John Perreault by John Perreault, 2010, dimensions variable. (Image of Portrait of John Perreault by Philip Pealstein,1973, multiplied and altered with Pop Art app and Picnik).

“There are no second acts in American lives.”

— F. Scott Fitzgerald.

Drella by Starlight

“Andy Warhol: The Last Decade,” at the Brooklyn Museum through Sept. 12, is essential but problematic. Originating at the Milwaukee Museum of Art, it is a thin survey of the Pop Pope’s second act. The art world has already seen these images before, here and there, and repackaged at various Gagosian galleries. Not entirely pleased by the selection, I scrambled through my Andrew Warhola library to locate entire series not included — some justifiably so, some mysteriously omitted.

Death is not the ultimate curator; it merely sets the stage. But it does offer some career advantages. No further false starts, missteps and, after a point, no undiscovered work. The sorting can begin in earnest. Death imparts a certain stability.

The thesis is that Warhol (1928-1987), through a new interest in abstraction, judicious recapitulation, collaboration with younger artists and a return to hand-painting, achieved new glory from 1977 to his death in 1987. Well, yes and no.

The 1979 Whitney exhibition “Andy Warhol: Portraits of the 70s” was loathed, even by yours truly. Celebrities were interchangeable. Anyone able to cough up the bucks could be as famous as Marilyn or Liz, as if a mediocre silkscreen painting could really confer fame. Andy had not been inspired. Even portraits of people he apparently knew and liked, such as Metropolitan Museum curator Henry Geldzahler (who gave him the idea for the winning Disaster Series) or charming superstars like Liza Minnelli, turned out vapid, almost as if he had intended it. Only Andy’s grand and perverse paintings of Chairman Mao were deservedly well-received.

Two years after Andy’s death, the 1989 MoMA ritual retrospective put the nail in Drella’s coffin. Drella? His Factory nickname tellingly combined Cinderella and Dracula. The Valerie Solanas assassination attempt was the great divide. Even those who originally hated the soup cans and Marilyns suddenly discovered how truly great Warhol had been before those nearly fatal shots to the chest in 1968. Nevertheless, Robert Hughes in Time magazine reported how distraught the operatives of the Warhol estate were that so few of the 273 works at MoMA were post-assassination. But hadn’t Andy already given up painting with his Castelli show of cow wallpaper and silver pillows? We now know that along with founding Interview “fanzine” (with poet Gerard Malanga), forays into cable TV, producing Paul Morrissey’s films, night-clubbing, sucking up to celebrities and debutants, public appearances and product endorsements, Andy soon came up to speed after the shooting and was no slouch when it came to the main game — paintings. Luckily for fans, he left behind a mountain of investment opportunities.

At first his methods did not change. He fished for painting ideas or continued to accept commissions, selected and cropped the images, then supervised the silk-screening. The most important moment was signing the results. The flaw was that after collaborating with the likes of new art-star Jean-Michel Basquiat, he decided to go back to “hand-painting,” appending a surprising callowness to his Retrospectives series by trying to duplicate the spirit behind his first — and hand-painted — efforts at Pop.

Warhol never had a hand worth thinking about, and his art can in part be explained by his efforts to work around that fact. In his illustrations, he sometimes used his mother’s hand and/or a blotted line. Not everyone can be de Kooning or, in a more studied manner, Jasper Johns; or in an unstudied one, Robert Rauschenberg. These examples notwithstanding, a good hand does not automatically mean great art. That would be too simple. Many an artist with a great hand has produced trivial art. It is, however, something you cannot fake.

