Artopia: November 2005 Archives

Abramovic: How To Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare, 2005.

Notes on Performance Art

Conventions rule. The iron hand of custom, as outlined last time around, keeps the art world under control. We must have art that stays the same for each visit, over time. We must have catalogues. And catalogues cannot be written about art before it exists. Biographies and pictures of previous works are not quite the same thing as a thorough, thoughtful analysis or...postmortem.

The ephemeral, both in museums and in galleries, is suspect. Both writers and readers are at a disadvantage: unless the event is repeated, any review or essay cannot be checked against the art. The art is only a memory. Besides, who is going to buy a performance, and, if so, what would you buy? A photo? Or some horrible videotape or DVD that in itself won't last? And what could be more ephemeral than performance art?

Performance art takes place in space (sometimes a specific space) and time (usually a specific time, time being a material too). At its most pure, performance art is executed by the artist. The body at hand is the sculpture.

We are left with photographs and words. Or moving images, none of which are quite the same as the....what? Boredom? Fear? Titillation?

Like theater because there is a person and an audience, but unlike theater because the person is not pretending to be someone else, the most rigorous performance art eludes art history and, apparently, art criticism. But then again, both art history and art criticism are dependent on goods, both fresh and preserved.

In the '50s and '60s it was enough to dismiss events, Happenings, performances as theater rather than art. Certain formalists thought art should be pure: pure paint, for instance. No poetry, no confusing illusions or extra dimensions, no theater. And certainly no politics. It was a puritanical trope, as if there were no theater in a Pollock drip painting or a de Kooning parkway, no poetry in a Motherwell elegy.

Marina Abramovic's "Seven Easy Pieces" comprised seven performances staged at the Guggenheim (November 9-15), in evenings that went a long way toward the redemptive. With the exception of Matthew Barney's 2003 extravaganza (the films were better than the props), the Guggenheim has not exactly been pushing the envelope. We think of it more or less as a giant rental space for would-be crowd-pleasers. But now there's hope.

I first heard of Abramovic when she was Abramovic and Ulay, of Yugoslavia and Germany respectively. The couple stood naked in a small doorway and the audience had to squeeze through. Later, just before they broke up, each stated to walk from opposite ends of the Great Wall of China and met mid-point. Then too she was on the famous 1979 Crown Point Press trip to Ponope in Micronesia: John Cage, Laurie Anderson, Chris Burden, Pat Steir, yours truly, etc. But I don't think we exchanged more than two or three words, since I was more interested in wading into a lagoon full of sea cucumbers.

At the Guggenheim, Abramovic's test of will-power (hers and the audience's) offered not merely the usual Performance Art Challenge, but also the frisson of appropriationism, since five of the performances were recreations of work by other artists. The gold standard was represented by Joseph Beuys' 1965 How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare and Vito Acconci's 1972 Seedbed. In How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare, Beuys (a beloved art professor in real life) did just that, his face covered with gold leaf. In Seedbed, Acconci delivered a monologue while masturbating unseen under a false floor in a Soho gallery.

After prepublicity for the Guggenheim's Abramovic festival, San Francisco conceptual/performance artist pioneer Tom Marioni sent a letter to the New York Times to clarify shoot-myself, crucify-myself Chris Burden's refusal to allow Abramovic to replicate any of his performances. Marioni wrote: "The performance art of the early 1970s was concrete. We made one-time sculpture actions. If Mr. Burden's work were recreated by another artist, it would be turned into theater, one artist playing the role of another."

I agree. And, let it be known, I have nothing against theater per se, in any of its forms, as long as I don't have to sit there and watch it.

Some found Seedbed the most disturbing of all the pieces. But, remembering Acconci's original, I did not. Parents with infants in strollers waited on line to expose themselves and their offspring to a rambling spiel. A monologue is a monologue. Well, said a friend, a woman masturbating is not as threatening as a man. Why, I asked, is a man masturbating so threatening?

