Artopia: January 2006 Archives

Carolee Schneemann: Meat Joy, 1964

A Living Legend

Performance Art - that is, Performances, Events, Happenings, nonmatrixed artists' theater (in Michael Kirby's excellent term) - are not plays, dances, or operas, although they may partake of some characteristics of these, particularly in that they occur in time with a person or persons as the presenter(s). Like plays, dances, or operas, performances are very difficult to write about. There is usually not a script or much of one and, to recast Kirby, the performers are pretty much themselves (though types crop up, even gods and goddesses if the artist is not careful). The place is here, the time is now. Words may be spoken, but they are rarely central. Most often - and I think ideally - the artist is the "actor," but not necessarily the only one, and everyone isn't acting but being.

Performance-type art is almost impossible to write about because it is so -- well, I have to say it -- ephemeral. Unless we have actually seen the damned things and have very good memories to boot, what we write and say about Performance Art usually has to do with written and oral accounts and, of course, photography and movies. The latter, of course, is in itself also difficult to capture in words.

There are even some Performances or Performance-type artworks that dispense with the immediate audience entirely in favor of the one mediated by the camera. I am thinking of the many of the early street and body works of Vito Acconci and certainly most of the body works of Ana Mendieta. It is not that their bodies became sculptures, but that images of their bodies did. I don't want to be a purist, but there is some sense that if you know a Performance only through photos and maybe videos and/or film, you know only these photos, videos or films.

The recent efforts of Marina Abramovic to perform the Performances of others -- although I believe there is a Fluxus precedence for this -- is a partial solution. Fluxus events, like most of Yoko Ono's instruction pieces (but unlike her Cut, in which the audience is invited to cut off her clothing), do not rely on the artist's presence; theoretically they can be done by anyone. Also, in trying to imagine Abramovic's Entering the Other Side at the Guggenheim performed by someone else, I can only imagine a piece-about-a-piece, or else, like her version of Beuys' How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare, a farce.

I once perpetuated a series of performances (and related street works) myself, so as well as observing a number of these, I have an inside insight. And I have also been an actor in some small way (playing Vincent van Gogh on Dutch television). There is, I can attest, a difference between holding your own, becoming a living sculpture in front of an audience, and playing a role -- forgetting for the moment that being an artist (or a poet or an art critic) is also playing a role.

When, however, do you move from being yourself to being a type? More to the point: when do you move, if ever, from being a type or a personification to becoming an archetype?

I suspect you can tell when you are an archetype when people find meanings in everything you say, in every move and turn of events in your life, meanings you did not exactly intend. You become a mirror for the needs of others. The scary part is that it can happen without your knowing it. Here's an example. I remember that an older poet (Kenneth Koch) in a workshop I was taking stated very clearly that the whole universe was a vast machine for the creation of poems. I thought, as a young poet, that was the most inspiring thing I had ever heard. Years later I told him at a party that one statement of his had influenced me more than anything else. He said he had never said such a thing. Why on earth, he asserted, would he say such a thing that was so preposterous and pompous.

In her earth/merge body sculptures, Mendieta was, I think, consciously playing with archetypes. Andy Warhol, probably through no fault of his own, became one, at least in the eyes of Valerie Solanas, who shot him as the personification of the evil demiurge.

But let us just say that Schneemann, if not an archetype, is at least a living legend; this is primarily because of Meat Joy (1964) and Interior Scroll (1975).

* * *

Scheemann: Interior Scroll, 1975

Our Goddess?

Before there was Abramovic, before there was Hannah Wilke, before there was Mendieta, there was Carolee Schneemann. I know for a fact, having been a friend of hers (also her teacher in Iowa State University), that Mendieta acknowledged Schneemann's influence. Schneemann probably influenced some male artists: Acconci, in his classic Body Art phase, comes to mind. But who was an influence on Schneemann? Antonin Artaud! The collage paintings would indicate de Kooning and Rauschenberg. The performances might lead you to suspect Kaprow, Rauschenberg, and in some cases Hermann Nitsch. But who is to say? I mention these men because I can think of no woman artist that might have been an inspiration.

Schneemann herself has been under a kind of anti-essentialist feminist cloud: it is not exactly accidental that male artists within the Dada/ neo-Dada./post-Fluxus fold have referred to her as Our Goddess. Although her art and her writings are not directly essentialist, she has a Goddess aura. I can remember a time when anti-essentialists feminists disparaged both her and the late Wilke (another beauty) as pandering to the male gaze.

