main: June 2004 Archives

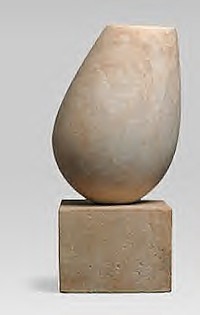

Brancusi: Torso of a Young Girl, 1922

Brandcusi

How much is enough? How much too little? By all accounts, Constantin Brancusi (1876-1957), soon to be repackaged as a protominimalist, did not produce much art compared to, let's say, Picasso. Thirty-five Brancusi sculptures are now at the Guggenheim under the title "Constantin Brancusi: The Essence of Things" (1071 Fifth Ave. at 89th St., through Sept. 19).

On the grounds that an artist is the sum of everything that has been written about him or her and not just the latest blip on the curatorial screen, I turned to my library to reach into the not-so-distant past. Sydney Geist, in his 1975 Abrams book Brancusi: The Sculpture and Drawings, listed 215 works of sculpture, but admits that he "omits those objects made by the sculptor which the author does not think to be sculpture." He counts the horrible academic sculptures of Brancusi's youth; he also counts a few plaster models.

Years later, we are spared these at the Guggenheim, so that rather than the "essence of things" (whatever on earth that means), we are given the essence of Brancusi.

Weirdly enough, Geist included as sculpture the stools and tables of Table of Silence for the Tirgu Jui public park in Brancusi's native Romania, but not the wonderful 1917 oak bench now in the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Did this mean in 1975 that seating could be sculpture if it was of stone and public, whereas private seating made of woodcould not? If sculptor Scott Burton had read Geist's book, it would probably have driven him crazy. Burton's art is proof that, regardless of context or material, furniture can also be sculpture.

Nevertheless, it is safe to say that Brancusi made only about 200 sculptures, give or take a few benches, and many of those sculptures were reworkings (not necessarily refinements) of but a half-dozen serious, serial themes: kissing lovers, sleeping heads, birds, fish, and "the endless column." Picasso, as we know, produced thousands of artworks. I choose Picasso because Brancusi had as big an impact on sculpture as Picasso did on painting.

Perhaps comparing sculptors to painters is not fair. Sculpture used to take more time. To make matters more difficult for himself, Brancusi, that Romanian "peasant," decided that the way Rodin did things (young Constantin had worked in the master's studio) was all wrong. The standard way of making sculpture was to produce a model in clay and then hand it over to artisans who chipped it out of stone. Brancusi, according to Isamu Noguchi (who, in turn, had worked in Brancusi's studio), disparagingly referred to clay as beefsteak. No, the best way to make sculpture was to do the carving yourself. Noguchi came back to that at the end, but only when everyone else, with the advent of minimalism in the '60s, had moved ahead -- or back -- to the factory-made.

Few minimalists I know of would have touched the actual materials of their art. Well, I take it back; Robert Morris actually sawed the plywood for his early, severely geometric sculptures. When you are poor you do what you have to do, but the ideal sculpture tool became the telephone. Phone the factory with your instructions; have the sculptures shipped to your gallery or directly to some museum or other. Although I never, never would refer to clay as beefsteak (and rather enjoy hands-on making myself), I still think there is nothing wrong with telephone art -- although once you know how Rodin made his sculptures, hands-off execution does seem rather 19th-century. I am fond of saying that you should be able to make a sculpture or a painting as fast as you can take a photograph.

There. Now you see how easy it is to write art criticism. I have established Brancusi's importance, noted that some referred to him as a peasant, and linked this essay to my last two (on Noguchi) and my cycle of mini-essays on photography.

Let me flesh out some points:

The Progress of Sculpture

Once upon a time, the sculpture legacy seemed to go from Rodin to Brancusi to Noguchi. As I have already indicated, Brancusi worked in Rodin's studio; Noguchi worked in Brancusi's. Since these connections were brief indeed, making much of them is equivalent to saying that I am the heir to Duchamp because I once saw him get out of a taxi on 12th Street. Or that I am Clement Greenberg's son because I once served on an art jury with him and was party to hiding his bottle of scotch.

But the meaning is more important than the truth. Figurative apprenticeships notwithstanding, what we are getting is a grand march to abstraction. The new view, whether Noguchi is included or not (probably not), is that Brancusi leads to Donald Judd. After all, Brancusi did once say about his art that, "The observer knows what is there at a glance." The Guggenheim itself -- though we thought it had pretty much lost its position as an arbiter of taste and art history -- points to this direction by way of "Mondrian to Ryman: The Abstract Impulse" on the upper ramps, supposedly there to give some context to the Brancusi offering.

Making minimalism, rather than Jules Olitski's Color Field painting, the end point of modernism allows us several advantages, not the least of which is that we might not need postmodernism ... or pluralism.

First of all, almost everyone but Clement Greenberg could see minimalism as an extension of modern art in its march-to-total-abstraction mode. Yet Greenberg thought Barnett Newman and Ad Reinhardt were bad enough and had gone too far already. His disciple Michael Fried thought minimalism wasn't art, but theater.

Secondly, neatness counts. In fact, neatness counts so much that many would be willing to sacrifice Pop, Photo-Realism, and Judy Chicago -- and probably even Feminist Art and Body Art, never mind conceptualism, if art could have a coherent history again, a story worth telling.

Finally, from an institutional point of view, as long as minimalism was excluded from modernism, there was a need for postmodernism and pluralism too. Could it be that no one noticed that collectors had long since stopped listening to Clem, that no one noticed he had passed on to bully heaven or bully hell?

Presentation

But before we get to the hard part, I should say that the current Brancusi survey is a nearly perfect introduction to the evolution of abstract art (if you still need such) as well as the perfect installation of an exhibition in the difficult Guggenheim space. No matter how spectacular the atriumlike rotunda, we are still stuck with Frank Lloyd Wright's perverse notion of how to display art: in little, tilted-floor alcoves. Here, the Brancusi sculptures are allowed to stand up to the alcoves. Less really is more. There are never more than two or three to an alcove and, frankly, they need that kind of space. You have to walk around them!