Just in time -- actually a few weeks later -- a woman friend told me at Thanksgiving dinner that near the Jefferson Market Library a man in a van had been blithely having a go at his gigantic member in full public view. She called the cops on her cell phone. But why, asked another guest (a man), he was just having a bit of fun or was feeling lonely. She shot back across the turkey leg and the mashed potatoes: Would you want your daughter to see that? I don't know, said her male partner. Exactly how big was he?

Abramovic also replicated one of her own performances, the 1975 Lips of Thomas, which I skipped because I do not like to see anyone cut herself (or himself) with a razor blade. The question here is whether or not in this piece she was pretending to be Abramovic.

Her great moment, however, was the last performance on the seven-evening course of events: Entering the Other Side, A Living Installation. Lifted to the level of the first ramp, inside a shiny-blue evening dress that fell over and concealed the multitask platform that had been used for the previous Performances, she reigned supreme. She was at the center of the Guggenheim, which is rather like, as you know, being at the center of a snail; and she deliberately, slowly eyed the worshipping crowd, arrayed below and on the ramps above. Now that was something to see.

Abramovic: Entering the Other Side, 2005.

* * *

In any case, Abramovic's "Seven Easy Pieces" certainly set me thinking about performance art again.

Performance art started in the late '60s.

Performance art, since it is ephemeral and unsaleable, was perfect for making an anti-commerce statement and was a kind of call to arms and/or affirmation of art's higher calling. Categories and genres? The hell with them. MFAs? No one thought them pertinent. Galleries? The devil's work, through and through.

Unfortunately, performance art could not pay the rent. This is why so many performance artists (like Beuys himself) depended upon and still depend upon academia or, as an alternative, living a living death as manufacturers of art products of one sort or another, trying to capitalize on former glory. Marina Abramovic is not one of these. She has remained loyal to the cause, and so Artopia honors her for that.

Vito Acconci, Following (Street Work), 1969.

Hidden History

I, a poet, artist and art critic, was a member of the street works and performance cadre in N.Y. City, 1967-69. The others were poet Vito Acconci (then the editor of a magazine called 0-9), writer/artist Eduardo Costa from Buenos Aires, writer Scott Burton, Pop artist Marjorie Strider, poet and underwear designer Hannah Weiner, and Acconci's sister-in-law, poet Bernadette Mayer. There were many others who participated in streetworks and performance art events: poets Anne Waldman and John Giorno come immediately to mind. At the final mass Street Work in 1969 there were up to 500 artists and poets involved on the streets of the new art district of Soho.

The cadre, which met weekly and sometimes daily, plotted the strategies and the venues, which ranged from designated streets during designated hours (my idea) to universities (Hunter College and N.Y.U.), the Whitney Museum and also, out of town, the Wadsworth Atheneum. The Center for Inter-American Relations and the Architectural League also sponsored some projects. Inspired by Earth Works, I invented the term street works. Marjorie Strider came up with performances and performance art. Scott Burton, whose bent was more theatrical, came up with theater works.

Acconci and I had already been offering what we called poetry events at venerable literary venues such as St. Marks Church. We shared the goal of getting poetry off the page. Strider, at one time married to Michael Kirby (who wrote the book on Happenings), had participated in some of Claes Oldenburg's Happenings in the '50s.

Happenings, however, had long been subsumed by object-making, in the case of all but the steadfast Alan Kaprow. What were Happenings? Kirby defined them as non-matrixed artists' theater, with Futurist and Dada precedents. How were performances different from Happenings? Or for that matter from Fluxus events, such as those of our hero Joseph Beuys' lecture to a hare?

From my point of view, performances were sculpture. When it became obvious to me that they were becoming theater (and not just sculpture in a theater context), I sealed my participation with Oedipus, A New Work, in 1970, which was -- ironically -- documented in The Tulane Drama Review. I was also uninterested in some of the sado-masochistic routines of some performances as they morphed into body art.

Performances, unlike Happenings, were always executed by the artist himself or herself, not by surrogates. When Scott Burton in the '70s began to use gaunt, often naked stand-ins to pose on his furniture, I thought he was entering a realm more influenced by Robert Wilson than Beuys. Performances were probably closer to Fluxus events than to Happenings, except that performances were time-and-space sculptures rather than task-driven koans. We eschewed the whimsical and the Zen.

Scott Burton: Untitled Bronze Chair (Street Work), 1972.

Whatever Happened to Performance Art?

After performance art'sconvulsive origins, that which did not become stand-up comedy became the loss-leader or the out-and-out freebie that advertised more saleable products. Back then, during the poetic genesis of performance art, we even called this the Oldenburg Effect. I doubt that Oldenburg planned it that way, but stage props from his Happenings became highly desirable sculptures. I know for a fact that furniture sculptor Burton was enamored of this strategy and lost no time moving from chairs as props to chairs as sculpture. In the world of Fluxus events, one could buy chalked up blackboards from Joseph Beuys "lectures." And once it became clear that masturbating under a specially constructed, ramplike gallery floor (Acconci) or having yourself shot in the arm (Burden) could make you famous, all sorts of lesser stunts proliferated throughout the '70s and into the '80s.

Now it is safe to say, notwithstanding all these fine points of nomenclature and classification, that artists schooled on Beuys, Acconci, Burden and Burton et alia offer up performances as sidelines, in the same way artists once made watercolors. Or use them as attention-getters, like sculptor who kicked off his career by videotaping himself shooting and killing a dog.

The art school rule is to start with an idea and then use the most suitable form, whether that form be video, performance, or even painting. And you are no longer just a painter; you are an artist, in order that one's work may embrace all media if necessary. The only problem is that, although there is no shortage of media, there is, as usual, a severe shortage of ideas. How many good ideas are there?

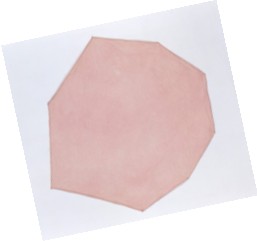

Richard Tuttle: Purple Octagonal, 1967

Richard Subtle

"To make something which looks like itself is the problem, the solution."

Richard Tuttle

The new Richard Tuttle retrospective, initiated by SFMOMA and now at the Whitney (945 Madison Avenue, to Feb. 5), opens old wounds. But a rehash of yesterday's art rages is instructive in outlining how hierarchies function, how blame is apportioned, and how custom impinges upon artistic innovation. Essays in the current catalogue gingerly brush against bristles once raised.

An extremely negative review in the New York Times concerning the first Richard Tuttle exhibition at the Whitney Museum in 1975 seems to have had a lot to do with (1) curator Marsha Tucker being asked to resign and (2) Tuttle's eventual fame. Tucker, whom I remember swearing she would never focus on aesthetics again, went on to found the New Museum. On a new DVD called Richard Tuttle: Never Not An Artist (dir: Chris Maybach for Twelve Films), Tucker claims her departure was the best thing that ever happened to her. It's doubtful that the Whitney would have produced "Bad Painting," "Bad Girls," and the first Ana Mendieta retrospective (with yours truly as co-curator), all New Museum exhibitions of some importance.

Please note that it was not the director who was forced out of the Whitney, nor was it the chairman of the exhibition committee, nor, heaven forbid, the chairman of the board of directors. Although the Tuttle exhibition in retrospect was a brilliant experiment, someone in the museum hierarchy was asleep at the wheel. Who was in charge? Or was it simply that Tucker had not prepared her bosses for the exhibition? Why did anyone worry about an attack in the New York Times, by Hilton Kramer? Nowadays an attack by him is as good as praise.

Or, as my old friend the dance critic Edwin Denby told me when I myself was attacked by Kramer, just measure the column inches. That's what counts. Every dancer knows this. Kramer had called me avuncular, which struck me as odd, since at the time I had hair like a lion's mane and was routinely called "Jesus" by truck-drivers. To make matters worse, Kramer had misspelled my name. Oh, the pity of it.

Tuttle went on to become an art hero, all in the name of beauty. Kramer eventually moved from The Times to the New York Observer, a venue more suitable to his bent and where, although still foaming at the mouth and whether one disagrees with him or not, he can do less damage.

Richard Tuttle: Purple Octagonal, 1967

Breaking the Rules

In regards to the 1975 Tuttle show, even Lawrence Alloway in The Nation went after the jugular -- Tucker's. What caused all the ruckus?

Believe it or not, for Alloway the problem was that there was no catalogue for the opening. He had no difficulty with Tuttle (after all, the artist's dealer was a close friend, about whom he had been commissioned to write a biography). Was there a Tucker vendetta of some sort?

The exhibition was to be changed by the artist three times during the course of its run, so a catalogue to document these events had to wait until the end. Tucker, who had co-curated the Whitney's "Anti-Illusion" show in 1969, was no stranger to site-specific, process art. And neither were we. For that show I remember that Rafael Ferrer dumped autumn leaves and blocks of ice on the Whitney entrance ramp. Robert Morris's Continuous Project to be Altered Daily also debuted that year in a warehouse rented by his dealer, Leo Castelli.

For Tuttle's 1975 retrospective, the artist himself had almost total say in the installation, but then again, many of the works required this and were about installation. General art-height was determined as an inch or so lower than art industry standards: 54", like light switches. But some tiny works were daringly placed where a baseboard might be. And some were on the wall, and then in the next installment spread out on the floor. Sometimes top-and-bottom orientation -- as in the signature, Tintex-soaked canvas "Octagons" -- had to be improvised. And his still delicately beautiful "Wire Pieces" needed to be made on the spot, as did a room of string-drawings laid out on the floor (not in current exhibition).

Installation was, and is, all-important to Tuttle. A big empty wall or a floor is the ground for his 3-D doodles, his hand-held, hand-made assemblages, his disconcerting, apparently off-hand sculpture/painting/drawings. He had, after all, started in the art world with a day job as the gallery assistant, backstage installation-guy at the prestigious Betty Parsons Gallery (where Jackson Pollock had shown and where Ad Reinhardt, Tony Smith, and Barnett Newman were then still in the stable). Tuttle's focus on presentation was inherited from or inspired by his gainful employment. It was there at Parsons that Tuttle had his first solo exhibition in 1965, which is a little bit like a Warner Brothers usher getting to fill in for the song-and-dance man on the mend and turning into Dick Powell.

What? Let the artist do his own museum installation? Dicey, at best. A post-exhibition catalogue? Still unusual now. We need those catalogue essays, no matter how badly written, to write our review or, as laypersons, misguide us through the exhibitions. Both "innovations" signaled a break-down in museum protocol - i.e., territory and control.

Richard Tuttle: Purple Octagonal, 1967

A Threat to the Art Supply Industry?

To make matters worse, a lot of the works were made of bits and pieces of what would normally be studio debris, little bits of nothing anchoring big expanses of formerly inarticulate, all-white museum wall space. String, wire, fluff. But didn't Kramer get the charm of these strategies, or at least understand the precedents? Had Kurt Schwitters lived in vain? Although even then Tuttle was understood in the art world as being -- albeit perhaps too mystical and too poetic -- an important part of what would be soon valorized as postminimalism, Mr. Kramer seemed to be obsessed with the reductiveness of Tuttle's scale, which to my mind was -- and still is -- heroic in its displacement of the bigger-is-always-better American cliché. Tiny does not necessarily mean twee. But I am still not sure we have learned that yet.

As it turns out, Tuttle, in spite of some bad press, went on making art and, as the current exhibition proves, most of it is quite good: loopy, tender, deceptively modest. At this point, his triumphant retrospective is the one museum exhibition in New York not to be missed. Delight without cheap sentiment is not easy to find.

Guess what. After 1975, the art world was not destroyed. Not all artists suddenly demanded to install their exhibitions -- some, in fact, understood they were better off leaving it to the experts. One of my fantasy student assignments has always been to require the installation of a group of art masterpieces so that they look really, really dreadful. The assignment is far too easy: wrong lighting, wrong spacing, wrong placing. Even inappropriate framing can ruin the best of paintings. It all hangs within an inch of disaster.