There is, however, not much to be served in re-rehearsing these now ancient feuds between the essentialists and social constructionists among us. If you are not a woman, the only way you can relate to the conflict is by translating it into another form. Is there an innate maleness to heterosexual males? A gay essential to gay males? No. Or is gender totally socially constructed, a product of the environment and culture? No. Language interferes with reality.

Well, that's all over. And we can begin to look at Schneemann neither as exclusively a Goddess nor as an art world pin-up, but as a serious artist. And although the line of expressionist, body-centered women's performance may have temporarily come to a halt, it will never be seen as merely a small incident in art history. If it takes a man to say it, then so be it. The conservatives in politics (and, alas, in art) may have gained some modicum of control, but we will not have women held back by fear of their own bodies.

If there is a level of the mythic in Schneemann's work and persona, then why can't we accept this in the same way we accept the mythic in Joseph Beuys? Men will just have to accept - and this is very difficult - that if you have to have a Goddess, she is also going to be poet Robert Graves' scary White Goddess. Sex is sacred. Well, sort of. In a world that is disastrously overpopulated, it is fortunately also entertainment.

Now on top of all of this, Schneemann has never been shy about the political, either. Her rage at the atrocities in Viet Nam was early: her film Viet Flakes (1965) is still powerful and, alas, pertinent.

* * *

Why She Reigns

Some of these thoughts are inspired by an exhibition of mostly photo-pieces by Schneemann now at P.P.O.W. (555 West 25th Street, to February 11). It is by no means a retrospective, but several pieces effectively recall Schneemann's import. There are no photos of her Kinetic Theater masterpiece Meat Joy (1964) that utilized nudity, paint, words, projections, songs and raw fish, chickens, and sausages. But a new edition of the photographs that compose the 1963 Eye Body: 36 Transformative Actions documents her seminal Body Art efforts. The photos were taken by Icelandic Pop artist Erró. Also, in the form of painted-over and scribbled stills of Interior Scroll (1975), that radical work is documented. In Interior Scroll, naked, she slowly pulled a long paper scroll from her vagina, reading the words: "if you are a woman (and things are not utterly changed/ they will almost never believe you really did it/(what you did do)/ they will worship you they will ignore you/ they will malign you they will pamper you/ they will try to take what you did as their own...." I am copying this from the text in Carolee Schneemann: Imaging Her Erotics (MIT Press).

Viet Flakes is also part of the exhibition, as are Hand/ Heart for Ana Mendieta (1986) based on a dream she had about Mendieta right after her death caused by "falling" from an apartment house window, and Terminal Velocity (2001), altered newspaper photos of bodies falling from the World Trade Towers. Difficult stuff.

Thanks to the Muse (God or Goddess) of art criticism, you can see the actual Schneemann Scroll as part of Carlo McCormick's jazzy and inclusive The Downtown Show (The New York Art Scene 1974-1984). Compare this if if you dare the New Museum East Village show in 2004. The new survey is through April 1, at NYU's Grey Art Gallery (100 Washington Square East) and the Fales Library, (70 Washington Square South) where there are works by Mendieta and Wilke. The Scroll is part of the Library branch of the exhibition. Be forewarned: both the Library wing of the exhibition and the piggy-backing design show called Anarchy to Affluence at Parsons/New School are not open on Saturdays. The NYU show received funding from the Andy Warhol and Robert Mapplethorpe Foundations and the New York State Council of the Arts; especially in light of the latter, shouldn't the Fales addendum be open to the public on Saturdays? Or is it only for students, who, I guess, disappear on weekends?

Superflex: Guarana Power (display of Guarana soda)

Riffs on a Global Groove

I was in Tennessee just recently to give a little talk at the brand new Art Gallery of Knoxville, where until the end of the month there’s an exhibition called “Global Groove (Nation Building As Art).” It was curated by director Chris Molinsky. Molinsky, Leslie Starritt, and Bryan McCullough (all recent graduates of the Art Institute of Chicago) are cofounders of this bright new space, which opened in November. My theme, in honor of "Global Groove," was art globalization.

Internationalism is not new. There was Zurich Dada, Berlin Dada, Paris Dada, and New York Dada. According to situationist Vaoul Vaneigem (in his vituperative, mostly anti-Surrealist textbook called A Cavalier History of Surrealism, AK Press). there were surrealist groups in Romania, Yugoslavia, Czechoslovakia, Scandinavia, Belgium, Italy, South America, the Canary Islands, Mexico, Japan, Haiti and, of course, Paris, where it all started.

The New York School – i.e., Abstract Expressionism – included the Russian-born Mark Rothko, Hans Hofmann from Germany, Arshile Gorky from Armenia, Willem de Kooning from the Netherlands, and Matta from Chile.

But globalism is something more than internationalism or even cosmopolitanism. Even yours truly has traveled far and wide in the service of art: Australia, Brazil, Finland, Germany, Iceland, Israel, Italy, Japan, New Zealand, Norway, Ponape in Micronesia, Sweden, Tahiti. And as an artist I have recently exhibited work in Berlin, the United Arab Emirates and Beijing.

Artopia, of course, covers the world. And thus we get closer to globalism as a culture superimposed upon and perhaps superceding all national subcultures thanks to the internet, our new hope.

The title “Global Groove” comes from video pioneer Nam-Jun Paik, whose thoughts from way back at the beginning of McLuhan’s Global Village – to which he opposes the Global Groove ---can be found on theArt Gallery of Knoxvillewebsite. You have to search for it a bit, but clicking on a rainbow of little buttons will yield Paik’s essay and many other goodies, such as all you need to know about the kingdom of Elgaland -Vargaland, Superflex’s Guarana project, etc. There is alsoa video podcast of my well-attended talk.

In the meantime, suffice it to say that in my talk I could not help but entertain the dark side of globalization, investigating if there is a connection between art globalization and corporate/pop culture globalization. There is, let it be said, the ever-present danger of global uniformity. After a while, one installation looks like any other; one motion picture projected on a gallery or museum wall is just a representation of other projected motion pictures. If art globalization must be separated from corporate globalization, perhaps this can be achieved by using art as immunization against globalization, or as an infection that is spread by economic globalization.

The way I see it, there are two parts to “Global Groove”: representations of various global or borderland projects in the gallery itself, and a website manifestation that demonstrates global themes.

The official flag of Elgaland-Vargaland

How Global Is It?

As a critic, artist, and poet I have long been interested in borders, borderlands, or what could also be called thresholds: not only between nations, but between genres (poetry/prose, painting/sculpture, philosophy/dance) and between disciplines (poetry/criticism, art/philosophy).

As the ongoing Artopia text is to normal blogs, my more complicated investigations are to Artopia. I have been reading an extremely academic book called Ghazali and the Poetics of Imagination (University of North Carolina Press) in which author Ebrahim Moosa, who was born in South Africa but was impressed by a major text by al-Ghazali in his youth in Bombay, emphasizes the importance of the threshold (dihlîz) in Gahzali’s thinking. This is perhaps best emblemized by the threshold between the oral and the written, between jurisprudence (of all things) and mysticism. Al-Ghazali (1059-1111) is by all accounts one of the great world-thinkers – he is sometimes considered the Thomas Aquinas of Islam, but in his later, post-Aristotle phase he became a Sufi giant.

The Art Gallery of Knoxville is itself a threshold, in that it occupies a borderland between physical gallery and website in much the same way that Philadelphia’s Slought Foundation does. Slought, which we may visit at some other time, has been in existence since 2002 and consequently has a big archive of lectures and panel discussions on its website: Slought. But hold onto your hats; here comes Knoxville. Links become both the catalog of the physical exhibition and an online exhibition in itself.

Tennessee itself is a borderland occupying a new territory between the Southern and the postmodern. Knoxville is associated with the Tennessee Valley Authority. That huge project involving the damming of the Tennessee River and the sometimes needless destruction of farms, created cheap hydroelectric power. If that were not enough of modern culture, there is the “secret city” of the Oak Ridge Laboratories that had so much to do with the creation of the atomic bomb and atomic energy. Tourists can now take train rides through the Oak Ridge “secret city,” but touristically it does not rival the nearby Dollywood (Dolly Parton’s theme park. Oak Ridge may have slightly more significance. Maybe not.

Knoxville sports a huge university – sometimes referred to as The Fort (which tells it all) – and a downtown in the throes of revival. The handsome, compact Edward Larabee Barnes-designed Knoxville Art Museum, overlooks the site of the 1984 World’s Fair – which is the border between the University and Downtown.

