of ending up in New Jersey, where the Meadowlands presents a no-man's-land automobile vortex. Or at least that's how it appears to Manhattanites. Staten Island is in New York City, isn't it? It is treated so badly by New York City government agencies that you sometimes wonder. It is the pot-hole capital of the world, and there is the slight problem of the Fresh Kills dump.

Sylvia was wide awake, and having adjusted her hearing aid, was again holding forth, as was Arlene. As was Nancy.

Silence, I demanded. If, as navigator, I can't concentrate, we'll end up in New Jersey!

Our route around the tip of S. I. on Bay Street was foolproof, but unfortunately presented a grim picture of the island that, artwise, used to be mine. We did not traverse the Green Belt, nor did we even glimpse Lighthouse Hill (where the Jacque Marché Museum of Tibetan Art perches just up the street from a Frank Lloyd Wright Usonian abode. Or mysterious Todt Hill, with its rock-star mansions and spectacular Cinemascope views of New York Harbor.

We did see the sign for the Alice Austin House. Since the Snug Harbor galleries would be closing in an hour and a half, we didn't have time for this charming, shoreline house museum. Alice Austin House is named in honor of a pioneer woman photographer, and, if we are to believe some of her snapshots,habitual instigator of rampant, larky cross-dressing on the part of her many women friends. After all, opined Raven, the two serious ladies of Jane Bowles' novel of that same name lived in Staten Island, didn't they?

But I did point out a sealed 1920s movie theater, no doubt now a live-mold and harbor-rat museum; and a charming park once popularly known as St. George's very own Needle Park. And then the odd-looking Yankee's ballpark. The Yankees! shouted Grossman.

According to Sleigh, painter Craig Manister (co-curator with painter Cynthia Mailman) suggested that everyone should enter through the front door of the Main Hall (Building C) at Snug Harbor. The cornerstone was laid in 1831, opened to the Snugs and staff in 1833. And so, according to some, was inaugurated the first nonreligious charitable institution in the U.S.

I guessed Manister wanted everyone to see the Main Hall. I myself know it by heart. I had my office there; that office was once Thomas Melville's when he was president of Sailors' Snug Harbor from1867 to1884. And now it is a gift shop. Oh, the indignity of it: not one of my great-great literary uncle Herman's books for sale! Not one of his great-great nephew's exhibition catalogs. And none of his recent seascapes, either.

Everything in the 1831 Main Hall is cleaned up now. No peeling paint. But tears came to my eyes when I saw the marble mantle in my old office. I could look out on the founder's obelisk, really a grave marker, for he is buried beneath it, apparently standing up: Captain Robert Richard Randall; c. 1750-d. 1801.

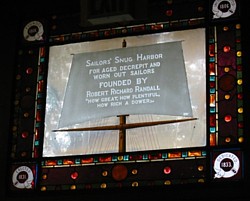

I could still hear the honorific toots from passing freighters and tugboats in the Kill Van Kull just across Richmond Terrace, running between Staten Island and Bayonne. Sailors' Snug Harbor was founded and maintained for the benefit of "aged decrepit and worn out sailors" as the stained glass window over the entrance says. The inscription is read from the inside, by the way, no doubt to remind the Harbor's indigent charges of Randall's or perhaps the Trustees' magnificent beneficence: three square meals, and two seamen to a room. Alcohol forbidden.

In this century, the institution was called to task by city health officials for the Harbor menus; the city had to withdraw when it was shown that retired seamen hated salads and raw vegetables and routinely dumped them under the table.

I have seen a reprint of a list of "taboos." This was Captain Tom Melville's term, no doubt borrowed from his brother Herman, who was famous for his fictionalized adventures in the Marquesas in a book called Typee. Furthermore, if you came back drunk from the off-grounds saloon, you would be "tabooed" and confined to your room for several days.

All "aged decrepit and warn-out sailors" were accepted. Even some blacks. Eventually the Harbor also allowed steamboat sailors and inland sailors from lakes and rivers too, but they were no doubt frowned upon as not being adventurous enough. Once, while trying to affix a sculpture to one of the walls, we found a sealed-offcompartment containing a book of photographs of hundreds of inmates (as the retired seamen were called). Here and there were some dark faces. All races and nationalities were welcomed. Only "habitual alcoholics and those with contagious disease or immoral character were banned." Does the latter mean those who have sex with other men?

The Main Hall, a prime example of Greek Revival architecture,is now a visitor's center and currently also showcases some artworks from the S.I. Institute of Art (which will eventually open additional quarters in Building A and B.) Look at the dome above. Note the nautical decorations and inscriptions and stained glass over the doorways. There's a beautiful crescent moon. But I know a secret.

Behind the sunburst at the front of the dome is a small room lined with tin and a movable mirror with which one can redirect the light from the skylight so that it blazes through the painted glass sunburst. The attic is in fact quite wonderful, for there, if you are luck enough to get a tour, you can see the shipbuilding joinery used to interlock the timber and quaint sailors' graffiti scratched into the gigantic beams. We had trees then.When there was old forest left it was said that a squirrel could travel from the shores of New England to the Mississippi without ever touching the ground. And the stoneon the fronts of the buildings was floated down the Hudson from Sing-Sing quarry.

When I was there, the Main Hall was for showing art. Some of the installations I engineered were gigantic -- a survey of the welded sculpture of Ann Sperry; hanging stones by Gillian Jagger; and a three-story wave of saplings by Patrick Dougherty that looped from the upper railings down to the floor.

* * *

Sleigh on Display

Now the Newhouse Center for Contemporary Art is confined to the building behind the Main Hall, where the dining rooms were. There our merry group contemplated Sleigh's show "Portraits and Group Portraits" (through October 2). What would the old sailors have thought of all those male and female nudes? The males sometimes unashamedly frontal? Even today it was necessary to warn the public that two rooms have nudes displayed.

Or what would the sailors make of the fully clothed gang of women artists who make up A.I.R. Group Portrait (1988)? What are all these women doing together, besides staring us down? This is probably Sleigh's best painting. A.I.R. is a pioneering women's gallery, and she captures all the energy of that feisty, talented group. It complements or contrasts with The Situation Group (1961), a painting Sleigh did of the mostly male British Pop group -- which included Alloway, her husband, who coined the term Pop Art.

Sleigh liked the way her paintings look against the warm white of the rooms. I was there when the Snug Harbor resident architect chose it: Benjamin Moore Antique White. So much better than MOMA stark white, says Sleigh. But I think her paintings might have looked even better in the Main Hall: her patterned backgrounds wilder against the Victorian moldings and the ornate nautical décor.

Arlene Raven's catalog proem, "In the Details; Sunday with Sylvia," outlines how it felt to be painted, hyperactive Nancy hovering over her, while slumped in reverie. Most relevant here, however, is the quote from Sleigh:

"Even if I paint a leaf, it should be a portrait. If we could all appreciate every living thing in detail, we would be kinder and better to one another. "

I've been painted many times by Sleigh -- once famously in the buff, added to a room of other naked art critics -- but not in the current sampling. Here there's a picnic painting that treats me kindly, as does a preliminary drawing for her Invitation to the Voyage, which I once showed in the Snug Harbor Main Hall as part of an exhibition I called "Eminent Immigrants" in 1986.

* * *

Ghosts I Have Known

1. Building ghosts:

The Snug Harbor Cathedral, caught mid-wrecking-ball in a photograph in the Staten Island Advance; the panopticon Sung Harbor Hospital. On foggy nights, they reappear.

2. Ghosts of ships:

Thomas Randall's pirate ships: Charming Sally and Le Jeune Babe. If I had a boat, even just to cross the Great South Bay from Bellport to Ho-Hum Beach on Fire Island, I'd name it the latter, wouldn't you? And if you could use male names for vessels, I'd name it Captain Randall.

3.More ghosts of exhibitions past:

David Finn's masked, garbage figures in the C-E Hyphen. Judy Chicago's "Birth Project"; Beth Swartz's "Moving Point of Balance." "The Sculpture of Elizabeth Egbert " (indoors and outdoors)....Currently art spaces and museums can barely produce one exhibition every six months, I installed one every month. But that was the '80s.

4. Imaginary ghosts:

The front buildings are connected to each other and to the building in the back row by architectural "hyphens" or first-floor enclosed passageways so, I suppose, the "inmates" would not have to deal with the elements. In the basement of the building behind Main Hall, right where it connects to theC to E hyphen, there is a ghost: a priest clubbed to death by an angry sailor.

5. And yet another ghost:

When I was on board at Snug Harbor, the Matron's House (directly behind the showplace buildings) was used for artist studios, and several of my friends reported hearing footsteps. My assistant Charlie, who had a studio in another building,saw a woman in Victorian clothes looking out a window on the second floor of the Matron's House. Legend had it that her illegitimate child had been still-born and she had never recovered, even after death, from this tragedy.

6. Mad ghosts and dream ghosts:

Even the still-living can generate ghosts, as can the never-having-really-lived.

Artist Jane Greengold, under my reign, had turned one of the Main Hall rooms into a replica of a sailor's bedroom and then depicted that sailor's dream in another room in the cellar of the D Building next door. If you peeked through the window, you could see chaos and depictions of rushing seawater. We suspected that the mad guard, a frustrated artist, had taken a match to the painted waves. There was no proof and it was for threatening behavior that he was carted away in a straight-jacket, leaving behind his forever angry ghost.

And there is also the ghost of Greengold's fictional sailor, so vividly brought to life by "his" bedroom and "his" dream.

7. Richard Randall's ghosts:

Of course, bachelor Randall, son of an infamous privateer (i.e. legally sanctioned pirate) left several ghosts behind. The legend is that Alexander Hamilton, a friend, announces that " it came from the sea, so let it go back to the sea." What came from the sea was Randall's family fortune. Seamen then had no social security or retirement accounts, so Richard on his deathbed wanted to step in.

Randall was long gone when Snug Harbor finally opened on Staten Island; but his corpse was moved from Trinity Church cemetery to soil he had never walked on. Local legend has it that he walks at night, trying to get back to Manhattan. Does his ghost know there's nothing but apartment houses and a K-mart where he once lived in an octagonal building on his 21 acre Minto farm? It was the subdivisions of that farm that provided the money for Sailors' Snug Harbor.

Then too the present bronze statue of Randall, now surrounded by garish Victorian plantings, is only a replica of the one made by Augustus Saint Gaudens in 1878. Where is the original? Sailors' Snug supposedly took it down to Sea Level N.C. when they moved after New York city bought all 80 acres and the surviving 24 buildings in 1978. But is it still there? The statue, overlooking the Kill Van Kull, is a bronze ghost. Art works too can leave ghosts behind.

I am sure Randall has several other ghostly manifestations haunting the descendents of the various trustees of Randall's, who profiteered upon his estate.In Manhattan it stretched from what is nowWaverly Place to 10th Street and from Fifth Avenue to Fourth Avenue. Look at your Lower Manhattan map. Not exactly what you would call cheap land. Well-placed politically and with Albany links, the Randall trustees -- you know who you are, you long-dead mayors and ministers, you creeps -- kept changing the rules as the city marched north, until Staten Island became the solution. Put the sailors there, and let's get on with filling in the Manhattan grid. And then there is the expatriate Tory, John Ingles, the Bishop of Nova Scotia, who contested Randall's will from abroad to make some point or another about Tory rights. Or for cash.

8. Entertaining ghosts:

Snug Harbor, now more correctly called Snug Harbor Cultural Center, is full of ghosts. There are the ghosts of all the performers that entertained the sailors in the Music Hall. Did the notorious actor Edwin Forrest play there? He who was once described as "as a vast animal bewildered by a grain of genius"? Did Edwin Booth? Did the operatic Jenny Lind? And I'd like to know too what movies were shown to the sailors, beginning in 1911? And now there's probably a ghost of the three-inch thick mold I saw covering all the seats of this once gas-lit theater when it was unsealed for restoration. There were also individual earphones in the vast Library/Recreation Hall, so that Snugs could listen to broadcasts undisturbed. Does the music from those broadcasts linger? And are there ghosts of the Stickley chairs and desks, stolen between regimes, long gone?

9. My ghosts:

And I have added some ghosts of my own. A living person can have a ghost. I am in that old front office of mine, selling souvenirs, writing poems between each transaction. But above all I am in the concealed tin room high above in the dome, moving the mirror.

* * *

Recommended:

Barnett Shepherd, Sailors' Snug Harbor: 1801-1976, Snug Harbor, 1979.

(Shepherd proves that the Main Hall architect was Minard Lefever, famous for his Greek Revival pattern books: The Modern Builder's Guide and The Beauties of Modern Architecture.)

Gerald J. Barry, The Sailors' Snug Harbor, A History, 1801-2001, Fordham Press, 2000.

(Barry reveals that Thomas Melville, although investigated and called to the carpet for his irregular purchasing policies, was never actually prosecuted for embezzlement.)

-

AJ Ads

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Exploring Orchestras w/ Henry Fogel

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary

Tyler Green's modern & contemporary art blog