Furthermore, after latrines, sponges, dead hares, and little bits of cloth and bubble-wrap, we now allow dung, sharks in formaldehyde, gingerbread, and any number of post-Dadaist/Fluxus, postminimalist nonart materials. Nevertheless, the art-supply industry is as strong as ever. Tubes of oil paint and acrylic still outsell chocolate syrup (re: Vik Muniz currently at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia to Nov. 27) and toothpaste (murals by yours truly) as art materials.

Richard Tuttle: Purple Octagonal, 1967

Did He Really Say That?

Other Tuttle problems are less easily solved: his mysticism (since mysticism is still a no-no unless you are in Europe or California) and his tendency to offer gnomic statements.

Although his assertions that his work is an effort to overcome identity, and that "The job of the artist is to come up with ideas of how the mystic can be accommodated" might be puzzling to those not spiritually inclined, exhibition organizer Madeleine Grynsztejn also quotes him more productively in her excellent catalogue essay:

The main subject of my work is this kind of perfection, it's an experience I've had, it's a kind of metaphysical, or maybe someone else could say a 'mystical' experience that's happened, say, three times or four times in my life and I would like it to happen everyday and I would like to be able to make a picture or a sculpture where other people can have that experience because when you have that it also clears the mind.

All of this would sound less scary if recast as what once-trendy psychologist Abraham Maslow called "peak-experiences." Maslow in the '60s had the brilliant idea of studying healthy people for a change and found, he claimed, that they were all mystics, or at least had experiences of unity and transcendence that, to soften the blow, he called peak-experiences: Religions, Values and Peak-Experiences (1964) and Toward a Psychology of Being (1968).

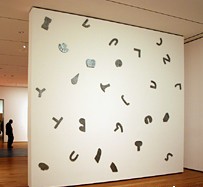

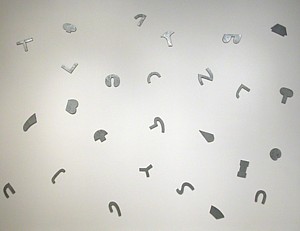

Aside from mysticism, is Tuttle's art (as Tucker seemed to have concluded) only about aesthetics? Even a stick or a wire tells a story. There is also the language-as-subject problem. To some degree, Tuttle has been producing alternate alphabets. Letters of 1966 is even composed of 26 discrete forms to produce a constellation of forms you can almost but not quite read. The same may be said for most of the Tuttle "runs," such as the "Octagons," the "Wire Drawings" and even the framed drawings of various sorts in a series or as exemplifications of theme-and-variations. Can all these "letters" be combined in different ways, as in scholar Moshe Idel's rediscovered ecstatic Kabbalah, to yield fresh meanings? Given five materials or five "letters," how many words can the permutations spell?

The alphabet has always been important to me. In the late '60s I did a number of performances structured by it; one, as it turns out, at the Whitney. Although as a child I could read before going to school, I had trouble memorizing the alphabet. It was, I felt, not my alphabet, not my language. Tuttle's alphabets are also not mine, but I can hear what they say. They say that Nothing - let's say a couple of inches of rope nailed to a wall - can be huge, that the ordinary can be sublime.

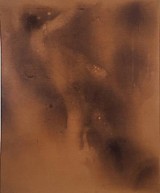

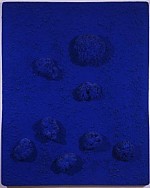

Yves Klein, Untitled Monochrome

Souvenirs of the Future

Georges Mathieu: What is artfor you?

Yves Klein: Art is health!

What is one to do with Yves Klein? A museum-quality painting survey at the L & M Arts Gallery ( "Yves Klein: A Career Survey;" 45 East 78th Street, to December 10) and seven late fire paintings made of torched cardboard at Michael Werner (4 East 77th Street, to December 23) move this wild man back into the spotlight -- at least here at Artopia, where we are busy forging a new canon, a new central strand in the spiral-braid of art history, a new future. Klein (1928-62) was the French Joseph Beuys, a statement that will be shocking to many, since Klein lacked Beuys' gravitas.

