Andy Warhol Bridge, Pittsburgh, Penna.

The Allegheny Allegory or the Rule of Three

Three things brought me to Pittsburgh, the city of three rivers. I missed the opening of the Andy Warhol Museum in 1994. My previous visit, as a juror for the Three Rivers Arts Festival, was long before that, and now I was also seduced by the possibility of seeing in person the contents of one of the Warhol Time Capsules. As an NEA panelist in the deep-dark past, I voted for Mattress Factory funding, but I never visited this pioneer alternative space, now a museum and in its 25th year.

The third lure requires some explanation. As a child I once adopted six stray dogs, much to my father’s chagrin. Presently I have no animal companions because I empathize with them too much. Cities are cruel. Would I go for four square meals in trade for an apartment prison and having to hold off my bodily functions to the beginning and the end of the day? Would I want to give up chasing squirrels?

If sentiment were not enough, who now can repress the effects of global warming upon our animal co-tenants? It’s unlikely that polar bears and mockingbirds will have the wherewithal to escape to other planets like us. “Fierce Friends: Artists and Animals, 1750-1900,” to August 26, 2006 at the Carnegie Museum of Art therefore seemed of some import.

To accomplish this three-fold mission, I signed on for a press tour offered by Visit Pittsburgh (until recently called the Pittsburgh Chamber of Commerce and Visitors Bureau). As luck would have it, in keeping with the triple-header theme, I was also able to see the identical, bright yellow Three Sister Bridges across from my hotel. The central bridge is actually named for Andy Warhol. Is there another bridge in the whole world named for an artist?

More unfinished business: We took a ride one evening on the Duquesne Avenue funicular, one of two that still climb the bluff overlooking the Monongahela River. Here they are called inclines, a Pittsburgher opined, because the locals cannot pronounce “funicular.” There once were 20 or so, but the two that remain are used only for commuters and not for horses, coal and feed.

The shoebox (actually more like half a shoebox) juts out parallel to the riverbed and is attached to rails at the backend. Balanced by a descending car — this is the ancient funicular trick — we are hauled by cable up the bluff to a spectacular view. A Visit Pittsburgh representative claimed this view was designated by USA Today Weekend Magazine as the Second Best View in America. We looked down on the glittering V that is downtown Pittsburgh; the Three Rivers Fountain at the tip, inGolden Triangle Park, was gushing too. But more than one of the writers in our group wanted to know what the First Best View in America was. The publicist had forgotten. The Golden Gate from Pacific Heights? The Big Apple from the top of the Empire State Building or coming in on a jet? Her lips were conveniently sealed.

* * *

Sometimes I wish the world would more neatly conform to numerical schemes. But it doesn’t. An art pilgrimage to Pittsburgh should have more than three stations. There are indeed three identical bridges over the Allegheny River, as befitting a Catholic and therefore trinitarian city, but the Three Rivers idea is a bit more complicated. Actually the Allegheny and the Monongahela converge here to become the Ohio River, to form a peace sign and not a chicken foot. To complicate matters even further, I am told there is a fourth river, unnamed and invisible. This Fourth River (as it is always called) provides the water for the Golden Triangle fountain, and further upstream assists in cooling the Convention Center, now the second-largest “green building” in the world.

In the interest of obscurity and in conformity tomy principle of adding at least one strange item to my Artopia texts so no one will think they’re reading the N.Y. Times or any of the big art magazines: Three is not Three; Three is Two (Two becoming One); Two is Three (adding the underground river); Three (becoming the Ohio) is Four.

* * *

We also visited five private collections, one of which was corporate.The best featured an impressive collection of Palissy Revival ceramics in a Modernist house to die for. But we all also marveled at the private digs of Barbara Luderowski, director of the Mattress Factory and curator Michael Olijnyk. Luderowski, in her half of the top-floor loft, displays her toys, dolls, and oddities in huge glass cases; Oliknyk, in his half, displays primo examples of Mid-century Modern: Eames, Russel Wright, and a wall of sunburst clocks.

But never fear,if you make the Pittsburgh Art Pilgrimage, there is a lot of public art to see. We had a walking tour of art downtown: Jenny Holzer’s LED piece on the roof terrace of the Rafael Vinoly Convention Center was the outstanding offering. The texts are from novels that take place in Pittsburgh.

Jenny Holzer: For Pittsburgh

While you are in the bustling downtown area, you should also drop in on the Wood Street Galleries, a nonprofit art space specializing in Media Art. They were between shows. Artist Michael Oliveris was in the middle of installing his Ultraviolet Acquiesence and Deep Space Drip Culture installation, but we were given a catalog of past exhibitions and their offerings seem entirely worth a gamble when nearby….. Later we were carted to Carnegie-Mellon University, the alma mater of both Warhol and Philip Pearlstein, for fine outdoor works by Jonathan Borofsky (a version of Walking to the Sky) and Mel Bochner and Michael Van Valkenburgh’s Kraus Campo, a garden/sculpture.

