Things You Wish You Had Never Found Out

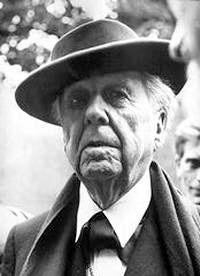

Is a masterpiece still a masterpiece once you have discovered that the architect of record was notoriously, dangerously lacking in engineering skills? That the architect wore elevator shoes? That he was a hypocrite about homosexuality?

Frank Lloyd Wright was antigay when it came to what he called that “Pansy Patch of the Museum of Foreign Art,” as exemplified by Philip Johnson and Henry-Russell Hitchcock at MoMA, but covertly allowed his majestic, Russian-born wife to initiate homo-hookups among his Fellowship Boys to keep them from bouncing the local dairy maids. Also, though he also favored gay men as staff leaders, in the ’50s he held an antihomosexuality “show trial” of his most trusted helper.

A new tome spills the beans about Mr. Wrong: The Fellowship, The Untold Story of Frank Lloyd Wright & the Taliesin Fellowship by Roger Friedland and Harold Zellman (Regan). Enormously detailed, this is a book for anyone interested in modern architecture, cults and esoterica, gay history, and the psychology of the artist as savior. And although the authors do not theorize or editorialize — a lack of theory is the only fault — they are unflinching in their methodical, mostly chronological exposure. Read it and weep. Not only are there walk-ons by Nicholas Ray and Anthony Quinn (both briefly Fellows), but also appearances by Charles Laughton, Marilyn Monroe, and Joseph Stalin’s daughter.

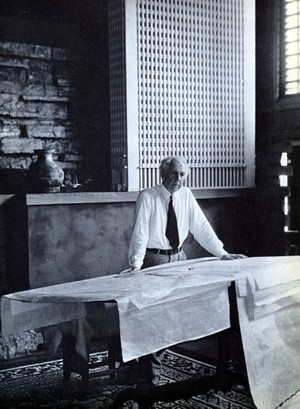

Friedland is a professor of religious studies and sociology with an interest in “the intesections between culture, religion, and eroticism,” all of which come into play in what is a long-needed tabulation of Wright’s failings. Zellmanis an historian of modern architecture and communitarian movements, as well as a practicing architect. It is because of the last that we gain fresh insights into Wright’s reliance upon on-site improvisation and dependence on construction workers to fill the dangerous gaps in his architectural plans.

Based upon an enormous amount of research, The Fellowship is not so much a revisionist view of Wright — the value of his architecture, aside from the master’s lack of engineering skills, is here apparently incontestable — but a new biographical context that factors in a hidden history of the esoteric and the sexual. And although monsters are always interesting, if this were a movie, you wouldn’t believe it.

And is his architecture incontestable?

Getting It Wright

According to Friedland and Zellman in their straightforward investigation, Wright’s Fellows could not define what the Masterbuilder meant by Organic Architecture. They were actually not taught very much, but used as free labor. Being within his magnificent presence was considered enough to create art by absorption. I take Organic Architecture to be building from the inside out, starting from living space (useful or not); truth to humble materials; and adjustment to the site. And not form follows function, but the identity of form and function.

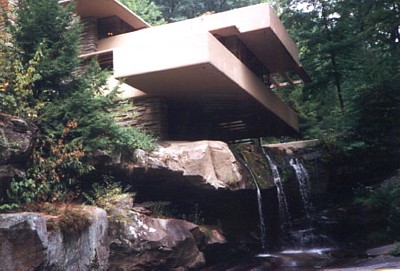

These principles he mostly faked. Architecture, like so much else, is written by photography. It if doesn’t make a pretty picture, a building doesn’t exist. Placing a house directly over a very loud waterfall is stupid, as in Fallingwater, but it makes for good photos.

Emphasizing the horizontal for houses in the prairie and the desert makes some sense. But what sense is there in getting rid of roof gutters? Unless you know that the spiral structure of the Guggenheim Museum in New York City was meant to please Hilla Rebay, the Theosophist in charge, that fine shape makes no sense at all, particularly in regard to the surrounding environment. Looking at paintings while walking up a six-story spiral ramp is stupid.

We are used to the Guggenheim now, where, oddly enough, representational paintings look better on the curved walls above the slanting floors than do the non-objective paintings that the founding curator preferred. Wright, always against painting, wanted the art on the floor, leaning against the walls — or, as he said about his houses, no art at all. His architecture was the art. Truth to materials? Honest structure? Forget about it. The Guggenheim is made mostly of Gunite; the same stuff they still use for swimming pools. And the various levels of the ramp are not actually cantilevered.

Wright’s biggest playing field was domestic architecture, and late in his career he tried to launch his populist, affordable Usonian house. I was once thrilled to visit curator Ellen Johnson’s restored Usonian house in Oberlin, Ohio. And I have seen Wright’sUsonian house in Staten Island, but was not impressed. Wright did innovate the open plan, but he was probably better at housing for the wealthy than for the middle class. I did attend a conference at Wright’s 1937 Wingspread outside of Racine. The central living space is like a giant teepee, and the hallways and the Johnson family bedrooms all have extremely low ceilings. Why? To increase the drama of arriving in the giant living room, or because the Masterbuilder was (he claimed) five-feet-eight-and-a-half inches tall?

Is that with or without elevator shoes?

And his furniture! He preferred built-ins and hated when clients brought their junk into his houses. The chairs he did make are uncomfortable. I have sat on some. In his Autobiography he admits that he had many black-and-blue marks from sitting in his own furniture.

When Gurus Collide

The news set forth in The Fellowship is the unexpectd role of the Fellowship or apprenticeship system in Wright’s later career and, through wife Olivanna, the interplay with the esoteric. Strapped for cash during the Great Depression and his innovative buildings apparently all behind him, Wright borrowed the idea of taking on “fellows” for a fee. Working for Wright cost more than the tuition for an architectural degree. He got the idea from Dutch acolyte Hendricus Wijdeveld, with a good helping of Arts and Crafts rhetoric from Charles Ashbee (founder of the important British Handicraft Guild) and Elbert Hubbard, who created the Arts and Crafts Roycroft colony in Aurora, New York. If you read Wright’s Autobiography you will smell the inflated pomp of Hubbard’s bombastic lecture and essay style. At first Wright copied Hubbard’s long hair and style of dressing. Hubbard himself was mimicking Oscar Wilde.

We did not know that Wright’s beloved mentor Louis Sullivan was probably gay. We did already know that early on, Wright faced scandal (he abandoned his family and ran away with the wealthy Mamah Cheny) and tragedy. Mamah and her two children were killed by a crazed servant who nailed Taliesin shut except for the bottom half of a Dutch door, set fire to the house, then axed each victim when he or she crawled through the opening.

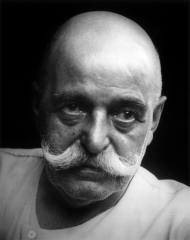

And we knew that the illustrious wife who followed — Olgivanna Hinzenberg — was a major disciple of Georgi Ivanovich Gurdjieff, the 20th century magus.

Gurdjieff claimed to be the repository of certain secret traditions and spiritual techniques, convincing a wide range of culturati from Margaret Anderson and Jane Heap (editors of The Little Review, where Joyce’s Ulysses first appeared in the U.S) to Lincoln Kirstein of the New York City Ballet. Although L. Ron Hubbard, founder of Scientology started as a science fiction writer, Gurdjieff ended as one: Beelzebub’s Tales to His Grandson is unreadable unless you realize that like the Zohar or some Sufi texts, it is the reading of the text that works on more than the meanings.

But I didn’t know that Gurdjieff and Wright, who didn’t exactly hit it off,b met more than once;b that Wright’s wife Olgivanna struggled to make Taliesin West a Gurdjieff Center.b The Fellowship Boys were instructed in Gurdjieff’s spiritual dance-system and public performances were given at Taliesin. bAt the end — Mr. Wrong, dead — the handsome Olgivanna won her battle,b but by then she had not only inappropriately assumed her husband’s architectural mantle, but decided she could supercede G.’s teaching with her own brand of spiritual work.

Olgivanna certainly did not have her husband’s aesthetic sense. I saw Taliesin West before it had been restored and cleared of her kitschy amendments. Not good. And although I did not then really know how far the Wright Cult and the post-Gurdjieff Cult had progressed, I thought the guided tour weird, the apostles zombie-like.

By most accounts, Olgivanna never had G’s inner light. She could replicate the encoded dances, but she could not read minds, cause orgasms and erections by remote, and certainly, for all her meddling and match-making, was not known to be able to startle disciples into higher consciousness — or create a soul by an insult, a look, or the assignment of meaningless work. The imposition of intentional suffering, however, she seemed to know too much about. Yet we in Artopia (since Artopia is not Utopia, and certainly not Usonia) surely understand that the soul is not so easily confirmed, nor does spiritual progress, to put a fine theological point on it, necessarily reveal itself immediately.

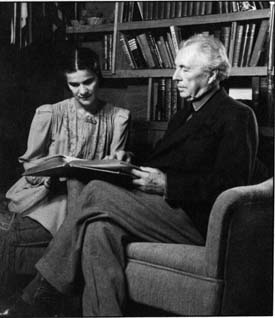

Mr. and Mrs. Wright

Frank Lloyd Reich

Although Wright could charm when necessary, Friedland and Zellman make it clear, through the extensive use of interviews and the Wright Archives themselves, that the Great Man was wildly self-centered, monomaniacal, incredibly vain, and abusive to his wives, his step-daughter, his daughter. And paranoid? Was Phillip Johnson really out to get Wright? Johnson had attempted to form an American Nazi Party, proclaiming that the Third Reich was the future of architecture. Mies van der Rohe, whom Johnson championed and Wright despised, had been, we now know, a Nazi collaborator, no doubt trying to save the Bauhaus, but a collaborator nonetheless.

Like Henry Ford, another great American, Wright thought that Hitler was on to something good. If London were leveled, a British branch of Wright’s “visionary” Broadacre City could easily be built. You would have thought Johnson and Wright would have had a common cause.

Yet there is no explaining it. Later Wright was constantly under Hoover-watch as a Soviet symp. He had made pro-Soviet statements even after Stalin’s Moscow Trials. His dream was to have Usonia, composed of Wright-controlled Broadacre Cities, secede from the Union, leaving New York and Chicago to the wolves. Or did he mean Jews?

Wright’s beliefs seemed to be centered around America First Fascism; he belonged to the American First Committee, advised his Fellows to refuse to be drafted during the Second World War, and he counted among his friend Charles Lindbergh, a political hero and would-be American savior. Yes, Lindbergh — who accepted a metal and a sword from Goering and, in an infamous speech in Des Moines, Iowa, in 1941 , said: “Their greatest danger lies in [the Jews’] large ownership and influence in our motion pictures, our press, our radio, and our government. We cannot blame them for looking out for what they believe to be their interests, but we also must look out for ours.”

Although Wright had many Jewish patrons and allowed some Jewish apprentices (when they were rich enough, he could get his hands on their money), he was clearly an anti-Semite.

Wright was the great man, the greatest architect in the universe, the fountainhead that inspired Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead. Although when that author, a dangerous right-wing nut-case herself, finally met him, she thought he was insecure and dishonest and was appalled that the Fellows ate lesser food than Mr. and Mrs. Wright and their guest. The Fountainhead movie which I saw by accident last week on Turner Classic Movies put the radiant Patricia Neal and the ruggedly handsome and tall Gary Cooper to evil use. King Vidor’s direction and the Steiner music are perfect. It is the ideology that is ludicrous and, like Wright’s ideology, dangerous.

Our authors, Friedland and Zellman, do allow that Wright was bipolar. Is that an excuse? Hitler was probably bipolar too. Does being a 19th-century midwesterner excuse Wright’s isolationist, antisemitic, antiurban world view? I don’t think so. I cannot look at any of his buildings now without thinking of egotism and hate.

Of course, International Style modernist architecture ironically would not exist without the early influence of maverick Wright, but that establishment-approved style, according to Our Hero, turned out to be soulless, thoroughly homosexual, and anti-American. Those pansies at MoMA again!

In short, Mr. Wright was Mr. Wrong. We are not amused by his duplicity, loan-scoffing, tax-cheating, and the bullying and brow-beating of all within his kingdom. He got on any ship that was leaving port, followed any scent in the wind as long as it helped his career. I suppose he might have said — like one-time Nazi party member, soprano Elisabeth Schwarzkopf — “I only lived for art.”

FOR E-MAIL NOTICE OF ARTOPIA ENTRIES AS THEY ARE POSTED WRITE PERREAULT@AOL.COM