Other Worlds

The art world can too easily be seen as monolithic. What is bought and sold as art and makes a profit is the definition of art. Until quite recently, linear, evolutionary lineups were routinely used in exhibition catalogs and critical writings to provide a cursory justification of assumed historical outcomes. This reverse engineering was applied not only to formalist abstraction — where the ploy was coined — but could be jiggered for other styles, even the Dada/Surrealist one: Duchamp leads to Johns, Johns leads to….

But in Artopia, if asked to picture art history, we see a braid of many strands instead of any particular line concocted to verify sales or taste or objectify power. Furthermore, we see the reality of art as existing outside of objects. This rarification may be attained through objects, but this is not necessarily the case.

It may seem that the Art World Proper — as opposed to the Art World Improper, which is synonymous with Artopia — has become supremely product- and profit-centered, but we have hope. Slowly but surely we see the kinds of art once off the map or simply inadequately charted reappear. In truth, the Art World Proper is insatiable. Not only do curators constantly need new fodder to secure their reputations, graduate students have to come up with new subjects for their dissertations. Even art history can be ironic.

In spite of their anti-object, ephemeral profile, performative art forms such as Events, Actions, Street Works, and Performances are beginning to make the grade. No longer are museums so beholden to objects that nothing but stretched canvas and chunks of matter will suffice — leaving craft as the embodiment of materiality, but letting it sneak into the panoply through deceptive labeling. George Ohr pots are in MoMA’s Design collection. A Ronnie Horn thick rectangle of red glass is in Painting and Sculpture. Across the street, the Museum of the Arts and Design, formerly the American Craft Museum, now seems ashamed of the word craft.

And then there’s Latin American art.

Does the Latin American Art World, like the craft world, overlap the Art World Proper, forming a parallel universe of discourse? Doesn’t it also deserve to be another strand in the Big Braid?

Like U.S. and Canadian art, Latin American modernism was inspired by European developments. But aside from the important Mexican mural movement, not much of it represents a shift from the Euro-Modern.

More important, as the international (i.e., Euro-American) styles kept twisting and turning, from Pop to Minimalism and onward, it was difficult to really nationalize the changes of fashion.

By the early ’60s, artists and their art traveled everywhere. Outside the Europe/Americas axis, other art stories and timelines fluoresced. For instance, are we sure what the new art of the last century looked like throughout Asia? But that’s another story, as is rampant globalism — how globalism differs from common internationalism.

Hélio Oiticica, Metaesquema II,1958

Geo-Latino

The modest MoMA sampling of Latin American art — “New Perspectives in Latin American Art, 1930-2006: Selections From a Decade of Acquisitions” (through February 25) — favors abstract art, the best examples of which are the Neo-Concretism of the Brazilians Hélio Oiticica and Lygia Clark. And as the title might suggest to those attuned to such fine points, this cool exhibition does not include much art by Spanish-speaking artists north of the equator.

Most of the art displayed are works on paper, complemented by a few sculptures, of which Oiticica’s Box Boilde 12, 1964-65, and two “variables” by Clark are outstanding. Viewers were originally urged to reach inside and experience the sand and cloth. Here the elegant presentations screams “Don’t touch!” In fact, I had the feeling the nearby guard would arrest me if I tried.

Shown in the third-floor section of the exhibition, Clark’s 1960 hinged Sundial, displayed in a vitrine, is also presented with no indication that it is a variable and can be changed at will. Only when we come upon her Poetic Shelter on the second floor are we informed that her Bichos (Critters) — of which this piece is one of many — are interactive.

We are not offered examples of the later, more important works of either artist: Oiticica’s “Parangoles” (Capes) or Clark’s over-the-top healing ceremonies. I searched for them on MoMA’s website — which, granted, gives you access to only 7,895 of 150,000 artworks– but no “Parangoles” or healing works were in sight. I am not sure at this point if this is because examples were accessed prior to 1998 or there are real gaps in the collection.

(MoMA’s “online collection” is free to all and is a great resource. Most entries include images. Teachers, you can assign curatorial exercises to your minions: For next week, select 30 images of artworks from the MoMA collection, according to your own scheme or theme.)

Are the late works of Oiticica and Clark so difficult to acquire? Or is it that Oiticica commits the sin of tropicalism. Tropicalia, sometimes called Tropicalismo, was a late-’60s, short-lived Brazilian art movement named after an Oiticica art work. Along with Oiticica, Clark and other artists, poets and musicians such as Caetano Veloso and Gilberto Gil joined the “cultural cannibalism” espoused. Central to the cause was the sly embrace and transcendence of Carmen Miranda-ism, enabling Rio’s carioca revenge on Europe and North America — before the group was shut down by the military government. The great Brazilian music stars Veloso and Gil went into exile.

Is it that late Clark is based on Brazilian shamanism, her rituals reportedly effective treatments for schizophrenia, and that she abandoned art to work with the mentally ill? A friend who experienced one of her rituals — in which he was wrapped in cloth and pebbles placed on his eyelids — told me he immediately began to hallucinate.

Although “New Perspectives” is a conservative survey of Latin American art, some concept-oriented works are included, for instance Brazilian Cildo Meireles’ rubber-stamped cruzeiros from the ’60s, but such works are rare. One hopes that the MoMA Latin American collection or future selections will open up a bit to go beyond what looks good to what is innovative and perhaps even a bit troublesome. It seems to be happening in other departments. Just take a look at curator Deborah Wye’s current painting and sculpture collection selection called “Multiplex.” David Hammons’ hairy Rock Head! Jackie Windsor’s Burnt Piece! Nancy Spero! Lynda Benglis!

In the meantime, to counteract the we-hope-unintended MoMA message that Latin American artists have uniformly sidestepped the political or the experimental, one must visit “Arte ≠ Vida: Actions by Artists of the Americas 1960-2000” at El Museo del Barrio, Fifth Avenue at 104th Street, to May 18.

On the Other Hand…

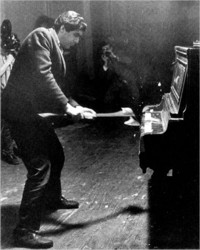

Rafael Ortiz, Destruction Ritual, 1967

Just as Alexandra Munroe’s book Japanese Art After 1945: Scream Against the Sky filled in the Japanese performative-art gap, “Arte ≠ Vida” will do the same for Latin American art. The catalog is supposed to be ready in May, and I advise you to order it now.

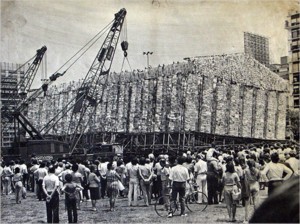

The panoply of excess charted by “Arte ≠ Vida” is the real deal. Through the lens of performative art forms we get a sense of the breadth and depth (and continued relevance) of the Latin avant-garde, from Argentina all the way north to Cuba and Puerto Rico and even Nueva York. Cuba-born Ana Mendieta is included, but is not in the MoMA show (although they have a great piece in their collection). Destruction artist Rafael Ortiz, the founder of El Museo, is shown in full force, destroying pianos — there are even some piano guts on display. And the Brazilian Tunga is here too, represented by his photo of young twins joined by their long braids. This is an Artopia icon! And Marta Minujin’s Parthenon of banned books. Other Artopia favorites represented: Rafael Ferrer from his performance/anti-form days, Alfredo Jaar, and Mexico’s Francis Alÿs.

Full disclosure requires that I point out that although not Latino, I am represented in the El Museo exhibition. I gave El Museo a Xerox of the Street Works flyer I designed in 1969. The curator was interested in works by the Argentine Eduardo Costa — coauthor of the famous Buenos Aires “Happening That Did Not Happen” hoax piece — but who also spent many years in New York. In 1969, along with myself, Costa was one of the five organizers of the four New York Street Works actions that brought artists, poets, and even art critics out on the streets to perform artworks of their own devising. I am also represented in the exhibition by Tape Poems of that year, co-edited with Costa. You can therefore hear sound works by Vito Acconci, Hannah Weiner, Costa, myself, and others.

But how far do we want full disclosure to go? Do you need to know that Ana Mendieta was my graduate student in Iowa City? Do you need to know that I shook hands with Lygia Clark in New York in 1967, when the French critic Pierre Restany brought her around to meet people during the course her hand-shake piece? And that over the years I have routinely shared air-kisses with Marta Minujin?

In any case, curator Deborah Cullen’s gigantic El Museo exhibition — a true blockbuster — sets the groundwork for a better picture of Latino art than MoMA’s Good Neighbor template. First, “Latino” is a more generous, more adventurous and I think more accurate term for the New World Spanish/Portuguese-speaking world of art discourse. There are Latinos in the Caribbean. There are Latinos in our midst, in case you haven’t noticed. This does not mean there are no differences, for example, between Mexican and Brazilian art. But we can worry about that later.

In Artopia, we have it both ways. It is not a question of either an all-embracing transnational art history or a series of particularized national histories. We deserve both, and more. The braid model does not preclude thematic internationalism; in fact, it requires it. A survey of world-wide performative art may now be possible, but this does not nix enriched, time-pegged surveys of all art forms in their raucous simultaneity and their interactive braidedness.

And, oh, by the way, a little bit of criticism. I think the title of the El Museo survey, although paradoxical and provocative, is misleading. Art Does Not Equal Life? In Artopia, at least, art does indeed equal life.

Marta Minujin, Parthenon, 1983, banned books wrapped in plastic

For an Automatic Artopia Alert to new postings contact: perreault@aol.com

John Perreault's art diary