And you can. Since he apparently had no use for other people's art, Mr. Wright is probably rolling in his grave. For once, the sculpture outclasses the building.

If you take the half-circle elevator to the fourth level and walk down, you'll get a succinct survey of Brancusi's journey from The Kiss to the great bird sculptures. He does indeed get more and more abstract (but never, never totally so), and the pedestals grow in importance.

Surely, after the 1989 Burton-organized MoMA exhibition of Brancusi's pedestals ("Artist's Choice: Burton on Brancusi"), we cannot look at them in the same way. They too are sculpture. Beginning midway down the ramp, imagine the sculptures on other pedestals, standard or fanciful, and you will immediately understand that the pedestals had became integral. Late in life, Brancusi labored on them more and more, and at the risk of seeing every one of his artworks as a column of sorts, it is illuminating to see the pedestals as not separate from the carving or bronze at the top. His sculpture became a higher form of stacking.

As someone who once got an A+ for some very mediocre drawings simply because he had the good sense to present them nicely matted, I know how much presentation determines the way we see art. Brancusi understood this before anyone else; well, nearly before everyone else, for we should not forget that his pal and, later, American sales representative Duchamp demonstrated that mounting a bicycle wheel on a stool turned it into art. Whether influenced by Duchamp or not, Brancusi obviously wanted to control how his carvings were displayed by insisting that the pedestals were also the work. This is equivalent to a painter insisting that the frame is part of the art.

What people do with your art once they buy it is a constant problem. If your art is a small sculpture, it will end up on a bookshelf or coffee table. If it's a small painting, it will end up in the hall or in some decorator arrangement with a number of other small paintings and drawings, prints, photographs. Help!

Make it big. Make it too big. Only then will it stand up to the clutter.

The Master Plan

Since it was Mr. Wright's idea to show art on a spiral ramp, one can deduce that he of all people was linear to a fault. He believed in a master narrative. That all art history obviously led up to Frank Lloyd Wright should go without saying, right?

The Guggenheim ramp therefore is the perfect vehicle for the notion of progress, from figuration to semiabstraction and on to total abstraction. Remember that the Guggenheim was originally The Guggenheim Museum of Non-Objective Art.

Yet Brancusi never stepped off the cliff. All of his sculptures, even the succinct series of heads that culminates with Sculpture for the Blind, are still grounded in representation. But he was getting there, which is one reason he was always considered so important to the working out of the master narrative of modernism.

Now he is embraced as a predecessor of minimalism, which, with the evidence before us, at first glance seems odd indeed. Minimalism is never whimsical, as some of Brancusi's lesser efforts are (here see the revolting King of Kings or elsewhere, his Penguins ). Also, everywhere we see evidence of Brancusi's hand, even in the shiny, shiny bronzes. All were finished by hand because he knew no machine could get the perfection he required. Minimalism, however, is about the artist's choices, not the artist's touch.

Pluralism and Pop Art, emerging in the '60s, destroyed the modernist narrative, which, as any such master narratives tend to do, had became prescriptive rather than descriptive. Oh, how we loved that master narrative!

Although Brancusi sculptures are wonderful indeed, some part of the unexpected emotion they now engender has to do with their place in a narrative now lost. Although stories can be used towards wicked ends, we still need them as temporary maps. Now that postmodernism is over, perhaps better storiesmay be told, such as ...

Brancusi and Sex: The Untold Tale?

Brancusi can fit in a new history of art that concentrates on gender and sex. Although the gross Princess X of 1915, supposedly a portrait of a young woman, is breathtakingly phallic, the elegant Torso of a Young Man (in all its versions) paradoxically has no visible maleness. Has the divine, alchemical hermaphrodite made its way into Brancusi's self-proclaimed art of essences? Or was Brancusi, who never married and lived alone, trying to tell us something about his own bent?

I love using artist quotes and quips, particularly when they have been cited over and over and become true -- true insofar as they determine how the artist is seen or, rather, heard. They are often like Zen koans or the sayings of a Taoist sage. What did Jackson Pollock really mean when he said, "I am nature"? What did Brancusi mean when he said, "Nude men in sculpture are not as beautiful as toads"?

A quote has to be quotable, as it were. I am certain that the quote people will pull out of this very essay will be: you should be able to make a sculpture or a painting as fast as you can take a photograph.

Brancusi thought he was competing with Michelangelo and the monumental tradition of sculpture, not with Rodin, and certainly not with photography. This is why he said, "Michelangelo is too strong. His moi overshadows everything." How useful is that moi! One could also say that Picasso's or Gertrude Stein's or Martha Graham's moi overshadows everything. And today? Alas, there seems not to be any contemporary artist, writer, or dancer who has a moi big enough to overshadow anything taller than a thousand dollar bill.

On the other hand, it may have been the idealized masculine body that overwhelmed gentle Brancusi, best friend of Modigliani and Erik Satie. "Who would imagine having a Michelangelo in his bedroom," quipped Brancusi, "having to get undressed in front of it?"

Or: The Court Case That Invented Brandcusi and Saved Abstract Art

Brancusi can also fit into a new history of art told in terms of art law. Abstraction is now such an important part of art that we may forget there was a certain struggle involved. Brancusi became Brandcusi because, through no fault of his own, he profited from that struggle.

As recounted by David Lewis (Brancusi, 1957, Alec Tiranti, London), in 1926 a shipment of Brancusi sculptures was held up by U.S. Customs, which regarded them not as "works of art, which may enter free of duty, but as manufactured implements, and stamped them 'block matter, subject to tax,' the tax being 40%." Edward Steichen had to pay $240 tax onthe $600 Bird in Space. Brancusi contested, and the rest is history. Or used to be history.

"Would you recognize it as a bird if you saw it in a forest,' asked Justice Byron S. Waite, "and take a shot at it?"

"Could not any good mechanic," demanded First Assistant Attorney-General Marcus Higginbotham, "do just as well with a brass pipe?"

"Surely if he could, testified Jacob Epstein," who appeared for Brancusi, "as soon as he does, he becomes an artist." But the best is yet to come. Brancusi won, and for a number of years nonrepresentational sculpture was allowed to enter the U.S. without import duty, providing the works had "representational titles."

Conclusion: The Secret of Brancusi's Success

Committed bachelor Brancusi was a great cook. He may have called clay "beefsteak," but he had a way with meat:

The man, now well over 70, living alone, as he has always lived, in his studio has now become famous for his broiled steaks cooked by himself at his own fire which he himself serves as though he were a shepherd at night on one of his native hillsides under the stars. A white collie named Poliare used to be his constant companion, reinforcing the impression of a shepherd which, with his shaggy head of hair, broad shoulders and habitual reserve, he seemed to his friends to be.

-- poet William Carlos Williams, quoted by David Lewis.

* * *

Was Brancusi a peasant, a primitive like his pal Henri Rousseau? Did he really walk from Romania to Paris on bare and bloody feet? I know this: modern art would not be the same without him. Some of his work may now look cloyingly sentimental, but what to this day can match The Birth of the World/ Sculpture for the Blind or his Bird in Space?

I despise his talk of essences. And thanks to sculptor Athena Spear's Brancusi's Birds, found in my library, we now know that his commitment to the truth-to-materials doctrine of doctrinaire modernism was more in word than deed:

Brancusi never exploited the elasticity and structural strength of bronze. Another example of his untruthfulness to the nature of the material is his disregard for the very limited elasticity of marble in the case of the Bird in Space; as a result, half of his marble birds are broken at the waist in spite of the metal rod inserted in them.

Here, we really have to ask, what does truth-to-materials actually mean? Would we be more correct if we thought of modernism as a useful myth, offering guidelines rather than chains? Did postmodernism really set us free? And now that it's over, what new burden can we assume? Is taste the enemy?

Brancusi began as a legend, and he ended as one. According to David Lewis, he "requested to be buried naked, directly in the earth but the French officials would not allow this, considering his request to be in bad taste."

Isamu Noguchi: Interior Courtyard, Noguchi Musuem

I took the press-preview bus to the newly renovated Noguchi Museum in Queens (32-37 Vernon Boulevard, Long Island City), and this is my report. If you haven't read last week's little essay, please scroll down and read it now, because it sets up the themes that will now prevail: restoration, memory and presentation. Note too that the photo above took me hours to choose. Is it too glamorous? Not glamorous enough? Should I have used a close-up of one of the sculptures indoors? A cluster of lamps? Should I have tried even harder to make Robert Wilson's installation on the second floor look decent?

In terms of these art trips, you are trapped with other art writers, faux-press, collectors, educators, and always perky information officers. Nevertheless, since I remembered how difficult it is to get to the Noguchi Museum on one's own steam, I sacrificed my anonymity. What's a stick-on name tag among friends? At least they spelled my name right, and I wouldn't have to spring for a cab.

I try not to drive in New York, particularly during times of high-volume traffic, and my slight knee-injury from my photo-accident in Philadelphia (I slipped on ice while photographing industrial ruins, if you remember) precluded the ten block walk from the subway stop nearest to the Noguchi -- ten long Queens blocks, not manageable Manhattan blocks.

After being closed for two and a half years for sorely needed renovations, the Noguchi Museum was reopening. The brick, 1928 photo-engraving plant with the artist's 1982 cement-block addition is so close to the bank of the East River that the basement was always full of river water. Uck. Built on landfill over water, the walls were settling and cracking. Everything is now shored up, as it were, and there's even heat and air-conditioning for the fully enclosed galleries, so for the first time the museum can be open all year round.

The museum is restored to the way Isamu Noguchi (1904-1988) made it, wanted it, left it behind. The first floor with its partially open-air, cement block "rooms" and a cozy garden feature his mostly clunky, I think, late sculptures. Nevertheless, there's joy in seeing his mind at work in their deployment in space. Noguchi worked as Brancusi's studio assistant in 1927, but here, aside from one glorious marble hoop (called The Sun at Noon, 1969) not much of Brancusi's sublime reductiveness seems to have stuck.

Noguchi is an interesting case study. Born to an American mother and a Japanese father, he was rejected by his professor dad when he and his mother moved to Japan. Later, back in the U.S.A., when his mother dumped him at the age of fourteen at the Interlaken School in La Porte, Indiana, he was known as Sam Gilmour, using his mother's surname. In early adulthood, he studied "academic sculpture" at the Leonardo de Vinci School of Art on Avenue A in New York. His teacher, one Onorio Ruotolo, afterwards claimed he had taught Noguchi by psychic means. Another teacher, Gutzon Borglum of Mount Rushmore fame, thought he had no talent at all. On his way to Japan, Noguchi, who now had taken his father's name, crossed the Soviet Union in search of Vladimir Tatlin's Monument to the Third International, unaware that it had never been built. Mistakes, mistakes. During the Second World War, he made the mistake of allowing himself to be convinced that he could do good work as a Japanese-American by voluntarily admitting himself to an internment camp in Arizona.

Most interesting of all - even more interesting than Noguchi's liberal/left politics - was that as former director of the Noguchi Foundation Bruce Altshuller says in his excellent 1994 Abbeville book on the artist (the source of all the above "color"), Noguchi was considered too American by the Japanese, who found his ceramics unnaturally beholden to Japanese traditions, and too Japanese by the Americans whose attitudes could be blatantly racist. As an example of the latter, I offer the following from the Altshuller book:

The prominent New York Sun critic Henry McBride chose to focus his review on the 1933-34 public projects...These designs were snidely described by McBride as "wily" attempts by a "semi-oriental" to manipulate American sentiments, the consequence of Noguchi's studying our weakness with a view of becoming irresistible to us." McBride picked out one other sculpture for racist complaint - a close-to-full-size Monel-metal figure of a lynched black man. This he called "just a little Japanese mistake."

And I always thought McBride, an early support of modernism, was one of the good guys!

But am I in the minority? I revere Noguchi's design work. And, when I see more this fall when "Noguchi and Graham" opens at the museum, I will probably vote a great big Yes for his "sets," props, and costumes for dance-matriarch Martha Graham, although we curse the day she read Carl Jung and apparently simultaneously discovered that dancers could move centered on their solar plexus - somewhere around the belly-button -- and thereby writhe expressionistically on the floor, as if every emotion was like giving birth, difficult birth.

On the basis of the Noguchi Museum garden and his plantings at Lever House - - cleverly the departure point for our tour bus - I suspect Noguchi was a fairly good landscape designer. His public sculpture, like the late stone carvings, remains iffy.

I do like his stainless steel Wall for 666 Fifth Avenue (1956-58) and I

remember ages ago how delighted I was when I worked nearby (at the ancient Brentano's Bookstore, as foreign magazine subscriptions manager and noontime rare book clerk) and discovered that the art I admired was actually by Noguchi. Is it still there? I'll have to check next week.

I never liked his 1968 Red Cube balanced on one point in front of the Marine Midland Bank Building but admired his Zen-influenced Sunken Garden for Chase Manhattan Plaza, 1961-64, also all the way downtown. I wonder if after 9/11 both are still there. So I must make a note to myself to take a look next time I go to Century 21 for discount designer clothes or to J&R for camera or computer stuff.

On the debit side, is dreadful 1984 Bolt of Lightning...Memorial to Ben Franklin that greets you as you drive across the Benjamin Franklin Bridge into Philadelphia. In a city with the worst public art in the universe - next to Chicago -- this travesty wins the prize for sculpture as unintentional parody of "modern" art. To this day I can hardly believe that Noguchi, who designed such splendid tables and paper lamps could have had a hand in this wacky, ugly homage to Franklin's kite experiment.

But back to the present. The first bit of good news is that although Noguchi did not envision such, in November there will be a room at the Noguchi Museum devoted solely to his design masterpieces. The other good news is that there will be at least one temporary exhibit annually on Noguchi qua other artists or on art that influenced him or was influenced by him, thus expanding the museum's mission and making repeat visits a necessity.

Sadly, the announced exhibits, with the exception of "The Imagery of Chess Revisited" (a recreation of the famous 1944 chess show at the Julien Levy Gallery, are not exactly breathtaking. To include the banal Andy Goldsworthy in "Noguchi: Sources and Influences," coming in October 2006, has to be a typo. I would urge a Scott Burton survey. I would urge an exhibition of lamps by other designers and sculptors. I would even like to see a show of Robert Wilson's opera sets and furniture.

The bad news, alas, is that the first temporary exhibit "Isamu Noguchi: Sculptural Design," out of the Vitra Design Museum in Germany, is muddled. I say see it at all costs - because of the great Noguchi furniture and lamps -- but be aware that, contrary to what you might have heard, the just afore-mentioned theater "genius" Robert Wilson might not be at his peak when designing exhibitions: this effort is stygian and chaotic. It is so dark, take a flashlight with you. Noguchi works, good and bad, are picked out with pin-spots in a series of disorienting caves.

Because I was offended by the very idea that major museums would fall for an Giorgio Armani retrospective, I did not see Mr. Wilson's efforts either at the Guggenheim in New York or at the Walter Gropius-designed National Museum when I was in Berlin. Surely there are clothing designers who are artists on the level of painters and sculptors - Rei Kawakubo immediately comes to mind - but Armani for all his good taste is not one of them. To put it simply, he had the funding in hand.

Here at the Noguchi: stop the Musak; let in the light. Wilson's opera designs may be great, but what works at a distance does not necessarily work up close. The Noguchi Museum's new gift shop looks better and better honors Noguchi's famous sofa than does Wilson's murky tableau, using a fake window and wood-chips. And that winding path over large-gauge gravel, makes Noguchi's little bits of sculpture seem like counters in a game of Parcheesi or Snakes and Ladders.

* * *

The inaugural survey exhibition aside, single-artist museums like the Noguchi, designed by the artists themselves, may be the ideal way to see a body or work - or not, depending on the artist. By all reports, Donald Judd's museum in Marfa seems to be transcendent, which is an ironic term for the work of a minimalist whose thoughts on art approach Logical Positivism.

I salute the sensitive, almost willfully nonglamorous restoration/renovation of the Noguchi Museum and would hope for more artist-focused (and artist-financed) self-memorials but I have to mention that just because you are a great artist doesn't mean you are a great curator of your own work. How many artists really know what work is their best? It is like choosing your favorite child. And do all artists know how best to display their wares? Noguchi obviously knew how to present his sculptures in their best light. As in a really good photograph of ultimately dull work, they probably look better in Queens than they could look anywhere else. But isn't how they photograph and how they are remembered what they are? There's a full-scale Noguchi sculpture retrospective coming to the Whitney next October so perhaps I will be better able to appraise his work. I know I like the photographs and my memories of notched, marble slab, bio-morphic pieces from the '40s, YvesTanguy be damned. But all the rest?

Exterior Noguchi Museum (Detail), 2004. Photo: J.Perreault

I prefer to take my own pictures. It helps me get closer to (or further away from) the art. Sometimes with my digital I take dozens of images, more than I can use and more than necessary to cover the shot. Is this a way of making notes? The camera accomplishes several other things. The man with a camera is off-bounds, thus ensuring both visibility (you don't want to bump into the photographer) and privacy (you don't want to talk to him or her). There is also the fear that the camera will turn on you, thus interfering with your own invisibility and privacy in public.

