Francis Alÿs, Fabiola (detail) .

Divorce in Art

First multiple Santas in the last Artopia posting and now multiple Fabiolas!

But multiplicity wasn’t invented yesterday, nor by Andy Warhol when he multiplied his Campbell’s soup cans, Marilyns, and Jackies. Think instead of the myriad figures in a Tibetan tanka. Or those dying genres, photo-booth samples and sheets of postage stamps. Admittedly the photo-booth samples are usually images of many different grimacing customers or one-off strips picturing singles or couples in a variety of poses. Andy Warhol based some of his silk-screened portraits on photo-booth pictures (art dealer Holly Solomon, for one), but I am not sure any booths survive.

In terms of Warhol, it was not new to make the same painting over and over. In some sense, Ad Reinhardt was already doing that with his all-black paintings, and almost any artist committed to exploiting a signature image could be so accused. What Warhol did that was different was to lay out silkscreened variants of a single image as one artwork. Some might say that the subject did not matter, it was the repetition that counted. Dumb repetition was the real subject.

Belgian-born Francis Alÿs, presently living in Mexico, until now has been most noted for his Dia-sponsored Thief screensaver (1999)…

and for his 2002 MoMA parade from Manhattan to the temporary MoMA-QNS in Queens. His Modern Procession involved 200 participants carrying art replicas and the actual Kiki Smith across the Queensboro bridge…

Now we are privy to his collection of nearly 300 images of St. Fabiola. Most of the images are paintings, but some are needlepoint and others are emblazoned on cheap jewelry. Alÿs’s Fabiolas are now on display at the Hispanic Society of America (Broadway between West 155th and 156th streets, to April 6. FREE).

“Fabiola” is a collaboration between the Hispanic Society and the Dia Art Foundation. Is it art? Lynne Cooke, Dia’s curator, wrote the informative handout, but curiously avoids the issue. In Artopia we are not timid. This indeed is art. It is found-art multiplied.

Obviously, the Dia Art Foundation is eager to regain a foothold in New York City, searching for renewed visibility and needing a positive spin after the decampment of director Michael Govan for the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the subsequent walk-out and divorcement of Dia Beacon funder Leonard Riggio (founder and CEO of Barnes & Noble).

Fabiola was a 4th-century Christian saint, a protector of nurses and abused wives. A wealthy Roman, according to the oddly condensed syntax of the Catholic-Forum’s Index of Saints, she was …

Divorced from her first marriage after being abused by her adulterous husband. Widowed in second marriage. Friend of Saint Jerome, Saint Paul, and Saint Pammachius. Founded the first hospital in the west. Built a hospice in Porto for the area poor and sick pilgrims. After doing penance for her divorce, she re-entered communion with the church by dispensation of Pope Saint Siricus. Wanted to live as a hermit in Jerusalem, but never managed it.

So why isn’t she also the patron saint of wealthy matrons or of the divorced? Or, as we shall see, of lost paintings? Or of would-be but failed hermits? And I love the last phrase: “Never managed it.” Why not? Would she have had to give up her scarlet hood?

Centuries later her reputation was fueled by the hugely popular The Church of the Catacombs (1854), by a certain Cardinal Wiseman. In turn, this potboiler led to the painting of the now lost, icon-generating Fabiola by the little-known French academic Jean-Jacques Henner. Judging by the copies of copies this fantasy depiction generated, Henner’s St. Fabiola showed her in profile, wearing a scarlet hood.

Alÿs has been collecting these popular replicas of replicas for a number of years. He had thought of flea-marketing for da Vinci’s Last Supper, but there were simply many more Fabiolas.

And here they are: nearly 300 Fabiolas at, of all places, the quaint, wood-paneled North Building Galleries of the Hispanic Society, looking … well, fabulous.

So who is this Alÿs? Although he tends to get others to do his work for him, his output is refreshingly sparse. He avoids a signature style or even format. He has not yet been packaged.

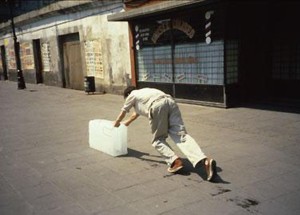

In 1997, he pushed a block of ice through the streets of Mexico City.

Alÿs, The Paradox of Praxis .

For When Faith Moves Mountains (2002), he attempted to move a sand dune in Peru with the aid of 500 volunteers….

What connects these works to Thief? And the Modern Procession?

We await a larger sampling of Alÿs’s art. “Francis Alÿs: Politics of Rehearsal” is now at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles (to Feb. 10).

In the meantime, the Fabiola depictions range from plausible to draw-me-matchbook dull and coloring-book crude. It is the multiplicity that charms. Although most of the profiles face viewer-left, some look stage left as if we are seeing Fabiola in a mirror.

Taking in these Fabiolas is a peculiar way of seeing the original. Imagine if we knew Goya’s 1797 Portrait of the Duchess of Alba (The Black Duchess) only through amateur copies or cheap photographs of less-than-famous actresses dressed as majas.

