The Plot

Site-specific art has subjects. Content needs to be parsed. In the best examples, the artworks initiate a kind of dialogue between place and viewers, illuminating where we are. Dreary forms of personal expression are at least once removed. Furthermore, it gets art out of galleries, museums and penthouses.

What I have never said before is that site-specific art harkens back to a time before easel paintings and the tchotchkas and mementos that now pretend to be sculpture. Unlike murals and monuments, however, the site-specific artworks of our times are usually temporary, so artists are free to experiment and take risks; here today, gone tomorrow. Does this then make such artworks a subset of theater? Well, if so, who cares? Artopia does not celebrate categorical purity; if anything, we enjoy and encourage the reverse. Or, as Walt Whitman once wrote: “Unscrew the locks from the doors!/Unscrew the doors themselves from their jambs!”

Not all of the works in Creative Times’ “PLOT/09: This World & Nearer Ones” are site-specific, although the best ones are. All of them, however, are what the curator, ex-Londoner Mark Beasley, calls “site-sensitive,” thus giving himself and the artists a bit more leeway. Perhaps.

Much more of the Artopian point of view will be revealed as I go through the various artworks that make up “This World,” now spread over the 172 acres of mysterious Governors Island in New York Harbor. I say “mysterious” because New Yorkers have seen the island from a distance, but most of us have never visited — unless we were stationed there during one war or another. Sold back to New York State by the federal government for one dollar in 2003, it is now ours to enjoy, at least on Fridays, Saturdays and Sundays (until Oct. 11). The boat that leaves every hour on the hour (but check here because “schedule will vary”) from the Battery Maritime Building to the left of the Staten Island Ferry Terminal is unequivocally, absolutely, mysteriously free.

But I also use “mysterious” because even curator Beasley proposes in his preface to A Guide to This World/ Nearer Ones that a number of his invited artists came up with works of a decidedly supernatural cast because they staked out their sites in the gloomy winter.

Of course, the old buildings left behind by the various military and government operations stationed on the island are bound to be haunted by history and long-gone events. Old structures are like that. Even in the harsh sunlight of July, there is something creepy about this island. We do not associate military sites with peace and joy, do we? Beyond the vale, dead soldiers linger.

Located between Brooklyn and Manhattan at the mouth of the East River, Governors Island is the perfect site for preventing any invasion launched from Jersey City or Bayonne, on the other side of the Statue of Liberty.

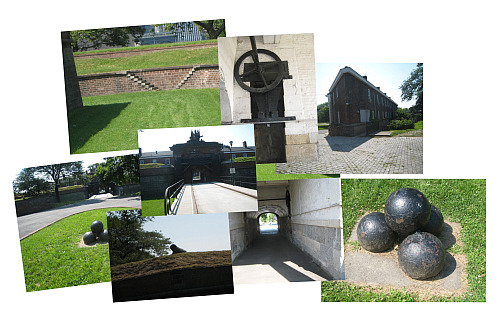

At the tip is Castle Williams, fortress then barracks then military prison, built between 1807 and 1811; its curved stone wall is visible from Lower Manhattan. Star-shaped Fort Jay at the island’s highest point dates to 1776. It was thought to be impenetrable and even has a moat.

Now there are lawns galore. No cars. Bikes can be rented and picnicking is allowed. And there’s art.

More interesting than the two forts — although you can’t beat an old fort for little-boy fun — are the ordinary buildings, many of which have not been open to the public: the Officers’ Houses along Nolan Park and on Colonels’ Row, and a movie theater forgotten by time, as they used to say, that time being what, 1965? To enter the movie house, you have to sign a release, because who knows what lurks behind those moldy wall-coverings. The same is true for the much less interesting Liggett Hall gym.

Maps and What They Allow

Two artworks are visible even before you hit Mystery Island. I found Mark Wallinger’s piece less than audience-friendly: One side of the ferry is labeled GOATS and the other SHEEP. Who is separating the sheep from the goats? Which group do you, dear visitor, belong to?

Pulling out from the slip, one may also notice Lawrence Weiner’s work on the wooden fender-rack: AT THE SAME MOMENT in red-enamel letters. The relationship of this phrase to Governors Island, to the ferry, and/or to the fender rack is elusive. It could be placed anywhere and still have the same meanings.