I was at the press preview for the renovated Noguchi Museum in Queens, so no one stopped me from taking pictures. Usually you cannot take photographs in museums and galleries, even if you are an art critic.

Is it a matter of copyright? Flash-damage? Annoyance to other viewers? Not using a flash would solve the latter. It's really about image control, which is close to eye control, and therefore mind control. Museums and galleries want you to see the art in a certain, carefully designed way.

Proof of this is that press photos are sometimes very deceptive; artists, galleries and museums pay big money for glamorous photographs. Now, it is true that I too intend to take glamorous photographs of art. If I am writing about something, it usually means I like it and I want it to look as good as possible. I want the photograph to convey my affection or attention.

The situation here in ARTOPIA is unusual; I choose the picture. Thanks to the little darkroom in my computer, I can even crop it myself, improve the focus, et al. In print media, the critic usually does not select the photographic illustration, never mind actually take it himself. He may pass along whatever photo handouts are provided, but the editor decides. Some newspapers eschew the handouts and send their own photographers, probably because they do not want to be beholden to the source or because they do not want to run the same publicity photographs as everyone else. When I was at the Village Voice, the staff photographer for some reason had total control and my columns were usually accompanied by photographs of works I had not even mentioned. Worse, although he was good at documenting "the scene," he had bad taste and tended to photograph the artists themselves peeking through or from behind their sculptures, a form he favored.

The truth is that even when I am allowed to use my camera, I may never use the images. I ruthlessly delete. But at least I will have had the experience of seeing the difference between what the object looks like, warts and all, as opposed to what it looks like in the rectangle of my camera, flat and wartless.

The things left out of the picture, or are heard but not seen, are often more important than what the rectangle holds. This is why we still need words, which, although they do impose their own kind of rectangles, have a certain flexibility, generosity, vividness.

For instance, when I was in Berlin last year for an exhibition of my art, I had a chance to run around some spectacular museums. As long as you don't use a flash, you seem to be allowed to take photographs. I had a field day. But friends asked: why did you take a photograph of the scaffolding and not of the Pergamon Altar itself? The Pergamon Altar is a Hellenistic masterpiece housed in the Pergamon Museum on Museum Island in Berlin (in what formerly was East Berlin) at the end of the famous boulevard called Unter den Linden. Ah, to walk along Unter den Linden in the footsteps of E.T.A. Hoffmann or Walter Benjamin. The Brandenburg Gate is at the other end. When I returned to New York, I actually rented Billy Wilder's super-silly One, Two, Three to see how the German Democratic Republic looked before the wall fell. Except for the Brandenburg Gate, there wasn't much to see. But I noted that unlike now, there was no Starbucks just beyond the ceremonial arch. (I have a photo of a Starbucks window reflecting the Brandenburg Gate, just to prove one is there).

The Pergamon Altar is enormous, with a huge tier of marble steps that makes it look bigger than the building it's in -- which no photograph can convey. Of course, that very week they closed for repairs because the skylight was in danger of falling in. I got in just under the wire, but I suppose, camera in hand, I could have been killed, leaving behind a digital image of glass shards, blood and rubble on marble. Fixed up, the Pergamon is open again.

I read today that the Guggenheim, the flagshipin New York (not the mingy little room in Berlin on Unter den Linden) is set for a major overhaul too. It is about time. Peeling paint and rust stains do not make a good impression. I don't think the skylight is in danger is falling in, but presentation is all.

When subjected to my Berlin photos, my friends kept asking the reason for all the shots ofchip-board. And the grass growing between the cracks of the pavement in the courtyard of the Bauhaus Archive? Why that neatly piled caterers' cube of folding chairs under a form-fitted red wrap?

My answer: If you can buy a postcard of the Pergamon Altar, why not photograph the people looking at it instead, using the altar as an excuse? Or the pile of chip-board stacked like minimalist sculptures, or the Judd-like chipboard doorway-protectors? Signs of life are more important than postcard views.

Oddly enough,it's a spoken word that is my best souvenir. In another Berlin museum, I was reading the English version of a German wall text about a so-so Expressionist artist. He grew so depressed by conditions in Berlin under Hitler that he withdrew to a remote island. An older woman standing next to me, reading the German text, blurted out, "Dummkopf." What did she mean? Should he have stayed and fought Hitler? Should he, as a Jew, left the country entirely? Did she realize that "Dummkopf" is one of six GermantermsI actually know? Had she read my mind, since I too construed he had been a total idiot?

Did she really say "Dummkopf"? The ears can be as deceptive as the eyes or the camera.

But in the visual arts the eyes usually rule. When I was teaching at the School of Visual Arts, I developed a student exercise that is worth repeating: Ruin the Art. In your imagination, reinstall (relight, etc.) a gallery or museum room that displays acknowledged masterpieces, but make the art look really bad and uninteresting. I would liked to have done this with real art, but that was logistically prohibitive. The corollary assignment would be: Correct the Art. Make really, really bad art look good by placement and lighting.

My new assignment would be photograph the art to (a) make it look better than it actually is and then (b) worse.

Of course, some artworks simply do not photograph well no matter what you do. Could it be they are not really art? Most people know artworks from photographs. It would be as if we rejected certain plays simply because they could not be turned into decent movies.

Dale Chihuly, famous for his glass art, once scandalized a certain art school where he was teaching in the '60s by refusing to look at actual student work for an MFA critique. He would look only at slides of the work, on the grounds that this was how all art was usually judged and communicated. Some artists spend more money on photography than they do on art supplies, and I am sure it pays off.

Photographs of art can also cause disappointment. How many times have you been chagrined when a beloved painting, known to you only by postcard or slide projection, turns out to be grimy and forlorn? It takes a real connoisseur to understand that up close and real, Mondrians are not as neat as they look in reproductions. And that Blue Period Picasso you once adored (when you were 14) is actually kind of small and stupid-looking in real life.

Photography has influenced sculpture as much as it has painting, although it took sculpture longer to adjust to the camera. The pure, pure minimalist idea that you should be able to grasp the shape of a sculpture (or "specific object") from one point of view -- hence the justification for simple, familiar geometry -- is camera-induced as much as crypto-Platonic.

Photographs in art magazines are particularly influential.The so-called finish-fetish painting and sculpture that once characterized California art was generated by the clean-look of Hard Edge New York art as presented in the art magazines, rather than the friendlier surfaces one might know in real life.

And slide projections, like images on your computer,are so vivid and glowing that how can any art live up to them?

* * *

Exterior of Noguchi Museum, 2004. Photo: J. Perreault

All of the above came about because I was viewing my digital snaps on my computer, trying to figure out which one would make the best illustration for a short piece on the newly reopened Noguchi Museum.

Does the image above distort the Noguchi Museum? Make it look better or worse? Does it tell you anything about how I feel about the museum?

Next week: Is the Noguchi, near the East River in what some of us know as the working end of Queens, worth visiting? How did the $13 million renovation turn out? Is Noguchi a great sculptor?

AgainstPhotography

Dora Marr, Blind Beggar, 1934

Why have I written so little about photography? Possibly because, unlike in other areas, my taste is quite narrow. I obviously like Weegee; Diane Arbus is another star in my book; and John Coplans, if he really was a photographer. He certainly wasn't a photographer in the same sense that Weegee and Arbus were, but more in the category confirmed by Cindy Sherman's identity photography. I say "confirmed" because even Sherman has predecessors -- none, however, quite as dedicated to the fictionalization and, has been claimed, the demolition or decentering of self that is Sherman's m.o. (modus operandi).

I like Larry Clark's Tulsa photos, Nan Goldin's project and a few other photos here and there. I am interested in subjects. I am not entranced by consensus reality, which, since the invention of photography, is photo-reality. I am interested in realities that are not strictly visual. How something is seen is more important to me than how something looks.

For how something looks, you can't beat Vermeer. The details change, but the look stays the same. A silver bowl or a lock of hair in Vermeer and the chrome of an automobile or the teeth of a movie star all look the same to me. That Vermeer probably used a camera of sorts does not explain his hyperreality; it is instead the steadiness of his line, his colors, his hand and the icy way he treats space. Photography treats space like just another shape.

Early in the 20th century, after supposedly destroying realistic, representational painting, photography paradoxically struggled to escape frompainting. Yet, I firmly believe: worse than the photography that tries to be painting is most of the photography that tries to be smart. At least the former has a kind of absurd madness to it, albeit totally bourgeois.

There are, however, kinds of nonart photographs that I do like: snapshots (but only when they have been discarded, have writing on them and/or are within lovingly pasted but abandoned photo albums); real-photo postcards, and what I call Zen photography.

Snapshots are best when they have been discarded as not emotionally accurate enough (i.e., sentimental enough); when the focus or composition is not like all other snapshots (i.e., "reality"); the likeness does not correspond to what either the photographer or the subject expects to see (i.e., "truth").

Or have these images been discarded because the love involved in their taking has flown?

In this regard, willfully damaged photographs are the best. What has happened to all those images of brides (or grooms, I suppose) scissored out or merely ripped apart from their mates? What does it say about the mother who, when her daughter gets divorced, goes through all her photographs of the once-happy couple and destroys the offending male? Using an Exacto knife?

Photo albums also have their charms. I once found an intact album at a charity sale on Staten Island, put together by a member of a family once housed in a supervisor's cottages at what was then Sailors' Snug Harbor.

Snug Harbor, now a cultural center, was once (according to a stained glass window in the 1831 Main Hall) a "home for aged and decrepit sailors." It was founded much before Social Security and Medicare/Medicaid. The Supervisor (he was the chief chef) and his family, as evidenced by the 1920-39 photo album, often visited relatives in Asheville, North Carolina, another one of my favorite places. The son and daughter mature, almost page by page. There are motor-tours; there's larking. Group photos of the kitchen staff. And then it all stops. Ten black pages. Did Father loose his job? Wander off with the woman of pleasure from the nearby saloon on Richmond Terrace? Or did they all simply move to Asheville, where their relatives were, inexplicably leaving their album behind?

Abandoned photo albums are even sadder than snapshots thrown away. Whole lives (systems of illusion, in any case) have been cast into the dust-bin of history.

Real-photo postcards are perhaps easier to explain. There was a brief fad for black-and-white photo postcards, disasters like the great San Francisco earthquake or lesser catastrophes being the preferred subjects. Unlike the color postcards, often printed on "linen," there is no apparent alteration of the photo image. Most interesting are the local and personal real-photo cards. When you go to a postcard bourse and seek out real-photo cards, sometimes labeled as "Actual Photographs," you will find that they are arranged in categories. You will often be asked by helpful dealers anxious for sales what your category is. Would you believe, dead dogs in the road, Indianapolis, torture scenes, midget weddings, head-on collisions?

And then I like what I call Zen photography. Over the course of many predigital years I have taken hundreds, maybe thousands, of 35 mm slides, usually of outdoor sculpture or outsider yard art (on the theory they will always be useful for slide lectures). And then there are all those images of trips to Japan, Brazil, Iceland, or wherever. In filing them away -- not a task I looked forward to -- I kept a special little place at the end of the alphabet for end-of-the-roll accidents and other mistakes, more often than not abstract, some of them looking more beautiful than Color Field paintings. My finger on the shutter-button took the picture.

I have tried shooting at random without looking through the lens or shooting using some prearranged pattern, and nothing gets as good results as a real photo accident. This January, while photographing some industrial ruins in North Philadelphia I slipped, digital camera in hand, on some ice concealed by a layer of garbage. But lo and behold, my camera caught a blurred metal structure as I fell, and then a mysterious, brick-red monochrome. That's what I mean by Zen photography. Just as, in Zen archery, the arrow is supposed to shoot itself, in Zen photography the photo takes its own picture.

And then there is the whole category of surrealist photography, which leads us to the Dora Maar Problem.

* * *

The Dorsky Gallery (11-03 45th Ave., Long Island City; #7, Courthouse Square stop) is a beautifully appointed nonprofit art space that focuses on affording curatorial opportunities. There are always guest curators. My advice is that anytime you are visiting P.S.1, you should walk a few blocks over to the Dorsky. Curators need to be encouraged too.

In this case, "Dora Maar: Photographer" (through June 28, Thu.- Sun., 11-6 p.m.) is as much for Picasso addicts as well as for photo fans. Maar's relationship with Picasso is well-documented -- not here, but in the master's oeuvre. For a time she was his favorite model as well as his amour. According to the essay by guest curator Victoria Combalia (in Dorsky's typically classy, trifold pamphlet), Maar and Picasso met, as they say in the movies, "cute," but cute by surrealist standards. The poet Paul Eluard...

...introduced them at the press conference of the Jean Renoir film Le crime de Monsieur Lange, for which Maar was a photographer. This meeting took place before the famous episode at the Parisian café Les Deux Magots in which Maar supposedly seduced Picasso by playing a knife game that caused her fingers to bleed.

Previous lovers had been, yes, Eluard and then Georges Bataille, which might have been enough. But Picasso opened the doors of posterity. What at first might seem a blessing turned out to be a curse. Those lovely, blood-stained fingers are on every print -- pre-Picasso, Picasso period, and post-Picasso. If you Image-Google Maar, you will see endless Picasso "portraits" of her, a few homage-to-Maar lamps by ceramist Jonathan Adler, and perhaps four photographs of her own, over the course of 12 Image-Google pages!

By the Google standard, she was a failed photographer. But a successful artist model and muse.

How do we judge her photographs, now that we care very little about her relationship to Picasso? We judge them like any other art. If the Dorsky Gallery exhibition is a fair sampling, the work, alas, is not all that consistent. Compared to Lee Miller (1907-77), Maar never developed a strong personal vision. For Miller -- a great beauty herself and not unconnected to the Parisian art world -- it was her war photography that finally freed her from the aura of her liaison with Man Ray. She gained fame from her photographs of the London blitz and of the battlefront. Her famous photograph of a dead German soldier is too gruesome to grace this screen, although I suppose one could argue that it tells you what war is really about.

Then too I have direct evidence about how willful Miller was. As commissioners of the first (and I think last) Tokyo Biennial of Figurative Art, we men were celebrating the completion of the jurying process in a former 19th century palace with a view of Mt. Fuji. It was now a geisha house of high repute. Miller insisted that she accompany her husband, Sir Roland Penrose. This was unheard of, but she persisted. And the Japanese solution was that all the wives of the Japanese commissioners were asked to attend the dinner party also, much to the amusement and slight confusion of the geishas. Each wife was assigned a geisha, just like the men.

To be fair, Maar did now and then have to make her living doing fashion photography. Did she compensate by photographing beggars, blind men, and urchins in the Parisian streets? I find most of these photos too sentimental. We know she was a pal of the Surrealists, but her efforts at photo-collage, aside from Femme tenant a la main l'image de son proper visage, 1931-37, with white paint, do not convince. She also ended up in a mental institution for a while, until released by Eluard, with the aid of Jacques Lacan. We want to see those post-1945 introspective and mystical paintings mentioned in Combalia's essay. And yet...

She created at least three "masterpieces."

1. Blind Beggar, 1934, is of a seated man holding a peculiar package as if it is the infant Jesus, either still-born or a victim of crib death. The expression on his face, as with tilted head he appears to look off to his right, is one of the great face-pulls in art. Leaving aside the ethics of photographing a blind beggar (or my using of the image above), it can be described only as an inadvertently beatific, what-am-I-doing-here look.

2. Man Looking Inside a Sidewalk Inspection Door, c. 1935, with no face visible, shows curiosity with the body alone. It could also be called Ostrich. Or The Art Critic. Here too, the accidental looks meaningful: the trap-door key to the inspector's right on the pavement; his left hand flat on the ground, elbow straight up; the lift of the left toe of the approaching pedestrian, who is also headless but because of the photo rectangle.

3. Portrait d'Ubu, 1936, is the most marvelous Maar. As someone who -- strangely enough -- has as an artist been compared to Alfred Jarry, how cannot I but love this homage to his proto-Dada stage monster of all time? Does it really depict "the fetus of an armadillo" or is it something worse? Unfortunately, it is not in the Dorsky exhibit, but you can see it by clicking here.

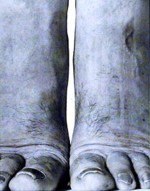

John Coplans: Self-Portrait (Feet, Frontal), 1984

The Body Politic

Oddly enough, one of the best essays written about Weegee, last week's subject, is by John Coplans (1920 - 2003), this week's subject. His essay, titled "Weegee the Famous," is in Weegee's New York (Schirmer/Mosel, 1982). He erred, I feel, on the side of attributing too much naiveté to that artist's brutal vision. But this is how cults are born:

No other art form rivals photography's capacity to be meaningless, to topple into a void. As a hedge against vacuity, ambitious photographers cloak themselves in a knowledge of art. But Weegee was an innocent, a primitive who described strong emotions and guilelessly jabbed at ours.

About as innocent as a second-story man caught on a fire-escape with the goods. About as primitive as Goya. About as guileless as Gypsy Rose Lee. About as innocent, primitive and guileless as Coplans himself.

Writer, curator, editor, artist -- Coplans is my kind of guy. (I am a writer, curator, editor, artist myself. And poet. And sometimes actor: I played Vincent van Gogh on Dutch National Television. And artist's model: Philip Pearlstein, Alice Neel, Sylvia Sleigh, Eleanor Anton, etc. The future belongs to the polymaths, but we never know how it will all shake down.)

