John Perreault: View from Hilton Hotel Window, Houston, Texas, 2006

Against Nostalgia

At the American Craft Council’s “Leadership Conference” in Houston, the issues were the same, the people friendly. On a side trip, my travel buddy was cured of his nostalgia for San Antonio.

We were attending the ACC Conference for different reasons. My friend was on a panel; I was on a mission. Perhaps I could find a few more writing or curatorial gigs. Hey, just when you thought it was safe to go to a craft event, I’m back.

Why should anyone in the art world be interested in the craft world and its problems? Because, like it or not, the craft world is part of the art world. Take a look. Here and there, there are artists with craft roots showing in art world galleries: Betty Woodman (Protetch), Ken Price (Matthew Marks), Dale Chihuly (Marlborough), Josiah McElheney (Andrea Rosen) As in the ’80s, there are art world artists appropriating craft world media and techniques: Kiki Smith, Charles LeDray, etc.

Plus there is the great language problem, which is more than taxonomy. Language is philosophy. You cannot compare apples to fruit, but only apples to pears. Craft is a subdivision of Art. Economics, gender, class, use, and geography play roles, too.

Also, I wanted to see if the craft world was as bad — or as good — as I remembered. I’m talking of high-end, handmade art that converges with painting and sculpture and is no better or worse than either — at least in theory. My theory.

I had to conquer my nostalgia, too, having been a participant in the craft world for, I had grown to think, too many years, beginning way back when the feminist appropriation of craft forms stimulated my interest. Basically, if Joyce Kozloff’s paintings of tiles and Judy Chicago’s Dinner Party plates and needlework runners were curiously provocative and satisfying, why not go to the sources? And the more I read (or remembered), the more I liked the politics and the idealism of crafts.

* * *

The Webb Site

So what is the American Craft Council, and why does it have to have a Leadership Conference?

The American Craft Council (ACC) has a certain history. You can look it up. But basically it descends from Aileen Webb’s project. Mrs. Webb — in the craft world she was and is always called Mrs. Webb — had the idea that the crafts needed some help. Like William Morris, so many generations before in Great Britain, she feared that craft was in jeopardy and its media and making-traditions would be lost to mechanization. And like the philanthropic ladies who founded the craft projects in the inner cities and Appalachia earlier in the 20th century, she may also have felt the need to shore up Anglo-Nordic traditions.

Mrs. Webb was friendly with the Rockefellers and the Roosevelts. Herself well-healed and philanthropic, she started the School for American Craftsmen upstate and then a shop in New York City that became the Museum of Contemporary Craft, which became the American Craft Museum. The ACC was the umbrella organization that grew to include Craft Horizons, which became American Craft Magazine, and a national family of craft fairs providing a market for handmade, useful art.

Now, of course, the American Craft Museum is totally independent of the ACC and has recently changed its name to the Museum of the Arts and Design. We also hear that craft-fair profits are flat. Membership of the ACC has changed from primarily artists to a spectrum of interested parties that includes dealers, curators, collectors. Most of the artists at the conference, I suspect, were blessed with teaching jobs and no longer depended on sales at craft fairs — or galleries, for that matter.

The ACC is clearly in transition and perhaps in the thrall of an identity crisis. Does anyone care about craft? Do the artists still need the ACC and its projects? One symptom is that this was the first ACC conference in 20 years. A deadly lapse for an artists’ organization, right?

* * *

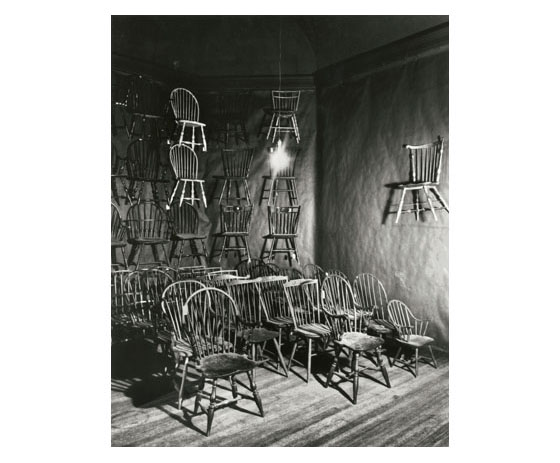

Andy Warhol, Raid the Icebox (detail), 1970

Parlay-Vous (an Aside, Sort of)

We arrived in Texas a few days prior to Conference Registration and then took off through driving rain for San Antonio, acting on the Parlay Principle of business travel that I learned from the late art critic and editor Gregory Battcock. Battcock and I, along with many others, were in 1970 the guests of collectors Dominique and John de Menil. Their daughter Christophe would later be the co-founder of the Dia Foundation, and Dominique herself would create the Menil Collection, a Houston Museum of some note.

The de Menils had sponsored an Andy Warhol exhibition at Rice University in Houston. It was called “Raid the Icebox with Andy Warhol,” and Warhol merely selected stuff from the Rhode Island School of Design collection: a wall of chairs, hats and hatboxes, and so forth. It was clever indeed, since it represented art as curating or curating as art. But my pal Gregory, who loved to travel, parlayed his return trip to include a stop in Puerto Rico. (This is sometimes called triangulation.) He somehow commandeered a de Menil limo and had it driven onto the runway to stop the plane he needed. The Parlay Principle: if you are somewhere, use that occasion to go somewhere else.

Here is my most successful use of the Parlay Principle:

My first trip to Australia required a fueling stop at Fiji. We got out of the plane, traversed an odoriferous zone of tropical flowers, then through a gift shop (where I bought a pareu made in Malaysia) and back to the waiting room before we got on the jet. The aroma of those nocturnal tropical flowers lingered.

A few years later, I needed to go to a conference in Wagga-Wagga, which is in Australia. I thought: maybe I can stop in Fiji. I called my travel agent, Dui. It will only cost a hundred dollars extra, he said, and I know a great hotel for $75 a night. But I have another idea. One of the Qantas flights stops at Tahiti and then goes on to New Zealand before landing in Sydney.

Thus a simple flight to Australia for business became a South Pacific tour, using Perreault’s Parlay Principle. New York to L.A. — stopping overnight to see some friends — then on to Honolulu; next day to Tahiti; then a gigantic catamaran to Tahiti’s sister island of Moorea. A few days later landed in Auckland, where you could bungee-jump down the side of a 20-floor bank building for a fee. Rotorua: male Maori dances with great tattoos and an outdoor Victorian mineral bath, with a grid of temperatures and mineral contents. Napier, an art deco seaside resort constructed after a devastating mid-1930s earthquake. Sydney, Wagga. And, of yes, on the way back, Fiji with Hindu temples in sugarcane fields.

The Texas Taco Tour was simple by comparison.

* * *

San Antonio, My San Antonio

In San Antonio, I was cured of tacos. I prefer the authentic Mexican pulled-pork, green-sauce soft tacos I get in the East Village. Tex-Mex is the “Mexican” food we know too well with everything topped by everything else in a mushy pile, even in San Antonio. However, I hasten to add, the scrambled eggs and crunchy tortilla strips at the Blanco Cafe made San Antonio totally worthwhile. Should I really begin to use lard for my scrambled eggs? Better not.

And we stayed in the 1909 Bullis House mansion, a B & B next to Fort Sam Houston. General John Lapham Bullis, a Civil War veteran, had been the Fort paymaster. Fort Sam Houston is where Apache Chief Geronimo was held. Bullis had something to do with his capture and so Geronimo’s ghost haunts Bullis House, apparently taking the form of a whiff of cat perfume. And, oh yes, the Fort across the street was a Japanese and German internment camp during World War II.

