Aleister Crowley, 1875-1947

Once Was Wicked

By the time you read this, the exhibition of elegant, out-there drawings by the infamous Cameron may be closed (Nicole Klagsbrun Gallery, 526 West 26th Street, No. 213, through February 10). I usually post my essays inspired by current exhibitions while said offerings are still available. But this time around I made an exception.

I wanted to beat the New York Times and the Village Voice on the David Hammons show, and I needed time to read through Aleister Crowley’s Diary of a Drug Fiend, 1922. Down below, you’ll see why.

Crowley’s Book of the Law (1904), supposedly dictated by an angel, is available on the Internet. It is a wee bit obscure. Diary, on the other hand, is over the top and entertaining in an appalling way. According to a friend of mine, who should know about such things, it perfectly captures the bliss and then the degradation of cocaine and heroin. The two narrators are, of course, totally unreliable in this modernist or postmodernist romp disguised as a Victorian cautionary tale.

Now, when I see East Village junkies on the street or hopheads in a Target off the L.I.E., I’ll know what’s going on in their minds, and their lives, and why they think nobody notices their party. Crowley’s cure, in the final “Purgatorio” section of Diary, is less convincing, although the list of excuses offered for taking drugs is both hysterically funny and definitive —

From:

1. My cough is very bad this morning.

(Note: (a) Is cough really bad?

(b) If so, is the body coughing because it is sick or because

it wants to persuade you to give it some heroin?

To:

27. …Suppose I take all this pains [sic] to stop drugs and then get cancer

or something right away, what a fool I shall feel!

I then learned from Roger Hutchinson’s level-headed Aleister Crowley, The Beast Demystified (Mainstream Publishing) that Crowley was able to maintain his heroin habit by medical prescription until his death in 1947. Seems he was given heroin in his youth as an asthma cure. As someone once said, physician, cure thyself.

The inspiration for several novels and short stories, magus Crowley once tried to hijack the Golden Dawn brotherhood from poet W. B. Yeats, founded a “religion” called Thelema, and was called the wickedest man in the world. According to his deathbed nurse, his last words were either “I am perplexed” or “Sometimes I hate myself.”

* * *

Cameron as the Scarlet Woman

Your Muse Appears

I was more than intrigued by the Cameron (1922-1995) presence in the “Semina” exhibition at the Grey Art Gallery, so seeing the exhibition at Klagsbrun was a given. And sure enough, the art topics just flowed. Topics? Problems would be a better term. Not problems in the negative sense, but problems as in geometry or algebra. The big problem is: Must you separate the art from the artist? Can you?

I need to confess that after seeing Curtis Harrington’s short film The Wormwood Star (1955) in the Klagsbrun Gallery, I was hooked on Cameron’s image. She is shown in her studio among her now lost or destroyed artworks reciting some of her writings. Even on the gallery’s small monitor, she dominates the room, the gallery, the building, the block, and all of Chelsea. Not all of Manhattan, mind you, but certainly all of Chelsea.

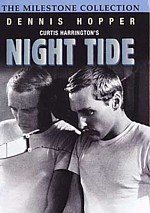

So I rented “cult director” Harrington’s full-length fiction-feature Night Tide (1961). The young and handsome Dennis Hopper plays the sailor in love with…I won’t be a spoiler. Let us just say that the object of his attraction makes her living by sitting in a tank of water on the Santa Monica pier. Cameron plays the mysterious woman calling back the heroine to her watery roots. We do not remember Linda Lawson’s Mora, but we certainly remember Cameron’s Water Witch.

Then, being a scholar, I had to rent Kenneth Anger’s Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome (1956), in which Cameron, as the Scarlet Woman, upstages Henry Miller’s onetime paramour Anais Nin. Yes, Anais Nin.

The film, which involves a lot of posing, posturing, and the swallowing of necklaces and gems, builds to a ritualistic climax of luxurious superimpositions. These days, it does seem, alas, like stoners playing dress-up, but Cameron burns a hole in the screen. Aside from wearing a cape once worn by Rudolph Valentino, she is almost too real. She was certainly not afraid of using lots of eye makeup and staring right into the camera with those lucid eyes.

After Cameron’s marriage to rocket scientist Jack Parsons (whose “working” he thought had summoned her), our art witch spent some time in a Swiss convent and then the arty Mexican village of San Miguel Allende, where she met Leonora Carrington, the surrealist painter. Co-curator Michael Duncan, who wrote the informative Klagsbrun catalog essay, sees Cameron’s art as related to Carrington’s.

Cameron returned to Parsons. I guess the art colony in San Miguel was too rarified. In 1952, Parsons, a disciple of Crowley, was killed by an explosion in his garage — an explosion that is usually called “mysterious.” How could an explosion be “mysterious” in comparison to trying to make an homunculus using the Enochian calls of the Elizabethan magus John Dee?

I dare not tell you what science fiction author, in the “Babalon working,” played Edward Kelley to Parsons’ Dee.

After Parsons died, Cameron “retreated to the desert of Beaumont, California for a kind of ‘vision quest,’ living for a while in an abandoned canyon without water or power,” reports Duncan.

We have already related the tale of Marjorie Cameron’s 1955 tangle with the L.A. police over her “lewd” peyote-inspired drawing. She and artist Wallace Berman vowed never to show in a commercial art gallery again. Later she torched a lot of her work and then made it known that she did not want what remained shown until after her death.

So with a life like that, how can we look at the art? Well, tenderly, cautiously. Perhaps Parsons’ 1946 desert ritual worked. After World War II, the empowerment women gained through serving in the war effort lingered and slowly began to flower. The women in post-war noir emblemized men’s fear, but the so-called Scarlet Woman could not be stopped.

Cameron, Crucified Woman, n.d.

The angels and demons in Cameron’s trippy drawings release a perfume we have not experienced before. Certainly not in the academic surrealism of Carrington, whose charm has always escaped me. The surrealist Pope Andre Breton flirted with occultism. Cameron lived it.

Cameron’s drawings, now coming slowly into public view, are in some ways outside art. They are about the power of the images rather than the forms. They resonate with the art of the insane, the drug-addled, the homeless outsider, and perhaps the visionary art of someone like William Blake. Her demons, angels, and horny women are almost too Goth to be true.

Now ye shall know that the chosen priest & apostle of infinite space is the prince-priest the Beast; and in his woman called the Scarlet Woman is all power given. They shall gather my children into their fold: they shall bring the glory of the stars into the hearts of men.

— Aleister Crowley, The Book of the Law.

Cameron, Untitled, n.d.

IF YOU WISH AN E-MAIL ALERT FOR FUTURE ARTOPIA ENTRIES CONTACT:

perreault@aol.com.

John Perreault's art diary