The Art Gallery of Knoxville is located in downtown Knoxville at the north end of Gay Street, the present art gallery row. Unfortunately, the month the Gallery opened, the city tore down the bridge connecting South and North Gay Street and spanning the freight-train tracks. Not to fear; the Gay Street Viaduct will be rebuilt. In the meantime, The Gallery, proudly proclaims cofounder Starritt, is in No Man’s Land. It is even a number of block from the Old Town saloon scene, where many a country-music star had been known to drink to excess. There is a boulder by the Tennessee River, someone tells me after my lecture, with the ancient inscription: “now I know why the devil made Knoxville.”

The Gallery is modest but elegant. One side of a double storefront houses the exhibition module, which is basically a freestanding, 15-foot plywood cube with the top and front removed. You can walk around the outside and see the beams and nails, but the inside is gallery-finished. If anyone wanted to book a show out of the Art Gallery of Knoxville, the exhibition space could be easily and precisely duplicated. The other half of the double storefront is used for Wednesday night public events and has a table with books for sale, paintings up on the wall, and a TV monitor.

There’s a lot of video in Molinsky’s complex, clever “Global Grove”; little screens on microphone stands in a forest of potted plants show, for instance, Valery Grancher’s “The Shiwiars Project” documenting a remote Amazon village. A nearby wall-mounted monitor screens Phill Niblock’s The Movement of People Working – no plot, no comment, but long takes of people making things in Mexico and Peru, with the composer’s drone music as background. Also shown: Gordon Matta-Clark’s (1974) video documentation of “gutterspace” in Queens, useless slivers of land put up for sale by the City of New York.

Having been to Brazil (only Rio and Sao Paulo), I was much taken with Superflex’s Guarana Power: worker-harvested guarana, used in soda, bottled in Denmark. Guarana essence is the operative speed in the Brazilian national soda-pop . The “myth” I heard in Rio was that Coca-Cola was buying up the guarana plants to prevent it becoming a rival, since, as Cariocas can testify, guarana pop has a bigger buzz. And, from Sweden, CM von Hausswolff and Leif Elggren’s Elgaland-Vargaland (represented by the Elgaland-Vargaland flag and a case full of stamps and other “ephemera”) is droll indeed. Elgaland-Vargaland is made up of all the existing borders between countries; you can apply for citizenship online.

Here we must note that there is a long history of imaginary countries. The French critic Pierre Restany had his own nation, complete with postage stamps. Artopia, of course, is transnational, but not a country per se. It is instead a state of mind, an imaginal domain that supersedes lesser realities. No postage stamps or flags are necessary.

On The Art Gallery of Knoxville website you can find an essay from a recent issue of Cabinet magazine dedicated to “fictional” countries. This leads me to the website part of the exhibition. Beware. It fans out into enormous alleyways and pathways. The Superflex site is particularly seductive: there’s more than soda and a lot of Fluxus and links to fascinating videos.

Are we therefore closer to website exhibitions without any physical manifestations? Not yet, but perhaps soon.

"Global Groove" video display (partial).

* * *

Thresholds of Past and Present

I gained a lot by traveling to Knoxville. Not only was I reminded about how annoying air travel can be, but I also got another glimpse of the Smoky Mountains. Ten years ago, involved in a project for the North Carolina State Arts Council, I visited the Smoky Mountains to visit the charming John C. Campbell Folk School near Brasstown, on the North Carolina side. Founded in 1925 by Yankee do-gooder Olive Dame, the John C. Campbell School (named after Dame’s deceased husband) was one of several help-the-Anglo, help-the-Aryan, Elizabethan English-speaking, mountain-folk projects of the period. These were no doubt well meant but possibly a Wasp response to new waves of non-Wasp emigrations in big cities. Arrowmont, Penland, and the Southern Highland Craft Guild are others.

Promoted in tourist brochures as “the world’s oldest mountains,” The Smokies feel old and haunted; they certainly are worn-down and rolling. Walking along a misty, woodland trail (I kid you not) I heard a strange sound, neither thunder nor a hundred woodpeckers attacking plywood, but something in-between. I followed it off the path. It was not the ghosts of the Cherokees, on their ghostly Trail of Tears. There on a wooden platform were a score of mountain teenagers in pseudo, feed-bag calico and woolen plaid, going through their ancient Anglo-Irish clog dance numbers, all apace, all in sync, wooden soles in perfect time. It wasn’t exactly a raga rhythm, but it wasn’t simple marching time, either. It was the birth of tap.

Of course, Knoxville Gallery co-founder Starritt (the only Tennessee native of the founding threesome), whose family’s farm was wiped out by the TVA, also spoke of the still existent poverty and cultural isolation of Appalachia.

Appalachia! Now there’s another country; it snakes from the Smokies and the Blue Ridge Mountains to, if you are to believe the Appalachian Trail, the wilds of Maine. And it isn’t a made-up place, although it may in part still be a fantasy. The gift shop in the Knoxville airport sells moonshine jam. But moonshine itself is now marketed nationally, in Mason jars.

For Artopia Alerts when new essays are posted

e-mail: perreault@aol.com

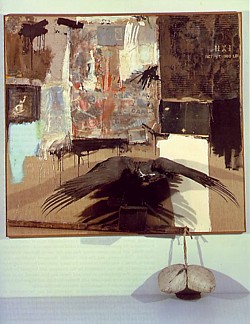

Robert Rauschenberg: Monogram, 1955-59

The Poetry of Things

If you have never seen Robert Rauschenberg's iconic Bed (1955), Canyon (1959), or the free-standing Monogram (1955-59),or have some pressing need to see them together amid a number of lesser Combines, then you had better visit the current exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (until April 2).

You had also better see the exhibition if you really want to challenge yourself with questions of connoisseurship, art history and art criticism. The $45 paperback catalogue will no doubt explain the autobiographical and formal import of the artist's signature stuffed animals, paint splashes and slashes, news photos and poster lettering. That may get you out of Port Arthur, Texas (birthplace of both Rauschenberg and, a bit later, Janis Joplin), but it won't get you out of the good old days in Lower Manhattan, when Jasper Johns was Rauschenberg's neighbor, and more, when images from Life Magazine and Time became fair game, and when Abstract Expressionism, then in its woeful second generation, was faltering.

Complaining about the pomposity in sway at the Cedar Bar and The Club, Rauschenberg told Calvin Tomkins (Off the Wall, Doubleday, 1980):

"They even assigned seriousness to certain colors," and then, turning to the way the New York artists had infected Beat poetry: "I used to think of that line in Allen Ginsberg's Howl, about 'the sad cup of coffee.' I've had cold coffee and hot coffee, good coffee and lousy coffee, but I've never had a sad cup of coffee."

I have always found that a strange quote. Rauschenberg is known to be a generous man, not only to other artists, but to dancers and choreographers and even to poets. Heat one point turned over the chapel in his Lafayette Street building, once an orphanage, to John Giorno, Michael Benedikt and myself to produce one-night poetry performances. In the dark, taped poems booming, I inflated a giant weather balloon with helium so that it loomed above in the rafters; I also did my Whisper Event, whispering a one-line poem into individual ears of all and sundry.

I think there has always been a strain of poetry in Rauschenberg's art, maybe not the sad and mournful kind, but the exuberant, even prophetic kind. This is, after all, the man who spent a whole year making illustrations for Dante's Inferno. Is he against metaphor? Or against interpretation? Or just against bad poetry?

Robert Rauschenberg, Canyon, 1959

An American Picasso

Made from approximately 1954 to 1964, the Combines present mostly two-dimensional found materials held together with splashes and drips of paint, plus here and there the addition of 3-D objects. The bed that makes up Bed was Rauschenberg's own, complete with pillow and quilt; Canyon combines an eagle and a pillow; Monogram features an Angora goat with its head through a rubber tire. These are all masterpieces. What other artists were doing or would do to extend the collage tradition into three dimensions was called assemblage. But Rauschenberg likes the term Combine, which he himself coined. He claims he was inspired by Calder's use of the term mobile, invented to put people's minds at ease. If you can give something that warps categories a name, then you have dispelled fear and perception becomes possible. The mobiles, as we know, are hanging sculptures that move, and the principle and the name is now used for mass-produced Day-Glo toys for every crib.

The Combines are both painting and sculpture-- or, some purists would say, neither. They are best when they are least flat, which is why the silk-screen paintings that followed -- in some ways products of Rauschenberg's success, which allowed him to spend more money on materials -- are not as interesting. Whether carefully considered or spontaneous, the Combines profit by their ad hoc aura, their found-art, apparently free-wheeling joy. No art is worth much unless the first reaction is "anyone could do it." Well, as usual, it turned out that not anyone could make a successful Combine; in fact, many times -- as proved by this gathering of Combines -- even Rauschenberg couldn't.

This is where connoisseurship comes in, or even art criticism. What makes one Combine a masterpiece and another, in the same room, just some meaningless stuff? I became an art critic to find out how to be an artist and how to make art. One principle is that great artworks are iconic, and they begin that way. In an unguarded moment, an artist friend once blurted out that an artwork did not exist unless it could be photographed. My refinement would be: unless it is photogenic. But just so we don't get too wrapped up in media and Pop Art, let us finally say instead that an artwork has got to be memorable, which thereby allows conceptualist as well as predominantly visual artworks. Rauschenberg's prime Combines stick in the mind; they surprise and keep on surprising.

Alas, not many of the Combine paintings are particularly "photogenic." But they do that picture-plane trick that critic Rosalind Krauss tries to talk about in her essay for the 1997 Guggenheim retrospective, making Rauschenberg seem like a latter-day Hans Hofmann determined not to violate the picture-plane. She was right. He respects the picture plane, but by putting things in front of it.

The art criticism consensus has been that, no matter how much one might be attracted to this or that silk-screen painting or technological folly, the Combines are Rauschenberg's highest achievement, so I was excited about seeing a big batch of Combines all together. But the first thing I learned as I walked through is that Rauschenberg was as indiscriminate in his Combines as he was with his silk-screen paintings. However, when he hits with the Combines, he hits with a big bang. Maybe this is why we should not dismiss the silk-screen paintings, or the technological works, just yet.

Has anyone ever counted how many really boring or uninspired paintings Picasso made? Like Picasso, Rauschenberg has been an art machine; just keep the wheels rolling and sooner or later inspiration will strike. And it will probably take others to tell you when it's really happened. How unlike the Duchampian constipation-mode of creation. Another rule for art: You gotta have product; lots and lots of things to sell.

And then it dawns on you that the curatorial lack of discrimination mirrors Rauschenberg's own system. This is not good. The current exhibitionis an awfully expensive way of finding out that the Combines do not form a consistent body of work. But given Rauschenberg's wild manner of making art, should we have expected otherwise?

When confronted by so manyCombines all thrown together, the majority being more-or-less flat, the tiniest of squints will reveal that what you are really looking at is outsized Late Cubism. After all, assemblage is an offshoot of collage. But then you have to ask yourself, is Cubism wrong?

Rauschenberg's Combines and silk-screen paintings areas faceted as classic Cubism, presenting multiple points of views -- not of one still-life, but of life itself, through the use of photos, words, objects of differing scales and degrees of detail. There is no bowl of apples, no face, no café wine bottle, no pipe you need to decipher. It is perception itself (and its intermediaries) you need to read.

It may be too soon to judge Rauschenberg's silk-screen paintings, but I am not reluctant to announce that the all-white paintings of 1951, the 22-foot automobile-tire print of 1953, the erased de Kooning drawing of the same year, the Combines mentioned above, plus Factum I and II of 1957 (in which Rauschenberg duplicates a spontaneous Combine painting) are great artworks worth seeing and thinking about. Of the technological works, I'd vote for Soundings of 1968, and Mud Muse of '68-'71. And I am not the only one to think that the cardboard box wall-pieces will look better and better as the years go on.

But Rauschenberg's most lasting contribution may be his nerve. All-white paintings? You bet. Stuffed birds? Why not. Performances? Of course. Art and technology? Sure. He has never been embarrassed by his own lack of decorum.

* * *

To repeat the rules, you have to produce icons and you gotta have product; lots of it. But to become a successful artist, it also helps to invent a new term -- like Found Art, mobile, or Combine. Furthermore, you are required to produce at least one good quote, like Rauschenberg: "Painting relates to both art and life. Neither can be made (I try to act in that gap between the two)."

FORE-MAIL ARTOPIA ALERT WHEN A NEW ESSAY IS POSTED CONTACT: perreault@aol.com

AJ Ads

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Exploring Orchestras w/ Henry Fogel

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary

Tyler Green's modern & contemporary art blog