Tacked to the oaken front desk of the empty B & B was an e-mail printout I was tempted to steal, but thought I had better not since it did contain a dire alert. The writer was warning all women to beware of shady perfume salesmen in parking lots. They approach, offering brand-name bargains, and when you sniff the sample it turns out to be chloroform; you awake to find your purse, watch and jewelry gone.

We had dinner out with my buddy’s old girlfriend’s charming mom, and I had a taco sampler: hard, soft, and puffed, the latter a San Antonio specialty that in this incarnation resembled a soggy sponge.

I had been to San Antonio before, perhaps 20 years ago. Had I passed my future friend on his bicycle or driving his Camaro on his way to a radio station or a film-shoot? I remembered the WPA River Walk. You don’t know it’s there, snaking below street level through the empty downtown. But when I peeked over a railing there were no floating restaurants or tourist barges plying their way, as remembered, and the walks were as neutron-bomb empty as the streets above. Everyone was at the mall and I guess it wasn’t tourist season. And, of course, I remembered the Alamo.

We did look up Matthew Drutt, formerly of the Menil Collection in Houston, now the new director of Artpace. Matthew’s wife and my friend’s bride-to-be had worked together on the staff of a major New York museum. Artpace, sponsored by a hot-sauce heiress, houses three or four resident artists at a time, and then their studios become the exhibition spaces. We got a peak at three installations in progress: Allison Smith’s wooden horse for a Civil War reenactment; Katie Pell’s “flaming” kitchen stove, and Chiho Aoshima’s watercolor mural of the San Antonio skyline replete with manga eyes.

The building is a sleek conversion of a former Hudson dealership, and could easily be expanded to become the contemporary art museum that San Antonio sorely needs.

Then off to Austin to see the Ex-Girlfriend.

* * *

Lockhart Courthouse, Lockhart, Texas

Where’s the Beef?

I insisted, with no resistance from my traveling companion, that we stop at Kreuz Market in tiny Lockhart for what everyone agrees is the best German-style barbecue in the universe, cooked over live-oak logs, sliced before your eyes and served on butcher paper with not a knife or fork in sight. You don’t need them.

Lockport is basically an ornate courthouse surrounded by a necklace of buildings one-block deep, in the middle of the scary flat expanses of Texas. Where, one wondered, is the James Dean of Giant? Lockhart is one of the German settlements in Texas. But Kreuz Market was no longer hidden behind an unmarked door. We found it by the smell of smoke and meat. It had gone up-market and moved to the edge of Lockhart to accommodate the tourist buses, across the street from the town cemetery

Given the iffy nature of beef, no matter how tender, smoky, and emphatically sauceless, it is not a reassuring sight to spy the rather expansive cemetery, as, stuffed with melt-in-your-mouth brisket and salty sausage, you roll back to your rented car. As everyone says, pickles here count as vegetables. But you could, as I did, have added a healthy portion of German potato salad made with vinegar, bacon bits, and rendered bacon fat.

Brisket, sausages and white bread on butcher paper.

But was the beef as good as remembered? It can’t be the same, but perhaps memory is to blame. The meat is no longer surrounded with enough smoke and cowboys. And — here’s the rub, or more correctly, the lack of rub — you can go online and have it shipped. Get the brisket. And although no sauce is still available or required, I learned online that the German potato salad was added not long ago, in 1999.

* * *

Coffee Bar on Austin’s Hippie Strip

Austin City Limits

In Austin, craft reappeared. The Ex-Girlfriend, who had been in several Austin-based films and a casting director too, was now a mom, writing scenarios. She had wed a blacksmith. My great-grandfather on the Gautier side was a blacksmith, so I was particularly interested. We visited the co-op studios, where a painter and a talented furniture-maker also held forth, and then to a stone-carver/sculptor who showed us a prize collection of Mayan chisels. The ceramicist wife who did traditional Japanese inlay was friendly, too.

Our Austin digs, inexplicably called the Hotel San Jose, was a converted motel on the old hippie strip. It features Dia-like, Chelsea-like sealed concrete floors and Eiffel chairs, and i-Pod stations. The Ex-Girlfriend, accustomed to putting up players from Hollywood, had recommended this coolissimo place.

Then off to Houston, to the Hilton — which displayed a strangely overlooked Dale Chihuly chandelier in its lobby — to contemplate the Craft Crisis. I had already learned on this trip that I can have nostalgia for a past I never had — my friend’s. Furthermore, not only is it true, as Thomas Wolfe wrote, that you can’t go home again, you can’t relive the perfect Texas brisket. Now I needed to prove that I could be cured of a nostalgia for the future — a past invented by William Morris.

* * *

Panelists (projected) and Audience, 2006

Notes ona Conference

1. Andrew Wagner, formerly of Dwell, is introduced as the new editor of American Craft Magazine. After 30 years, Lois Moran is retiring.

2. Sculptor Martin Puryear gives the keynote speech. Beforehand, he wonders why he had been asked, but, always a charmer, he handles his assignment well. Did not show one slide of his own work, which may have left some in the audience totally in the dark about why indeed he had been asked. Certainly not just because he has a show coming up at MoMA or, as he confesses, has a guilty hobby of making traditional furniture for his own use. Clearly he has a particular liking for wood and for handwork. Was he invited because he is not afraid to use the word “craft”?

3. Houston Museum of Fine Arts director Peter Marzio offers a lively exposition of the history of the fine arts versus craft in Houston and tells us why craft has become a part of the museum’s program. One wishes for similar local histories to flesh out and complicate the subject, which is far too often generalized.

4. Texas-style sauced BBQ and two-step and line-dancing (not by me) at the Houston Center for Contemporary Craft, where sculptor James Surls’ excellent exhibition “Finding Balance: Reconciling the Masculine/Feminine in Contemporary Art and Culture” holds forth.

Charmaine Locke, (detail) Painting.

It breaks some rules. Surls himself has work in the show, as does his wife, Charmaine Locke. Plus there’s work of two former directors of the Anderson Ranch, at Snowmass, Colorado, where Surls sometimes teaches. (Full disclosure requires me to note that I have taught there, too.)

In the catalogue there’s a kind of summary of Leonard Shlain’spopularizing “Sex, Time, and Power: How Women’s Sexuality Shaped Human Evolution” by the author himself. Here, since the exhibition is about the relationship between men and women, he omits his gay chapter, wherein one may learn that gay men have a 15% larger corpus callosum than everyone else. The corpus callosum connects left and right hemispheres of the brain, thus suggesting easier traffic between the opposing lobes and less specialization, perhaps explaining the proposed greater creativity of gay men.

And yet the art is on the whole exceptional, the theme (or themes) explored in a complicated way, and the pauses-for-thought unavoidable. Surls was motivated by two factors: he not only has a wife, he is the father of seven daughters, and an Internet search with one of them revealed that most women’s organizations worldwide exist mostly toprotect women from men. I say break more rules and certainly let more artists like Surls curate exhibitions. Surls is a shamanistic sculptor who most typically works with found wood in the form of branches and trees and is not usually thought of as a craftsperson. Perhaps it takes a craft venue like the Houston Center to force art out of its rule-abiding box.

5. Glenn Adamson (of the Victoria and Albert) and Edward Cooke (of Yale) use their discussion to announce their new peer-review periodical, The Journal of Modern Craft, forthcoming in 2008 out of Great Britain. Can they rewrite craft history by reexamining what has already been written, but is not acknowledged? Can a peer-review periodical offering academic points to contributors rise above the conformist and the mundane? We certainly hope so.

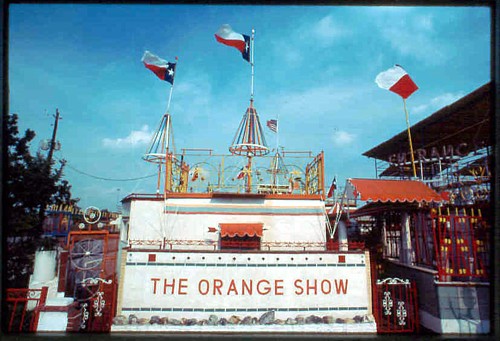

6. My friend had a great idea. We played hooky late one afternoon to tour some Houston Outsider Art treasures: Cleveland Turner’s Flower Man House, Jefferson Davis McKissack’s The Orange Show, John Milovisch’s Beer Can House and the Art Car Museum. Craft may overlap sculpture, but no one ever points out the craft used in Outsider Art. The spectacular Orange Show, for instance, required woodworking, tiling, metalwork. Is this blind spot because of the Craft World’s fear of Folk Art — although Folk and Outsider are very different — or because craft, to be Craft, now must be schooled?

7. David McFadden, the bright chief curator of the Museum of the Arts and Design, reveals that institution’s opening exhibition in its controversial new site, the former Edward Darrel Stone Gallery of Modern Art at Columbus Circle. The opener will be called “Making It: Materials, Process, Meaning.” His point seems to be to avoid both the words “craft” and “design.” Although some design objects show up in the slides, most of the objects are craft. So maybe a rose with no name is still a rose.

8. Curator Timothy Anglin Burgard of the Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco shows us how he has successfully integrated selected craft objects from their Sachs Collection into their fine-arts array.

9. Curator James Elaine of the Hammer Museum in L.A is puzzled, like Puryear, by his invitation to speak. The mystery is solved when he shows slides of his award-winning 2005 exhibition, “Thing.” Many of the works use craft materials and techniques. By the way, Kristin Morgan’s unfired clay, life-size automobile (from “Thing”) is, next to works by Josiah McElheney, the most-shown image at the conference. What does this prove?

10. Brett Littman’s panel seemed to upset a few people because of a handout called “New Paradigms in Curating Craft and Design: A Manifesto.” Littman, that firebrand, is deputy director of P.S. 1 and a self-identified crafts patsy, having worked with me at UrbanGlass in Brooklyn. At this point he has also curated a number of craft and design exhibitions, most notoriously “Civic Matters,” a Swedish-American continuous collaboration with no end or end-product. During the Q & A, my anonymous contribution to “The Manifesto” was publicly singled out by one university jeweler as being particularly outrageous: “Change the name of the Museum of Modern Art to the Museum of Modern Art, Craft and Design.” Irony, alas, will always fail. (And I had always liked her work!) Perhaps, as now seems to be the fashion, the ACC should also drop “craft” from its name and begin calling itself the American Arts Council. This would please a lot of collectors and, alas, craft artists too.

* * *

The conference, however, can best be judged by what it did not include: no discussion of whether the ACC mission is still valid, no discussion of the use of computers in craft-making, no discussion of the Internet as a salesroom for craft, no discussion of the bland ACC Website, no discussion of how the public can be educated to embrace craft values, no discussion of how to improve the taste level of the craft fairs that give craft such a bad name.

If the ACC mission is to educate, then the mission is in trouble.

If the mission should be to encourage and preserve handmade art that uses traditional craft forms, techniques and materials, then one might wonder if craft-media groups such as G.A.S., S.N.A.G., N.C.E.C.A. are already doing that, plus providing peer-to-peer forums, pep rallies, and technical and career information.

American Craft Magazine is still important because of the possibility of cross-referencing among ceramists, glassworkers, woodworkers, weavers, metalsmiths and the promotion of a common cause. More cross-disciplinary conferences are needed. Twenty years was too long to wait. But why not hold a conference of representatives from all the media groups?

On the other hand, perhaps the American Craft Movement is over. It has been around for over 80 years. Did Cubism or Surrealism or Abstract Expressionism last that long?

Answer: Craft is not an art movement. Craft is a belief system, like art itself.

To receive Automatic Artopia Alerts when new entries are posted: contact perreault@aol.com.