Fortunately, right there on Audubon Terrace in the Hispanic Society’s South Building across the way is the real Goya maja, arguably the signature artwork of this undeservedly obscure institution. I myself years ago had made a pilgrimage to Washington Heights to see the Duchess. Or was it to see the El Grecos?

Divorce on Parade

Many art lovers, whether tourists or local repeat visitors, go to museums for signature artworks. If art is merely loaned out piecemeal here and there — as patron Eli Broad has now decided will be the case with his 2000-item collection, most of which many assumed would go to LACMA — it is unmoored, divorced from any consistent institutional context and will not really belong to the public.

You go to MoMA to see Manet’s Water Lilies or a particular Mondrian. Or you need your Picasso fix. You go to the Philadelphia Museum of Art to see The Bride Stripped Bare By Bachelors, Even. Or maybe not. Not everyone “owns” the same paintings, but there are certain artworks that are emblems of certain institutions.

So where’s the art? Who’s got the art? Here and there and everywhere, or in storage. Or constantly on the road, which can’t be good for the art. Foundations are quirky entities.

In terms of the Broad “scandal,” as others have pointed out, artists need to beware of the “private foundation Catch-22.” Sales are sales, of course, but a foundation can dump artworks on the market with impunity. Museums at least have a stake in not exposing their mistakes or their need for ready cash in a hot market. Most museums have or should have clear guidelines for their deaccession committees.

I am not saying that Broad will dump artworks; he doesn’t need to. But there is always the next $20 million art bargain just around the corner, and other retired moguls have been known to go for the deal they cannot afford to pass up. Buying and selling is a high.

If Broad really believes in art, he should really start his own museum and make it free to the public. And endow it well enough so that it stays free. Where are the Andrew Carnegies of art? Andrew Carnegie set up free public libraries all across America.

Although the Broad Museum of Contemporary Art at LACMA is set to open thanks to Broad’s $60 million, galleries are naming opportunities for additional donors. For a mere $10 million, Marc and Jane Nathanson will get a gallery named after them. Further happy news: It was just announced that Zaha Hadid will be the architect for the forthcoming Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum at the University of Michigan. Broad’s $26 million covers a little more than half the cost.

Can Art Be Divorced From $$$?

I am usually divorced from these art-world topics, but they keep intruding like unwanted auction news. It used to be that show business was everybody’s business. Now art is.

And while I am at it, I am also fed up with all the praise being heaped upon the now retiring Philippe de Montebello. I suspect his rise to power and his 30-year tenure as director at the Metropolitan Museum of Art has something to do with the hatred accrued by predecessor Thomas Hoving. De Montebello has managed to add some exhibition spaces to the museum and straightened out others. He did the basics: kept the institution from collapse, lawsuits, and outright scandals. He had the good sense to return some stolen artworks to Italy.

But I would like to remind all Artopians of the following: (1) He has never really supported modern and contemporary art. (2) As the Met’s CEO, he has been responsible for annual operating deficits that have recently run as high as $3 million. (3) He oversaw and actively defended the constantly increasing admission price, which is now $20. This tithe is “voluntary,” but it is not readily perceived as such by most visitors.

I did a little research:

Until 1941, the Met charged admission only one or two days a week. In 1940, the admission was 25 cents on Mondays and Fridays. From 1941 to 1979 it was totally free. Those were the glory days, the democratic days.

In 1970, under Hoving, a regular admission of $1.50 was instituted.

I remember how angry I was when the Met started charging admission. It was like having to pay to get into your own living room. I had very little money, but was hungry for art. I suppose I could have paid $1.50 by skipping lunch, but on principle I never shelled out more than a Rockefeller dime, which was the old man’s customary sign of largesse.

Five years later, under de Montebello, admission was increased to $1.75. It was $6 in 1993; in 1999 it went from $8 to $10. Oh, yes, said Philippe back then, they had lost some money once promised by the Reader’s Digest heir. Oh, the fickle rich. And then in 2006, admission moved from $15 to $20.

The Whitney and the Brooklyn museums were once free too. As for MoMA, we never expected it to be free. The rumor was that when old man Rockefeller was asked by his daughter-in-law Abby Aldrich if they should charge admission to her new museum, he answered that no one would appreciate the art if they didn’t.

If we pay $20 to look at art, is it better than the art we can see for free? And if so, would a $40 ticket make the art look twice as good?

I think free art looks better because you have more time to look at it. You don’t have to rush through to get your money’s worth. You know, if it’s two o’clock, I must be in the Greek and Roman Galleries. If it’s three, I must have already covered the Renaissance.

Therefore:

If I am elected mayor of New York on the Pro-Art Barnett Newman Party ticket, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which is housed in a city-owned museum and receives free heating and electricity, will be free to all, with no challenges like the tiny Pay What You Want But Pay Something sign. The hard-working citizens of New York and even the tourists on their Euro spree already pay their share by way of the city sales tax.

For an Automatic Artopia Alert for each new posting contact: perreault@aol.com

John Perreault's art diary