There is a third artwork that involves the ferry and the passage across the waters, but I will save that till last because I did not find out about it until I was heading home.

Special bright blue flags designate “This World” sites on the island itself, but the artworks are so spread out — as they should be if one of the goals is to give art-worlders a taste of Mystery Island — that a map is really necessary. However, finding the Creative Times visitor center, which is House No. 20 in Nolan Park. requires asking a guide stationed at the top of the hill from the dock.

Why, I asked, are there no art maps available when you first arrive? The Parks Department does not allow the distribution of handbills or any single sheets of paper, was the answer. The only solution is to buy the $5 A Guide to This World/Nearer Ones at the hard-to-find center; it’s mysteriously not available at the book and gift shop right off the ferry landing. You need a map to find the maps.

There are two maps you can look at online before you go. One from Governors Island does not indicate the art sites. The other is a Google map from Creative Time with signature pushpins. These when clicked give you art descriptions. If you click on the satellite view, you will get a good idea of the lay of the land, but that is of little use when you are on the island at ground level.

Furthermore, the maps in the Guide are not as clear as they should be. The numbering is curiously erratic. Thank goodness for the volunteers stationed at each art site. They were all very helpful at pointing out the direction I should take for whatever numbered site I pointed to in my Guide. Next time when Creative Time returns with what promises to be an important quadrennial, I am sure the mapping will be better. But this year perhaps there could be a trail of breadcrumbs from site to site.

Just kidding.

Also note that you should be prepared for quite a hike. You can rent a bike near the dock — on Fridays bikes are free. My investigation on foot, including watching several films, took about four hours! This is nothing like a museum survey that you can breeze through in under an hour.

At House No. 20 you can also gain the temporary use of an iPod-like device containing a Patti Smith “tour” with piano music by her daughter, Jesse. It’s free, but they hold your i.d. captive until the device is returned. This not a real audio tour. Instead, alas, it’s a sentimental text called Message in a Bottle, and it neither illuminates nor amuses. Smith was more poetic when she hung out with Robert Mapplethorpe and was everyone’s favorite punk star. Have a listen on the porch — it’s only 20 minutes, but one of the longest 20 minutes I have ever experienced — and then return it as soon as you can.

Noted on my way to the Info Center but not seen close-up was Teresa Margolles’ Shot-Up Wall, lifted cinderblock by cinderblock from the site of an organized-crime shooting in Mexico. Reconstructed, the wall is placed in the middle of Nolan Park and is pocked by bullet holes and flecked with what could be dried blood. I suppose it is a kind of anti-monument, the negative of heroic statues that might be found in a park, except that it is a markedly different kind of war that is being commemorated.

Margolles sounds like an interesting artist indeed. The Guide informs us she is one of the founders of the Mexico City collective called Forensic Medical Service (SEMEFO is the Spanish acronym). The group “uses cadavers, the clothing of the deceased, and morgue paraphernalia in works spanning from videos to public interventions.” A 2003 work of her own called Papeles (Papers) involved creating portraits of the dead by “letting watercolor paper absorb blood and other organic fluids left behind.”

Near by, in House No. 15, is Judi Wertheim’s double video called La Tierra de los Libres/Land of the Free. Wertheim gave a Spanish translation of the U.S. national anthem to a group of dispossessed Columbian farmers trying to make a living as musicians and asked them to sing the lyrics with their own improvised music. Because the site is close to Ellis Island, the U.S. port of entry, the project makes sense here. What’s really clever is that when you enter the bare living room of the house, you see a straight-on video projection of the group performing and then, when you circle the screen, you see another projection of them performing from the rear, with captions in English.

I next saw Anthony McCall’s fog and light-beam moving sculpture called Between You and I in the pitch black Saint Cornelius Chapel. It was elegant but, on the whole, I am not fond of walking blindly into an unknown space. I would have rather seen the Chapel.

In another dark room, the assembly hall of the Officers’ Club, I was able to see my way to the single bench available to watch Adam Chodzko’s 13-minute video Echo. As sort of a cross between The Blair Witch Project and The 13th Victim (plus Joseph Cornell’s home movies), the fiction (?) here is that military brats once had a game of “loser wins.” In other words, the winner would be whoever gave away the most valuable things for something of hardly any value at all. In 1624, the Dutch Governor of New Netherlands traded “two axe heads, a string of beads, and a few nail heads” with Native American owners Cakapeteyno and Pehiwas for all of Noten Eylant (Governors Island). And of course you can’t help but think of the 2003 deal between the feds and N.Y. State, right?

A further fiction is that the archive of the “game” has recently been discovered.

Found footage and ominous music make the whole thing work.

I had 10 minutes to kill before the next showing of The Bruce High Quality Foundation’s Isle of the Dead in the Fort Jay Theater. So I scooted ahead to take a look at Tue Greenfort’s Project for the New American Century in the Brick Village, formerly Coast Guard housing. Following a path through the site demarcated by chain-link fencing, one sees the oppressive housing, derelict playground equipment, and other poignant debris.

Time for the Isle of the Dead screening. “Is this the zombie movie?” I ask. “Yes,” says the volunteer.

There are only four of us in the audience. Why so few?

“Well, you know, ordinary people are afraid of art,” one out-of-town visitor volunteers before the movie starts.

“Afraid of art? This is New York City,” I answer. “People are afraid of their neighbors, not art.”

The 19-minute film by the Brooklyn-based Bruce High Quality Foundation collective is terrific. We see the art world die at various locations: MoMA, Chelsea, the Whitney. Serious-looking people are dropping dead everywhere. The corpses are intercut with montage sequences of found material showing JFK, the Art Workers Coalition, The Guerrilla Girls, and much, much more. The steps of the Met are strewn with corpses. And then….

Spoiler ahead!

Guess what? The cast of hundreds, most of whom look like art students, comes back to “life” and begins to walk like zombies toward Governors Island, then on Governors Island, then they are sitting in the Fort Jay Movie Theater watching the same movie you are watching. The art world made up of zombies has now moved to Governors Island. When I leave the musty theater and reenter the blinding, leafy daylight, I affect a zombie gait.

The volunteers, who seem not to have seen the film, don’t really notice. Or at least they don’t let on. That is how real zombies behave; they’re cool. And, in the video, they wear a lot of black eye-shadow.

As fate would have it, across the lawn, Klaus Weber’s gigantic wind chime was tuned to the devil’s tritone: “the mysterious diabolus in musica tritone, a musical interval that spans three whole tones, to dissonant and melancholic effect.” See here (rather, hear here) Giuseppe Tartini’s Devil’s Trill Sonatas, one of my favorites. The tones indeed are kind of a downer, but the happy picnickers stationed below seem not to mind. Was this tree a hanging tree? Was the field a potter’s field?

Then on to another haunting: Edgar Arceneux’s Sound Cannon Double Projection, in Building 404A on Colonels’ Row. We get to explore an empty house. But there are eerie sounds, mostly on the second floor. I hear a low rumble. The Guide reveals: “Researcher have suggested that infrasound … might be present in certain allegedly haunted locations, and cause a feeling of uneasiness. Infrasound can induce bizarre feelings such as anxiety, extreme sorrow, paranoia, or even the chills.”

Two houses down in 406A was the documentation for one of my favorite pieces: Insular Act by the Mexico City collective Tercerunquinto. One member, after much calculation and negotiation, threw a rock at a window in an historic building across the way, breaking the glass. The glass was immediately replaced. Again the question: why are certain building preserved and other not?

Readers may wish to know that having been the Visual Arts Director of Snug Harbor Cultural Center in Staten Island, I have a particular interest in historic preservation. My office had been Thomas Melville’s office when he was president of Snug Harbor, founded in 1821 to house “ancient, decrepit and worn-out sailors.” When Herman Melville’s ghost came to visit his brother Thomas’ ghost, as Herman had visited Thomas in real life, I would see them both out of the corner of my eye while I was filling out loan forms and grant applications, which must have been a puzzle to them. Furthermore, I am now trying to save an old lodge in Brookhaven Hamlet on Long Island. The house, which has 14 bedrooms, was once the summer home of one G., or George, Washington, the inventor of instant coffee. We want to turn it into a cultural center … with a coffee bar, of course.