But who was ours? I say Barnett Newman. Duchamp evidently took a look at alchemy; Beuys nodded to esoteric Christianity. Klein embraced the Rosicrucian Conspiracy. And Newman knew the Kabbalah.

Klein's Monochromes now look great, but that's only because minimalism long ago caught up with his voids and outrageous concepts, going beyond his meanings. Klein was playing with the elements, and perhaps the elementals. His art, like Duchamp's, looks good because presentation is better than representation and because beauty is not the opposite of thought. It is, in fact, the highest form of subversion. He actually took a patent out on his particular saturated blue and deemed it International Klein Blue, applying it with rollers.

Klein, by all accounts, was a showman. He sold air, water, fire. As a young boy he imagined that he could sign the sky. He did sign the sky. He made paintings using the naked bodies of his female models, in public.

Yves Klein: Monotone Symphony Peformance, 1961

He composed (1949) and conducted (1960) The Monotone Symphony. To hear it go to: Ubuweb(click on MP3) He had himself pictured leaping out of a second-floor window. Did this publicity stunt stand in his way? No, on the other hand, that image of him jumping into the void made him immortal.

In hisChelsea Hotel Manifesto(click on same at bottom of opening page) he wrote: "Having rejected nothingness, I have discovered the void."

His only real handicap was that he was marketed as part of the so-called New Realism group, not that there is anything wrong with being associated with Arman (who has just passed away). New Realism could, however, be taken for French Pop Art and Klein, in spite of making p.r. one of his art materials, attained a level of profundity not attained by Pop, French or otherwise.

He too was an alchemist. Although outwardly it would seem that Dada and the aesthetic cannot mix, under certain saintly circumstances they do combine to form a mysterious third substance.

Americans were not ready -- neither for exhibitions at Leo Castelli and Iolas in New York and the Dwan in L.A., or later for his posthumous retrospective at the Guggenheim. The retrospective inspired the Times' John Canaday to announce that "the prodigious exaltation of non-sense is the really troubling thing about this exhibition." Whereas I myself thought it was Frank Lloyd Wright's building that was troubling, as a site for paintings; brackets that made Klein's sublime IKB's float in front of the curved wall were not exactly the right solution. Even with their curved corners they need good-old-Western rectangular walls.

The blue paintings look very different now: luscious. But in Klein's work, you should not avoid the void; art is not a question of content versus form, and/or form versus content, but one of parables and paradoxes, using the visual to conjure the invisible.

If nothing else, Klein is the postwar paradigm of the artist who does not limit artistic practice to painting or sculpture or performance, but exercises within all three. Or exorcizes all three.

Yves Klein: Untitled Fire Painting, 1961

Time's Purification

Klein achieved a Black Belt in Judo in 1952 (from the Kodokan Institute in Tokyo) and then went on to found his own Judo school in Paris, making a living teaching Judo from 1955 to 1959. As poet/artist who until quite recently had what actors call "a day job", I am always interested in how artists make a living. Joseph Beuys - another art hero - was for many years a professor at The Dusseldorf Academy of Art until he was dismissed for "breach of the peace" when he and his students protested the Academy's demand that he limit class enrollment. Marcel Duchamp worked at a library in Paris, later became Brancusi's U.S. agent, advised collectors and sold art privately, then married well.

Klein's Tokyo stint contributed to the notion bandied about that his monochromes were Zen-inspired, when in point of fact he had begun making monochromatic paintings well before his studies in Japan.

As the exquisite exhibition at the L & M Gallery may indicate, Klein's art has now undergone time's purification. Hardly anyone now would deny that the monochromes and the body paintings are beautiful. The spectacle has been removed. They are no longer performance art residue. The charlatan-like spiritual edge is subsumed by pure product.

