Artopia: February 2009 Archives

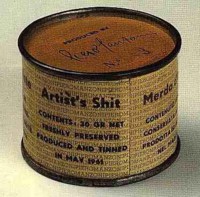

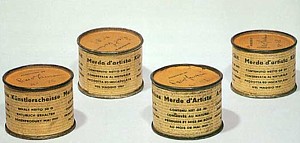

Piero Manzoni: Merda d'artista, 1961

When the Shit Hits the Fan

1. Let's get it over with, right here at the beginning: excrement, feces, crap, poo-poo, doo-doo, ca-ca, poop, turds, shit. Notice how so many of the words are baby-talk. Like Dada.

2. "A wonderful fertilizer -- money."

-- Percival "Money Bags" Montgomery Hower (played by Clyde Fillmore) in Josef von Sternberg's 1941 Shanghai Gesture

3. St. Manzoni or baloney?

His rabid involvement in the polemics of art and the art world finally pushed him to the brink of psychological collapse (see R.D. Laing, The Divided Self), which in turn moved him in the opposite direction of his desire to purify, whiten, and conceptualize all things. His inner conflict ended in tragedy.

In 1961, in an act of defiant mockery of the art world, artists, and art criticism, which in unison treated him as though he were retarded, Piero Manzoni invented The Artist's Shit. He performed the operation himself: produced it, put it in a box [sic], sealed it, labeled it, numbered it, and signed it. This filthy gesture brought all his relationships -- not only with the art world but also with his own former aspirations toward visual and conceptual purity -- into crisis. He became increasingly restless; he started to travel and to drink heavily.

By the age of thirty he had drunk himself to death.

-- Enrico Baj, 1990

Freshly Preserved

Shit is what convinced me that I wanted to be an artist when I grew up -- shit, not my own, and a little bit of sibling rivalry. "Come and see what he is doing now," said my aunt to my mother, meaning my baby brother. When Mom entered the room, she exclaimed that Baby Ronnie was an artist. He had been playing with his own ca-ca, delightedly smearing it all over himself, the crib, and any part of the wall he could reach.

Was she thinking of de Kooning or Pollock? Neither. It was several years before my mother could have seen photographs of Abstract Expressionist paintings in Life magazine. I was six. I was ignored.

However, I was the one who left home to become a poet and an artist. Adorable Baby Ronnie stayed home and took over the family business.

Some cans of Merda d'artista (1961) are on view in the Piero Manzoni museum-quality retrospective at the Gagosian Gallery (555 W. 24th St., through March 21).

I give MoMA high marks for its Hsieh exhibition, but shouldn't this Manzoni retrospective have been on 53rd Street? Replacing ... ? Well, never mind. And where is the Guggenheim when we need some smarts? Forget MoMA and the Guggenheim, this Manzoni exhibition should have been in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which is currently wasting its resources, its space, and our time on Bonnard -- late Bonnard, no less.

Sam Goodman, Untitled, 1964. Rebuilt by Ditmas Kirves, 2001.

Boris Lurie, Red Shit, 1964. Extruded plaster and paint.

The Doo-Doo Detective

Manzoni's shit, "worth its weight in gold" (for that is what he sold it for), started me looking for turds in art beyond Ubu Roi. Didn't a 10th Street artist once exhibit shit sculptures?

I searched my memory and at first I came up with Bob Kaufman, who turned out to be a Beat poet who didn't have anything to do with shit sculptures. And then (a miracle!) the name Sam Goodman came to mind. It was shit-search gold.

Of course, the "NO-sculptures/SHIT show" was uptown at the Gertrude Stein Gallery, not at the March Gallery on East 10th Street and not in 1960 as I had remembered, but in 1964. At that time Gertrude Stein (not Alice's girlfriend) had befriended the March Gallery NO!art Group, or at least the founding troika, Goodman (1919-67), Stanley Fischer (1926-80), and Boris Lurie (1924-2008). And, such is memory, whereas I remember real turds on pedestals, the shit was really floor-sculptures made of extruded plaster. There were 21 shit floor-sculptures, one of which weighed 600 pounds. And they were not all by Goodman. He and Lurie had worked on the then infamous feces fete together.

The show created a media frenzy, led to venues abroad, but disconcerted the artists:

Paradoxically though -- to our amazement and frightening surprise -- the pop collectors-speculators began to show up professing to like the show, claiming to want to buy and promote it. I believe their feeling was quite sincere in the context of their thought, though they totally misunderstood content and intent. This was a frightening experience to us, we suspected we possibly had gone wrong, that our intentions had misfired, ricocheted in a way not anticipated, feared our newly found appreciators -- and enemies in some twisted yet true way had understood the true content of our work better than we thought we did...

-- Lurie, NO!art, Edition Hundertmark, Berlin/Koln, 1988. p.63

This led me to the NO!art site, where I found a filmed interview with Lurie, who has quite a story to tell: Nazis internment, contempt for the art world, and, yes, a retrospective in the buildings of the Buchenwald memorial. You should also hear what Gertrude Stein, the art dealer, says about the art world and the art museums way back in '64, prompting the question: Is it any better now?

Pausing for a moment on the NO!art site, I made note of the following "involved artists": Paul Georges, Leon Golub, Allan Kaprow, Kusama, Lil Picard, and Michelle Stuart. (You can read Stuart's NO!art statement by clicking here.)

Here's a tease quote from her text:

Sam Goodman has salvaged from the abundant trash barrels, garbage heaps, and overflowing gutters of New York carcasses of TV sets, play guns, mangled dolls, crutches, airplanes, bombs, bibles, toy cash registers, crucifixes, even a globe of the world. As he assembles these objects the toy guns turn into threatening weapons, the dolls into frightening reminiscences of the charred bodies of Hiroshima or Auschwitz, the Bible a purity degraded, and the cash register a demoralising symbol of power.

There is no escape from the claws and the jaws of art history!

But art is strange: Now I wonder what in real life I would think of Goodman's crushed dolls and Lurie's collages of nubile nudes and Holocaust pictures. Would the increasingly tiresome New Museum dare to put up a NO!art show while the material can still be found? Are the collage/assemblage works of the March Gallery Unholy Three (Fischer, Goodman, and Lurie) just Rauschenberg with horns? Sexist shock-schlock and agitprop? I really don't think so.

Nevertheless, here's the Art Detective's big question: did Goodman and/or Lurie in 1964 know of Manzoni's 1961 canned shit? Baj knew Manzoni (see quote above); the March Gallery guys knew Baj, for he is included on the NO!art website as an "involved artist."

But fake shit on the floor is far different from an artist's real shit in a can. Even if the Goodman "shit" had been genuine excrement or, better yet, artist-produced do-do, Manzoni's packaging makes his shit say much more. Was he against the packaging of art? The artist? Was he against the privileging of gold over shit? Was he against canned goods?

All of the above, and more. Did he understand the deep infantilism of art production (and perhaps, yuk, art consumption)? If not, he certainly was lucky enough to hit a vein of gold.

Andres Serrano, Self-Portrait, 2008. Photograph.

Toilet Training

And now how are we to deal with Andres Serrano's and Paul McCarthy's more recent entries in the shit sweepstakes?

Both last year offered shit of note. Serrano's Self-Portrait was the standout in his September show at the Yvon Lambert Gallery showing of super-large photos of mostly animal poop. Serrano seems to think he invented Leonardo da Vinci's advice to seek images in flaking walls, substituting shit. Will poor pooches on leashes now have to beware of lurking artists waiting to pounce on their poo like the poop-eating Divine at the end of Pink Flamingos?

Paul McCarthy: Complex Shit, 2008. Inflatable.

McCarthy's Complex Shit is notable because last August this giant inflatable turd broke loose from its moorings at the sponsoring institution, the Zentrum Paul Klee in Bern, Switzerland, damaging some power lines and/or crashing into a greenhouse.

But, let's face it, Manzoni remains the master of merde.

Piero Manzoni: Base of the World, 1961

The Manzoni Legend

Beginning with the all-white achromes (c. 1957) until his death in 1963, Manzoni had only six years of topnotch art production. He died of "a fatal infarction," otherwise known as a heart attack or, more dramatically, depending upon whom you read, "cirrhosis and exposure to extreme cold." His last exit occurred either in his studio or on the steps of his studio. If exposure had anything to do with his untimely demise, I'd vote for the latter.

The motivated reader can find fairly detailed lists of the kinds of artworks he produced by going to the Piero Manzoni Archive (click here) or the Manzoni entry on Art Minimal & Conceptual (click here). For something more discursive, Jan Van der Marck's 1973 Art in America essay remains a readable summary (click here).

Briefly, the Manzoni output was:

1. All-white paintings initially made of clay-soaked canvas.

2. Balloons containing the artist's breath.

3. Living sculptures signed by the artist.

4. Pedestals for "living sculptures" -- and one for the earth itself.

5. Very long lines inscribed on scrolls and sealed in tubes.

6. Most notorious and victorious, his very own canned shit.

Manzoni with one of his Living Sculptures.

Yves Klein (1928-1962)

Comparisons Are Odorous

Do we dare compare Manzoni to Yves Klein? The old rule that you should not compare apples to oranges is not my rule. What better way to see what is unique to apples and/or to oranges? Why not, says Professor Perreault, compare de Kooning to Pollock? And why not Manzoni to Klein?

Manzoni and Klein (for the Klein archive click here) both had a gift for showmanship. And although on at least one occasion he was in a group show with Klein, it would have been difficult I suppose for the Italian creator of various scrolls of single-line drawings and the champion of non-color to reconcile himself to Klein's motto: "For color! Against the line and drawing!"

Oddly enough, in photographs at least, the artists looked suspiciously alike. Or did they merely have the same barber?

Both had a commitment to the monochrome: Manzoni to the "non-color" white, Klein to his patented International Klein Blue. Both paid homage to -- or exploited? -- the female nude. Klein used naked models as painting tools, to press IKB body-prints on canvas to the tune of his Monotone Symphony.

Manzoni signed female nudes, and, though I have never seen a photograph of such, men too. Did the men have their clothes on? Some clever artist, male or female (each gender unveiling particular meanings), should recreate these works using male nudes. Or just imagine such works. What in each case would you, a male, think of such carryings-on? What would you, a female, construe?

Manzoni's World Pedestal -- which claims the whole earth as a sculpture -- almost has the grandeur of Klein's Leap Into the Void, showing him leaping out of a window. But paradoxically, Manzoni's clever pedestal is far less cosmic. After all, Klein had been a Rosicrucian, had a black belt in Judo, and was officially ordained a Knight of the mysterious Order of the Archers of Saint Sebastian.

Klein, Leap Into the Void, 1960. Photograph.

In contrast, by many accounts Manzoni was somewhat of a schlemiel -- inarticulate and short. Yet at present he appears ferocious and gigantic. And perhaps a bit of the holy fool, whose relics are now ... expensive. And it is his shit, not his all-white paintings (which seem fussy) that makes him Saint Manzoni.

Manzoni and Klein -- no matter what their roots in the avant-garde of their time -- both danced to a different tune, one now rarely heard in the art world. It is as if we are looking at artists from another planet, another universe.

Klein, by the way, died after not one but a series of heart attacks. The first of three occurred while he was watching the exploitive Mondo Cane at the Cannes Film Festival in May 1962. Through the miracle of the Internet, embedded below is what Klein saw at Cannes. The drama of the Monotone Symphony unfortunately yields to cocktail music; Klein is identified on the soundtrack as a Czech artist. Is that what gave him the heart attack? But please note how his blue paint becomes a clever metaphor for excrement.

Deeper Into Shit

Delving deeper into the Baj text, I want to deplore the polarities of purity and danger, white and brown, sacrament and excrement, art and shit. These "polarities" probably escaped Manzoni. Artopian artists tend to work outside of dichotomies. As Dadaist Tristan Tzara proclaimed, art is anything the artist spits out. This may not really solve the definition/identity problem, but at least it subverts formalist definitions and allows some wiggle room.

It is not much of a stretch to change spit to shit. Art is shit. Art is produced by the artist's body. Or is art really the waste product of the artist's nervous system? Or the critic's brain?

Manzoni's canned shit proclaims that gold and shit are equivalent in terms of ultimate value. Gold is shit. Monetary value is shit. Freudians know of these shit/money equations. They also know all about the infant's more than fickle fecal gift.

Purity too is a kind of shit -- bullshit. Humans cannot produce purity, much less perceive it. Even so, Manzoni himself never achieved the gratuitous "purity" of, say, Rauschenberg's all-white paintings of 1951, one of which is on display at Gagosian as part of several touchstone lineups intended to put Manzoni in context.

I think Manzoni's all-white achromes, whether composed of calcium sulfate-soaked canvas or gone all feathery, linger over texture far too long. Manzoni never achieves the nothingness of Klein's all-blue monochromes or his exhibition of an empty art gallery. When it comes to Manzoni, only his shit was pure.

So was there indeed some deep conflict expressed by what some might see as an opposition between Manzoni's white paintings (e.g., purity) and his canned shit (e.g., danger) that, suggests artist Baj, led to Manzoni's unusual premature demise? That opposition is too simple. If there had been any disequilibrium, it was caused by Manzoni treating purity and shit as identical, not as opposites. Or in his own immortal words:

It is not a question of shaping things or of articulating messages. (And one can't resort to extraneous interventions, parascientific mechanics, psychoanalytic intimacies, graphic compositions, ethnographical fantasies because every discipline carries within it the elements of its own solution.) For are not fantasizing, abstraction, and self-expression empty fictions? There is nothing to be said: There is only to be, to live.

OWN THE FUTURE: FOR AN AUTOMATIC ARTOPIA ALERT CONTACT perreault@aol.com

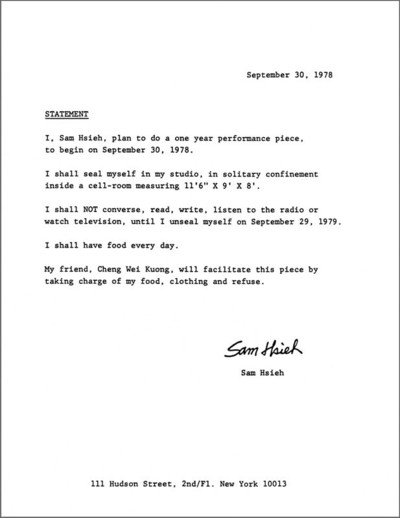

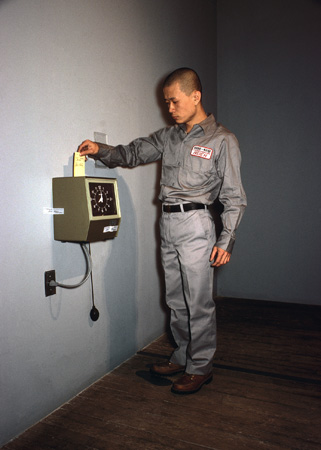

Tehching Hsieh has created only six artworks or, more precisely, performed them. This is not counting his earlier jump from a window in Taiwan or, before that, the paintings he made. The six artworks are the ones he lists on his website and that have been validated as art and valued as such.

* * *

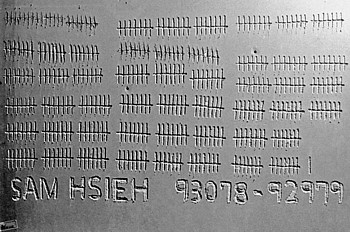

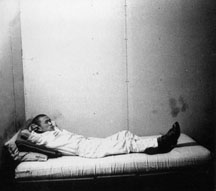

1. One Year Performance 1978-1979 -- Hsieh lived in a locked cage without reading, writing, or talking to anyone, which is now fully documented at the Museum of Modern Art through May 18. What we focus on at MoMA is a wooden cage that includes, according to the wall label: "bed, mattress, pillow, blanket, sink, can, mirror, sheetrock walls, toilet paper roll, paper towel roll, toothbrush, bar of soup, nail clippers, glass cup, glass bottle, marked footprint, uniform, shoes, light bulb, tea bags, sponge." Outside the cage, a lineup of photographs charts hair growth from shaven head to mangy mop. There's a typed statement, sample handbills, and more photos, in themselves undistinguished, just doing their business as proof. You should also know the artist sometimes called himself Sam Hsieh.

At MoMA, it is illuminating to see the "sacred" residue of Hsieh's first One Year Performance. Although we would have preferred a full survey of all six artworks, Artopia salutes the occasion. Since the current manifestation is not a retrospective, we hereby offer brief summaries of Hsieh's complete oeuvre.

* * *

2. One Year Performance 1980-1981 -- Hsieh punched a time clock every hour on the hour. Can you know about this piece without thinking of drudgery?Bank executives do not have to punch clocks, do they? Are you punctual? What does being punctual mean? Have you ever worked in a factory?

* * *

3. One Year Performance 1981-1982 -- Hsieh lived outdoors in New York City.

Can you know about this piece without thinking of the condition of homelessness? The horror of homelessness? Now you will always wonder if the homeless man or woman you see in the street -- or try to avoid seeing -- is an artist, or perhaps a saint.

* * *

4. Art/Life One Year Performance 1983-1984 -- Hsieh and artist Linda Montano were tied together by a length of rope.

We will stay together for one year and never be alone. We will be in the same room at the same time, when we are inside. We will be tied together at the waist with an 8 foot rope. We will never touch each other during the year.

For anyone who might think that Hsieh is certifiable, here's proof that he is perfectly normal: In a 2003 Brooklyn Rail interview he complained that Montano had taken too much credit for the rope piece and, in any case, it was his idea: "She took that piece and made it hers. Most people think that was her piece. The picture she always uses I don't like it either. She is in the foreground and I am in the background."

This should dispel the notion that there was something Buddhist or Zen about Hsieh's approach to artmaking.

Montano, a considerable artist in her own right, claims in a 2002 interview she saw one of his posters in the street and heard a voice in her head say: "Do a one-year piece with him." She also said his "concept ART/LIFE: ONE YEAR PERFORMANCE was inspiring, and when I decided to join him in his rope piece for a year and I got to work with this 'genius of art', I learned so much about time from him."

There's a report she is now a novice at Maryknoll Sisters in upstate New York.

* * *

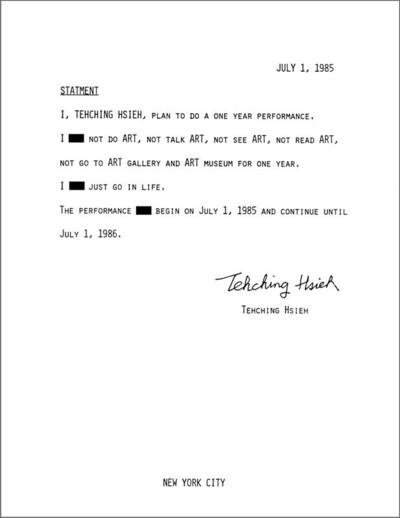

5. One Year Performance 1985-1986 -- Hsieh did not view, make, discuss, read about or in any other way participate in art.

Was this in response to being tied to Montano?

* * *

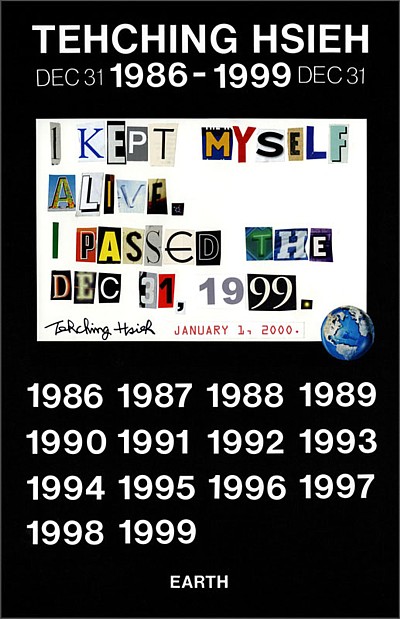

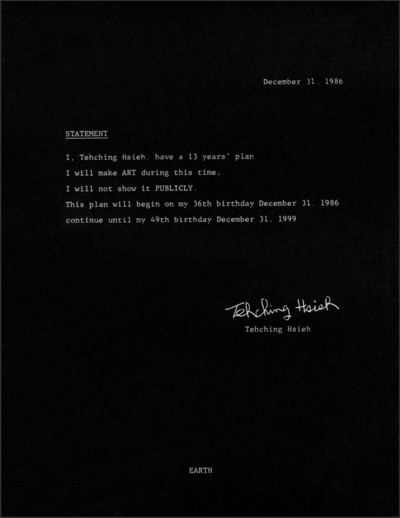

6. Thirteen Year General Plan 1986-1999 -- "I kept myself alive." .

I have included Hsieh's final piece, though some might question that it has been fully accepted as art. I think it has been validated through the strength of the previous performances. Furthermore, it is -- how shall I say it? -- subtle. It is not clear, for instance, what artworks he made, if any, beyond just surviving. What is clear is that after this point, Hsieh no longer called himself an artist.

* * *

What Is Originality?

Hsieh claims, in terms of his Taiwan jump, that at that time he did not know of Yves Klein's 1969 Leap Into the Void, nor had he even heard of that spiritual prankster. But when Hsieh decided to live in a cage for one year in New York City, had he known of Joseph Beuys' I Like American; America Likes Me? Beuys flew to N.Y.C. and, swathed in his signature felt, had himself delivered by ambulance to the Rene Block gallery in Soho and for three days preceded to live in a caged-off space with a coyote.

It now looks like Klein faked the purported photo of his jump through the magic of the darkroom, which, of course, does not invalidate the metaphysical import. Beuys performed his cage piece in 1974, the year Hsieh jumped ship outside of Philadelphia and took a $150 cab ride to New York City. Beuys' cage piece did not last an entire year, like Hsieh's 1978-79 work. Hsieh's feat did not include a coyote.

I think we can safely dismiss Hsieh's 1973 "jump" as juvenilia, notwithstanding a poster he made to document this leap. The jump resulted in two broken ankles.

Hsieh's cage piece is, in its relationship to the German master's cage piece, quite another story. Whether or not Hsieh knew of Beuys' artwork is not as important as is his timing. Four years is just enough distance. To spend one year living in a cage as opposed to a few weeks is more than a difference of degree. Furthermore, living alone in a cage with all the overtones and undertones of solitary confinement that this entails sets up meanings far different from the shamanism and the nature/human nature complexities of Beuys' visionary artwork, which I myself witnessed. Beuys claimed to be making a statement against the war in Viet Nam. Four years later, Hsieh's complexities were all his own.

If I were to live in a cage for one year, beginning tomorrow and ending a year from now, would that have different meanings? At this point in time, it would be classified as appropriation and probably be dismissed. But leaving appropriation aside, wouldn't it be an entirely different piece because I am an entirely different person? We know for instance that when Hsieh performed his cage piece he was then an illegal alien. I am not. Hsieh's self-imprisonment has to be seen at least partially as a metaphor then for his status as an alien -- "imprisoned" by isolation and fear and/or his possible future incarceration. Plus all the anguish that existentialism once allowed -- in fact, necessitated.

Hsieh has stated that all six of his works are about struggle.

If John Perreault were to live in a cage for one year, one could not avoid the suggestion that it was a symbolic manifestation of being imprisoned by art, or perhaps by an established identity as an art critic, poet, or artist. Plus all the anguish that existentialism allows

If Hsieh himself were to relive his cage piece now, it would also be a different piece: you cannot step into the same prison twice. Only the duration would be the same, if that.

Hsieh's cage piece, compared to Beuys' coyote classic, is more minimalist, more self-involved, and in some ways more difficult. Like the one year performance of living outdoors, the Hsieh's cage piece communicates the radically forlorn, which I tend to think of as a philosophical category.

Hsieh's six artworks make most art in comparison look weak and pandering, unfocused, bereft of meaning. Where in art has all the rigor gone?

Hsieh's six works form a natural progression from the fullness of the cage piece to the zero-degree affect of the 13 Year General Plan. Hsieh's 13 years of nothingness were not like Marcel Duchamp's, who allowed everyone to think he had given up art but, in fact, was making secret artworks.

On the other hand, Hsieh in 1986 had already made a work that consisted of not making or looking at art, so what could follow? Neither making nor not making, if we dare to imagine such. This is what I hypothesized, but it was not exactly his intention, according to his first statement:

I like my artwork better. I like my misunderstanding. In fact, in 2003 in the Brooklyn Rail, Hsieh was able to make a clarification:

O.K., everything I do is a progression, an evolution like the earlier pieces, it doesn't make sense. Do you understand? The next logical step was to just surivive into the next century, the new millennium.

Not everyone can or should continue making art for a lifetime. Inspirations come and go; being an artist is a state of being. Art making can become a bad habit or merely a business. Is it possible just to quit while you are ahead? In another realm, is Herman Melville any less a novelist because he stopped writing prose about 1867 and became a customs inspector?

FOR AN AUTOMATIC ARTOPIA ALERT CONTACT perreault@aol.com

AJ Ads

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Exploring Orchestras w/ Henry Fogel

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary

Tyler Green's modern & contemporary art blog