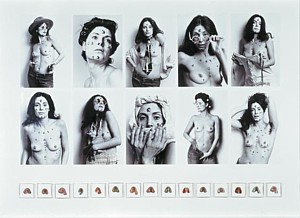

Hannah Wilke, Untitled, 1974. Photos and chewing gum. (not in exhibition)

Death Isn’t Fun

Sometimes art takes time. Time is distance. Some art is best seen later, in the past tense. Or if not exactly in the past tense, since all objects and images are technically present-tense, then “once removed.”

Hannah Wilke (1940-93) made that kind of art. Ironically, at first glance, her art was all about herself, all about her body, and was open to the charge of narcissism. Now it seems likely she was making fun of her body, of physical beauty, and male obsessions. Her attack on art history and patriarchy was oblique, but nonetheless pertinent. In retrospect, Wilke’s work was about morality — insofar as it exposed male objectification of the female body — and then mortality. Is not physical beauty all the more beautiful because we know it cannot last? Oh, how many poems have been written about that.

The key work in the current exhibition at Feldman (31 Mercer Street, to Oct. 13) is Intra-Venus Tapes, 1990-1993. It consists of 16 flat-screen monitors, in a four-by-four grid, showing 30 hours of tapes of Wilke’s last days when she was being done in by lymphoma. Completed according to her instructions and 14 years in the making, the Intra-Venus Tapes installation is sad and vividly antiromantic. Death is not fetishized. The sound jumps from one screen to another. There she is with her bandages. There she is being cheerful. There she is bloated and comatose. It is hard to take, yet a photo blow-up across the room confirms her lingering beauty, as do several of the tapes.

There are many things you need to know. Wilke once did a shocking series of photographs of her dying mother. But you also should know she made tiny vaginas out of chewing gum, sticking them to herself and onto photo self-portraits. That and her glorious body were her fame.

I knew her, but only in the way, back then, that a critic would know someone on the scene. She was always cheerful, always fun — unless she was obsessing about a former lover whom she claimed ripped off her earlier foray into assemblage handguns. And, yes, she was always beautiful.

If you’ve got it, flaunt it.

But beauty can be a burden. Here I have a delicate task. I won’t go into how Carolee Schneemann, a body-art elder, has always transcended her own beauty without denying it. Instead, so you will not think I am singling out women, I will have to note that male artists can have that handicap too. Willem de Kooning was always thought of as handsome, and he was, right to the end; but his booze-inspired Mr. Hyde apparently balanced his Dutch Boy good looks.

Flash-forward to the early ’70s: Another painter, much younger, was one half of a super-beautiful art-world couple. No one took him seriously, despite his obvious talent. He was too handsome. Years later he reemerged as if from a cave. He wasn’t any shorter, but he was scruffy, ill-groomed and had put on a bit of heft. He no longer looked like an actor or a male model. He had substance. Now we could see his art. And — we all love happy endings – his paintings are widely admired.

But in an art world in which male superstars routinely benefit from plastic surgery, perhaps the rules have changed.

Going back in time to establish a context for Wilke’s art (so, I hope, we can transcend that context), her art was seen in the family of other body art by women: Lynda Benglis’ notorious Artforum ad showing her sporting a giant dildo; the earth-body performances of Ana Mendieta; and, as always, the remarkable Schneemann, who in one of her nude performances pulled a typed text out of her vagina. Oh, those ’60s and, oh, those ’70s. After streaking, Ann Halprin’s nude dancers, Kusama’s naked street-actions, and Broadway’s full-frontal Hair, nudity was everywhere. Vito Acconci plucked his pubic hairs and in another piece hid his penis between his legs. Robert Mapplethorpe stuck a whip handle up his butt. But not until John Coplans (LINK) photographed his aging body did male artists bare all for art.

Women artists, with less to hide, embraced nudity. Some said this was to exploit/expose the dreadful male gaze. Turning the tables on men, feminist painters such as Sylvia Sleigh were getting their male models to strip, as was the naughty Alice Neel. Yours truly gladly participated, turning their art, post factum, into mine.

Some feminists, however, could not stop castigating female nudity, thinking it somehow acquiesced to traditional male exploitation. Puritans don’t understand irony. Judy Chicago’s vagina-plated Dinner Party drove everyone crazy. We are not just cunts, screamed one woman friend when I praised Chicago’s work. How would you like to be reduced to your cock? At the same time, in order to correct socially induced female self-loathing, other feminists were holding flashlight-and-mirror parties to have a look-see down under. There is no doubt the slang word for the vagina is pejorative; but to call someone a prick is not exactly complimentary either. When it comes to being awful, men and women are equal, but, of course, until recently men have had all the power and could afford to be more dangerous.

When I look at Wilke’s art, I see all of the above. Plus Marcel Duchamp. Yes, Duchamp. Isn’t the bride who strips herself an answer to The Bride Stripped Bare by Bachelors, Even? What this does to alchemy is another question. Aren’t Brushworks #1 and Brushworks #18, made of the artist’s hair, an answer to Duchamp’s early-20th century star haircut? That Wilke’s hair fell out because of chemotherapy and Duchamp’s star was shaved into a negative on his healthy scalp is telling. Which says more? Unlike Mr. Dada, Wilke seems to be saying: I am grounded, I know my mother’s death and am now facing my own. Her 10 large monoprints are self-portraits that show fear and disintegration.

Wilke, Untitled Monotype, 1987.

At last, alas, we can compare Wilke to Frida Kahlo, who is known far and wide for images of her own suffering and is now more famous, more iconic than her husband, muralist Diego Rivera. However, Wilke to her credit resisted the mythologizing that is Kahlo’s egotistic failing.

And finally, although they are not in the current show, we can see Wilke’s chewing-gum vaginas as mouth/vagina constructs, as “rhymes” — hey, you guys — with the vagina dentata.

Death is always with us. How many artists with AIDS have had their bodies photographed? How many have shown their battles with cancer? We do not romanticize these illnesses, as we shall not romanticize Wilke’s late medicalism. We are not Victorians who tried to put a swoon or a spin on tuberculosis or influenza. After all, if cancer or Alzheimer’s doesn’t get you, there’s always the unexpected laundry truck that did in Roland Barthes.

Nor shall we any longer blame the victims and see all ills as somehow caused by not thinking right, by not eating right, by repressing our libidos or by being a bad person. Villains are sometimes perfectly healthy. If art is to be about life, then it is unavoidable that it is sometimes about death, lingering, painful, unfair death.

Wilke, Intra-Venus 7, 1993.

For an Automatic Artopia Alert announcing new entries: contact, perreault@aol.com

John Perreault's art diary