More ghosts: In 407A we can peek through what could be glory holes and see the remains of Invocation of the Queer Spirits (Governors Island) by Canadians AABronson (formerly of General Idea) and Peter Hobbs: candles, flowers, empty bottles, dirty dishes. Hmm. No doubt Native American medicine men displaced by the Dutch gay soldiers and sailors once stationed on the island, and certainly the ghosts of all those shamanistic closeted members of the Coast Guards, came to visit during the séance.

More ghosts: In 407A we can peek through what could be glory holes and see the remains of Invocation of the Queer Spirits (Governors Island) by Canadians AABronson (formerly of General Idea) and Peter Hobbs: candles, flowers, empty bottles, dirty dishes. Hmm. No doubt Native American medicine men displaced by the Dutch gay soldiers and sailors once stationed on the island, and certainly the ghosts of all those shamanistic closeted members of the Coast Guards, came to visit during the séance.

Back across the way, however, Guido van der Werve’s two interminable videos, I don’t want to get involved in this; I don’t want to be part of this; talk me out of it and The clouds are more beautiful, are not even site-sensitive, never mind site-specific. They would bore viewers anywhere, although some might thrill at the artist falling from the sky after playing Chopin in one and failing to get a rocket to work in the other, the humor of which escapes me.

Then I hiked to Nils Norman’s tent city called Temporary Permanent Monument to the Occupation of Pseudo Public Space.

For good luck and to chase away the evil spirits, it was time for one of my interventions. I twice circumambulated the nearby Castle Williams and did a single spin inside.

.

Still had three more artworks to go.

I should have checked out Tris Vonna-Michell’s No Deviation Possible: Folded in That Precise Triangular Fashion at the beginning of my tour, if for no other reason than to get inside Pershing Hall. Alas, in spite of the blue flag, it was locked up tight, and I then found out No Deviation had been a lecture-like performance that left no residue.

Exhausted, on to Krzysztof Wodieczko’s Veterans’ Flame, a video projection of a single candle, accompanied by taped interviews with veterans, deep in one of the Fort Jay “magazines” where ammunition was once stored. Fort Jay definitely needs to be circumambulated.

I missed Susan Philipsz’ sound piece called By My Side, all the way at the end of the island. Will have to hear it some other time, since I was counting on a 5:30 ferry, the last back to Manhattan. This is what all the signs proclaimed. However, I noticed a huge line at the dock. It seemed that the last ferry for visitors was actually 4:30. The 5:30 trip was for staff only! It was four o’clock, but it would have taken me 40 minutes back and forth to Philipsz’ piece.

Off the Map

And then, last but not least, as promised, another artwork inspired by the ferry. Jill Magid — not Maggid, which means a Kaballah spirit guide. Magid prides herself on collaborations with nonartists (having shadowed a New York cop on his rounds and once been hired by the Dutch Secret Service to interview personnel to “humanize” them), began her project by talking with the Governors Island ferry captain, who wished he could make passengers aware of “the peaceful intrigue of the space between the islands.” Magid’s artwork, which you can discover, as I did, by carefully reading The Guide, was developed from this conversation. The idea became to stop the ferry at midpoint to allow the passengers to contemplate the unassisted movement of the boat on the waves, which of course could not be done. Instead, we are to imagine such a halt.

Ghostbusters

So why this spook show on Mystery Island? I think it is much more than the buildings that generated these hauntings. Other factors to consider might be the death of the art world, the death of the economy, the death of poetry, the death of the novel, and all the other endings that have been proliferating. Everyone has a favorite funeral to attend: print journalism, serious cinema, higher education, broadcast television, cheap energy, rock-n-roll, avant-garde music, jazz. For though we have long passed the turn or the century, we are at a turning point. It is at periods of great change that people, even artists, turn to the supernatural. Continuing to channel Marcel Duchamp and Andy Warhol may no longer be enough.

FOR AN AUTOMATIC ARTOPIA ALERT, E-MAIL: PERREAULT@AOL.COM