main: March 2004 Archives

AAA Corp, TransmissionTour, The Wages of Fear #01

The Use-Value of Art

There must be something to Jung's idea of synchronicity. Or did my brain store away some dim memory of a press release? In any case, after last week's exposition of my categorical risk concept --inspired by the Lee Lozano exhibition at P.S.1 -- here is an exhibition on related matters, "The Future of the Reciprocal Readymade," curated by Stephen Wright for apexart (291 Church St., south of Walker, to April 17.) Yes, there is art outside of Chelsea. This nonprofit in Tribeca specializes in guest curators who produce thematic shows, often of dubious thematics but sometimes very interesting indeed. The current show is exceptionally adventurous. You should also know that the subtitle, "The Use-Value of Art," refers mostly to Duchamp, not Marx or Hegel: specifically the great Dadaist's 1916 note to himself to "use a Rembrandt as an ironing board."

"Reciprocal Readymade" consists of works by eight, relatively anonymous art collectives. The curator claims they produce works that, though informed by art competency, are usually not perceived as art. I say "relatively anonymous" because in two cases you can go online and find some names.

How does the curator gets around the paradox that he is showing works of art that are not meant to look like art, in an art gallery where they are, of course, perceived as art, or at the very least as art proposals? Critical Art Ensemble's Contestational Biology Project has already been on view at the Corcoran in D.C. in 2003. Although it is not clear if the piece was actual discarded gasoline containers and/or photographs of them, xurban's The Container Uncontained was included in the 2003 Istanbul Biennial.

Here's the solution: Wright cleverly writes in the glossy apexart four-fold that the exhibition is intended as a resource: "...What should a project that sees art as a latent activity, rather than as an object or a process, physically look like? More like a walk-in toolbox than an exhibition; like an open toolbox, full of the ways and means of world-making."

Taking a cue from the Rembrandt ironing board idea, which suggests that art can be made to have uses other than the standard ones, I'd say that we have already been here before -- for example, with Hans Haacke's real estate analysis and art-system documentation pieces, not that these ideas cannot be further explored. More problematic and more inspiring is the apexart essay subtitle "Art Without Artists, Without Artworks, and Without an Artworld."

In some cases, we have art that is so much like political protest that it partakes of categorical risk. It becomes art by calling into question whether it fits into the art category. I am thinking in particular of Critical Art Ensemble's attempt to reverse-engineer genetically modified canola, corn and soy plants. Critical Art Ensemble also publishes somewhat opaque books of the philosophically anarchist sort, but maintains a nonsaboteur, non-eco-terrorist stance they prefer to call Fuzzy Biology Sabotage. The Flesh Machine, available free on their website under Book Projects, is here the most relevant.

A second example of categorical risk would be the giant poster handout produced by Bureau d'etudes (Paris). It maps all kinds of international "world government" connections. World government means "an intellectual complex, which is able to coordinate, accumulate and concentrate the means for defining the norms and determining the development of capitalism." It's a huge and detailed flow-chart that links governments, corporations, families, think tanks, etc. It's free; the shock here, I imagine, would be receiving it free on some street corner. You certainly couldn't take it all in, but it would have a certain weight.

Third, I would select Grupo de Arte Callejero (Buenos Aires) for their genocide project maps, and stickers pointing out the homes of the still surviving and, one assumes unpunished, government participants in the disappearances that took place during the late dictatorship.

I have already mentioned above the problematic nature of the work(s) of xurbn.net (Turkey). Their website, proclaiming that it is an Istanbul/New York portal, documents the trail of illegal petroleum containers. The giveaway is the reference to Foucault, which means the site is too fashionable to be art that tackles categorical risk. Communication does not equal art.

AAA corp. (Saint Etienne, outside Paris) makes patched-together mobile radio studios and silk-screens to advertise the station and the programs, reminding one of hippie or guerrilla theater. Therefore, whatever they are doing can't really be art, can it?

The Yes Men(Paris) are represented by a dumb deck of cards: George Bush Sr., Rupert Murdoch, Saddam Hussein, Michael Powell (head of FCC), Thomas Hicks (vice chairman of Clear Channel), and others. The Yes Men website is even more fun if you want the call-for-proposals for new coin designs issued by the U.S. Treasury Department or need to know exactly what to do on international Phone in Sick Day. Anticorporate pranks? Can't be art!

Most moving, however -- yes, even reciprocal readymade art can be emotional -- is a video piece by The Atlas Group (Beirut). Their website proclaims the group was founded to document the contemporary history of Lebanon. Hostage: The Bachar Tapes is admittedly a fictional recreation of an interview with an Arab hostage. But I Only Wish I Could Weep by Operator #17 is sheer poetry, whether fictional or not. The tape was supposedly sent to The Atlas Group by Operator #17, who was employed in 1992 as one of the camera operators secretly filming people walking along the Comiche, Beirut's seaside walkway: "the favorite meeting place of political pundits, spies, double agents, fortune tellers and phrenologues."

Operator #17 was caught panning to sunsets instead of staying focused on the people, seen here mostly as silhouettes against the sea and sky. He was fired, but allowed to keep his sunset footage, which is what we are shown.

* * *

Art without artists is Outsider Art, Group Art or Collective Art

Art without artworks is leaflets that are all given away; ephemeral art; performances and Streetworks, but only if undocumented.

Art without the art world is unassimilated, non-European art and anonymous folk art, liturgical or meditational art; personal art and amateur art.

* * *

Is what we see at apexart art disguised as a radio station, a contemporary history archive, a flow-chart, an oil container, sprouting seeds, political slogans, a deck of cards? Or are we really looking at a radio station, a contemporary history archive, a flow-chart, an oil container, sprouting seeds, political slogans, a deck of cards pretending to be art?

In other words, are the works political agitation disguised as art or art disguised as political agitation? Which work belongs to which category?

Finally, one might wonder if it is really necessary to view this exhibition. You need to see Ensemble's pots of dirt, see the Bureau de'etudes handout on the wall -- and take one from the giveaway wall-sleeve. Although the exhibition format provides a context of thought that the internet would not, most of these works could probably do just as well on the net. I don't think its any less boring to read something on a wall label than on a computer screen. We know a photograph in a magazine or a book is different from one on a wall, but an image on a computer screen is different from both. Think about it. A computer screen is more like a lightbox than either a page or a picture on a wall.

If it weren't for the fact that the San Francisco Museum of Art, the Dia Foundation, the Walker Art Center, the Whitney Museum of Art and other stately venues already offer art made specifically for the internet, one could say that internet art approaches categorical risk. It only does so when it doesn't immediately look like art.

Lee Lozano, Untitled Drawing, n.d.

A Method in Her Madness

What is one to do with Lee Lozano (1930-1999)? A free-ranging survey of her art at P.S.1 in Queens (through April) prompts some thoughts. First of all, we get to see several bodies of work: large paintings and drawings of tools; drawings about sex, sometimes with tools as sex instruments; abstract paintings (but not her justifiably well-remembered Wave Series); and conceptual/performance pieces as spelled out in her notebooks.

The tool paintings recall the German painter Konrad Klapheck, but at their best are bigger, more expressionist and more menacing. The sex drawings point to Philip Guston or R. Crumb, but have a turbulent edge; the abstract paintings are both minimal and sublime; the conceptual works are dangerous. We get four careers, four styles, four takes on art for the price of one. Is this good or bad?

I particularly liked North South East West, last shown at the Corcoran in D.C. in 1969 but now reconstructed in P.S.1's two-story Duplex space. It is an exceptional work: four widely separated canvases with arcs on each that if extended would describe a very large circle. It is certainly as good as the 11 paintings in the Wave Series.

Here I have the advantage because I saw and still remember the Wave Series (1967-1970) when it was shown at the Whitney in 1970. (For various reasons it could not be included in the current exhibition.) All 11 are owned by the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford. Lozano wanted the paintings in the series to remain together as a single piece, and so they have.

Using the vast resources of my personal library I actually found the pamphlet produced by the Wadsworth Atheneum when the Wave Series and some of Lozano's notebook pages were shown in 1998 in MATRIX 135. (MATRIX is the Atheneum's ongoing series of intensive investigations of new art. MATRIX 152 is now offering "gangsta geisha" works by Iona Rozeal Brown, who is apparently fascinated by Japanese youth obsessed with hip-hop culture. Classic geishas are shown in blackface.)

From James Rondeau's essay I learned Lozano wanted the paintings exhibited leaning on black walls to better show off the textures and sheen. I also learned (or perhaps re-learned) that the "waves" in each paintings were made in one continuous working session according to a preordained arithmetic. I remember them looking as if the paint had been raked by special combs, but now I know they were actually laboriously and meticulously applied by brush.

At P.S.1 it is relatively easy to sail through the big tool paintings, the sex drawings and the few minimalist paintings, but the last room is the problem room, displaying the notebook pages she considered drawings. Some of these pages are as raunchy as the sex drawings, yet here and there are sentences of strange illumination.

In regard to the cool North South East West, Lozano quotes Buckminster Fuller, inventor of the geodesic dome and a '60s guru sacrificed to the ravages of cynicism and anti-utopianism: "As soon as I complete the drawing of a circle, I wish to be outside of it." Or her own thought: "At the center of circle is Beelzebub's bung-hole." But this is balanced elsewhere by "I WILL MAKE MYSELF EMPTY TO RECEIVE COSMIC INFO."

This is the same year (1969) she painted North South East West and was still working on her Wave Series. In 1969, everything was going on at once. To some, the sex drawings and the notebooks will look a bit mad. The emotions are so raw and angry.How then can we account for the minimalist paintings? Are they merely a lucky break, or are they also "mad" -- but with the madness of repression?

The wave paintings are a strange caesura. Did she here wake up or here fall asleep? Since Lozano, like all of us, was probably composed of several minds, did one such center suddenly gain or lose control? Or -- and here reason must play a role -- is it merely that we foolishly require continuities and are confused when such rules are broken? Perhaps she herself could not handle these discrepancies.

Lozano is an artist who cannot be packaged. After her Art Strike piece, in which she instructs herself to withdraw from the art world, she decided to boycott all women, which seems to mean not speaking to or having any dealings with anyone of her own sex. We are not privy to what led to that extreme stance, but I cannot believe this pleased some of her biggest supporters -- for instance, feminist critic Lucy Lippard. To make matters worse, Lozano moved to Dallas, Texas.

But perhaps her biggest sin is that she was furious at the art world, not just at the usual suspects but at her fellow artists, too. Here are two 1969 pieces reproduced in the MATRIX pamphlet:

Art Piece (or Paranoia Piece):

Describe your current work to a famous but failing artist from the early 60s. Wait to see if he boosts* (*hoist, cop, steal) any of your ideas.

Real Money Piece:

Offer to guests coffee, Diet Pepsi, bourbon, glass of half and half, ice water, grass and money. Open jar of real money and offer to guests like candy. [The "guests" were all artists: Hannah Weiner, Steven Kaltenbach, Keith Sonnier, Dan Graham, etc.Some took money, some borrowed money, some did nothing.]

The questions raised by these and other "pieces" in her notebooks -- most self-assignments, some dealing with drugs, some with masturbation -- are worth thinking about. Can you make art only for yourself, or is art necessarily social? Can something be art even if it is not recognized as art? Can you make art outside the art system? And if so, to what end?

Did Lozano intend the scrawlings in her notebooks as art? I'd say yes. Some of them were exhibited in the Dwan Gallery. She was, as it were, on the scene. The participants referred to in her Real Money Piece prove this. She knew activist critic Lippard and Sol LeWitt and was friendly with many others in the art world.

And she most likely knew the work of Vito Acconci (who at this point did an artwork that consisted of walking around St. Patrick's Cathedral over and over again) and of Adrian Piper (who, intentionally reeking of garlic and other so-called bad odors, stood in movie lines as an artwork). Or of Scott Burton, who walked on Manhattan's 14th Street in full drag, totally undetected by friends and other artists. Hannah Weiner, whom we know Lozano knew, contacted and met with another Hannah Weiner listed in the phone book; she hired a hot-dog cart and renamed it Weiner's Weiners. And she leaned against a doorway on the Bowery pretending to be hooker during one of the time- and location-bound mass Streetworks yours truly helped to organize in -- you guessed it -- 1969. Lozano may have even known of my own ongoing Streetwork: Any time I am recognized in the street by someone I do not know is a Streetwork.

Many of the Street Workers and guerrilla performance artists and poets either documented their works themselves (some documents were, alas, destined for galleries) or participated in mass situations that made documentation likely, even if only in the pages of the Village Voice, the East Village Other or Vogue.

Lozano herself seems not to have had any consistent goal. This is why many of her performances, which were either private "dialogues" or, more important, instructions to herself alone (unlike Yoko Ono's earlier command pieces that can be performed by others), partake of what I have now come to call categorical risk.

* * *

The important thing about Lozano is not that she embraced wild erotic art, cool minimalism, and private performance art, but that in so doing she engaged in categorical risk. Serious art, because it must make the viewer -- and perhaps even the artist herself -- ask if what they are looking at is art at all, is art that engages in categorical risk. The same can be said for an unusual art career or an atypical, perhaps inconsistent, oeuvre. As Lozano wrote: "Seek the extremes, that's where all the action is."

Those involved in Streetworks were testing audience boundaries. An action or an object could be art even if the audience -- often accidental and uninformed -- does not know the action or object was intended as art. This "audience" might not even have art as a category of reference, never mind knowledge of arcane works by Kurt Schwitters or Marcel Duchamp. Lozano took an additional categorical risk: There did not have to be an audience or viewer other than herself.

Can we deal with that? Given the premise, one might never know if the person sitting across from you on the subway is or is not an artist. His little snooze may be his performance piece, or whatever he is or is not thinking about might be his conceptual art.

We already know from Outsider Art that a maker can create art without intending to and, in fact, may not even grasp the art category, but instead be proselytizing for some vision, praying or performing odd and grand magical techniques.

But artists embracing categorical risk are doing so consciously. Categorical risk is the key characteristic of important modern and postmodern art. Unlike normal art, which looks like and even smells like art, the art of categorical risk induces doubt (at least at first) that it even belongs in the art category.

The philosophically inclined should know that by "categorical" I do not mean absolute, as in Kant's categorical imperative, which is usually defined as a moral obligation that is unconditionally and universally binding. Although I do like to think of categorical risk as being the absolute and binding art definition of our time, I think we need a little leeway, since categorical risks are now often immediately absorbed. Some risks are riskier than others. And then again, just because something doesn't look like art or act like art doesn't automatically make it art.

Some historical examples of categorical risk will serve to clarify my term: the first cubist, futurist, constructivist paintings; Duchamp's signed urinal or his bicycle wheel; Pollock's drip paintings; Yves Klein's jump, but also Allan Kaprow's Happenings and Joseph Beuys' lectures. More recent examples might include Mike Bidlo's Picassos, Pollocks, and Warhols; Damien Hirst's preserved shark, Jeff Koons' glass porn.

The best art work in the P.S.1 show is Lozano's 1969 General Strike Piece:

GENERALLY BUT DETERMINEDLY AVOID BEING PRESENT AT OFFICIAL OR "UPTOWN" FUNCTIONS OR GATHERINGS RELATED TO THE "ART WORLD" IN ORDER TO PURSUE INVESTIGATIONS OF TOTAL PERSONAL AND PUBLIC REVOLUTION.

Lee Lozano was stepping off into the void (in a bigger way than Klein's faked dive). She left the art world!

Yayoi Kusama, Fireflies on the Water

Part One: The Serious and Ambitious Catalogue

Yayoi Kusama, Fireflies on the Water

Part One: The Serious and Ambitious Catalogue

Twelve Years That Shook the Art World

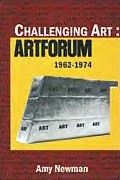

They were so young, so committed, and so smart -- according to themselves. But shouldn't we add self-deluded, pompous, and ruthless? The evidence is all there in the self-serving statements, contempt for others and general viciousness of the editors and writers of Artforumas recorded in Amy Newman's breathtaking Challenging Art: Artforum 1962-1974. It's now in paperback and a good beach-read even when it's too cold for the beach. I cannot count how many times the word hate is used. The vendettas are hilarious and sad.

Here are some sample quotes:

Philip Leider, editor of Artforum from 1962 to 1971, on art critic and film historian Annette Michelson: "She lived in Paris for a really long time. And when nobody knew what in the world structuralism was, except Annette, she gave a talk on the subject at the Guggenheim. You either followed her or you didn't. And she never lowered her standards to even my level. I never understood what she wrote."

"Why did the writing become impossible to understand?" asks art critic Barbara Rose, whocalls Earth Artist Robert Smithson's writings for Artforum "campy." "Annette, after all, lived in France for so long her syntax is French. Max [contributing editor and critic Max Kozloff] was never a clear writer. Opacity was maybe unintentionally part of his style. Later it had nothing to do with a reserve about communication, it made it all look very deep and profound and it confused people and it was a way to keep people out, which was not the intention to begin with at all."

"I remember having this big argument -- it was when I realized how deeply I hated Lawrence Alloway -- about whether or not there was such a thing as an aesthetic experience," says critic Rosalind Krauss. (Alloway was the British-born critic and curatorwho coined the term Pop Art.)

Michael Fried (art critic) on a lecture by everyone's hero Clement Greenberg: "I don't remember much about the lectures. But they were Clem at his most apodictic. Naturally he didn't show slides, he didn't believe in them, and besides he despised art history lectures and the apparatus that went with them. So you had Clem talking, making absolute pronouncements, and of course we were very pro-Clem."

Oh, Rosalind, Barbara, Michael, and Annette et alia, how foolish and arrogant you all were. Some of us knew it then, but now it is confirmed in your own words. The second batch of Artforum writers, when the late John Coplans was at the helm, was equally contentious butless tyrannical, perhaps because Greenberg was no longer a model or father figure. Kozloff, no stranger to the art wars, acquits himself well. Alloway had already passed on when these interviews took place, so we miss his wit.

To construct this art world bodice-ripper, Amy Newman interviewed all the editors and contributing editors -- and many of the writers -- in and out of the mix. The subjects were allowed to read and alter the transcripts, which is not good journalistic practice but one that art historians allow: it's for the record, and we want to get it right. Ifthe "speakers" look foolish, they have only themselves to blame.

Chunks of the interviews were woven together chronologically and then thematically: 1962-1967, 1967-71, and 1971-74 are each divided into "Isms" and "Schisms" sections. These are further separated into subtopics. For instance, the 1971-74 section mines topics ranging from "Rocky transition / The new regime / Cabals of hatred" through "Culture wars II: Modernist imperialism" to "Less like 'Artforum.' "

The result is like a marathon, no-holds-barred panel discussion that might have taken a week or so, but would have had graduate students hanging from the rafters and everyone else convulsed with laughter or in a stupor of boredom. Of course, after a certain point most of the "participants" could not stand to be in the same room, never mind on the same dais. "Over my dead body" would likely be the operative phrase.