Until the '80s, Coplans whom most knew only as an editor, was also a curator and writer, but he had begun as an abstract painter. Now, after his death, I am sure he will be best remembered for his photography, and certainly not just as a founder of Artforum or one of its most daring editors (1971-74); nor because, when he was senior curator at the Pasadena Museum of Art, he gave Ellsworth Kelly, Robert Irwin, Roy Lichtenstein, Richard Serra, James Turrell and Andy Warhol their first museum exhibitions; nor for his Abrams tome on Ellsworth Kelly.

In Challenging Art: Artforum 1962-1974 (see my March 7 essay in the ARTOPIA Archive to your upper right), James Monte says that at the time of the founding of Artforum in San Francisco, Coplans was "a very good painter, hard-edge painter, much like Ellsworth Kelly with very simple shapes."

Are those hard-edged, simple shapes echoed in his photographs? I haven't seen the paintings, so I don't know. I suspect there is a formal resemblance. Nevertheless, the subject matter, as in Mapplethorpe's most notorious works, will all but erase the geometry, the studied push-and-pull, the classical design. Just as well; we have already seen enough of that.

But do we really want to see close-ups of an old man's flabby, mole-flecked, wrinkled body, sometimes even with the penis and the testicles exposed or, as in a famous, earlier Vito Acconci Body Art piece, pressed and hidden between the thighs, making the old man that some of us shall become also an old woman?

I knew John Coplans hardly at all. I did not once write for Artforum when he was editor. But judging what I wrote in the Soho News, I was upset when he got fired.

My most vivid memory of Coplans, however, was well into his photography career. A filmmaker wanted a place to interview various people about the West Coast ceramics luminary Peter Voulkos, and Coplans generously donated his small loft in Soho. This was fine, but Coplans was there during the interviews, including mine, with more than enough booze in him to inspire his constant interference with the shoot. The old goat.

But his photographs! They make up for all his faults.

You can see the vertical triptychs that compose Serial Figures of 2002 at Andrea Rosen (525 W. 24th St., through June 26) and, if you can stand Madison Avenue and being jammed into those tiny elevators, earlier work going back to 1982 is at Per Skarstedt Fine Art (1018 Madison Ave., through June 26). The Skarstedt show is an essential catch-up.

If for some reason you wish to know more about Coplans' life than Challenging Art provides, check out at the Smithsonian's American Art Archives, where an interview by Paul Cummings takes us up to 1975. And although surprisingly uncorrected (names!), it gives a flavor of Coplans' anti-Brit South African voice. I was particularly impressed that at the age of 40, he left swinging London and headed to America, without a job and hardly any money.

But to pick up where the American Art Archives lets off: after being fired from Artforum (read near the end of the AAA interview his theory or theories why), he moved on and founded Dialogue, the Midwestern art tabloid. Then in 1980, as a wall text at Andrea Rosen states, he gave himself what he called a "Watkins Scholarship." He sold his collection of Carleton Watkins photographs, which enabled him to produce his own body of artwork. (He also collected the great potter George Ohr; examples are on display in the room that summarizes Coplans' achievements.)

Totally plugged into the art world, surely Coplans knew the Body Art of Acconci, Robert Morris' leatherman self-portrait, Mapplethorpe's exhibitionist scandals, and Lynda Benglis' famous dildo ad in Artforum. But more relevant to his work would be Hannah Wilke's documentation of her mother's wasting away in illness, and above all Alice Neel's great nude self-portrait at the age of 80.

In a world of buff "beauty," age and aging are taboo. No one likes to be reminded of mortality. Of course, Coplans turned his own old man's body into landscape, and he himself, as is the case with much self-portraiture, hides behind his honesty. Starting at the Skardsted minisurvey -- hands, feet, torso, etc. -- and in the larger, six-foot-high late self-portraits at Andrea Rosen, there's no doubt that Coplans framed and edited the image of his own body into dynamic fragments. The full body is never seen, although the late works come close.

Did Coplans produce photographs that relate to Body Art? Coplans' relationship to Body Art is complex. In my view, Body Art was a kind of sculpture performance. Living sculpture would be the closest game. The body of the artist became the sculpture. It is a commonplace that all sculpture is a stand-in for the body (i.e., all sculptures are statues). This is reversed in Body Art: the artist's body is the stand-in.

Some academics show their ignorance when they claim that Yves Klein's use of live models to make paintings is a Body Art prototype. But seeing Duchamp's cross-dressing RroseSelavy is perfectly justified in this regard. Rrose is Marcel. More contemporary examples would be Robert Rauschenberg (as a dancer), Carolee Schneemann (in almost everything), and Ana Mendieta when she used herself as a kind of temporary earthwork in the landscape.

Coplans, since he chose photography, produced Body Art only in the same sense that Cindy Sherman has in her self-portraits. Body Art and set-up photography merge. Photography was the way to communicate Body Art. Photography became the way to sell both identity and the body.

* * *

But I would also like to claim that the biggest influence on Coplans was not any of the artists I've mentioned, but Weegee. I will pull some sentences from his text on Weegee and you'll see that the same words can apply to his own photographs.

Coplans, like Weegee,

belongs to a very American photographic vein, to tell it like it is. But the extremes to which he was willing to take this rhetoric make the viewer's complicity in it apparent.

He, too, could be transformed into a fit subject for the kind of brazen exposure he visited on others.

In one sense his images were no less or more than ghoulish still-life to him.

His own tawdriness led him to where few other photographers were willing to go, and gives a terrible edge of remorseless tension to some of his images.

Finally, our awareness of Coplans' excitement promotes these images of ostensibly banal horror to a level of artistic horror which is capable of moving us.

AJ Ads

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Exploring Orchestras w/ Henry Fogel

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary

Tyler Green's modern & contemporary art blog