Perhaps each decade gets the Klein it deserves. In the Sixties and Seventies we liked him because of, not in spite of, the faked image of him jumping from a building. And because of the Immaterial Transfers: he traded gold dust for particular chunks of space; the gold dust then dumped in the Seine. And then there was the legendary The Void exhibition: an empty gallery fronted by Republican Guards; the packed opening replete with blue cocktails. If the French art dealer Iris Clert is remembered at all it is for this one-week exhibit (and for Robert Rauschenberg's telegram to her stating: This is a portrait of Iris Clert if I say it is). Was the gallery empty? Not really. It had his aura. He had sensitized it by repainting it white.

But even the Anthrometries, made with paint-speared female nudes, are now almost painfully elegant. At first glance they have lost what once was construed in the late 70's as anti-woman exploitation. But they have also lost the touch of the Goddess.

We no longer seem to need to know that he was influenced by Rosicrucianism. Rosicrucianism, probably a joke, was a hoax that came true. Did Christian Rosencreutz actually exist? Was there in the 18th century really an elite of "invisibles"? Does it really matter, since the Rosicrucian manifestos enflamed the imagination and stood for liberty. Now ofcourse we scorn mail order "Rosicrucians" and celebrate the inspired scholarship of our beloved Frances Yates whose The Rosicrucian Enlightenment will provide some clues to the conspiracy.

Do we need to know that Klein was made a Knight of the Order of Archers of Saint Sebastian? Or, to be contrary, do we really need to know if such an order exists? Someone decked out in Archer regalia appeared at both the opening of The Void and Klein's wedding.

Yves Klein: Untitled Monochrome (with sponges)

Mutants Unite

But before Klein is belatedly initiated as one of the art immortals, can we undo Time's Purification? In re-reading critic Pierre Restany's book on his friend Klein, (Abrams, New York; revised 1982) I was reminded of that author's invention of New Realism (Arman, Tinguely, Cesar, Klein, etc). Has Klein, whom Restany called a "mutant", finally shed this cocoon?

Was Klein's seven years of truly inspired art production of the moment or of the momentum? Do we not still yearn for his architecture made out of air? Even if it was hot air? In 1962 he died of a heart attack after seeing the sensationalizing Yves Klein segment of the dreadful Mondo Cane at its Canne Film Festival debut. His last work was his one-way-into-the-void Pneumatic Rocket.

What I suggest is that we have an official Yves Klein Day. But this should not be the anniversary of his fatal heart-attack at the age of 34, but instead November 27 --- coming up soon! This is the date of his one-day newspaper, issued in 1960, disguised as the Sunday Edition of France Soir:

Here is Restany's description:

Under the headline "A Man in Space," and the caption "The Painter of Space casts Himself into the Void," a photograph, a mysterious photomontage, shows us Yves Klein hurling himself in soaring flight from the mansard roof of a suburban house. The black-and-white reproduction of a monochrome proposition is accompanies by the caption: "Space Itself."

And then there was Klein's editorial, as quoted by Restany:

I have decided to present an ultimate form of collective theater, a Sunday for everybody...By presenting Sunday 27, 1960 from midnight to midnight, I thus present a holiday, a genuine spectacle of the Void.

All of this is in Restany's book on Klein which also documents an artist/critic relationship. Restany, along with inventing French New Realism, apparently got Klein to focus on the color blue and to insist that his paintings had nothing to do with Malevich. And how did Klein pay him back? When he was mentally formulating the faculty for his projected School of Sensitivity, his artist friend Tinguely was to be in charge of sculpture, but Pierre was in charge of press.

In truth there needs to be a dialectic between essence and context. But are the paintings the essence? I'd vote instead for the photomontage leap.

So how will you celebrate Yves Klein Day this November 27? Paint yourself blue? That's now too Blue Man Group. Jump from a second story window? Two dangerous. How about gazing into the sky while reciting "I AM the Void"?

Yves Klein: Leap Into the Void, 1960

For e-mail Artopia Alerts of new entries contact perreault@aol.com.

AJ Ads

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

innovations and impediments in not-for-profit arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

Joe Horowitz on music

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary

Tyler Green's modern & contemporary art blog