main: February 2004 Archives

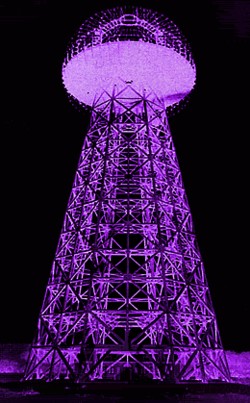

Nikola Tesla'sPowerTransmission Tower

The Future of Opera

In another life as an arts administrator -- once my "day job," as theater people say -- whenever myassistant felt she might have exceeded her brief, she'd preface her confession with the phrase "just so you know." For example: "Just so you know, I have paid Consolidated Edison rather than Verizon." To this day she does not know that I came to dread the phrase. But sometimes it comes in handy. So...

Just so you know, I have written about music in an art context before and maintain that it is not always as separate from the visual arts as the tradition-bound may maintain, Gotthold Lessing and his lesser followers be hanged. Each art does not have to be true to itself.

The first piece I ever wrote for the Village Voice as an art critic in the '60s was about Meredith Monk, the now-famous choreographer, dancer, composer, vocalist and mixed-media artist. Later I wrote about La Monte Young -- post-Cage pioneer minimalist composer. Most people have not yet caught up with him because he refuses to release the tapes of his influential, droning and eardrum-bursting Theater of Eternal Music, created and performed with Marian Zazeela (who also provided projected mandala visuals), pre-Velvet Underground John Cale, Tony Conrad, and Jon Gibson, whom we will come to later. The sound of the endless and still-unfinished piece called The Tortoise, His Dreams and Journeys (1964- ) was so loud that entering the small auditorium where it had already begun behind closed doors was like walking into a hot swimming pool. (I was first exposed to Young's music in San Francisco in 1961 at avant-gardist Ann Halprin's dance deck; we young poets, Joe Ceravalo and myself, had met him through poet Diane Wakoski. He was more or less the composer in residence: burn a violin, set some butterflies loose in a concert hall, etc. But he also played a mean sax.)

A bit later I myself performed in a music piece by poet Jackson MacLow in Yoko Ono's pre-Beatles loft. As a performance artist, I "choreographed" a solo to music from Swan Lake and constructed the music for my projected theater piece called Lower Forces, in which the audience read the script from the screen rather than seeing anything actually performed.

As any student of art must now know, painting and sculpture have not always been practiced in isolation. We can point to the Futurist andDada artists and poets for interdisciplinary cross-fertilization and for examples of -- perish the thought -- theater and, even more shocking, music. John Cage, our hero, clinched the deal and in the process inspired Happenings, Fluxus Events, Performance art and other forms of mixed-media theater, some of which might as well be called "operas."

Although most significance shifts in form are collective, at this point it looks as if we can give some credit to La Monte Young for minimalism in music, at its most extreme. Philip Glass, whom I first heard performing in an art gallery under the enthusiastic patronage of minimal artist Sol LeWitt, and even Steve Reich -- both of whom we like -- seem crowd-pleasing in comparison. (More recently, we like Phil Kline's Silent Night, his famous boombox piece, heard Christmastime in Philadelphia again and at other sites around the nation, and certainly his Zippo Songs, with texts derived from messages scratched on cigarette lighters in Vietnam.)

This brings us to Jon Gibson, whose work as a composer is within the minimalist style. He's now composed a one-act opera with a libretto by Miriam Seidel who, like myself, is a bit of a polymath. She is a writer, dance critic, sometime art critic, and has and plays a theremin. You know what a theremin is. Think Bernard Hermann's great music for The Day the Earth Stood Still. You wave your arms in the air and a single line of music slides and trembles in eerie ways. Or happy ways, if you think of "Good Vibrations" by the Beach Boys.

But Seidel's brand-new opera, called Violet Fire, does not have a theremin in sight. Although Leon Theremin's life might also make a good opera (after his success with his musical instrument in the U.S. he was kidnapped by the K.B.G. and brought back to the U.S.S.R.), Violet Fire is instead all about the scientific genius Nikola Tesla. I saw it recently in Philadelphia, where it was performed for two evenings at Temple University. Billed as a multimedia opera, it is very visual indeed, and as a minimalist music fan and a Tesla fan, I have no choice. I just have to write about it.

I am interested in opera. I backed into this most collaborative and interdisciplinary form because of my love of Baroque and contemporary music. One of the peak experiences of my adolescence was suddenly being able to hear simultaneously the various voices in a Bach Brandenburg Concerto and then learning one could do that too with Bop. So, to make a long story short, after hearing Philip Glass operas -- and learning that jazz and Baroque music are not only both polyphonic but also employ improvisation -- we expanded by listening to Monteverdi, Lully and Rameau, and then Handel and, yes, Vivaldi and ever forward in time.

John Cage once said that all you had to do to make something interesting was to have at least five things going on at once. So, surprise, what traditional art form has five things or more going for it all at once? Words + sound + people singing + people moving around + painted stage sets = opera. Opera, impure, glorious opera, Walt Whitman's favorite form ofentertainment.

* * *

Three days after seeing the American premiere of Heinrich Sutermeister's marvelously complex The Black Widow (1935) at the Harry de Jur Playhouse in Manhattan's Lower East Side, I made my way to Philadelphia to see the first public performance of Violet Fire, another one-act opera. There is something fetching about one-act chamber operas: the spell is not broken by a trek to the lobby and all the fuss that entails.

But I wonder if multimedia opera is the wave of the future. I did not see Steve Reich's The Cave, but have heard it without the multimedia accoutrements it requires. I have looked at and enjoyed his Three Tales, now in a DVD and CD package, the former with visuals and better sound. The Black Widow, performed by the Gotham Chamber Opera, skillfully used film and image projections. Violet Fire has multiple projections too. How else can you sing the story of Tesla?

Nikola Tesla was the man from Croatia who invented alternating current, tamed Niagara Falls, invented the power grid, was cheated by both Westinghouse and Edison, had a plan for a Star Wars defense system and a death ray that would ensure world peace, seemed to have contact with extraterrestrials (or according to some was an extraterrestrial himself) and, best of all, was convinced he could provide and wirelessly transmit electricity free to all. Newspaper headlines, period photos, computer-generated images of his power tower collapsing, pigeons whirling, dynamos and diagrams and two very real Tesla coils all needed to be seen. Or as this opera proves and as Tesla sings: "Perhaps I was a little / Premature, perhaps / Too far ahead of time." The surprise for me is not that Seidel's libretto bounces around in time -- adding to the Tesla man-outside-of-time theme -- but that it is poetry.

Gibson's lovely, efficient, and sometimes even beguilingly astringent music was played onstage by Philadelphia's Relâche Ensemble. I haven't heard much of Gibson's music before, aside from a few things on WNYC radio's New Music venue. He's is one of the founding members of the Philip Glass Ensemble, so minimalism could have been predicted. There's just enough minimalist churning to suggest electric dynamos, but no predictable Phil Glass crescendos. The vocal writing is surprisingly beautiful. I was thrilled.

But on with the plot: Tesla, although routinely hounded by the press for predictions of things-to-come, was deadly poor at the end. He lived alone in a hotel room, his only joy the daily feeding of pigeons in the park. A white pigeon was one of his favorites and, of course, functions as the symbol of the mystical, blinding light he seems to have experienced. Here I would have preferred a literal blinding light rather than the Isadora Duncanesque dancing that just seemed to get in the way of both the high tension, as it were, and the restrained, allegorical, multimedia pageantry. Violet Fire, like Glass operas and the preludes to French Baroque operas, is a moral pageant: virtue arguing with beauty, truth with form. But in this case the argument is between science-as-poetry against commerce and doom.

I wouldn't have had a real problem with the union of Tesla and the symbolic white dove/dancer at the end, walking off like bride and groom, if the staging, the acting or direction had not made it seem that the dancer in the ivory tunic was Tesla's ideal woman. From reading several Tesla biographies, it really doesn't seem he had any ideal woman in mind. Or man, for that matter. He really was a stranger in a strange land -- or, asthe following made-up conversation attests, a kind of saint.

"But don't you see? The White Dove is the Shekhina, the feminine aspect of God that accompanied Israel in exile," a friend explained, outside in the lobby.

"Tesla wasn't Jewish," another friend interrupted.

"The author is and I am," replied my friend. "In any case, you don't have to be literally Jewish to be one of God's chosen people."

"Maybe he just mystically unified his masculine and feminine aspects," volunteered someone standing nearby.

This is another way of saying that the best thing about Seidel's libretto is that Tesla, one of the world's greatest loners, is left as he was: a mystery to all.

Other things I learned:

Like all the operas I really enjoy, Violet Fire has a lot of subtext. Fortunately, words supported by engaging music give you time to think about what's going on in a way that most theater and all but the slowest of films do not. Any story is only as good as its subtext. The subtext is unspoken; the subtext is the real meaning of the text or the action and is usually more complex that discursive language will allow. Actors will know what I mean.

Vis-a-vis acting, the great thing about opera -- when divas are kept under control -- is that the music replaces most of the arm-waving and face-pulling usually required by nonmusical drama.

And what next? The multimedia effects essential to Violet Fire mean it can be presented in many different kinds of venues. Expanding these effects would make Brooklyn's BAM a natural. But if not BAM, then why not the charming and fully restored turn-of-the century Harry de Jur Playhouse at the Henry Street Settlement in New York? And why not a nicely produced DVD?

Old City Gallery Hop

Old City in Philadelphia, down by the Delaware waterfront and around the Benjamin Franklin Bridge, offers a significant, small-city cluster of galleries. Here are a few of the "bests" resulting from my walk:

David Goerk at Larry Becker (43 N. 2nd St., to March 30) shows small paintings cum wall sculptures, in which various geometrical forms -- and some irregular circles -- jut off the wall and are faced with encaustic. Some of my favorites were the all-white Double White (a six-section grid), White Yellow White (three rectangles in a vertical, the yellow one at the center), and 6 x 4 (a red geometric with a slanted upper edge). All the works have a frontal, but very cool, painterly interest, and sidewise a sculptural gesture in layers of wood and gesso. Although none was larger than the largest at 11 inches high, I had the feeling that they could hold even much larger walls than the ones here.

Temple Gallery, a project of Tyler School of Art/ Temple University, has "analog click click" (at 45 N. 2nd St., to March 6), a group show on the theme of digital technology in art. We have seen Carl Fudge's semipattern paintings in N.Y. before, and Lia Cook's computer-based, realist weavings are known too. New to me and promising is a wall piece (Blotch) by Cindy Poorbaugh and the ceramic sculpture and digital drawings by Mark Lueder. Lueder works out his forms on the computer and then constructs them of clay. The ceramic piece by itself is credible enough, but in conjunction with the computer printout it zings.

Speaking of ceramics, at The Clay Studio (139 N. 2nd St., closed Feb. 15) Denise Pelletier's hanging installation called Mute was hardly mute. A suspended grid with a concave indentation, it was made up of hundreds of black, hand-made, invalid feeders ("sick cups") fashioned out of sanitary porcelain when the artist was in residency at the Kohler Company in Sheboygan.

Very beautiful and slightly strange too -- strange is good --are Keiko Miyamori's tree rubbings at the Community Gallery, Nexus Foundation (137 N. 2nd St., to Feb. 28). Each framed rubbing is titled after the Philadelphia location of the tree involved. Beneath each, for this incarnation, is a little shelf with a harmonica covered with a similar rubbing. Two keyboards on opposite sides of the room and a prism at the center complete the installation, but it is the rubbings that are most winning and could indeed stand very poetically on their own.

Finally, I also liked Laurie Reid's water-altered white paper "drawings" (?) at Gallery Joe (302 Arch St., to March 13). Barely marked or inflected, they are subtle reliefs, as much as drawings or works on paper. They are the paper.

Note: Yours truly, the polymath and founder of Artopia, will be showing "Seascapes & Mended Stones" at 473 Broadway Gallery in N.Y. from March 2 to 13. Reception: Thursday, March 4, 6-8 p.m. Briefly, these are petroleum-impregnated beach sand on found paintings and painted plywood, along with a floor-piece made of broken and glued-back-together beach stones. Intrigued? Check out my website underPerreault's art.

Complaints will not be a constant theme, for their impact is diminished by frequency. Besides, I am, as friends and even enemies will testify, even-tempered and not quick to complain. But sometimes you just can't hold it in.

Poodle poop in the Chelsea art district is an increasing blight. If you are going to live in that trendy neighborhood with a Comme des Garcons store as your only haberdashery, do as others must do: scoop the poop. I don't know if you live in Chelsea (more and more do) or you just bring your poodle to work because after all, sitting in a gallery can be a lonely job, but you know who you are. Until spring comes - if it does indeed arrive - it's easy enough for a visitors like myself to kick the little pellets off the icy walks, but once the weather changes there will be treachery afoot.

Worse yet is cellphone blight. I am a cellphone user myself, when I remember to stick it in my pocket, as in "phone-booth-in-your-pocket." I never use my cellphone in my car. It's against the law I'm told, but as a pedestrian I am used to nearly being run over by one-armed drivers. I might at some point attempt a citizen's arrest.

I am also used to couples holding hands as they walk, their outside hands clamping cellphones to their outside ears and, yes, they are talking to their phones and not to each other. Or maybe they are talking to each other, using their cells as a distancing device. If they are in Chelsea they inevitably step right on rather than over the poodle poop. In case you wondered, this is why galleries have polished cement for floors rather than wood or wool.

As a naturally curious person, I really want to know what everyone is talking about as they walk the streets. Judging from Amtrak and Long Island Railroad experience, such important issues as 1% or 2% milk are under debate.

But what I am not used to and will never get used to is cellphone conversations in art galleries. Recently, a young lady one Saturday let everyone in the gallery know all of her evening plans. She and whomever she was shouting to decided on Mystic River rather than Cold Mountain. They chose when and where and even what to eat: pizza pie. She did indeed say "pizza pie." Some of us, believe it or not, were not interested, as she marched around with her cellphone and her Day-Runner, demonstrating a bad case of what I call the-world-is-my-living-room syndrome. We were trying to watch and listen to a videotape, but if the truth be known, her impolite and soon to be illegal behavior would have been rage-inducing even if we had only been trying to look at a painting.

The next week I noticed a "No Cellphones" sign at O.K. Harris in Soho. I hope it spreads to other galleries. In Artopia we confiscate cellphones at the door and melt them in the back room. But only after stripping the auto-dial numbers, later to be used for obscene phone calls claiming to come from their owners.

And in museums? Since Audio-Guides seem to be required, there's no room for rude and soon-to-be-illegal cellphone usage. Museums have other problems. Can I mention stupid wall texts and messy toilets?

Madness at the Met

I made the big mistake of going to the Metropolitan Museum of Art to see "Playing with Fire: European Terra-Cotta Models, 1740-1840." Why? A thousand times I ask myself why, why on earth was I lured into such a mind-numbing adventure? Well, I like clay. Sadly, only three or four of the fired clay figurines are rough enough to be expressive and worth looking at.

The little terra-cotta statues - some of them quite ornate - are mainly models for marble sculptures or sometimes bronze monuments. Some, it's true, are the demonstrations of skill once required by various art academies or, perish the thought, works in themselves.

Other than the often noted truism that the bigger the banner over the entranceway, the more trivial the show inside, there are four things this exhibition proves:

1. Bad taste is eternal. No amount of art-historical detective work can justify this honorific display of pseudo-art. If you hate academic sculpture, as I do, you are really going to hate these banal studies.

2. In her neat piece in the N.Y.Times, Grace Glueck let it slip there is now a growing market for this fancywork. Could the Met's inflated display of mostly pointless scholarship be market-driven? Just because it no doubt cost huge amounts of time and money and academic energy to track down these dainty exercises in bad taste does not mean they are worth looking at. Or buying.

3. There is a reason why we like Rodin more than what went on before. There is a reason for modernism too: academic terra-cotta figurines.

4. People, whether of the time these allegorical whimsies were made or even shockingly in the present day, will gladly look at art as long it shows naked breasts and bare butts. What we have is culturally sanctified soft -porn.

Then I made an even bigger mistake, I stopped off to see a small exhibition called "Significant Objects from the Modern Design Collection." The wall text says "Industrial design is a recent area of collection for the Metropolitan Museum of Art." Is this really true? I seem to remember seeing some spectacular photographs from the Thirties that documented the exhibition of an office by Raymond Loewy. Institutional history gets buried along with everything else. If the Met did not collect industrial design, it certainly exhibited it.

In any case, the current offering is the usual hodge-podge. Of course, you can't go wrong with a little radio by Phillipe Starck. Or a famous Memphis bookcase by Ettore Sottsass.

Then, turning a corner, what did I see? A sculpture by Harvey Littleton: Amber Bust, 1976. What? Because the Littleton is made of glass, does that make it industrial design? Even worse, next to it is a wallpiece by Michael Aschenbrenner, his emotionally powerful Damaged Bone Series from 1990. Inspired by the artist's experiences in Vietnam, it is composed of glass "bones" combined with various other media. It looks like sculpture, it feels like sculpture, it was made as sculpture, and the collector who donated it bought it thinking it was sculpture. But here it is proudly displayed in the context of industrial design. Clearly it was not machine-made and was not mass-produced and it is certainly not functional. Are the Met's departmental categories so rigid and out of date that a mistake like this was allowed to happen? What can the public make of it?

Like most omnibus museums based upon an academic template, the Metropolitan has only a decorative arts department and not a craft department, which, because glass is used here, might embrace these orphan works. Surely a craft department would have its own problems. (I don't have the time or the patience to go through that again.) But putting these two works in what purports to be a display of industrial design from the permanent collection, no matter what the departmental fiefdoms backstage, is ludicrous. It is insulting to the artists and to the public.

Marc Quinn, Helen Smith, 2000

When you first walk into the gallery, you will probably be attracted to the smooth, white marble and the semblance of sensuous flesh. How hard, white stone became associated with the softness of the body has to do with illusionism and cultural conditioning. That polished marble still signals art with a capital A is further evidence -- evidence you can feel -- that the mind as well as the eye plays tricks on the heart. That Greek statues were originally painted is neither here nor there. Facts are not important; convention is what counts.

Marble short-circuits modesty. We are allowed to look at what purports to be the naked body. Of course, through the very nature of the material and the carving and polishing, hair and pimples have gone away, raising high expectations for real-life nudes, never as comely, mathematically curvaceous or muscular as those stone gods and goddesses or elder statesmen.

But wait a minute. The missing limbs you first thought were just the results of ancient wear and tear are the missing limbs of the subjects. The rounded, truncated parts tell us that. Because we connect in a prelogical way with depictions of the human form, we ourselves suddenly feel physically challenged. Empathy and voyeurism are confused.

Yes, Marc Quinn's statues are shocking. Perhaps this is why no commentary I have yet seen about Quinn's depictions has grappled with their status as sculpture. Although the current exhibition at Mary Boone (54 W. 24 St., to Feb. 26) is the first U.S. showing, works from the Quinn's controversial series were first displayed in Europe as long as five years ago.

Minimalism in sculpture -- exemplified by Sol LeWitt's three-dimensional work, Donald Judd's boxes, and prime Robert Morris geometries -- can be seen as an effort to thwart empathetic projections of body image upon inert matter in order to make truly abstract sculpture or "specific objects." In this way the normal operative of three-dimensional art was destroyed or, at the very least, illuminated. It might be informative to see Quinn's statues as a related ploy.

On the other hand, in Quinn's case the sculptural or antisculptural is not the point; the content is. Or I could say it is the disruption between the artist's stated intentions and the feelings, aesthetic and otherwise, these difficult works may cause. Quinn has indicated he wants to honor people with corporal disabilities by casting them in the heroic mold of the tradition of the idealized human form, as expressed through marble. Each statue comes with the full name of the model.

"It's more about looking at something, and what you bring to it from your knowledge of the context of art. And so, what is acceptable and aesthetic in art is very shocking and different in real life," said the artist in an April 2000 Sculpture Magazine interview. "I was in the British Museum, and I thought, 'If you took these [marble sculptures, many of them missing limbs] literally, what would the modern versions look like?' But the sculptures are also celebrations of the sitters -- they are heroic sculptures of these disabled athletes."

From this assertion we learn something not evident in the exhibition itself. The models are athletes. We can assume they are used to being looked at in real life, and we may not feel so squeamish about our gaze. In real life we are not supposed to stare at unusual people.

Is there any expressiveness or emotion offered here? Focusing on the five images on the Mary Boone website, I'd say that Selma Mustajbasic is pensive or bemused; Stuart Penn offers a pugilistic pose; Tom Yendell has a stout presence; Helen Smith is almost delicate. Kiss, the only one without the model names, is chaste. But on the whole, abstract sculptures by Jean Arp say more about the body than these more-or-less Victorian figures. Flesh is not the point.

Quinn started with life casts, then had them realized in marble at full-scale by professional carvers. This effectively divorces the work from any artist craft- or skill traditions and more important, produces smooth, impersonal statues. Since the subject matter is tough for most viewers, perhaps this is necessary, yet one suspects that the distancing has more to do with style than delicacy of feeling, and with emphasizing the conceptualism of it all. After all, this is the artist who showed a self-portrait of himself carved in his own frozen blood in the "Sensation" show in 1997 at the Royal Academy in London. ("Sensation" later caused a ruckus at the Brooklyn Museum, but for the wrong reasons.)

This is not the place to rake over those old coals, but certainly it helps to know that Quinn is generally considered to be part of the Brit Pack, along with Damien Hirst. Like Hirst -- and Jeff Koons, our nearest U.S. equivalent -- Quinn is uneven. But when he hits, he hits real strong. He is considerably less sunny than Koons and perhaps less expansive than Hirst, but on the strength of the marble statues, I'd say he's an artist we will continue to contend with. Sharks in tanks; floral puppies; missing limbs. Quinn has less taste.

Quinn's marbles are not sculpture in any modernist sense. It may be surprising to read that I do not think all Greek or Roman statues are sculptures, either. Sometimes they are, but mostly they simply embody ideals and are boring formally. When statues that attempt to communicate (or impose) civic or religious ideas are also sculpturally expressive, then we really have something important. But how rare, how rare indeed, that is.

By mimicking the forms and formats of the Greco-Roman, Renaissance and neo-Classical presentation of ideal body types, but presenting bodies that have missing parts, Quinn is criticizing the idea of the ideal human body. In doing so, he slams vanity and gym culture, while celebrating the bravery of those who through birth or accident cannot achieve the historical and cultural fantasy.

Yet one cannot entirely avoid the voyeurism involved.

No doubt, Quinn is contesting beauty. Still, many will see Quinn's statues as sensational: that is, willfully controversial and provocative. He is doing both, and the real strength of the work is the problem of the artist's sincerity. Sincerity, thanks to Victorian cheap-sentiment, is one of those modern and postmodern taboos. Sincerity, like intention, can't be seen. The artist's own concept of or desire for sincerity, or the viewer's "perception" of such, cannot count. In real life, sincerity is proved by actions, but in art there is no similar test.

The Art Couple

When an established artist becomes an artist couple, what does this mean? Does the work change? Why is it always the wife who gets added on to the famous husband's career, and there's not one husband appended to a woman's?

The Soviet/post-Soviet "conceptual" artist Ilya Kabakov and his wife Emilia are now publicly a husband-and-wife team. They join the illustrious ranks of the late Ed Kienholz and Nancy Reddin Kienholz; Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen; Christo and Jeanne-Claude.

Although it might be an interesting study, we are not considering Newton and Helen Harrison, who have always been a team, as have Gilbert and George. The latter are British, and as far as we know are rather like Gilbert and Sullivan, only more so: not married to each other in any sense of the word. Furthermore, we can'tput those other Soviet/post-Soviet conceptualists, Kolmar and Melamid, in any matrimonial boat. I also know two brothers, Einar and Jamexde la Torre, working in glass-based assemblage, who function as a team but, unlike the others mentioned, also make art under separate signatures.

In the case of the Kabakovs, the Oldenburgs, the Christos, and, before them, the Kienholzs, the partnership came well on into the husband's career, probably to acknowledge the ongoing contributions of the wife and, I would venture to guess, to make ownership, copyright and possession of artworks airtight. But who knows what darkness or devotion lurks in the congruently beating hearts of couples -- of any persuasion. As far as I am concerned, anything that contests the hegemony of single-person authorship and gives someone his or her fair due is a step in the right direction.

Furthermore, I have observed that artworks may change when studio assistants change, and that often the artist is more like the auteur/movie director than the sole agent.

Perhaps every artwork should have the label equivalent of a movie crawl. Carpentry, welding, prep-work, lighting,color mixing, photography, and the writing of didactic statements should all be credited. Preliminary drawings or digital work also require some acknowledgement. And how about a nod tothe hidden world of secretaries, bookkeepers, and just plain gofers?

In any case, here's an assignment for some future graduate student: in all four cases of the married art couples cited above, did the work change after the double byline emerged?

As a start, we now know Ilya and Emilia Kabakov have been working together since 1989. She too endured life in the U.S.S.R. A graduate of the Moscow Music Conservatory, she later made her way to the West.The Kabakovs have lived in New York since 1992. Ilya made installations before as well as after 1989.

Looking through the documentation in Amei Wallach's Ilya Kabakov: The Man Who Never Threw Anything Away (Abrams, 1996), I can see a sort of zigzag progression from language-laden and intentionally cluttered works to this year's The Empty Museum at the SculptureCenter (44-19 Purves St., Long Island City, to April 11).

This oddly spectacular new installation can be classed with, and may be an outgrowth of, Kabakov's Incident at the Museum, or Water Music (1992) or The Life of Flies of the same year, which represented "a series of halls in a scholarly provincial Soviet museum that receives few visitors." Incident at the Museum, which was at the Feldman Gallery in New York, displayed fake paintings by a "re-discovered" Russian modernist by the name of Stepan Yakovlevich Koshelev and looked extremely convincing. The flash-point however is that there were buckets and tarps everywhere and water dripping from the ceiling. In The Empty Museum, there is no water. In fact, there are no paintings, only spotlights on the deep red walls.

If Kabakov's wife has influenced him to move beyond thesomewhatcluttered and "literary" installations of the past, she surely shouldbe applauded. It is not that I have anything against smudging the border between art and literature. I just don't like it when there's so muchnarrative that I yearn for a book rather than an exhibition. You might say that Kabakov has -- rather, the Kabakovs have -- stopped being a novelist (a mixture of Dostoyevsky and Kafka) and become a poet.

This grammatical awkwardness through which we have just passed is another reason why art coupledom is resisted. Language balks.

The Empty Museum takes up nearly the entirety of the SculptureCenter space. You see the metal studs and wallboard construction all around the outside of the built room. I find this satisfying in a sculptural way, just as I have always preferred the photos of Glen Seator's 1999 Check Cashing Store that show the gallery side rather than the street side of that jolting replica (see my Seator essay). From the street, the work looked so real that some people tried to get inside to cash checks, whereas from the gallery it was all beams and wallboard. I like seeing how things are made, which is my traditional, pro-sculpture side. Of course, installations are usually lumped with sculpture, prompting me to define sculpture as anything that is not painting.

Actually, the first thing you see of The Empty Museum is a door ajar. It doesn't open beyond a certain point, so you have to edge your way in, where, embraced by Bach's Passacaglia, you can rest on the Victorian seating in the middle of the room and contemplate … nothing. Well, not exactly nothing. You can meditate upon the spotlights. You can gaze upon moldings or on the two sealed exit doors. You contemplate the absence of paintings and what that might mean. The Kabakovs finally let you make up your own story and your own meanings. Here are some of mine:

The paintings have been removed because they are on loan to some casino in Las Vegas; because they were recently discovered as fakes; because war has broken out and they are in storage for safe-keeping. They have been removed because suddenly it has been discovered paintings are not art. Or, to the contrary, they were too controversial and excited the museum-goers to weird sexual acts, revolution, sabotage, and sudden bouts of lethargy.

Or -- and this is my favorite -- the paintings were not removed:they merely steadily diminished in size. The huge numbers of people looking at them day after day robbed them of their auras and they shrank to nothing. Or maybe they disappearedbecause not enough people were looking at them. People make auras, infuse objects with mana.

So, after all, The Empty Museum is not really like Yves Klein's notorious empty gallery of 1958 (Le Vide/The Void). That great French mystic was trying to exhibit the Void or Nothingness, rather than nothing. The Kabakovs are a bit more down to earth. They offer a "Total Installation," meaning an artwork you step inside of and thereby enter another world. This new world is one where paintings simply -- or not so simply -- disappear, have disappeared. I smell a kind of nostalgia.

Or is The Empty Museum antinostalgia? A certain very powerful wing of the art world has an overwhelming nostalgia for painting, so overwhelming that really bad painting is embraced just for the sake of upholding painting. Then too I also like that The Empty Museum, a work about painting as it is institutionalized, is in a sculpture space. Is there a painting space that can return the favor?

* * *

Also at SculptureCenter is a group exhibition called "In Practice." Highlights are Nicolas Dumit Estevez's hilarious Toilet Training, a sound piece for both the men's and women's restrooms. A woman's voice, somewhat like the moving sidewalk voice at various airline hubs, instructs you on proper use of the facilities.

On the Lower Level (i.e., the basement), Karin Waisman's beautiful Patience consists of four neatly made, full-size, white paper chairs inflected with meticulously cut-out lacelike areas, the debris left on the floor. I certainly liked Juliane Stiegele's Skyline, which coincidentally also uses paper. It's a video that shows paper skyscrapers moving about and then for the most part collapsing. They are attached to live snails: 42 snails were used in the three-hour 56-minute production, here edited down to 11 tasty minutes.

I love art in odd places. Consider, for instance, various stabs at using P.S.1's funky basements and attics. I'd like to see MoMA itself and the Whitney let a few artists tackle presently out-of-sight, backstage spots.

Because the SculptureCenter building was once a trolley repair shop, the piece that best uses the actual space is Karyn Olivier's evocative Ridgewood Line (BQT Ghost NO. 6064). Train tracks are imbedded in the floor of one of the long arched alcoves

Outside: You shouldn't miss Stephanie Diamond's billboard on the roof of the building. You have to walk to the nearby Thomson Avenue Bridge to see it, but there are clear instructions at the front desk. The title is These Are the Men Who Hit on Me on the Street (Buenas Tardes). The artist, using a disposable or point-and-shoot camera,captures the culprits who harass her and then makes billboards out of the images. Buenas Tardes shows a man "hitting on her" from his car.

AJ Ads

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Exploring Orchestras w/ Henry Fogel

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary

Tyler Green's modern & contemporary art blog