What blood was spilt! What spleen was spewn! (Or whatever you do with spleen.) And it continues. But who now cares? It just makes a good, mean story. Some may wax nostalgic for a time when a handful of people called the art-world shots, but I don't. Did we really want Fried and Krauss deciding what great art was? Someone had to be the opposition, so Earth Art could emerge. As we see, it certainly did emerge in the person of Robert Smithson. Smithson, as several report, somehow managed to rescue Leider from the clutches of Clem.

Unlike any magazine now, Artforum was the art-world Bible, but the art world changed and it all fell apart. The gatekeepers couldn't handle the gate. Under Leider, Artforum was a powerful force, mostly for Greenbergian formalism. Read this poignant summary, by the talented Maurice Berger, once a student of Krauss:

A few years ago, I received a dissertation proposal on the so-called Minimalist movement from a doctoral student. Two of the four artists she was working on -- Bob Morris and Eva Hesse -- I wrote extensively on. My work, of course, is revisionist. I read this young woman's proposal and it's 'Michael Fried this and Rosalind Krauss and Annette Michelson that.' She is writing in 1994 about Minimalism and she doesn't mention any of the revisionist texts on Minimalism written over the past fifteen years. This is my student and she doesn't even cite my own work on Minimalism, including my first book -- and the only monograph -- on Robert Morris. She's still so obsessed with the Artforum moment that she doesn't even mention the writing that has superseded it. I insisted that she a least acknowledge this other generation of writers.

There are a number of things to learn from the "Artforum moment." To have power, an art magazine must appear to have a position. It must have writers who, even if they cannot write, are passionate. An art magazine cannot be fair; nor can everyone be allowed to play. An art magazine needs the present-day equivalent of the $60,000 a year that Artforum got from publisher Charles Cowles' family to give him something to do. An art magazine has to be able to build up a huge debt and yet be able to refuse ads that do not meet its artistic standards.

It's all there. Did Leo Castelli pull those ads? Why did Greenberg threaten to sue? Did all the art magazines agree on an antiwar cover? Why were certain galleries always on the inside covers? What art magazine was notorious for selling its front covers? Why did an ad by artist Lynda Benglis, wearing a dildo, cause both Krauss and Michelson to resign?

And when the party is over and everyone has married well, founded another art magazine, gotten tenure, or merely been turned out into the storm, all the writers and editors should be required to give nasty, self-incriminating interviews.

* * *

On a more serious note:

What is my ideal art magazine? Let's put aside for the moment that it should always publish whatever I want to write, with only line edits and no content or style edits, illustrated with the images I choose, and with my headlines, for the minimum grand fee of$5 a word. This is what an ideal art magazine needs:

1. Twelve smart writers who can write what they want every two months.

2. Beautiful color illustrations.

3. To keep collusion under control, no advertisements for galleries, art spaces, artists, museums, or art books. Only national ads: cars, booze, furs (no, we had better not have furs), fashion, luggage, what have you. Then there's restaurants, framing shops, real estate ... travel agencies, escort services, law firms, insurance companies.

4. Why not publish the Ideal Art Magazine for free on the web? No, that won't work. The pictures will not be big enough and, according to Rockefeller's rule, if it doesn't cost anything, no one will take it seriously. The old man actually said that when asked if admission should be charged at the then-new Museum of Modern Art. So let's have an art magazine that takes no ads at all with a cover price that covers what it costs to produce, divided by the number of copies printed. If it costs $500,000 to put out each number, sent to a modest 5,000 subscribers, then each issue should be sold for $100. Any takers?

Still from Morrison: Decasia

Film As Art

Bill Morrison's film Decasia: The State of Decay is art. I don't mean to say that Hitchcock's Vertigo or any number of Dogma films are any less art. But Decasia is art the way Blood of a Poet is or Stan Brakhage's Mothlight or Bruce Conner's Movie or Andy Warhol's Empire are.

Decasia was originally created for a multimedia event, featuring the music of Bang-on-a-Can founder Michael Gordon at the Bridge Theater, then performed as a music-with-film piece for the Basel Sinfonietta.Although Gordon's music is fine by itself (and is also about decay), the original cart is leading the horse, for the film has a life of its own outsideits multimedia roots.

The sequences seem to be cut to the music, which now forms the soundtrack. But there was probably a good deal of back-and-forth between the filmmaker and composer.The music might be able to stand on its own, but I tried watching the DVD without the soundtrack. It's not quite the same, so I suspect that sound and image are integral.

Briefly, the viewer is led from a whirling dervish through various sequences of beauteous decay: nuns and children in cloisters, rescues, parts of a 1912 Pearl White film, an invasion. Then an hour or so later we are back to the dervish. In the interim there are gorgeous blooms, blobs, and even black-and-white inversions looking strangely like solarization. A boxer battles a "living" punching bag, ghosts dance, and ectoplasm seems to invade a heated drawing-room scene.

But the moving, amoebic, moldy blobs and blisters are the best. It is as if the flesh of vision is being devoured, all to the music of brake drums and eerie, out-of-tune pianos. And as a friend of mine volunteered, Decasia is a kind of time machine. Developing this idea, it is not so much that nitrate film stock is unstable, but that memory is.

Decasia fits into the category of a now largely ignored tradition: that of films meant to hold their own with painting and sculpture. Not, of course, as paintings and sculptures per se, but as films made outside the mass-media market and usually outside the narrative tradition, and within the modernist and postmodernist visual-art playing field.

Often, as modernists would have it, these so-called experimental movies are films-about-film -- as, in part, Decasia is. But that is only half the story. The other half is that they evince personal expression of a kind that Hollywood (or Bollywood, for that matter) can rarely afford, because of the group structure of the enterprise and the audience target. The New American Independent Cinema (too much of a mouthful to function as an effective tag, if you ask me), sometimes called Underground Cinema (better, but sounds more subversive than warranted), in full flame from the '40s through the '60s, was probably one of those glory moments that cannot be duplicated.

This is not to say that "underground films" (more likely these days to be digital-format video) are no longer made. As long as verbal language exists, somewhere a poet will be making a poem. So too, as long as there's an affordable way to capture and string together moving images, there will be an artist-filmmaker, videoist, or digitalist playing with, or even against, images in time. It's just that the discussion about avant-garde film like all discourse, had a half-life and has itself decayed.

The repressed topic, the subject that should be addressed, is this loss. Decasia is so good a film it should renew that discourse. This is the real importance of Decasia and not the journalistic emphasis on, say, the tragedy of disintegrating nitrate and the need to save so many films in so little time.

Painters and sculptors and even art critics used to attend screenings of new avant-garde, experimental films and argue about them. Independent art films were part of the art culture, as was music (John Cage speaking at The Club,John Coltrane playing at the Five Spot and the Cedar Bar) as was dance (Merce Cunningham). Many artists, I would guess, fantasized about making films. Some, like Red Grooms, made amusing films and some, like Alfred Leslie, made important ones (Pull My Daisy) that encapsulate the feel of an artistic milieu.

Now, when painters want to make movies, they want to make Hollywood films. This is okay if you are Julian Schnabel and actually have some mass-media talent, but otherwise, leaving aside the beautiful and moving wall projections of Shirin Neshat and the iffy epics of Matthew Barney, we can only mourn that film as art has been subsumed by film as entertainment .

Decasia, coming through the front door, as it were, of the popular press, may be the sign of change. A laudatory article by Lawrence Weschler (author of books on artist Robert Irwin and the playful Museum of Jurassic Technology in L.A.) in the New York Times Sunday Magazine in December 2002 was not really the kiss of death it could have been. Remember that Jackson Pollock's first big splash was in Vogue.

Decasia is imbedded in the film-as-art tradition; if you are conversant with that world you cannot look at it without thinking of Stan Brakhage's various scratched and painted films and, for the use of found footage, Joseph Cornell's sublime Rose Hobart. Yet,as it should be, Morrison's masterpiece is curiously new. It has been shown at various film venues all over the world, on the Sundance cable channel, at MoMA, recently projected on the wall of the Maya Stendhal Gallery in Chelsea (along with some new, but shorter, works), and is now available for purchase or rental in aDVDformat.

* * *

Also available on DVD, as of late last year, is By Brakhage, An Anthology, a two-disk set (the Criterion Collection) that includes 25 of that seminal filmmaker's efforts. Stan Brakhage (1933-2003), beginning with his "epic" Dog Star Man (1961-64), used patches of willfully scratched and altered emulsions and then, after a certain point, hand-painted frames almost exclusively.

When I first saw Decasia, I thought I'd better look at Brakhage again. Morrison studied animation, but his film is more like films in the experimental tradition than Fantasia. So I suffered once more through Window Water Baby Moving (1959). An actual childbirth! The father present! It is instead the restless camera and the off-kilter framing, the superimpositions and speed-shots that make it still worth seeing.

Dog Star Man (Brakhage and his family alone in the Colorado mountains) has its moments too, but whatever you do skip the Brakhage interview on the disk. It will ruin Dog Star Man forever. The tree he is seen chopping is supposed to be the Nordic tree of life. Sorry, Stan, the stories you told yourself are not the story this film tells.

Brakhage seemed determined to indulge in beatnik twaddle. Let's just say it was the times that made him do it. Defense of even semiabstraction and of ruptured narrative had to take the form of smarmy mythmaking. I much prefer this quote from his book Metaphors on Vision:

Imagine an eye unruled by man-made laws of perspective, an eye unprejudiced by compositional logic, an eye which does not respond to the name of everything but which must know each object encountered in life through an adventure of perception.

The truth is that as Brakhage moved from antinarrative structuring of buried narratives and the quasi-documentary to total abstraction, he got better and better. The three-minute Mothlight of 1963 is the real breakthrough film, a kind of waltz of moth wings. From then on, it is an endless string of brilliant films. However, he couldn't break from fancied story-telling or beat generation gestures towards poetry. Like all good DVDs, By Brakhage has "extras," in this case the filmmaker talking about his work. Approach with caution. Don't listen to what he thought he was doing when he made The Dante Quartet (1987).

Forget Dante, just look at the film. It's made up of handpainted frames that obliterate the underling photographic images. It's like seeing a thousand and one abstract expressionist paintings, pixilated. Of course, with a DVD you can stop the action and see it frame by frame. The individual images are most often held for two or three frames. Thereby, surprisingly, it is revealed that in fact the individual handpainted frames would really not make great paintings. What is important -- surprise! -- is how they move from one to the next, in a great balance between single image and persistence of vision. The latter of course is the trick of movies that makes the images seem to move.

For discussion further along the road:

Is there an appreciable aesthetic difference between moving pictures projected floor-to-ceiling on gallery or museum walls and those projected in movie theaters, on a screen with everyone sitting face-forward, eating popcorn? Is there a difference between either of these and watching a movie at home on a video monitor? Would new art star Douglas Gordon's brilliant, super slow-motion24-Hour Psycho or his superimposition of The Song of Bernadette and The Exorcist work on your TV? Is the future of "underground cinema" (i.e., the art movie) the DVD? Will the DVD and the download future revive or further undermine the underground? If the "underground film" has been absorbed by the art world's embrace of projected installations, how do we explain the above-ground distribution of Gus Van Sant's Psycho and Gerry and Mike Figgis' four-screen, real-time Timecode? Or even Christopher Nolan's backwards narrative Momento? Can there be a new post-post-Structuralist , post-Deconstructionist view of cinema that includes more "experimental" films as well as mass-market ones? Can we put the baby back in the bath?

AJ Ads

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Exploring Orchestras w/ Henry Fogel

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary

Tyler Green's modern & contemporary art blog