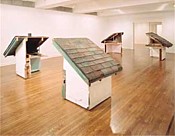

Gordon Matta-Clark: Splitting: Four Corners, 1974 (Courtesy, SFMoMA)

1. Gone Too Soon

Several themes are suggested by the Gordon Matta-Clark exhibition now at the Whitney (945 Madison Ave., to June 3, 2007), not the least of which is the early-death conundrum. Why do the best and brightest seem to die before they are 40? Here’s a list: Eva Hesse (1936-70), Robert Smithson (1938-73), Matta-Clark (1943-78), Ana Mendieta (1949-85).

Many without talent die young too, and perfectly decent artists go on and on. Some even continue to produce credible work, although few indeed have Matissean late-life flowerings. Perhaps de Kooning. Pollock, of course, went out in his prime. And is that where the valorization of early expiration comes from? Or do we have to go back to John Keats, who was dead at 26?

Some have opined that an early death limits inventory and therefore raises price-per-piece on the well-worn principle that short supply plus high demand equals high return. Yet, contrary to this, I have heard that collectors like a lot of stuff floating around to show that the artist was/is a player. The potential for profit is even higher when there is a surfeit of merchandise at hand.

Perhaps more artists should impose on themselves a symbolic early death, in the manner of Marcel Duchamp who went “underground” around the ripe old age of 36. And before him there was poet Arthur Rimbaud, who quit writing at 18 and became a gunrunner in North Africa.

If artists stopped while they were ahead, we would be saved the spectacle of talents repeating themselves for the market and diluting whatever innovations made them visible in the first place. And we’d be spared the sadness of artists who once were good, who once were great.

Early death, even by cancer (which is what took Matta-Clark at the age of 35) makes a more dramatic story than expiring in a nursing home at the age of 89. Of course, if you live to 105, like Beatrice Wood — that’s another kind of story.

Dennis Oppenheim, Annual Rings, 1968

2. The Second-Generation Syndrome

Matta-Clark was a second-generation earth artist, but one who carved buildings instead of landscapes. In fact, as a architecture student at Cornell, he assisted Hans Haacke, Dennis Oppenheim, and possibly Smithson in the famous 1969 Earth Art exhibition. Oppenheim made circular “cuts” in the ice of a frozen lake; within a few years Matta-Clark was making cuts in buildings.

The art world does not like second generations. “Second generation” sounds second rate. My theory is that second-generation Abstract Expressionism was so awful it ruined it for all future second generations. I will not give you names. You know who they are, or if you’re lucky you don’t.

Second generations are anathema. What happens now is that we need to skip a generation and add a prefix. Neo-Pop is O.K.. just as Neo-Dada before it seemed perfectly sensible, although in the latter more than one generation was skipped.

First is not always best. Except in the art world, which is not a reasonable place. First is best because first can be proved, whereas best is a matter of taste. Too often one hears otherwise perfectly swell artists raging about having been the unacknowledged first to….you name it. Drip paint. Paint comic strips. Use silk-screens for paintings. Eschew the pedestal. Use a bulldozer or a chainsaw to make sculpture.

Matta-Clark was held back at the time he was making his breakthrough building cuts – now iconic and perennially influential – because (1) some thought he was copying the earth artists; (2) his sponsors for the remarkable Splitting of 1974, in which he cut an awful New Jersey house in half, were the collectors Horace and Holly Solomon. I liked Holly a lot even when she opened a gallery, but she had studied at the Actors Studio, was fashion-conscious, and was never taken as seriously as Virginia Dwan. Dwan came from Hollywood royalty and was able to scoop up most of the Big Boys of Minimalism and Earth Art, leaving them to John Weber when she closed. And….

Matta (Roberto Sebastián Antonio Matta Echaurren). (Chilean, 1911-2002). Listen to Living. 1941. Oil on canvas, 29 1/2 x 37 7/8″ (74.9 x 94.9 cm).

MoMA, Inter-American Fund. © 2007 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

3. The Silver Spoon

Matta-Clark’s father was Matta (Roberto Matta Echaurren) the celebrated surrealist painter from Chile, who was one of the links between Surrealism and Action Painting. If the illusionistic surrealism of Salvador Dalí was first generation, then Matta’s wild, nearly abstract, sci-fi surrealism was second generation.

Shortly after the birth of the Matta twins (Gordon and Sebastian), Papa Matta divorced his American wife, Anne Clark. Later Matta-Clark did later spend time with his father in Paris, who urged him to be an architect. Matta pére had studied with Le Corbusier, but bailed out of that dismal art. Nevertheless, he recommended to his son that he seek out his old New York friends Frederick Kiesler and Philip Johnson.

Matta-Clark did graduate from the architecture program at Cornell, but, like his father, he preferred art, specifically sculpture, as opposed to painting. The closest he ever got to theory was to call his project “anarchitecture,” which takes on additional meaning when you read Spyros Papapetros’ excellent and playful catalog essay (“Oedipal and Edible: Roberto Matta Echaurren and Gordon Matta-Clark”). Matta-Clark’s father urged him to buy a house or a loft so that his mother and twin brother would feel secure.

Sebastian fell to his death out of a window of his brother’s loft.

a. Matta-Clark: Circus, 1978

b. Picabia: Tres Rare Taleau…, 1915.

c. Deborah Remington, Untitled, n.d. (c.1966?)

4. Documents Become Products

How are we to look at Matta-Clark’s color Cibachromes? They document various cuts. They are, we learn in the catalogue, blow-ups of tiny collages the artist made from 35mm positives. They are what we know of the sponsored building alterations, but they are more. If you squint, they look like Deborah Remington paintings, which in turn remind us of certain obscure mechanistic paintings by Picabia.

I am not alone in pointing out that the Cibachromes were Matta-Clark’s answer to the documentation question raised by Earth Art and other nongallery manifestations in the late ’60s. Smithson invented non-sites: bins and piles of rocks accompanied by banal snapshots and maps. Jan Dibbets began making multiple photographs the point of his art. The parts were assembled into geometric forms.

Unless we recognize Matta-Clark’s Cibachromes as the artist’s reinterpretations of no-longer-existing architectural interventions, they are merely handsome photographs. If one approached the work from a photography p.o.v., you could say that the chain-saw holes cut into floors and walls are only set-ups for the Cibachromes, which provide multiple points of view.

I’d give them a place of high honor in my imaginary exhibition that documents Late Cubism: de Kooning’s “Women,” all of Louise Nevelson, and 99% of Robert Rauschenberg’s gigantic oeuvre.

This is why this little essay is presented in six parts and from six different points of view or six themes..

The difficulty is that as far as I can tell, the Cibachromes take as their subjects the commissioned, legal carvings. The urban guerrilla works, the illegal interventions Matta-Clark made in Bronx tenements and a notorious Hudson River pier known as a site for public sex, are subsumed.

* * *

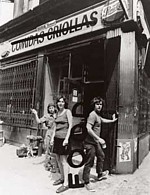

Tina Girouard, Carol Goodeen, and Matta-Clarks in front of Food restaurant, 1971 (courtesy of Matta-Clark Estate and David Zwirner)

5. Lost Horizons

Wallace Berman and His Circle (at NYU’s Grey Gallery) stirred my interest in art groups. Reading the catalog for the Matta-Clark exhibition made me wish for a Greene Street exhibition. I don’t think Matta-Clark took a leadership role in the early Greene Street days of SoHo, the way Berman did in Los Angeles in the ’50s, but there were artists I remember.

Had SoHo even been named yet? Artists I knew and at least one minimalist composer had slide-away beds, hidden stoves, closet showers. It was still illegal to live in those ratty, old loft buildings that now only millionaires can afford.

First there was 98 Greene Street, which was mostly Holly Solomon’s theater project, but I remember Thomas Lanigan-Schmidt getting a drag queen in widows weeds to kneel for hours in front of an ornate altar he had made of tinfoil and bangles. Then the artist Jeffrey Lew fronted the 112 Greene Street gallery and performance space. Others in the informal group were Richard Landry, Richard Nonas, Jene Highstein, Suzanne Harris, Roger Welch, Tina Girouard (who was one of the Matta-Clark’s FOOD restaurant collaborators), the poet Ted Greenwald, dancer Trisha Brown, and Alan Saret.

6. The Alchemy Problem: Gordon Matter-Clark

One might think that because the early work involved mold and food, the transformation of garbage into art, and the FOOD restaurant, Matta-Clark would be a likely alchemical suspect. Also, rumor had it that Marcel Duchamp was his godfather. Matta pére certainly knew Duchamp. According to the collector Arturo Schwartz alchemy was Duchamp’s secret inspiration. We even have lists of specialized books Duchamp may have read when he was working in a library in Paris as a young man.

We already know of this exchange at a Cordier-Ekstrom Gallery opening of Duchamp’s oddments:

Robert Smithson: Oh, I see you are into alchemy.

Marcel Duchamp: Yes, indeed.

Matta-Clark, knowing what materialists his heros like Smithson were, denied being an alchemist. However, we now know from Tina Kukielski’s oddly titled catalog essay (“In the Spirit of the Vegetable: The Early Works of Gordon Matta-Clark”) that books by Jung were in the artist’s library, as were books by Ouspensky and Gurdjieff. But didn’t everyone in the ’60s and early ’70s read Jung, Ouspensky, and Gurdjieff? Reading Jung doesn’t make you an alchemist. Reading Ouspensky and Gurdjieff doesn’t make you a mystic, any more than reading Shakespeare makes you a poet.

Which leads me to the library problem.

If you do not want to leave any traces or clues, get rid of your books before the art historians get a hold of them. This is a new trend: examining the contents of dead artists’ libraries. I first became aware of it with the catalog for the 2005 Smithson exhibition and was inspired to write a little essay for Artopia about books and my own library.

So that no one will be mislead and in the interest of privacy, I am seriously thinking of secretly selling off my alchemical tomes; my books by Rabbi Nachman and by Ibn Arabi. My Zohar has long been given away.

And why would anyone be certain that Matta-Clark actually read the Gurdjieff on his shelf? Although I own the Alchemical Writings of Edward Kelly (who had his hand chopped off for thievery and was magus John Dee’s right-hand man and skyrying partner), I have never been able to read more than a sentence or two: “But among metals there is no form more vigorous or powerful than that of Saturn, and therefore the solvent of Saturn must be sought in the vegetable world.”

By the way, isn’t all art about the transformation of matter, turning dross into gold, which in turn is a symbol for personal transformation?

Matta-Clark used a chain-saw to turn bad houses, tenements, abandoned piers, and office buildings into temples—letting the light shine in. Chunks of this architecture may have ended up in galleries and museums, but like the attractive Cibachromes, also on display at the Whitney, we only know the art, which was an action, by the static residue.

Matta-Clark, Day’s End (Pier 52), 1975.

FOR AN ARTOPIA ALERT WHEN NEW ENTRIES ARE POSTED

CONTACT: jperreeault@aol.com

ALSO NOTE: Past entries can now be searched; see top right. Also go to: ARCHIVE for retrieval by month or headline.

John Perreault's art diary