Tehching Hsieh has created only six artworks or, more precisely, performed them. This is not counting his earlier jump from a window in Taiwan or, before that, the paintings he made. The six artworks are the ones he lists on his website and that have been validated as art and valued as such.

* * *

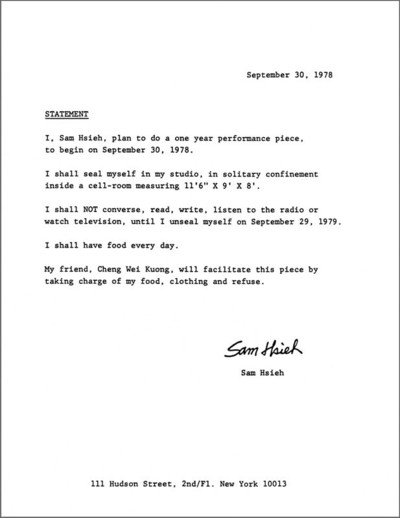

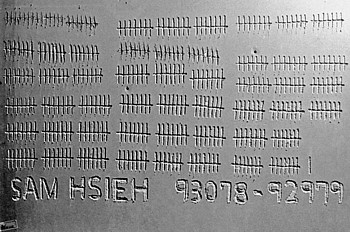

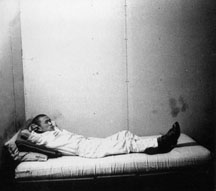

1. One Year Performance 1978-1979 — Hsieh lived in a locked cage without reading, writing, or talking to anyone, which is now fully documented at the Museum of Modern Art through May 18. What we focus on at MoMA is a wooden cage that includes, according to the wall label: “bed, mattress, pillow, blanket, sink, can, mirror, sheetrock walls, toilet paper roll, paper towel roll, toothbrush, bar of soup, nail clippers, glass cup, glass bottle, marked footprint, uniform, shoes, light bulb, tea bags, sponge.” Outside the cage, a lineup of photographs charts hair growth from shaven head to mangy mop. There’s a typed statement, sample handbills, and more photos, in themselves undistinguished, just doing their business as proof. You should also know the artist sometimes called himself Sam Hsieh.

At MoMA, it is illuminating to see the “sacred” residue of Hsieh’s first One Year Performance. Although we would have preferred a full survey of all six artworks, Artopia salutes the occasion. Since the current manifestation is not a retrospective, we hereby offer brief summaries of Hsieh’s complete oeuvre.

* * *

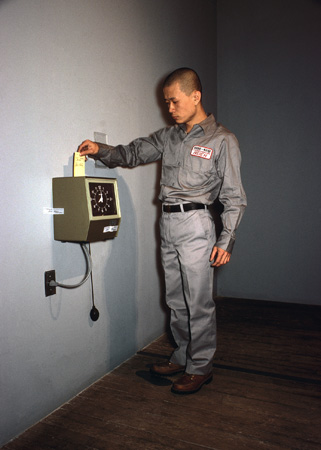

2. One Year Performance 1980-1981 — Hsieh punched a time clock every hour on the hour. Can you know about this piece without thinking of drudgery?Bank executives do not have to punch clocks, do they? Are you punctual? What does being punctual mean? Have you ever worked in a factory?

* * *

3. One Year Performance 1981-1982 — Hsieh lived outdoors in New York City.

Can you know about this piece without thinking of the condition of homelessness? The horror of homelessness? Now you will always wonder if the homeless man or woman you see in the street — or try to avoid seeing — is an artist, or perhaps a saint.

* * *

4. Art/Life One Year Performance 1983-1984 — Hsieh and artist Linda Montano were tied together by a length of rope.

We will stay together for one year and never be alone. We will be in the same room at the same time, when we are inside. We will be tied together at the waist with an 8 foot rope. We will never touch each other during the year.

For anyone who might think that Hsieh is certifiable, here’s proof that he is perfectly normal: In a 2003 Brooklyn Rail interview he complained that Montano had taken too much credit for the rope piece and, in any case, it was his idea: “She took that piece and made it hers. Most people think that was her piece. The picture she always uses I don’t like it either. She is in the foreground and I am in the background.”

This should dispel the notion that there was something Buddhist or Zen about Hsieh’s approach to artmaking.

Montano, a considerable artist in her own right, claims in a 2002 interview she saw one of his posters in the street and heard a voice in her head say: “Do a one-year piece with him.” She also said his “concept ART/LIFE: ONE YEAR PERFORMANCE was inspiring, and when I decided to join him in his rope piece for a year and I got to work with this ‘genius of art’, I learned so much about time from him.”

There’s a report she is now a novice at Maryknoll Sisters in upstate New York.

* * *

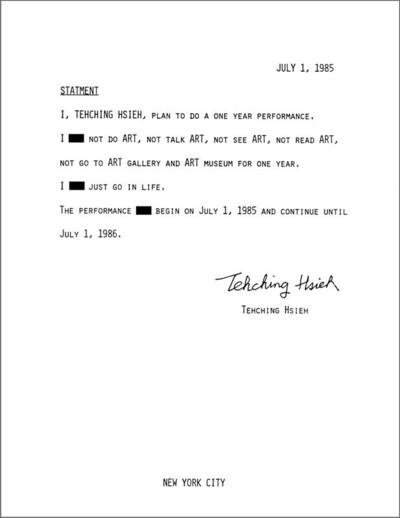

5. One Year Performance 1985-1986 — Hsieh did not view, make, discuss, read about or in any other way participate in art.

Was this in response to being tied to Montano?

* * *

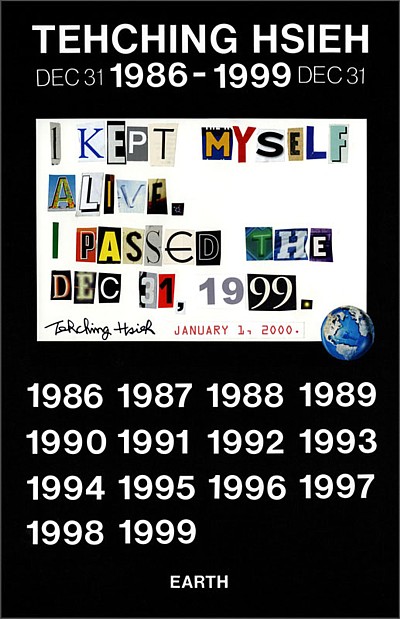

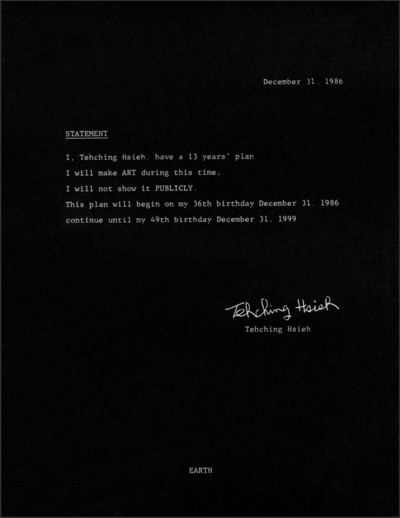

6. Thirteen Year General Plan 1986-1999 — “I kept myself alive.” .

I have included Hsieh’s final piece, though some might question that it has been fully accepted as art. I think it has been validated through the strength of the previous performances. Furthermore, it is — how shall I say it? — subtle. It is not clear, for instance, what artworks he made, if any, beyond just surviving. What is clear is that after this point, Hsieh no longer called himself an artist.

* * *

What Is Originality?

Hsieh claims, in terms of his Taiwan jump, that at that time he did not know of Yves Klein’s 1969 Leap Into the Void, nor had he even heard of that spiritual prankster. But when Hsieh decided to live in a cage for one year in New York City, had he known of Joseph Beuys’ I Like American; America Likes Me? Beuys flew to N.Y.C. and, swathed in his signature felt, had himself delivered by ambulance to the Rene Block gallery in Soho and for three days preceded to live in a caged-off space with a coyote.

It now looks like Klein faked the purported photo of his jump through the magic of the darkroom, which, of course, does not invalidate the metaphysical import. Beuys performed his cage piece in 1974, the year Hsieh jumped ship outside of Philadelphia and took a $150 cab ride to New York City. Beuys’ cage piece did not last an entire year, like Hsieh’s 1978-79 work. Hsieh’s feat did not include a coyote.

I think we can safely dismiss Hsieh’s 1973 “jump” as juvenilia, notwithstanding a poster he made to document this leap. The jump resulted in two broken ankles.

Hsieh’s cage piece is, in its relationship to the German master’s cage piece, quite another story. Whether or not Hsieh knew of Beuys’ artwork is not as important as is his timing. Four years is just enough distance. To spend one year living in a cage as opposed to a few weeks is more than a difference of degree. Furthermore, living alone in a cage with all the overtones and undertones of solitary confinement that this entails sets up meanings far different from the shamanism and the nature/human nature complexities of Beuys’ visionary artwork, which I myself witnessed. Beuys claimed to be making a statement against the war in Viet Nam. Four years later, Hsieh’s complexities were all his own.

If I were to live in a cage for one year, beginning tomorrow and ending a year from now, would that have different meanings? At this point in time, it would be classified as appropriation and probably be dismissed. But leaving appropriation aside, wouldn’t it be an entirely different piece because I am an entirely different person? We know for instance that when Hsieh performed his cage piece he was then an illegal alien. I am not. Hsieh’s self-imprisonment has to be seen at least partially as a metaphor then for his status as an alien — “imprisoned” by isolation and fear and/or his possible future incarceration. Plus all the anguish that existentialism once allowed — in fact, necessitated.

Hsieh has stated that all six of his works are about struggle.

If John Perreault were to live in a cage for one year, one could not avoid the suggestion that it was a symbolic manifestation of being imprisoned by art, or perhaps by an established identity as an art critic, poet, or artist. Plus all the anguish that existentialism allows

If Hsieh himself were to relive his cage piece now, it would also be a different piece: you cannot step into the same prison twice. Only the duration would be the same, if that.

Hsieh’s cage piece, compared to Beuys’ coyote classic, is more minimalist, more self-involved, and in some ways more difficult. Like the one year performance of living outdoors, the Hsieh’s cage piece communicates the radically forlorn, which I tend to think of as a philosophical category.

Hsieh’s six artworks make most art in comparison look weak and pandering, unfocused, bereft of meaning. Where in art has all the rigor gone?

Hsieh’s six works form a natural progression from the fullness of the cage piece to the zero-degree affect of the 13 Year General Plan. Hsieh’s 13 years of nothingness were not like Marcel Duchamp’s, who allowed everyone to think he had given up art but, in fact, was making secret artworks.

On the other hand, Hsieh in 1986 had already made a work that consisted of not making or looking at art, so what could follow? Neither making nor not making, if we dare to imagine such. This is what I hypothesized, but it was not exactly his intention, according to his first statement:

I like my artwork better. I like my misunderstanding. In fact, in 2003 in the Brooklyn Rail, Hsieh was able to make a clarification:

O.K., everything I do is a progression, an evolution like the earlier pieces, it doesn’t make sense. Do you understand? The next logical step was to just surivive into the next century, the new millennium.

Not everyone can or should continue making art for a lifetime. Inspirations come and go; being an artist is a state of being. Art making can become a bad habit or merely a business. Is it possible just to quit while you are ahead? In another realm, is Herman Melville any less a novelist because he stopped writing prose about 1867 and became a customs inspector?

FOR AN AUTOMATIC ARTOPIA ALERT CONTACT perreault@aol.com