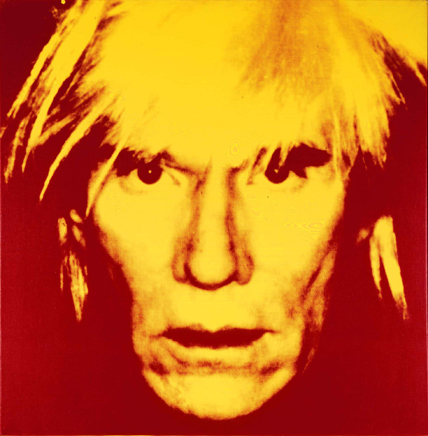

Andy Warhol, Self-Portrait, 1986. Acrylic and silkscreen ink on linen, 40 x 40 in. (101.6 x 101.6 cm). Mugrabi Collection. © 2010 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./Artists Rights Society

Fame Queens I Have Known

An archaic term, dating from the ’50s or earlier, Fame Queen (linguistically related to other specialty categories like Leather Queen, Dish Queen, Size Queen) was used in gay patois to describe someone inordinately fond of famous people — who seeks them out and in some sense collects them. Usually, but not always, “a friend of Judy” (i.e., gay), the Fame Queen worshipped at the altar of Garbo, Garland, Liz, and Liza. There were subcategories too, Opera Queens being the most notorious and most annoying, dating back to at least the 18th century.

Compared to Fame Queens, sports fans are wimps. Fame Queens pushed the envelope of irrational adulation. Autographs and “sightings” were only the beginning. The latter sometimes developed into stalking. In the higher echelons, Fame Queens populated their dinner parties and sprinkled their cocktail events with the famous and the infamous: actors, models, politicians, designers, mass murderers and even artists. The auras rubbed off on the host. You could become famous for knowing the famous. All you had to do was get your picture on Page Six a sufficient number of times.

As a Fame Queen himself, Andy knew that everyone wanted to be famous. Fame makes you sexually attractive. So he conferred his legendary 15 minutes of fame upon almost anyone who would apply. Fame rubbed off on you. You could catch it like a tropical disease. Or aura.

Even if you were beautiful — which Warhol was not — you had to have a hairdo or a look; you had to make yourself photogenic and instantly recognizable; you had to know how to make an entrance; you had to know how to deliver quotable lines that could turn into headlines. Andy also knew, alas, that fame had no morals. In the Warholian universe, tyrants and creeps were equal to the most liberal of movie stars. He was wrong about most debutants, about all art collectors. He was wrong about industrialists. He was wrong about the Shah of Iran and the Shah’s wife.

By studying art fame, Andy learned the ropes. When he wasn’t at his table with his protective entourage of Factory Superstars in the backroom of Max’s Kansas City or at an opening or at a party, he was on the phone pumping art critics: David Bourdon, Gregory Battcock, even myself, recording every word, wanting to know what everyone was doing and who was where. Gossip was his drug of choice.

The art books began to appear. The museum exhibitions proliferated. And so did all the product lines: prints, then posters, placemats, shopping bags, and souvenirs. By putting the shopping cart before the horse, his premature release of art peripherals made him look like a master before the fact.

Or was he being ironic?

Irony allows you to have everything both ways. You can become famous by making fun of fame. You can laugh all the way to the bank by making fun of art-as-business. Parody can pay.

The horrible joke is that by revealing the business side of art, developed in the U.S. in stealth during the pre-Pop art period, Andy – smart but fey Andy — made business the norm, thus inspiring some very talented successors, specifically Jeff Koons and Damien Hirst who seem to glory in the tongue-in-cheek transparency of art-as-business. Parody risks becoming paradigm. And art-as-publicity? Salvador Dalí was first. Or perhaps Tristan Tzara.

Andy elected to fess up, to let the cat out of the shopping bag. Fame, even in the art world, could be faked. That was why certain powerful critics hated his guts. And some well-established artists, too. But by admitting the tricks of the trade, he transcended the dark side of art. Worse yet, he blew up the Romantic ideal. The artist is not autonomous. Ideas? Many were suggested, some were selected.

Andy knew all about Dada. His first New York roommate was his Carnegie Tech classmate Philip Pearlstein, who did an early, painterly painting of Superman, later became a respected realist painter of nudes, and who wrote his MFA thesis on Francis Picabia. Andy also knew all about survival.

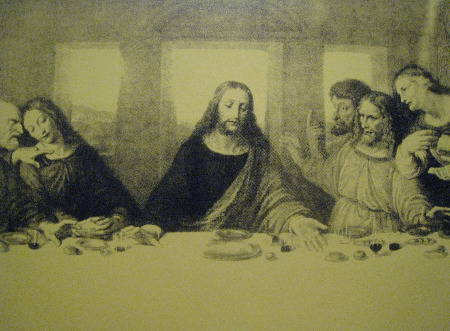

Warhol, Last Supper © 2010 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./Artists Rights Society

What Price Fame?

Coming from commercial art — where he was already an established illustrator — Andy had no heroics. His playful illustrations bought him his townhouse. He financed the early years of his Pop art career by continuing his commercial art ventures. One form of commercial art supported another kind of commercial art.

In commercial art proper, everyone had a voice in how a layout was finalized, an image locked down, a sales-point sealed. Signatures had no authorial weight. As a fine artist, Warhol became the art director of his very own brand.

Which works are best? The artist is the last to decide. Critical reception? Well, not even that, since the market selects most favorites, by default. And that is not entirely a bad thing: some artist don’t have a clue. They are not necessarily the best critics of their own work; distance is not possible. Critics are myopic; so let’s leave the final cut to the market.

But when was the last time you read someone attack a ridiculous auction price or a collector’s purchase? Private collections, no matter how quixotic, gross or conformist, are always beyond criticism. Collectors buying and selling like blue-chip art dealers, stacking the cards, and inflating prices for gain are left to play their games. No one wants to look a gift horse in the mouth.

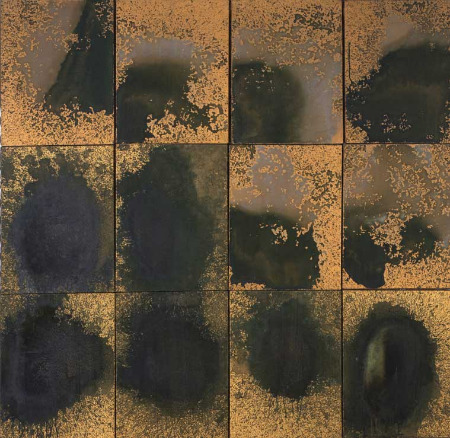

Warhol, Oxidation Painting. . © 2010 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./Artists Rights Society

Warhol Tip Sheet

And here at last is what you have been waiting for:

Kinds of paintings represented in the current exhibition, but should have been omitted:

1. Apparently first conceived as Easter presents, the “Egg Paintings” are banal in an uninteresting way. The banal, paradoxically, can be “interesting.” A popsicle stick, a tongue from a sneaker, a thermometer in a birdcage, if looked at in the right way, can be metaphysical. But not flat, solid-color egg shapes in random display. They do not even work as decoration.

2. The yarn paintings were commissioned by Filpucci, an Italian yarn company, and it shows. The visual reference to Pollock’s drip paintings is not all that clever, is it? And take that away and you have a big yawn — a yarn yawn — or possibly a good pattern for wrapping paper. Well, why not? Warhol did produce cow wallpaper. I think there is a marketing potential here. Yarn-painting fabrics would work, too. I’d like a cowboy shirt made of that.

3. The collaborations with Jean-Michel Basquiat are neither Basquiat enough nor Warhol enough to matter. I may be in the minority, but Basquiat’s charms (aside from his good looks) have always escaped me. His work may be graffiti-based, but it is also a secondhand look at cubism and Stuart Davis, a look we don’t necessarily require.

But here is something to ponder: It is very interesting indeed that Warhol embarked on some collaborations with Basquiat and a few other fashionable artists younger than himself. No doubt this escapade and his desperate need to keep up with shifts in art-world taste influenced him. How do you represent this in an exhibition without also signaling approval? If you label the work as lacking, the loan will most likely be withdrawn or at the very least the source will forever be closed to you. Solution? Picture (if possible) or at least mention the work in the catalog — where such things really count — but keep it off the walls.

4. I know the prestigious Dia Art Foundation once offered up an entire show of the Shadow Paintings. One of its biggest mistakes. What is this image a shadow of? Because you cannot tell, the series is just a suite of boring variations, some sprinkled with diamond dust. Yes, I hasten to add, boredom like banality can be very, very interesting. But, alas, not in this case.

5. I am not sure I can be objective about the Camouflage Series, because I myself produced some paintings of camouflage and studied it for awhile, way before Warhol. Archille Arshile Gorky painted real camouflage during World War II, and the name of my first book of poems is — guess what? — Camouflage (1965). Even when Warhol applies camouflage to his fright-wig self-portrait, it seems routine.

6. Missing in action, but not at all missed, are the skulls, the crosses, and the hammer-and-sickle paintings. And the portraits of famous Jews (I am not kidding) are nowhere to be seen. Add the de Chiricos, funny now only if you know that Warhol chose images of the late paintings that Giorgio de Chirico himself copied from his now classic “metaphysical” period. No one wanted his pseudo-Renoirs.

Warhol: Rorschack Painting. © 2010 Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./Artists Rights Society

And the winners are:

1. The Oxidation Paintings are sometimes called (maybe too accurately) the “Piss Paintings.” Male and female volunteers urinated on surfaces of copper paint causing landscapes and cloudscapes of oxidation. Shower queens will rejoice and others will be simultaneously attracted and repulsed. What could be better? These are far better as parodies of and statements about Abstract Expressionism than are the dismal Yarn Paintings.

2. The Rorschach Paintings. To make one, pour and fold. Anyone can do it. Sort of. The two Rorschach works here, like the Yarn and Oxidation paintings, refer to AE. These Rorschach splots, inspired by the well-known psychological test, are more gateways to the conceptual than to the subconscious. Perfect gifts for super-wealthy shrinks with big, big lobbies. Or Bellevue Hospital?

3, The Retrospectives. Negative versions of the Warhol classics, only bigger and clearly destined for museums that can handle the scale… and the mournful tonalities. I was surprised. Copies of pictures of copies. Like the fake de Chiricos by de Chirico.

4. The Last Supper Series was commissioned by a commercial art gallery across the street from the site of the actual Leonardo Last Supper. Here too, the biggest are the best. All of them are jokes about art-about-art and art as religion, rather than — as sentimentalists like to think – indications of Warhol’s personal religious convictions. Here, I don’t think the commercial commission ruined the results.

Silence Is Golden

At parties, imitating the master, the Factory entourage mostly sat on the sidelines in silence; thereby, no mistakes could be made. Silence — whether assumed by Garbo, Susan Sontag or Andy — always appears sagacious. The things you don’t say have more power than what you might blurt out. My favorite Warhol self-portrait image is not the fright-wig silliness, but the finger-to-the-lips image from the ’60s, connected in my mind to Redon’s Silence.

Well, Andy has now been silenced for years. Silenced for good. But can we see the art divorced from the hijinks, the put-ons, the camp? Better yet, should we? Now the camera can pull back for a greater view than the closeups could ever create, no matter how skillfully edited in a rags-to-riches montage — ending up in … Catholicism!

What is the Warhol legacy? Artistic talent can be executive as well as lone-wolf. The artist as CEO of his own atelier is more traditional than the lone-wolf valorized by Romanticism and perpetuated by Modernism. Unless an artist is born rich or marries rich, artists have to be just as practical as everybody else. Starving is not fun. But if the whole enterprise is only about making money, than the purpose of art is defeated. Parody becomes paradigm.

Never Too Late

Monet got better and better. Late Matisse is better than early Matisse. Late de Kooning is great. I find the “clamdiggers” and even his subsequent works, his hand freed up by aging, just fine. Duchamp’s “unfinished,” posthumous Étant donné is, in its own way, as mysterious as The Bride Stripped Bare by Bachelors, Even.

What can you do when you have achieved something rich and strange? Should you just keep doing the same thing over and over again?

If you are Duchamp you can pretend you have given up art.

If you are as visually loquacious as Picasso, you can (1.) play out all the variations of the discoveries you made as a youngster and/or (2.) climb on every bandwagon and trust that your own personality will prevail.

If you are Salvador Dalí, you can issue watered-down versions of your First Act success.

If you are Jackson Pollock, you can get drunk and drive to your doom.

If you are Andy Warhol, you can die and……..be born again.

Warhol: Last Supper (detail).

FOR AN AUTOMATIC ARTOPIA ALERT CONTACT: perreault@aol.com

John Perreault is on Facebook.

You can also follow JohnPerreault on Twitter.