Jonathan Borofsky: Walking to the Sky

Mel Bochner and Michael Van Valkenburgh: Kraus Campo

The Holy Warhola Shrine

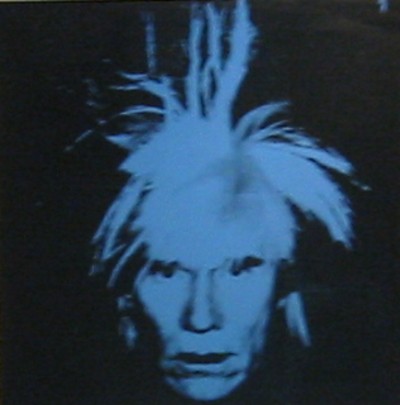

Andy Warhol: Self-Portrait, 1986

Andy Warhol (born Warhola in 1928) hated Pittsburgh. Pittsburgh then was not Pittsburgh now, currently a culture capitol worth visiting. Since Warhol’s middle name might have been Perversity, it is only fitting that the Warhol Museum is where it is, a glory to the once-and-famous city of steel mills, plate glass, aluminum and anthracite. Of course, there is only one steel mill working now. Plate glass is represented by Philip Johnson’s weird glass-faced gothic skyscraper.

And we read last week that Alcoa is an example of the new trend of relocating corporation headquarters to the Big Apple. Aglitzy Alcoa Building still exists in downtown Pittsburgh with 9,000 employees, some of whom may have been surprised that the stealth headquarters of Alcoa has been Manhattan for some years now. If you were a CEO or even a CFO, wouldn’t you rather be where all the big boys are, wheeling and dealing?

So why is the Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh? Surely not just because Andy suffered through art classes at Carnegie-Mellon University. According to Warhol Museum director Tom Sokolowski, unlike Gotham museums, the Carnegie Museums agreed to the Warhol Foundation’s terms: take all the art works in the estate and create a separate gallery or building. New York museums wanted to cherry-pick ,and a free-standing or even an attached Chapel of the Holy Warhola was obviously out of the question.

The Warhol Museum (one of four Carnegie Museums) was retrofitted by the same folks who gave us Dia Chelsea and Dia Beacon. It’s an old Frick factory. Seven chic, stripped-down industrial stories, with the requisite exposed cement floors, are located directly in line with the Andy Warhol Bridge.

Oh, Andy, all your sins are forgiven!

Although he was one of the smartest artists I have ever met, late in his career I was displeased with his society paintings. For $40K, if I remember correctly, any schmuck or schmuckess could sit for a Polaroid and get a Warhol portrait over their fireplace.Some said it was the evil influence of his associate Fred Hughes, or that Andy just needed more and more money to make movies. In any case, I still hold that the “portraits” work best when they are pop-culture icons. Who really cares about collectors Ethel Scull or Lita Hornick? Lita published one of my book of poems under her Kulchur imprint, so of course she is of historic interest. But I don’t think my nephew would recognize her face, whereas I am sure he would recognize Marilyn, Liz , Jackie, or Elvis. Those are faces that linger, that are like the images of saints in the Catholic Church. Like each of these, Andy too is known on a first-name basis. Mickey Mouse is more famous than Donald Duck because he can be called Mickey alone. Judy is Judy Garland and never Judy Canova.

Fighting the urge to visit the gift shop first — an EmpireT-shirt for my beloved would have to wait –the first thing I see is the fright-wig self-portrait, c. 1986. Although in the long run I might prefer his “silence” self-portraits, done earlier (those with his index finger to his lips), the fright-wig Andy is Andy too.

Upstairs I particularly love Elvis (Eleven Times) from 1963, and, of course the Silver Pillows, and the Double Last Supper isn’t bad either. The Warhol also is a venue for traveling shows, such as, presently, The Downtown Show, a survey of downtown art of the ’70s and ’80s (which I had already seen at the Grey Art Gallery in N.Y.C., and there are guest-curator shows such as the current The F-word (meaning female, feminine, feminist) curated by Liz Thomas, with “interventionist” works by Yoko Ono, Carolee Schneemann, Martha Rosler, Deborah Grant and others.

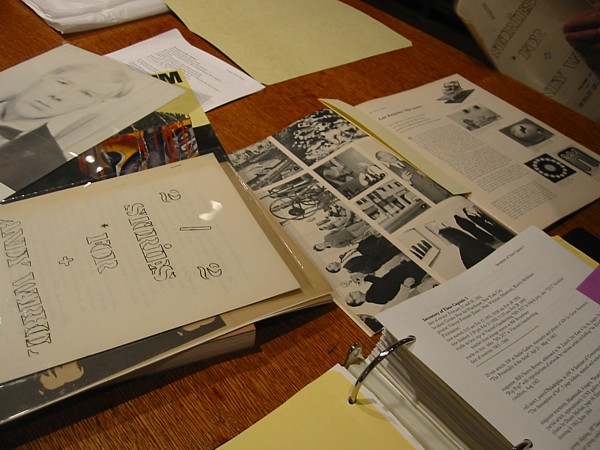

But the real treat was being guided through a sampling of one of Warhol’s Time Capsules bythe Warhol archivist. