Artopia: February 2007 Archives

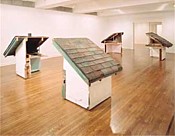

Gordon Matta-Clark: Splitting: Four Corners, 1974 (Courtesy, SFMoMA)

1. Gone Too Soon

Several themes are suggested by the Gordon Matta-Clark exhibition now at the Whitney (945 Madison Ave., to June 3, 2007), not the least of which is the early-death conundrum. Why do the best and brightest seem to die before they are 40? Here's a list: Eva Hesse (1936-70), Robert Smithson (1938-73), Matta-Clark (1943-78), Ana Mendieta (1949-85).

Many without talent die young too, and perfectly decent artists go on and on. Some even continue to produce credible work, although few indeed have Matissean late-life flowerings. Perhaps de Kooning. Pollock, of course, went out in his prime. And is that where the valorization of early expiration comes from? Or do we have to go back to John Keats, who was dead at 26?

Some have opined that an early death limits inventory and therefore raises price-per-piece on the well-worn principle that short supply plus high demand equals high return. Yet, contrary to this, I have heard that collectors like a lot of stuff floating around to show that the artist was/is a player. The potential for profit is even higher when there is a surfeit of merchandise at hand.

Perhaps more artists should impose on themselves a symbolic early death, in the manner of Marcel Duchamp who went "underground" around the ripe old age of 36. And before him there was poet Arthur Rimbaud, who quit writing at 18 and became a gunrunner in North Africa.

If artists stopped while they were ahead, we would be saved the spectacle of talents repeating themselves for the market and diluting whatever innovations made them visible in the first place. And we'd be spared the sadness of artists who once were good, who once were great.

Early death, even by cancer (which is what took Matta-Clark at the age of 35) makes a more dramatic story than expiring in a nursing home at the age of 89. Of course, if you live to 105, like Beatrice Wood -- that's another kind of story.

Dennis Oppenheim, Annual Rings, 1968

2. The Second-Generation Syndrome

Matta-Clark was a second-generation earth artist, but one who carved buildings instead of landscapes. In fact, as a architecture student at Cornell, he assisted Hans Haacke, Dennis Oppenheim, and possibly Smithson in the famous 1969 Earth Art exhibition. Oppenheim made circular "cuts" in the ice of a frozen lake; within a few years Matta-Clark was making cuts in buildings.

The art world does not like second generations. "Second generation" sounds second rate. My theory is that second-generation Abstract Expressionism was so awful it ruined it for all future second generations. I will not give you names. You know who they are, or if you're lucky you don't.

Second generations are anathema. What happens now is that we need to skip a generation and add a prefix. Neo-Pop is O.K.. just as Neo-Dada before it seemed perfectly sensible, although in the latter more than one generation was skipped.

First is not always best. Except in the art world, which is not a reasonable place. First is best because first can be proved, whereas best is a matter of taste. Too often one hears otherwise perfectly swell artists raging about having been the unacknowledged first to....you name it. Drip paint. Paint comic strips. Use silk-screens for paintings. Eschew the pedestal. Use a bulldozer or a chainsaw to make sculpture.

Matta-Clark was held back at the time he was making his breakthrough building cuts - now iconic and perennially influential - because (1) some thought he was copying the earth artists; (2) his sponsors for the remarkable Splitting of 1974, in which he cut an awful New Jersey house in half, were the collectors Horace and Holly Solomon. I liked Holly a lot even when she opened a gallery, but she had studied at the Actors Studio, was fashion-conscious, and was never taken as seriously as Virginia Dwan. Dwan came from Hollywood royalty and was able to scoop up most of the Big Boys of Minimalism and Earth Art, leaving them to John Weber when she closed. And....

Matta (Roberto Sebastián Antonio Matta Echaurren). (Chilean, 1911-2002). Listen to Living. 1941. Oil on canvas, 29 1/2 x 37 7/8" (74.9 x 94.9 cm).

MoMA, Inter-American Fund. © 2007 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

3. The Silver Spoon

Matta-Clark's father was Matta (Roberto Matta Echaurren) the celebrated surrealist painter from Chile, who was one of the links between Surrealism and Action Painting. If the illusionistic surrealism of Salvador Dalí was first generation, then Matta's wild, nearly abstract, sci-fi surrealism was second generation.

Shortly after the birth of the Matta twins (Gordon and Sebastian), Papa Matta divorced his American wife, Anne Clark. Later Matta-Clark did later spend time with his father in Paris, who urged him to be an architect. Matta pére had studied with Le Corbusier, but bailed out of that dismal art. Nevertheless, he recommended to his son that he seek out his old New York friends Frederick Kiesler and Philip Johnson.

Matta-Clark did graduate from the architecture program at Cornell, but, like his father, he preferred art, specifically sculpture, as opposed to painting. The closest he ever got to theory was to call his project "anarchitecture," which takes on additional meaning when you read Spyros Papapetros' excellent and playful catalog essay ("Oedipal and Edible: Roberto Matta Echaurren and Gordon Matta-Clark"). Matta-Clark's father urged him to buy a house or a loft so that his mother and twin brother would feel secure.

Sebastian fell to his death out of a window of his brother's loft.

a. Matta-Clark: Circus, 1978

b. Picabia: Tres Rare Taleau..., 1915.

c. Deborah Remington, Untitled, n.d. (c.1966?)

4. Documents Become Products

How are we to look at Matta-Clark's color Cibachromes? They document various cuts. They are, we learn in the catalogue, blow-ups of tiny collages the artist made from 35mm positives. They are what we know of the sponsored building alterations, but they are more. If you squint, they look like Deborah Remington paintings, which in turn remind us of certain obscure mechanistic paintings by Picabia.

I am not alone in pointing out that the Cibachromes were Matta-Clark's answer to the documentation question raised by Earth Art and other nongallery manifestations in the late '60s. Smithson invented non-sites: bins and piles of rocks accompanied by banal snapshots and maps. Jan Dibbets began making multiple photographs the point of his art. The parts were assembled into geometric forms.

Unless we recognize Matta-Clark's Cibachromes as the artist's reinterpretations of no-longer-existing architectural interventions, they are merely handsome photographs. If one approached the work from a photography p.o.v., you could say that the chain-saw holes cut into floors and walls are only set-ups for the Cibachromes, which provide multiple points of view.

I'd give them a place of high honor in my imaginary exhibition that documents Late Cubism: de Kooning's "Women," all of Louise Nevelson, and 99% of Robert Rauschenberg's gigantic oeuvre.

This is why this little essay is presented in six parts and from six different points of view or six themes..

The difficulty is that as far as I can tell, the Cibachromes take as their subjects the commissioned, legal carvings. The urban guerrilla works, the illegal interventions Matta-Clark made in Bronx tenements and a notorious Hudson River pier known as a site for public sex, are subsumed.

* * *

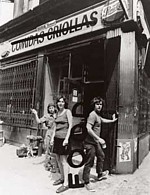

Tina Girouard, Carol Goodeen, and Matta-Clarks in front of Food restaurant, 1971 (courtesy of Matta-Clark Estate and David Zwirner)

5. Lost Horizons

Wallace Berman and His Circle (at NYU's Grey Gallery) stirred my interest in art groups. Reading the catalog for the Matta-Clark exhibition made me wish for a Greene Street exhibition. I don't think Matta-Clark took a leadership role in the early Greene Street days of SoHo, the way Berman did in Los Angeles in the '50s, but there were artists I remember.

Had SoHo even been named yet? Artists I knew and at least one minimalist composer had slide-away beds, hidden stoves, closet showers. It was still illegal to live in those ratty, old loft buildings that now only millionaires can afford.

First there was 98 Greene Street, which was mostly Holly Solomon's theater project, but I remember Thomas Lanigan-Schmidt getting a drag queen in widows weeds to kneel for hours in front of an ornate altar he had made of tinfoil and bangles. Then the artist Jeffrey Lew fronted the 112 Greene Street gallery and performance space. Others in the informal group were Richard Landry, Richard Nonas, Jene Highstein, Suzanne Harris, Roger Welch, Tina Girouard (who was one of the Matta-Clark's FOOD restaurant collaborators), the poet Ted Greenwald, dancer Trisha Brown, and Alan Saret.

6. The Alchemy Problem: Gordon Matter-Clark

One might think that because the early work involved mold and food, the transformation of garbage into art, and the FOOD restaurant, Matta-Clark would be a likely alchemical suspect. Also, rumor had it that Marcel Duchamp was his godfather. Matta pére certainly knew Duchamp. According to the collector Arturo Schwartz alchemy was Duchamp's secret inspiration. We even have lists of specialized books Duchamp may have read when he was working in a library in Paris as a young man.

We already know of this exchange at a Cordier-Ekstrom Gallery opening of Duchamp's oddments:

Robert Smithson: Oh, I see you are into alchemy.

Marcel Duchamp: Yes, indeed.

Matta-Clark, knowing what materialists his heros like Smithson were, denied being an alchemist. However, we now know from Tina Kukielski's oddly titled catalog essay ("In the Spirit of the Vegetable: The Early Works of Gordon Matta-Clark") that books by Jung were in the artist's library, as were books by Ouspensky and Gurdjieff. But didn't everyone in the '60s and early '70s read Jung, Ouspensky, and Gurdjieff? Reading Jung doesn't make you an alchemist. Reading Ouspensky and Gurdjieff doesn't make you a mystic, any more than reading Shakespeare makes you a poet.

Which leads me to the library problem.

If you do not want to leave any traces or clues, get rid of your books before the art historians get a hold of them. This is a new trend: examining the contents of dead artists' libraries. I first became aware of it with the catalog for the 2005 Smithson exhibition and was inspired to write a little essay for Artopia about books and my own library.

So that no one will be mislead and in the interest of privacy, I am seriously thinking of secretly selling off my alchemical tomes; my books by Rabbi Nachman and by Ibn Arabi. My Zohar has long been given away.

And why would anyone be certain that Matta-Clark actually read the Gurdjieff on his shelf? Although I own the Alchemical Writings of Edward Kelly (who had his hand chopped off for thievery and was magus John Dee's right-hand man and skyrying partner), I have never been able to read more than a sentence or two: "But among metals there is no form more vigorous or powerful than that of Saturn, and therefore the solvent of Saturn must be sought in the vegetable world."

By the way, isn't all art about the transformation of matter, turning dross into gold, which in turn is a symbol for personal transformation?

Matta-Clark used a chain-saw to turn bad houses, tenements, abandoned piers, and office buildings into temples---letting the light shine in. Chunks of this architecture may have ended up in galleries and museums, but like the attractive Cibachromes, also on display at the Whitney, we only know the art, which was an action, by the static residue.

Matta-Clark, Day's End (Pier 52), 1975.

FOR AN ARTOPIA ALERT WHEN NEW ENTRIES ARE POSTED

CONTACT: jperreeault@aol.com

ALSO NOTE: Past entries can now be searched; see top right. Also go to: ARCHIVE for retrieval by month or headline.

Two Questions

1. Do artists have rights over their artworks even after they are sold?

2. What is a conflict of interest?

I too read other art critics, but Artopia is not metacriticism. We will leave that for other places. Nevertheless, occasionally I am stirred up. My two questions were generated by reviews that were in the N. Y. Times of Friday, February 9.

Neuberger Museum website "image" for Richard Prince exhibition

Prince Nixes Pix

The first topic is inspired by Roberta Smith's review of the current Richard Prince exhibition at the Neuberger Museum of Art, SUNY Purchase, N.Y. It's called "Fugitive Artist: The Early Work of Richard Prince, 1974-77." I do not fault Smith's opinions of the art. I may await Prince's forthcoming Guggenheim survey in order to get a better grip on why his prices are so high. I was always intrigued by his re-photographing of Marlboro ads, but left cold by his written-out jokes-on-canvas. The car hoods might tip the scale. Maybe then I will understand why the Guggenheim has accessed his upstate house with all contents for its permanent collection.

Prince seems to object to his early works being shown at the Neuberger. He does not own them; they come from various corporate and private collections. According to Smith, Prince previously claimed he had destroyed these mid-'70s pieces; early exhibitions at the Kathryn Markel and Ellen Sragow galleries are omitted from recent Prince tomes. SUNY Purchase professor Michael Lobel has effected the disinterment. The artist refused to allow the works to be illustrated in the catalog.

"It is hard to understand Mr. Prince's disengagement from a respectful show of works he obviously took seriously," writes Smith. "Some are a bit embarrassing, but in the main they increase his stature. Cynics might say he did it to get attention, but in principle he may be right. The unillustrated catalog aside, it could be argued that living artists should always stand back and let curators and art historians do their work."

I'm afraid that's not really the point. The real issue is whether a living artist has authority over the display and the treatment of his or her work. In the E.U., where the legal principle is called Droit Moral, the artist does; here also, but only for work made after 1990.

According to the Visual Artists Rights Act of 1990 (VARA), "a work reflects the personality of the artist and these rights are regarded as personal rather than economic rights. The rights granted under VARA, which are similar to those granted to creators by many other nations, are the rights of attribution and integrity..." (Smithsonian Museum).

Furthermore the Legal Information Institute of the Cornell Law School states that under VARA, "the artist shall have the right to prevent the use of his or her name as the author of the work of visual art in the event of a distortion, mutilation, or other modification of the work which would be prejudicial to his or her honor or reputation."

According to the letter of the law, Lobel and the Neuberger are off the hook: VARA doesn't apply to the Prince works. But in terms of the spirit of the law and in the eyes of Artopia, both the curator and the institution are culpable. You either respect the wishes of artists, or not. We don't want owners of artworks to cut them up to fit their walls, lend them for porn shoots, or use them for ironing boards -- as Marcel Duchamp, at his most playful, once suggested. We would never cede that artists can or should control the interpretation of their works, but while artists are alive, their decision whether to exhibit work or not should be respected.

In this regard, before there was VARA in the U.S. there was a highly publicized incident involving artists' moral rights.

Catalog: The Machine As Seen at the End of the Mechanical Age

Forgotten History?

Several artists in Pontus Hulten's "The Machine As Seen at the End of the Mechanical Age" at the Museum of Modern Art (November 1968 - February 9, 1969) objected to how their works were displayed or maintained. Takis simply objected to where his kinetic sculpture was placed and, if I remember correctly, that it was a small piece from the MoMA collection and not, let's say, something more befitting an acknowledged leader of kinetic art. Hans Haacke - now justly celebrated for his political art -- for some reason did not like that his steam and refrigeration piece was turned off every evening by the guards. The ice that was meant to accumulate simply melted away every night. Wen-Ying Tsai also could not get staff cooperation in terms of his interactive kinetic sound sculpture. No one notified him when it wasn't working, and he was therefore represented by an artwork not fully functional, not really his.

All three artists were used to Droit Moral protections under the Berne Convention. Takis is Greek; Haacke, German; and although Chinese, Tsai had shown mainly in Paris. In 1969, the U.S. had no such law. Looking back, the fracas was a bellwether of globalization disjunctures, reflected in art practice.

But there's more.

Having alerted the press, Takis arrived and removed his sculpture, sitting with it protectively in the sculpture garden.

By this time, a full-fledged artists' group was in formation. Others I remember being involved at the early stages of what became the Art Workers Coalition were Willoughby Sharp (who founded Avalanche Magazine), critic Gregory Battcock of New Art and Minimal Art anthology fame, Benny Andrews (later head of Visual Arts, National Endowment for the Arts), Robert Morris, Les Levine, Tom Lloyd, Dennis Oppenheim, and, of course, the three artists already mentioned. I was also active with the group.

On January 28, our demands, which had escalated, were submitted to MoMA director Bates Lowry, the Director or MoMA. They included: "The museum should recognize an artist's right to refuse showing a work owned by the Museum in any exhibition other than one of the Museum's permanent collection" and "The Museum should appoint a responsible person to handle any grievances arising from its dealing with artists." We also demanded rental fees for artists and the now equally utopian notion of free admission to the museum. We also wanted more work by black and Latino artists shown in the museum.

Those were different times, times of protest against the war in Vietnam, and everyone was unhinged by the assassinations of JFK, then Martin Luther King, Jr. and RFK.

By May of that same year, Lowry was no longer Director.

And later in 1969, the Art Workers Coalition, now a fully formed organization, kept on dreaming up demands such as more exhibitions for women artists...not only at MoMA but in all museums and galleries. Robert Morris and Poppy Johnson were voted in as co-chairs and packed meetings of the Coalition were held at the School of Visual Arts.

MoMA Launches Latin Dud

I have often said that the art world runs on conflict of interest, but we don't like it. There are rules about such things. This second topic is inspired by Holland Cotter's brave Times review of MoMA's Armando Reverón exhibition (through April 16).

After devoting far too many words to describing some totally inconsequential art, Cotter adds the following paragraphs:

MoMA has given solo show to only four Latin American modernists. Why should Reverón be one of them? On the surface at least he exemplifies cultural stereotypes that art historians are trying to move beyond, the Latin American artist as an exotic: instinctual, irrational, primitivizing, in tune with nature, fantasy-driven, "spiritual," indebted to - rather than in control of - European forms.

Artopia agrees.

Maybe there were practical reasons for the choice. Several of the paintings in the show, organized by John Elderfield, chief curator of painting and sculpture at the museum, belong to Patricia Phelps de Cisneros, a MoMA trustee with a fabulous Latin American collection, including the largest number of Reveróns in private hands (The museum's new curator of Latin American art, Pérez-Oramas, who consulted on this show used to work for the Cisneros foundation in Caracas).

Uh-oh.

What I learned during my many years as an employee of several museums and nonprofit art institutions - and through my membership in the American Association Museums - is that there must not be even the appearance of a conflict of interest.

Artopia agrees with Cotter that MoMA's "effort to expand its definition of modernism to include the world" is positive. Artopia, however, would do more than hint that there might be better Latin American candidates for MoMA market approval. Although we are not personally familiar with the Venezuelan art scene, we do know of many Brazilian and Argentine modernists more deserving than Reverón. Contrary to Cotter's kicker, Reverón is not "an artist...you will be glad to know."

Except for one or two all-white beach paintings from the '20s and the painting props for his silly nudes, the work is so banal that we are literally forced to examine the wall labels for hidden agendas. Curator John Elderfield is a Matisse expert, but Reverón is no Matisse.

MoMA's contemporary galleries are now looking good. There's even a David Hammons African-American flag. The theme show "Out of Time" has some splendid work. It, therefore, comes as a shock to see the schlock on the sixth floor.

Kristofer Paetau and Ondrej Brody: ArtForm Accident, 2005

Finally, on a more positive note, I was greatly relieved (if you will excuse the expression) that things in New York are not as bad as in Prague. This I learned from the website of the talented and provocative Swiss art-couple Kristofer Paetau and Ondrej Brody.

Mr. Paetau threw up at the '05 ArtForm in Berlin. This choice piece of art, reflecting my sentiments about art fairs exactly, received 15,000 hits on YouTube. Mr. Brody once set himself afire as an artwork. And the two, when bored by audience taunts that they were nothing but neo-dadaists, recently destroyed their Apple computer and walked off a lecture platform in Berne.

The Paetau/Brody website also includes footage of their so-called Prague Shit-In, held in the Czech Republic National Gallery of Art. Therein, five artists simultaneously relieved themselves on the floor after revelations that the Director had purchased his own artworks for the museum's permanent collection...and at inflated prices.

FOR EMAIL ARTOPIA ALERTS WHEN NEW ENTRIES ARE POSTED CONTACT: perreault@aol.com

Also note: All entries can now be searched. See column to the right.

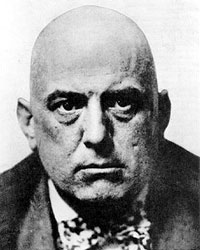

Aleister Crowley, 1875-1947

Once Was Wicked

By the time you read this, the exhibition of elegant, out-there drawings by the infamous Cameron may be closed (Nicole Klagsbrun Gallery, 526 West 26th Street, No. 213, through February 10). I usually post my essays inspired by current exhibitions while said offerings are still available. But this time around I made an exception.

I wanted to beat the New York Times and the Village Voice on the David Hammons show, and I needed time to read through Aleister Crowley's Diary of a Drug Fiend, 1922. Down below, you'll see why.

Crowley's Book of the Law (1904), supposedly dictated by an angel, is available on the Internet. It is a wee bit obscure. Diary, on the other hand, is over the top and entertaining in an appalling way. According to a friend of mine, who should know about such things, it perfectly captures the bliss and then the degradation of cocaine and heroin. The two narrators are, of course, totally unreliable in this modernist or postmodernist romp disguised as a Victorian cautionary tale.

Now, when I see East Village junkies on the street or hopheads in a Target off the L.I.E., I'll know what's going on in their minds, and their lives, and why they think nobody notices their party. Crowley's cure, in the final "Purgatorio" section of Diary, is less convincing, although the list of excuses offered for taking drugs is both hysterically funny and definitive --

From:

1. My cough is very bad this morning.

(Note: (a) Is cough really bad?

(b) If so, is the body coughing because it is sick or because

it wants to persuade you to give it some heroin?

To:

27. ...Suppose I take all this pains [sic] to stop drugs and then get cancer

or something right away, what a fool I shall feel!

I then learned from Roger Hutchinson's level-headed Aleister Crowley, The Beast Demystified (Mainstream Publishing) that Crowley was able to maintain his heroin habit by medical prescription until his death in 1947. Seems he was given heroin in his youth as an asthma cure. As someone once said, physician, cure thyself.

The inspiration for several novels and short stories, magus Crowley once tried to hijack the Golden Dawn brotherhood from poet W. B. Yeats, founded a "religion" called Thelema, and was called the wickedest man in the world. According to his deathbed nurse, his last words were either "I am perplexed" or "Sometimes I hate myself."

* * *

Cameron as the Scarlet Woman

Your Muse Appears

I was more than intrigued by the Cameron (1922-1995) presence in the "Semina" exhibition at the Grey Art Gallery, so seeing the exhibition at Klagsbrun was a given. And sure enough, the art topics just flowed. Topics? Problems would be a better term. Not problems in the negative sense, but problems as in geometry or algebra. The big problem is: Must you separate the art from the artist? Can you?

I need to confess that after seeing Curtis Harrington's short film The Wormwood Star (1955) in the Klagsbrun Gallery, I was hooked on Cameron's image. She is shown in her studio among her now lost or destroyed artworks reciting some of her writings. Even on the gallery's small monitor, she dominates the room, the gallery, the building, the block, and all of Chelsea. Not all of Manhattan, mind you, but certainly all of Chelsea.

So I rented "cult director" Harrington's full-length fiction-feature Night Tide (1961). The young and handsome Dennis Hopper plays the sailor in love with...I won't be a spoiler. Let us just say that the object of his attraction makes her living by sitting in a tank of water on the Santa Monica pier. Cameron plays the mysterious woman calling back the heroine to her watery roots. We do not remember Linda Lawson's Mora, but we certainly remember Cameron's Water Witch.

Then, being a scholar, I had to rent Kenneth Anger's Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome (1956), in which Cameron, as the Scarlet Woman, upstages Henry Miller's onetime paramour Anais Nin. Yes, Anais Nin.

The film, which involves a lot of posing, posturing, and the swallowing of necklaces and gems, builds to a ritualistic climax of luxurious superimpositions. These days, it does seem, alas, like stoners playing dress-up, but Cameron burns a hole in the screen. Aside from wearing a cape once worn by Rudolph Valentino, she is almost too real. She was certainly not afraid of using lots of eye makeup and staring right into the camera with those lucid eyes.

After Cameron's marriage to rocket scientist Jack Parsons (whose "working" he thought had summoned her), our art witch spent some time in a Swiss convent and then the arty Mexican village of San Miguel Allende, where she met Leonora Carrington, the surrealist painter. Co-curator Michael Duncan, who wrote the informative Klagsbrun catalog essay, sees Cameron's art as related to Carrington's.

Cameron returned to Parsons. I guess the art colony in San Miguel was too rarified. In 1952, Parsons, a disciple of Crowley, was killed by an explosion in his garage -- an explosion that is usually called "mysterious." How could an explosion be "mysterious" in comparison to trying to make an homunculus using the Enochian calls of the Elizabethan magus John Dee?

I dare not tell you what science fiction author, in the "Babalon working," played Edward Kelley to Parsons' Dee.

After Parsons died, Cameron "retreated to the desert of Beaumont, California for a kind of 'vision quest,' living for a while in an abandoned canyon without water or power," reports Duncan.

We have already related the tale of Marjorie Cameron's 1955 tangle with the L.A. police over her "lewd" peyote-inspired drawing. She and artist Wallace Berman vowed never to show in a commercial art gallery again. Later she torched a lot of her work and then made it known that she did not want what remained shown until after her death.

So with a life like that, how can we look at the art? Well, tenderly, cautiously. Perhaps Parsons' 1946 desert ritual worked. After World War II, the empowerment women gained through serving in the war effort lingered and slowly began to flower. The women in post-war noir emblemized men's fear, but the so-called Scarlet Woman could not be stopped.

Cameron, Crucified Woman, n.d.

The angels and demons in Cameron's trippy drawings release a perfume we have not experienced before. Certainly not in the academic surrealism of Carrington, whose charm has always escaped me. The surrealist Pope Andre Breton flirted with occultism. Cameron lived it.

Cameron's drawings, now coming slowly into public view, are in some ways outside art. They are about the power of the images rather than the forms. They resonate with the art of the insane, the drug-addled, the homeless outsider, and perhaps the visionary art of someone like William Blake. Her demons, angels, and horny women are almost too Goth to be true.

Now ye shall know that the chosen priest & apostle of infinite space is the prince-priest the Beast; and in his woman called the Scarlet Woman is all power given. They shall gather my children into their fold: they shall bring the glory of the stars into the hearts of men.

-- Aleister Crowley, The Book of the Law.

Cameron, Untitled, n.d.

IF YOU WISH AN E-MAIL ALERT FOR FUTURE ARTOPIA ENTRIES CONTACT:

perreault@aol.com.

David Hammons, Bliz-aard Ball Sale, 1983

Paint It Black

The reclusive "genius" David Hammons is showing terrific new work. It's right up there with his snowball piece, his rock haircut, his African-American flag, his dark and empty gallery. His current provocation is at L & M Arts, 45 East 78th St., through February 28.

I hesitate to tell you what's in the show since it was the surprise of it that initially turned my head. But you might as well know.

Six fur coats.

Six luxurious fur coats presented on headless manikins in big, empty townhouse rooms, as if on display in a minimalist Upper East Side shop.

Here there's woodwork and polished-wood floors of the best kind. Yes, this is the way galleries used to be, before Soho and before Chelsea introduced the reverse snobbism of sealed concrete floors. When you try to enter the elegant L & M space, a discreetely uniformed guard opens the door. He's surprisingly friendly. Good casting.

The first room is empty, and you might think that this is the lit version of the great Concerto in Black and Blue that Hammons perpetrated in the cavernous Ace Gallery way back in '03. Viewers negotiated the pitch-black rooms with tiny blue-bulb flashlights. But, no. In the second room we are confronted by fur coats that have been modestly streaked with paint.

Later I'll find out there's another coat, as the security man accompanies me upstairs. Guess the bottom line is that no matter how I dress up for my uptown forays I always look slightly suspicious. The lonely, lovely chinchilla upstairs has been attacked with a blow torch.

Are the fur coats meant to be worn? I doubt it. As artworks they are probably too expensive to wear. But there isn't even a price list. How on earth am I going to write about this show?

* * *

Are there any photographs that I can use for Artopia?

I am afraid not.

Can I take my own?

We'll have to call David. He didn't even provide us with a checklist.

Good luck, I said to myself, knowing that the artist avoids telephones

It's all so fresh, don't you think? Compared with what we usually show.

Well, not exactly. You did show Yves Klein.

Yes, that's true.

* * *

Hammons, African-American Flag, N.D.

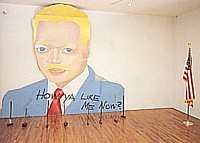

Like Hammons' 1983 streetwork in which he offered snowballs for sale; like his sculpture made of discarded wino-wine bottles; like his sculptures made from hair swept from Harlem barber shops; like his representation of Jesse Jackson as a white man ("How Ya Like Me Now?"), the fur coats are blunt, but surprisingly multivalent. His use of barbershop hair was more than a black artist making a black identity statement and his African-American Flag more than a Black Power joke. Likewise, his new fur coats are more than an anti-fur diatribe, if they are indeed that. I remember when animal activists used to go around spray-painting mink coats worn by ladies emerging from department stores, museums, and churches. But I also remember pre-PETA times when art collector and fur designer Jacques Kaplan issued a line of painted furs.

Given the Upper East Side showcase and his use of paint, could Hammons also be saying that art is the new mink coat?

Further Thoughts, More Contexts

Does Hammons play the art game by his own rules, or is he only playing it with a slight twist? If you really don't want to have anything to do with the art world then you should never show your work in an art gallery or a museum. Period.

I found this 1986 quote attributed to Hammons:

"The art audience is the worst audience in the world. It's overly educated; it's conservative, it's out to criticize and not to understand, and it never has any fun. Why should I spend my time playing to that audience?"

Well, David, the art audiences wasn't overly educated in 1986 and it isn't overly educated now. Furthermore, the art audience always has fun. It's the artists who mope about. Spending money on art is fun; competing with other collectors is fun. Go to any art fair and see.

On the other hand, artists need the art system to distribute and preserve their art, otherwise the art is just personal ritual. Personal ritual and its residue might be a higher form of what now passes for art, but there is no real way of proving this. Masterpieces need to be seen. And in any case it is generally agreed that art is a form of communication and/or research.

And, oh, yes, art is about art.

Hammons, How Do You Like Me Now?, 1988.

The Hammons M.O.

He is unreachable by telephone. Through an intermediary he might agree to an exhibition but he doesn't reveal what the art might be. This means, from his point of view, no one can control or inhibit him and he has the upper hand. On the other hand, he takes the risk of operating without a net. There is no feedback. No one can say: Hmmm. Mr. Hammons, maybe X is not one of your best ideas.

Judging by the catalog to a 1993 exhibition called "David Hammons, In the Hood" at the Illinois State Museum in Springfield (his birthplace), he might have just this once profited from some curatorial expertise. In the Hood and Six Sisters, consisting of five white slips affixed to a wall, and Basketball Drawing, made by bouncing a basketball off the wall around a sacred heart emblem, look great. Middle Passage, using gold necklaces, is too explicit, as is the elaborate installation called Spitting Image.

We see demonstrated in the catalogue how the curator-of-record of the Springfield show (Robert Sill) struggled to accommodate Hammons' practice. Thrift shops functioned as art-supply stores and the artist came with a bag of goodies, probably including the red, black and green Flag. The Jesse Jackson billboard image - which must have been shipped from somewhere -- was probably as startling in Illinois as it was in D. C., but the brand-new Rosa Parks billboard ("Thank you, Sister Rosa Parks"), situated outdoors, seems banal, even in Abraham Lincolnland, no matter how fine the sentiment...

I once thought I had Hammons in my clutches, having written about his Harlem hair sculptures first seen at the Just Above Midtown Gallery and then in April Kingsley's pioneering "African-American Abstraction" exhibition at P.S.1.

It was 1985 when he was in Creative Time's "Art on the Beach" at the sandy site that was to become Battery Park City. His The Delta Spirit House (done in collaboration with Angela Valeria and Jerry Barr) had to be disposed of at the end of the exhibition run.

I honestly can't remember how I got hold of him or if he called me - which is hard to imagine. Nor can I remember if it was his or idea or mine to float The Delta Spirit House across the harbor and down the Kill Van Kull, and then set fire to it in front of Snug Harbor. I was then the Snug Harbor Cultural Center Director of Visual Arts. I remember thinking this Viking funeral would be a good way to salute Robert Richard Randall, founder of Snug Harbor, and also the "aged, decrepit and worn out sailors" who passed their final days watching the tugs go by on the Kill.

It never happened. We lost touch.

Hammons, Haircut, 1992.

Resistance Can Become Existence

Hammons is walking a tightrope, trying to have it both ways. Appearing to be going his own way and yet dependent upon the art world, as every traditional, albeit Duchampian, artist must be. If he doesn't play ball he risks more and more unauthorized retrospectives just like last year's show of photocopies and computer printouts at Triple Candie that received so much press. Such is the Hammons magic that many think he himself was behind the sampling. Was he? Makes no difference, I say. Or: wouldn't put it past him.

He has, however, survived the '80s and the '90s, which is saying something. That half a million from the MacArthur Foundation might have helped.

My theme, in case you haven't caught on, is resistance to the art world. Some now refer to the art world as Moloch. You can indeed be eaten alive. I can hear the chorus now: as if I should be so lucky! Some of us are sleepers, some of us are double-agents. Nevertheless, the art world, with its smiles and deals, is the monster we love to hate, is us.

FOR AUTOMATIC ARTOPIA ALERTS WHEN NEW ESSAYS ARE POSTED:

CONTACT: perreault@aol.com

Also note that the new search function allows you to search all previous entries/

AJ Ads

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Exploring Orchestras w/ Henry Fogel

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary

Tyler Green's modern & contemporary art blog