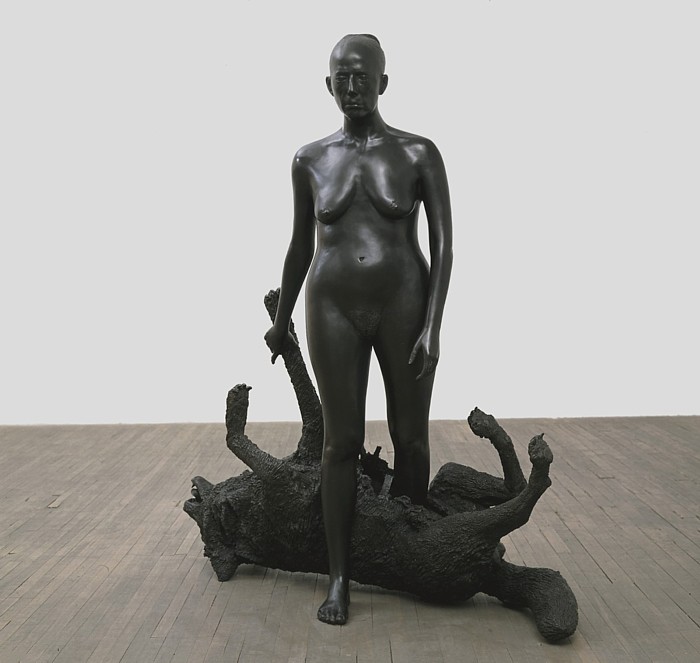

Kiki Smith: Lilith, 1994. Siliconbronze and glass.

Most art critics and art journalists avoid art issues. The products are described, sometimes adequately, sometimes not. Meanings are avoided, possibly because in most cases there are none. This might have been understandable in a time like the ’80s, when art issues almost sank the ship, but nowadays, when the only issue is whether or not the art fairs will kill off Chelsea, we could use a few issues again.

“Kiki Smith: A Gathering, 1980–2005,” which originated at the Walker Art Center and is now at the Whitney in New York (through February 11), brings up a lot of issues that some, I fear, would like to forget. That there is more going on in Smith’s art than in the luxury products or investment markers now being offered in most galleries drives some people nuts.

Just when you thought all that feminist stuff had disappeared, here it is again. And more. To put it bluntly, does the body as an art topic still have legs? Is sex and gender passé? What do women artists want? What is the relationship of the body to language, to myth? Why are craft materials and craft techniques more or less still forbidden in the art world? What is an oeuvre? A signature style? What is the relationship of biography to photography? Who’s image am I? How can pain and fear be expressed in art? Grief?

Also, now that we know that a major influence on Smith has been Nancy Spero, when will we get the Spero survey we deserve? Can we look at Smith through Spero and Spero’s Artaud lenses? Dare we compare Smith to Beuys? Or is that like comparing hares and coyotes to wolves? And, in terms of materials, is glass the new fat?

A once-upon-a-time fan — at least I think he was such — attacked me at a party by saying that he liked reading me but that I was always solving problems he didn’t know he had.

Answer: And now you know you have them, so you had better start thinking.

* * *

Kiki Smith: Tale, 1992. Beeswax, microcrystaline wax, pigment, and papier-mache. Not at Whitney.

Birds Flying Around in Her House

A fellow art critic recently catalogued 34 materials used by Smith in the Whitney show, leaving out glass. How could he ignore glass? I counted 14 pieces made of glass. Invisible glass. Evil glass, I guess. The same writer, glorying in a not very funny paradox, calls Smith a major figure who makes minor art. Is her use of craft materials and methods what makes her minor? I also detect his usual loathing of the political. What else could calling Smith the “leading light of communally minded downtown avant-gardes” mean? Was there something wrong with being against the U.S. Nicaragua incursion or calling attention to AIDS?

One reason Smith is major is that she is fearless when it comes to materials, no matter how despised or humble. And, as the exhibition shows quite clearly, she employs beeswax, glass, clay, fabric and paper toward astoundingly expressive ends. If anyone thinks her work is just about material and form, then he needs his eyes examined. There are reasons for body parts and full-body casts, for representations of body fluids and eventually monsters, myths, and magical beasts.

