Holiday shopping in P-town

How Provincetown Became P-Town

Because I was writing this in the middle of the holidays, I thought at first it would be a simple piece about my little trip to Provincetown, Massachusetts, where indeed I did see some art. In Artopia, every holiday is a busman’s holiday. You cannot escape from art. And when it comes to art, nothing is ever simple.

P-town, as it has been called from Charles Hawthorne to John Waters, was once an active and important art colony. Hawthorne, then Hans Hofmann, had summer art schools there. I own two “mudhead paintings” from Hawthorne’s summer school, which he started in 1899. They are still lifes on canvas board of some sort, abandoned and used as insulation. Discovered when a house was being renovated, a collectibles dealer got a hold of them and offered them for sale, cheap. I got the last two. Hawthorne made his students paint in harsh daylight, head-on. With a palette knife or a broad brush, they had to indicate broad areas of light and shade.

After World War II, Hofmann, a German expatriate, attracted would-be modernists to his summer school in Provincetown and somehow convinced everyone that the “push-and-pull” of planes and brushstrokes was the only way to paint. Thus he damaged an entire second generation of Abstract Expressionists and furthered the reach of cubism. Yet what he really was teaching, like Hawthorne before him, was a belief in art.

And painters such as Edwin Dickinson, Edward Hopper (who held out in nearby Truro), Franz Kline, and Robert Motherwell all had studios. But the P-town artists, and poets, and playwrights, are legion, are legendary. Eugene O’Neill and Tennessee Williams had creative breakthroughs there. And all sorts of rowdies, from John Reed to Divine, spent time in the wilderness, rejected as unsuitable for agriculture by the Mayflower elite. Instead of planting wheat in the sand or harvesting oysters, our infamous sourpuss Pilgrims stole the Indian corn cache and then moved south to boring Plymouth Rock.

This delight, this land’s end, this Provincetown became a fishing port with salt farms and fish-drying racks in every front yard; a rickety, winding length of wharfs; a haven for pirates, privateers, and rum-runners — and eventually wild-eyed artists of all sexes. At one point, you could build a shack of driftwood in the Sahara-like dunes and just squat. De Kooning, Pollock, Ginsberg and many others stayed in these dune shacks. As did I, only three years ago. A few of these charming concoctions, you should know, have been preserved by the U.S. Parks Department as part of P-town history and are available as juried residencies for artists and poets.

Art colonies were where artists summered in relative freedom from the constraints of cities and bourgeois sensibilities, which were seen as contrary to creativity. The positive connection between carousing and making paintings or writing poems has never been proved, but painters and poets, like most people, will grasp at any excuse for fun: the landscape, the light, the picturesque locals.

To have art colonies, you have to have artists as outcasts, which, of course, really didn’t happen until Romanticism. But now, because of the lifestyle revolution, artists aren’t outcasts anymore. Mothers and fathers used to weep when their offspring announced they wanted to be artists. Now the folks just send their kids to Yale and put a down-payment on a loft.

But why would artists want to hang around with one another? The past is a weird place. Artists used to cluster. Certainly, a common belief-system would explain a lot, along with mutual protection, sharing information, hopping on to one or another stylistic train, mate-swapping, binge-ing, philandering and the thrill of hand-to-hand competition. Artists learn from each other. And, according to Romanticism, they need inspiration: a muse, a myth, a drug, or a landscape.

Pilgrim’s Monument, Provincetown

We Romantics

A few weeks ago we were in Provincetown, off-season again, which is our habit. Even good friends continue to look puzzled, just as they were puzzled by our frequent visits to Iceland. We like the air in both places, and when the P-town tourist season — longer and longer each year — is over, you can actually stroll Commercial Street unhampered. Shops are closed-up tight; foghorns at night; not even a hint of hip-hop or disco versions of Patty Page singing “In Old Cape Cod.” Actually, the Wellfleet oysters and cod are at their best.

One May, we house-sat in nearby Wellfleet. The place came with an oyster license, a wire basket, and an oyster ring to keep our treasures within the legal oyster size. We gathered a bushel from the murky estuary one morning. But it now seems the winter Wellfleets — we had them at the expensive Red Inn at the western end of Commercial where the Pilgrims landed in 1620 — are saltier, plumper.

The first winter my partner and I visited together, we were house- and dog-sitting. I later wrote a short story called “Do Not Drive on Breakdown Lane” (the message you see on signs along the road to the Lower Cape); it’s in my collection of short stories called Hotel Death and Other Tales. Not in “Do Not Drive” is our Woody Allen moment: trying to get at the sweet meat of our very own New Year’s Eve steamed lobsters without the proper tools. Panic ensued, but I luckily found a hammer and an ax in the toolbox on the back porch before the bright-red corpses totally cooled.

I grew up on the Jersey Shore, so I have always liked resorts off-season. There is far less of the them-versus-us vibe, and the beaches are bereft of the horrible odor of suntan oil. Since P-town is 30 miles out to sea at the end of Cape Cod (and thus closer to the Gulf Stream, than, say, Coney Island), the winter weather tends to be a bit milder and certainly less polluted than the uninformed might expect. Recreational vehicles are controlled and there is not a glut of motorboats and yachts to soil the pristine sands with globs of crankcase oil and other bad stuff, as on Fire Island, where I find petroleum-infused sand for my seascape paintings.

The P-town air is now as important as the justly celebrated light, beloved by painters since the 19th century. P-town is a kind of natural Spiral Jetty, so although it is sometimes difficult to tell if you are facing west or east or north or south, on well-lit days the light reflected from the ocean side and the bay side comes at you uniformly and lifts your spirits.

,,,At the very tip of Cape Cod: Provincetown from the air

Where’s the Art?

I dropped in on the Provincetown Art Association and Museum, founded by artists in 1914 and now sporting a beautiful and energy-efficient new wing that has been awarded a Silver LEED rating by the United States Green Building Council, the first to a museum. Shows on view were “A Perfect Freedom: Continuing the Legacy of the White Line Print” (now closed) and “Recent Gifts to PAA,” which included a splendid Evangeline by the always mysterious Edwin Dickinson (1891-1978). Was this once-celebrated Provincetown artist a conservative or a visionary? Robert Beauchamp (1923-1995) and Fritz Bultman (1919-1985) were also nicely represented. Also of note were drawings by Blanche Lazzell (1878-1956) under the influence of Hofmann’s latter-day cubism.

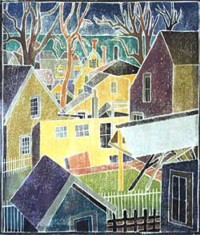

Lazzell had been one of the best practitioners of the Provincetown single-block, white-line, multicolor wood-block print. Although B.J.O. Nordfeldt (1878-1955) actually invented this distinctive technique during the winter of 1915-1916, it was mostly women who filled in the blanks, as it were. Unlike the standard woodblock print — let’s say by Hokusai — which requires a different block for each color, the Provincetown print uses one block, and the color areas are separated by linear incisions that result in distinctive white borders, the ink applied separately to each area.

Was “A Perfect Freedom,” which commandeered teachers from Nausett Regional High School, an attempt to revitalize the white-line print by passing on the technique? I would think additional strategies might be classes for adults at the PAAM and perhaps scholarships and residencies for artists who want to acquire this extremely attractive printmaking vocabulary. What would Jasper Johns or Alex Katz do with the white-line print? In any case, the identifying white line and flat areas of colors make most of the prints, no matter what the date, look modernist indeed. The still-preferred subject matter (P-town’s cozy streets, dunescapes, seascapes and the inescapable Cape Cod light) matches the white-line look. The exhibition — curated by the teachers — added to the new works, splendid prints by P-town old-timers such as Lazzell, Ellen Ravenscroft (1885-1949), Grace Martin Taylor (1903-1995), Norsfeldt himself, and the neglected modernist Karl Knath (1891-1971).

Blanche Lazzell: Provincetown Backyards, 1926. White-line print

Also on view was the Annual, a show of Provincetown artists once the occasion for battles royal between the traditionalists and the abstractionists. Now anything goes. As usual, all members of the PAAM qualify, so it is a dizzying, democratic mess. Will the Robert Beauchamp, the Robert Motherwell, the Franz Kline of the P-town present emerge? Hard to say. The town’s commercial galleries, many still open for Christmas traffic, offered no answer, alas, to that question.

Machado and Silvetti Associates, PAAM (new wing and entrance)

Artopia Is the Art Colony of the Future

Artist colonies in the U.S. once abounded: New Hope, Woodstock, East Hampton, Taos, Santa Fe, Provincetown, and even — albeit briefly, with the summerings of Charles Glackens and his ilk — Bellport, Long Island, my beloved Tilling-on-the-Bay. Art colonies were pretty much seasonal, were always picturesque in one way or another, and were affordable for artists and other artistic ne’er-do-wells.

Historic art-colony sites are now high-end real estate. Aspen? You have to be kidding; bartenders need to live in trailer camps 30 miles down the side of the mountain.

The bone yards of former art colonies and/or communities now attract the super-rich. Why does Tribeca now sport the most affluent zip code in Manhattan, winning out over the Upper East Side? According to my successful realtor friend, most of her customers want to live the fantasy life of artists and they imagine that Tribeca is still bohemian or avant-garde.

There are no more art colonies because we no longer need them. We fly here; we fly there. We form our own little art networks. There are no art colonies for the same reason there are no art bars. Where is the Cedar Bar or the Max’s of yesteryear?

Young artists used to pray for Pollock, de Kooning, or Barney Newman sightings. Nowadays, I don’t think anyone would blink an eye at spying Jeff Koons or Matthew Barney. Every artist is now the star of his or her own movie.

No one wants to talk. If you go out, you go to a club to dance your brains out. Art now is serious business; you cannot risk being seen drunk in public, being heard saying something passionate — or saying something really, really stupid. Groupies might be carrying guns. Your image is all.

FOR AUTOMATIC ARTOPIA ALERTS WHEN NEW ENTRIES ARE POSTED CONTACT: