Artopia: May 2009 Archives

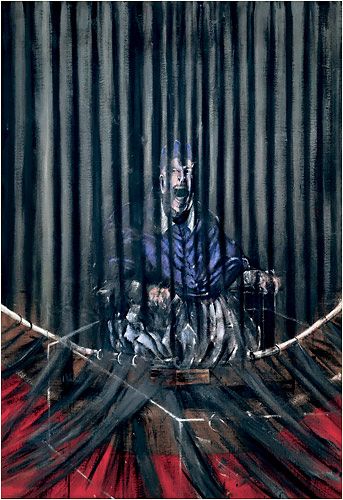

Francis Bacon, Painting, 1946

Bacon Fat

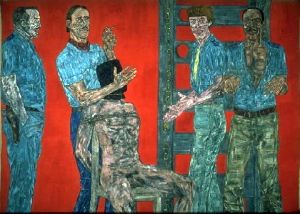

When it comes to Francis Bacon (1909-1992), less is more. The current "Centenary Retrospective" at the Metropolitan, on view through Aug. 16, is ample proof. One picture at a time can be quite effective, but seeing any Bacon that once might have taken your fancy (perhaps out of some deep-seated perversity) along with others of the same or far too similar ilk destroys any credence he might once have had as a major artist.

A deep appreciation of Bacon's fat is greatly helped if you are 13. That was probably when I myself saw a reproduction of his famous Painting, 1946, owned by the Museum of Modern Art: the side of beef, the open umbrella, the mouth full of teeth, the microphones. And later I saw, in other paintings, nude men doing unmentionable and possibly erotic things to each other. Were the figures taken from Muybridge's blatant studies of scantily clad male wrestlers? Of course. That made them even more naughty. Back then there was nothing worse than copying from photographs. Hmm. No, there was something worse: copying other artists. Bacon's major inspiration was midcareer Picasso, all bloated body parts and sometimes screaming mouths. And Bacon did copy Velázquez.

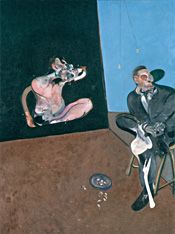

Bacon's screaming Velázquez popes? Anyone growing up gay in the '50s had good reason to hate the church, even if one had not been molested by the parish priest. Surprisingly, Bacon tried to deny that his work was in any way autobiographical. He denied personal expression. He denied story-telling. In art, loud and frequent denials are sometimes proof. During his checkered life, our artist of the moment -- now brought back from the dead -- stopped one biography from being published; but he was not above exploiting notoriety for career's sake. Bacon tried to have it both ways.

The love of his life, the chunky George Dyer, was a thief, and Bacon loved to say that he first met him when he caught him robbing his apartment. He painted Dyer over and over, for, you see, the artist had discovered early on that the best insurance against blackmail was to be truthful to all about his personal life. Or personal lives.

Nevertheless, in 1977 Bacon stopped the publication of what was to be Michael Peppiatt's Francis Bacon, Anatomy of an Enigma, finally published in 1996. "As with several other projects to which Bacon initially lent his support," writes Peppiatt, "he drew back at the last moment, fearful -- for all his recklessness -- of revealing 'too much' about his life." It is my main source here.

Minus all the tedious art-world details and descriptions of the art, the book could be made into a movie, a horror movie.

Bacon: Study After Velázquez, 1950

Where's the Bacon?

If only I could like the paintings. If only I could be 13 again. And anguished. But contrary to the rule in most fiction, I wasn't anguished about my sexuality. Even I knew that the self-punishing homosexual was a self-hating, self-indulgent, literary invention by Proust, Gide, and yes, even Genet. Was I the only one who had read Walt Whitman? I was anguished because, down on the farm, I could not get any. I wanted love. I wanted action. Not torture and slabs of meat.

If Bacon's paintings are really about anguish in general and not about homo-anguish in particular, then I can live with them. Otherwise, they stand to confirm a demeaning text: gay men are not men, they are guilt personified.

So do we delight in the fact that Bacon let it slip that he liked to wear women's underwear? That he had a collection of twelve Rhino whips? Yes, we do. And we sort of wish these facts were on the Met's august walls. Instead, one text actually suggests that the paintings, done by an avowed atheist, are what the world looks like without God. Viewers stand in front of this so-scholarly assertion looking puzzled.

It would be more accurate to say that the paintings are what the world looks like without art criticism. Bacon let it be known that he destroyed a lot of his own paintings, apparently as part of his down-to-the-line studio practice. If nothing else, this exhibitions proves he did not destroy enough.

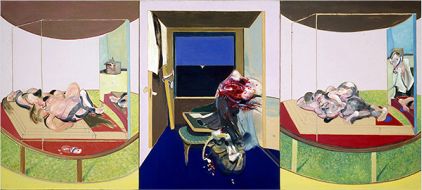

Bacon: Three Studies for a Crucifixion, 1962

BLT (Blatant Lascivious Teasing)

But I want more details on those wall texts. I want to know if Bacon liked wearing bras or panties or both? How British. And in terms of what was once called the English Vice, I want to know who was handling those whips, exactly what was being done with them, and how often. That would be more interesting than the proclamation of Bacon's atheism. After all, technically speaking, Buddhist too are atheists.

But please, if a new wall text goes up detailing Bacon's sexual fun and games, I would urge that it be spelled out that, at least in Great Britain, more heterosexual men wear bras and panties and use whips than gay men do.

Why was Bacon so over the top? Surely, if you are treated like a criminal, you will act like one. Bacon operated largely during a time when homosex could result in life imprisonment even if you were already in prison. (And before that, the gallows.) If you have everything to lose, than what the hell? This may explain some of Bacon's carryings on: gambling, rent sex, lipstick and dyed hair, and sex with his uncle -- in Berlin, where said uncle was supposed to make a man of him. This was set up by Papa Bacon, soldier, horse-breeder and man's man.

Papa Bacon simply could not understand why Baby Bacon broke out in a horrendous, possibly life-threatening asthma attack every time a dog came near or when he was forced to visit his father's much-cherished stables.

Francis Bacon, Untitled Rug, 1929 (not in exhibition).

Francis Bacon, Untitled Rug, 1929 (not in exhibition).

I assure you, we are not. Some of us are even married -- to other men, at long last, much to the relief of the guardians of house and home and much to the profit of the matrimony industry.

Two Studies for a Portrait of George Dyer, 1968

Although yours truly in his youth also had a second-storeyman as a lover (this is true), it was only briefly. Bacon kept George on for years, declaring him the most handsome man he had ever met and made him pose for the photos that became the paintings now so celebrated for their "anguish." Poor George. Judging by the paintings, he earned his keep, then died of an overdose. Tellingly, the run of portraits that proliferated after George was out of the picture are simply not as good: horror for hire, bread-and-butter bunk.

But more about Bacon's childhood, if you can stand it. In some sense, his childhood lasted all of his life.

The Nanny

Not only did Papa Bacon throw Baby Bacon out of the Bacon Irish Manor House when he was a mere teen, Mama Bacon didn't like him much either, telling him he was so ugly no one would ever like him. He was indeed a pie-face. Photographs do not lie. Possibly in revenge, he later "adopted" his childhood nanny, who had the thrillingly picaresque name of Jessie Lightfoot. She stayed on board until her death.

When times were hard, Nanny Lightfoot became Nanny Lightfingers and utilized her shoplifting skills to put food on the table. She would also vet the propositions Bacon received from ads offering his services as a "gentlemen's companion," which means exactly what you think. However, she was an avid advocate of capital punishment and "longed for the day when the gibbet would be re-erected at Marble Arch, with the Duchess of Windsor as the first public enemy to be hanged, drawn and quartered there."

Hanged, drawn and quartered? Sounds like something you might see in a Bacon painting.

Bacon, Sweeney Agonistes,1967

Here Comes the Judge

Artists are sometimes judged by their influence on other artists. Unfortunately, we would be hard put to come up with any painter influenced by Bacon -- except perhaps his friend, the older and very dreary Graham Sutherland. That artist's signature thorn-forms were clearly a reference to you-know-whose crown of thorns, but only under Bacon's influence did Sutherland attempt a crucifixion or two.

Brit critic David Sylvester's book of edited interviews (1975) reveals how dumb Bacon actually was, or at least pretended to be. He was certainly smarmy. And if he was trying to put himself across as an Abstract Expressionist who hated abstraction, or as a Surrealist, he failed. Sir Roland Penrose, when he was only Roland Penrose, rejected Bacon for his 1936 International Survey of Surrealism for being "insufficiently surreal."

You can catch two segments of the actual interviews on YouTube, notable now for the leading questions continually proffered by Mr. Sylvester. With a friend like that -- artists beware of critics with microphones -- you don't need an enemy.

On the other hand, now we can certainly say that Bacon influenced the face of cinema.

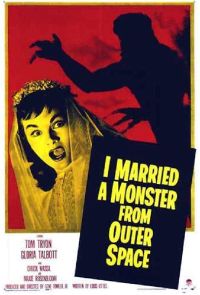

I Married a Queer From Outer Space

Desperate for something to watch, I recently turned to TCM on Demand and found, of all things, I Married a Monster From Outer Space, Gene Fowler Jr.'s crazed 1958 exercise in paranoia, with art direction by Henry Bumstead and Hal Pereira. I could not believe my eyes.

The movie's about a takeover of small-town husbands -- one by one -- by an alien all-male race that needs to find females to reproduce. It is really about gay men taking over the world. The "husbands" sulk and brood, bond with each other, and disappear in the middle of the night to go on long walks. But the "real" men -- breeders who have sired children and who own rifles and hunting dogs -- get them in the end.

Periodically flashes of lightning reveal the real faces of the alien husbands, who are without emotion and seem not to be able to impregnate their Westinghouse brides. This is how we know it is not just the zombie played by Tom Tryon who is a monster, but also several others, including the cops and a telegraph operator who stops a cable to the FBI. Do their real faces remind you of a certain artist's Picasso rip-offs?

Which face is the artwork?

[Scroll to end for answer.]

In spite of the socially and family-induced self-loathing, his acting out and acting up, and his profligate ways, Bacon has a life story and psychology (if you dare call it that) that are vastly more interesting and more entertaining than his ghoulish illustrations now on view at the Metropolitan. Although torture never goes out of fashion -- thanks to Cheney and Bush -- Bacon's dated specimens of beef, beefcake, and blood are at best paint-smeared, writhing footnotes to The Age of Anxiety. He would have loved waterboarding but have used it as titillation, not condemnation, or as just another metaphor.

Wouldn't we rather see a Leon Golub show at the Met?

Answer to photo quiz:

Left: Tom Tryon with alien face, I Married a Monster From Outer Space, art direction by Henry Bumstead and Hal Pereira.

Right: Francis Bacon: Three Studies for a Self-Portrait (detail).

Never miss an Artopia installment! For an Automatic Artopia Alert,

contact: perreault@aol.com

Received:

Art Strike 2010-13!

The refusal to labor is the chief weapon of workers fighting the system; artists can use the same weapon. To bring down the art system it is necessary to call for years without art, a period of three years...when artists will not produce work, sell work, permit work to go on exhibitions, and refuse collaboration with any part of the publicity machinery of the art world. This total withdrawal of labor is the most extreme collective challenge that artists can make to the state.

The years without art will see the collapse of many private galleries. Museums and cultural institutions handling contemporary art will be severely hit, suffer loss of funds, and will have to reduce their staff. National and local government institutions for the financing and administration of contemporary will be in serious trouble. Art magazines will fold. The international ramifications of the dealer/museum/publicity complex make for vulnerability; it is a system that is keyed to a continuous juggling of artists, finance, works and information--damage one part, and the effect is felt world-wide.

.......Gustav Metzger (b.1926) whose Years Without Art 1977-1980

said it all....and was almost completely ignored.

Strike Demands

Reinstatement of individual grants from the National Endowment for the Arts for artists, poets, and art critics.

Allow artists to deduct from their taxable incomes the full market value of their own artworks when these artworks are donated to museums, as is now the case for collectors and other investors.

Create a cabinet-level Secretary of the Arts.

The forced resignation of all art collectors and real-estate developers from the Boards of nonprofit art museums and art spaces, on the grounds of conflict of interest and profiteering.

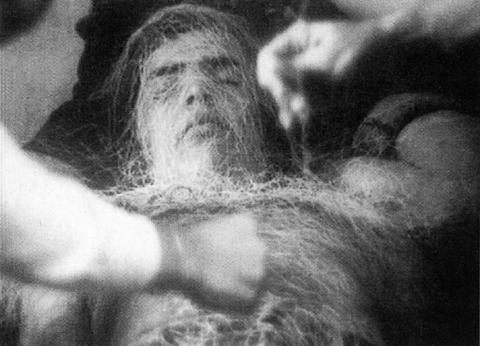

Gustav Metzger: Untitled (Auto-Destructive Art), 1961. Acid on nylon.

Metzger: Untitled. Recreation of above, 2006.

Who Is Gustav Metzger?

As fate would have it, Artopia's proprietor came across a remaindered copy of Gustav Metzger History History, Generali Foundation, Vienna (ed. Sabine Breitwieser) issued upon the occasion of Metzger's retrospective in 2005 in Vienna.

Born in Germany in 1926, young Gustav, accompanied by his brother, were transported to London in 1939 by the Refugee Children's Movement and thus, unlike the rest of his family, escaped the Holocaust.

In the late '50s he was both an anti-nuke activist and the founder of what was to be called Auto-Destructive Art. One manifestation of Auto-Destructive Art was his own creation of paintings by spraying acid on plastic sheets, causing them to disintegrate by the end of the performance. He was the instigator of the seminal Destruction in Art Symposium in London in 1966.

Both Yoko Ono and Ralph Ortiz were participants. Metzger was the initiator of projected art that seeded rock concert light shows.

More recently, now over eighty, he has systematically affixed pages from daily newspapers to gallery walls and also installed what he calls "Historic Photographs" - blowups of horrendous atrocity photos, displaying them behind false walls or behind or under fabric. In one case, viewers were allowed to crawl under a canvas to experience the now defamiliarized image placed flat on the floor.

Metzger: Installation of "Historic Photographs"

Metzger: 'History Photographs" (To Crawl Into - Anscluss, Vienna, March 1938), 2005, showing viewer looking at photo blow-up.

Another installation: Metzger: 'History Photographs" (To Crawl Into - Anscluss, Vienna, March 1938), 2005, showing viewer looking at photo blow-up.

In a severely reductive way (which is how we control true innovators), we only seem to know, if anything at all, that Metzger's actions and theories inspired both John Latham's chewing up and spitting out of Clement Greenberg's Art and Culture and the guitar-smashing antics of Pete Townsend of The Who. Why has there not been a museum exhibition of Metzger's work in New York City? Is his work too radical, too political? Could it be that because of the very nature of his art, there is too little to sell? Here is Metzger himself in a recent interview:

Art Strike IV?

It should also be noted that Punk/post-punk novelist artist Stewart Home -- famous in some circles for dressing up as his drug addict/ fashion model mom--also initiated a three-year art strike in Metzger's footsteps: 1990-1993. It was equally effective, and I am sure you noticed that the art world changed for the better after 1993.

Now we have yet another art strike, but initiated anonymously by person or persons unknown.

Maybe this strike will work.

If you count as an art strike the one-day, anti-Viet-Nam war moratorium of October 5, 1969 --- now apparently only remembered for Jasper Johns' American flag print commissioned by his art dealer Leo Castelli, then this is Art Strike Four.

Four strikes and you are out!

You Have Nothing To Lose But Your Theory

What would be gained by a three-year Art Strike? Such an activity -- rather, radical inactivity -- would accomplish several things not mentioned by Metzger in his historic challenge issued by the ICA, London, in 1974, now quoted by this new effort at an Art Strike.

As Metzger further stated so long ago, an art strike would cripple galleries and museums. Galleries, of course, could coast for one or two years on inventory, which is why the three-year moratorium is an absolute.

Now we need to add that museums would have to start barfing up selections from their inventory, otherwise known as permanent collections. After three years of this, the public would be totally bored, since there are only so many ways you can slice a cake

An art strike is risky. It strikes fear in the hearts of artists as well as the public. But without risk, a political action just like an aesthetic action has no force. So what is at risk?

One: It is not certain that the public will really miss contemporary art.

Two: It is not certain that artists will really miss making art.

Three: It is not certain that the collapse of the art system will result in the demise of the collector and the collector mentality; tulip bulbs or light bulbs or clown noses may become the next new collectible.

Four: It is not certain that "artists" will find other things to do to keep themselves out of trouble. Sexual shenanigans, alcohol abuse, and dangerous drug use could escalate.

Five: It is not certain that preparators, receptionists, art-handlers, framers, and all the cooks and waiters working in nearby restaurants and lunchrooms will ever again find gainful employment.

Six: It is equally uncertain that critics, curators, and the like will be able to find other ways of making a living. It is certain that parents will no longer think of art as a safe career for their clean-cut spawn and will therefore force them to go to law school or study engineering. This will depopulate degree-granting venues and their compulsion to have everyone in the world earn increasingly dubious MFAs to prove that they are artists. It would also have the added effect of forcing artists and critics employed as teachers to find other, more socially productive, more intellectually challenging and culturally enriching employment.

* * *

Here, in the spirit of the anonymous Art Strike missive, are the questions that urgently need answers:

Will anyone make art if there is absolutely no chance of making money out of such diddling?

How much fresh air can the art world stand?

Once gainful employment is again the norm, will anyone have time for squeezing out art?

Will envy and competition disappear? Will bitterness and commercialization dissolve?

Previously:

"Pictures Generation" at the Met Please scroll down.

Oldenburg at the Whitney Please scroll down.

Ernesto Neto at the Armory Please scroll down.

Never miss an Artopia installment! For an Automatic Artopia Alert,

contact: perreault@aol.com

Not Every Picture Tells a Story

"The Pictures Generation (1974-1984)," now at New York's Metropolitan Museum through Aug. 2, proves that pictures will not cure you of photography, any more than the hair of the dog will cure you of rabies.

The exhibition offer as many insights about photography as it does about spinach.

The so-called "Pictures Generation" was never an art movement; it was hardly a trend. That two of the artists so packaged way back in the dim past have emerged as art-world superstars -- Cindy Sherman and Richard Prince -- may be more of an explanation for this investigation than anything else.

Why these two and not any of the others? In the first room of the exhibition, which features early work, Sherman's self-portraits jump from the wall. Or is this hindsight? Prince is virtually indistinguishable from the common lot.

Yes, there are photographs in "The Pictures Generation," and certainly Louise Lawler and Laurie Simmons are represented by their dull photographic fare. On the other hand, Sherman is as much a performance artist/ makeup artist as a photographer. She makes faces of her own face. She paints herself out of her pictures; she is myriad. She is the actor-artist.

Because of the context, both David Salle and Robert Longo -- artists I usually have no interest in -- turn out to look better than they have in a long time. Two paintings by Salle stand out because in a world of processed images raw paint always wins. Longo's iconic "Men in the Cities" Triptych, removed from the accumulation upstairs, holds its own in the Met's huge lobby -- which is a lot to be said for drawings, even big ones.

Otherwise, too much early work. Too much weak work. And we are left to sort through the mess. Art critic/art historian Douglas Crimp's "Pictures" exhibition at Artists Space in 1977 was, in theory, seminal --- launching the "Pictures Generation." That very dull little show, however, occasioned Crimp's influential Artforum essay. The concept at the Met seems to be that the assembled motley crew -- most of whom were not in Crimp's exhibition --- represents a kind of postconceptual image-making, retaining "concepts" from Conceptual art but illustrating them with images from the mass media.

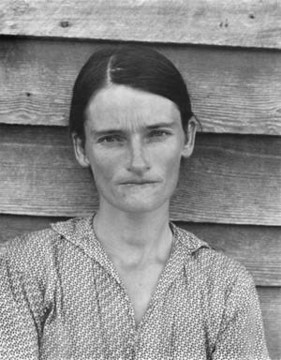

None of this was new in 1977, with one possible exception: out-and-out appropriation -- as it came to be called -- by Sherrie Levine. She re-photographed Walker Evans' classic photos from reproductions in a book.

Otherwise, we could just as easily say we are looking at Pop Art Two.

Too bad the recent Walker Evans show at the Met is now closed.

The Pictures Generation isn't a generation like the Lost Generation or even like Generation X; it is packaging, which is ironic, considering the claims made. Critique of capitalism? Exposure of the image nation? Give me a break.

Does the Artopia 10% Rule for mediocre surveys still apply? Yes. Out of 30 artists, Barbara Kruger, Levine, and Sherman are the only clear winners

.

Untitled © Sherrie Levine

Previously:

Oldenburg at the Whitney Please scroll down.

Ernesto Neto at the Armory Please scroll down.

Forthcoming:

Art Strike Announced, Available on-line:Tuesday, May 26.

Never miss an Artopia installment! For an Automatic Artopia Alert,

contact: perreault@aol.com

Ice Bag Restored

Centered around the artist's newly restored Ice Bag - Scale C (1971) -- it inflates! it slumps! it rotates! -- Claes Oldenburg: Early Sculpture, Drawings, and Happenings Films (through Sept. 8) is drawn primarily from the Whitney permanent collection. Occasioned by the dire economics of the moment, this is one of those exhibitions that proves necessity can be inspiring. Who knew that the Whitney owned so many tasty Oldenburgs?

We love the absurdity of the Giant BLT (1963), French Fries and Ketchup (1963), and of course the Ice Bag is a hoot. The squeaky-clean musical-instrument collaborations between Oldenburg and his late wife Coosje van Bruggen ("The Music Room") are offset by a small collection of messy items from Oldenburg's project/environment The Store (1961), of which the painted-plaster Half Cheesecake, Potato Chips, and Pile of Toast are standouts.

Oldenburg's drawings -- post 1965 -- are too commercial and too academic. Maybe that's the joke. The same can be said for the most of the monuments. A giant fire plug is fun only once. And a drainpipe not even once. But wouldn't an exhibition focused just on Oldenburg's food sculptures be wonderful to see?

Also fully restored are a collection of films that give us glimpses of Oldenburg's legendary Happenings. Allan Kaprow may have been the first Happenings guy, but Oldenburg and many others - such as Jim Dine, Red Grooms and Al Hansen -- also joined the fun.

Although it is wonderful that these historic films have been saved and brought back to life, they are also reminders of how messy and unstructured Happenings tended to be, with one foot in Action Painting and the other in farce. Because the footage has been shot and then chopped up and edited by various filmmaker/artists -- Stan VanDerBeek being the most famous -- to make artworks of their own, there is no sense of what real time came into play. We get a mélange of images, actions, and guest appearances by Carolee Schneemann, Lucas Samaras, and Henry Geldzahler, but an understanding of the Happenings form (or lack of form) is not helped by the seven-screen presentation of seven different films simultaneously.

We are reminded why Performances (as perfected in the late 1960s by Vito Acconci, Scott Burton, Marjorie Strider, Hannah Weiner, and the founder of Artopia) were not Happenings, but much more conceptual presentations, reacting against Happenings.

Nevertheless, noting down the address from Oldenburg's poster that advertised The Store, I forthwith made a pilgrimage to 107 East 2nd Street, now looking curiously like a vintage tenement, with bars on the ground floor windows....

Art Shrine Consecration

There are too many as yet undesignated Art Shrines in New York City. Artopia hereby recognizes 107 East 2nd Street, the site of Claes Oldenburg's 1961 The Store, as the first official Art Shrine. Monies are now being sought for a bronze plaque that will eventually be put into place announcing this fact.

Certainly the site of the Judson Gallery in the basement of Judson Church in the Village Proper, as opposed to the East Village (the Village Improper), will also be considered, since it was the venue for many now-famous Happenings and Ralph Ortiz's Destruction Art chicken decapitation. We are also looking into 111 St. Mark's Place, the site of the One-Eleven Gallery, where in 1961 -- a seminal year -- Artopia founder John Perreault had his first art exhibition. It was also the site of a Happening by Al Hansen. Nominations for additional Art Shrines are now being accepted.

Previously:

Ernesto Neto at the Armory Please scroll down.

Forthcoming:

'The Pictures Generation' at the Met, Friday, May 22.

Art Strike Announced, Tuesday, May 26.

Never miss an Artopia installment! For an Automatic Artopia Alert,

contact: perreault@aol.com

In The Womb of the Tropical Spider

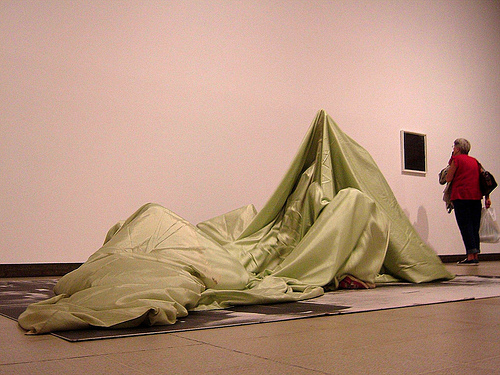

Lycra deployed like tenting, like venting, like pastel parachutes and saliva, forming a gigantic "spider" with udderlike, fabric stalactites weighed down with turmeric, glove, ginger, black pepper, and cumin introduces the hallucinatory feminine into the splendiferous, all-male, historic Park Avenue Armory.

One needs people cautiously making their way through the fabric passageways; one needs children innocently romping to see the danger of this participatory venture.

Brazilian Ernesto Neto's anthropodino (through June 14), a jaw-dropping marriage of science-fiction and the nursery, is magnificently creepy.

Those of us who know a little about Brazilian art immediately see the references to the nests and participatory environments of Hélio Oticica (1937-1980) and the healing art of Lygia Clark (1920-1988).

Hélio Oticica: Paragoles (1965-79)

Oticica and Clark were co-founders of Neo-Concretism which progressed from Neo-Plasticism, to art variables, to multi-sensory and multi-sensual participatory art. Clark, in particular, was an artist who truly seems to have come from another planet -- a genius who has not yet received her due. Some of her healing rituals involved sand-filled fabric tubes placed on various parts of the body.

Lygia Clark: Baba Antropofagica [Cannibalistic Slobber], 1973.

In the meantime, Neto's vast playpen is a good reminder that there are art worlds within art worlds and fields of "otherness" not yet conquered because we stay too focused on what peaks and speaks (or used to peak) in auction houses.

Forthcoming on Artopia:

Oldenburg at the Whitney, Wednesday, May 20.

The Pictures Generation at the Met, Friday, May 22.

Art Strike Announced, Tuesday, May 26.

Never miss an Artopia installment! For an Automatic Artopia Alert,

contact: perreault@aol.com

AJ Ads

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Exploring Orchestras w/ Henry Fogel

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary

Tyler Green's modern & contemporary art blog