Three of Smith’s most powerful nudes are not included in the survey at the Whitney — Pee Body, 1992; Untitled (Train), 1993; and Tale, 1992. The first two are made of wax and glass beads. In the first, yellow glass beads clearly represent urine; in the second red ones emerge as menstrual fluid. In her catalog essay “Unholy Postures: Kiki Smith and the Body,” art historian Linda Nochlin is particularly enamored, if that’s the right word, of Tale, which depicts another naked woman, but with a long tail of excrement coming out of the appropriate opening. It is a shame these sculptures were not included, but obviously there’s still enough indelicate material to discombobulate delicate souls. Even empty bottles labeled with the names of various body fluids —Untitled, 1987, originally shown at MoMA-are enough to disturb.

Some are also strangely offended, it appears, by Smith’s high visibility. She was indeed carried aloft as Art Goddess in Francis Alÿs’ 2002 art parade from Manhattan to Queens, when part of the MoMA permanent collection was temporarily moved. There is also no denying she is the daughter of Tony Smith, who, by the way, will be seen as one of the great sculptors of our time, along with his daughter.

Smith claims not to have been reacting against her father’s clean, clear, abstract, geometric sculptures — she and her sisters even helped with making the cardboard maquettes, a story everyone repeats — but instead was influenced by his devotion to art. Wouldn’t this unfamilial devotion be annoying to a child? Perhaps she protests too much. She didn’t start making art until he had passed on. The sons and daughters of famous fathers or mothers (I’ve known a few) have a hard go of it; don’t let anyone tell you otherwise. Any material or leg-up advantage is cancelled by the hard-act-to-follow syndrome or simply the normal need for approval.

Smith, who never went to Yale, or Rhode Island School of Design, or Columbia Teachers College, or any other art school, never felt the need for a proper studio and to this day blends living and working. And, of course, when required she works at foundries, residencies and workshops. You are not expected to pour your own bronze or blow your own glass. Sewing and drawing is possible at home, as it were, but other forms of making are more specialized, and you need furnaces and people with specialized skills. Minimalism made outsourcing a visible part of its aesthetic. Kiki inherits that, but gives it her own, handmade twist.

If nothing else, one of Kiki Smith’s great contributions to art culture is this fact: artists don’t need big clean studios. Perhaps we can bury that requirement once and for all. If you can’t imagine how an artwork will look in a gallery without an ersatz gallery to see it in, then you shouldn’t be looking at art. Too often, dealers, curator, and collectors require the perfect white-walled studio, or they do not take the artist seriously — even though all it means is a mommy or daddy who can come up with the bucks.

I remember an artist whose work I had followed for years telling me a horror story. He came from a poor background and liked working in a modest, cluttered apartment. In fact, his apartment on the Lower East Side was part of his art. He was able to move to a bigger place in Hell’s Kitchen (now called Clinton), but soon it was merely a double-size version of his tinsel-strewn downtown digs. Once, an extremely famous and well-connected curator from Europe paid a visit. He took one look at my friend’s amazing workplace and, proclaiming “I cannot look at art in a place like this, you are not a serious artist,” marched right out the door.

Alice Neel painted in her living room. So did Hopper.

Kiki Smith, I am told, has birds flying around inside her house.

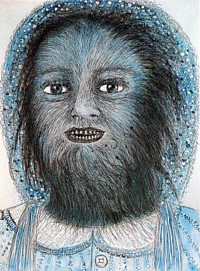

Kiki Smith: Wolf Girl, 1994. Etching

She Is Our Shaman

As an art-world personage, Smith is indeed strange and dreamy, with her mane of silver hair; but her art is deeper than fashion. What other artist do we know who, since Joseph Beuys, has attempted so much? She is our shaman.

A naked woman stepping out of the body of a dead wolf, as in Rapture of 2001? A hirsute Little Red Riding Hood as in Daughter of 1999? This is not the kind of art you can dismiss as bad form. It is not about formal values. Cross-culturally, shamans get their bodies cut up and they are reborn with a suitable animal guide. Smith has moved from body parts, to whole bodies, to saints and wolves.

Kiki Smith: Rapture, 2001. Bronze

FOR AN AUTOMATIC E-MAIL ARTOPIA ALERT WHEN A NEW ESSAY IS POSTED CONTACT; PERREAULT@AOL.COM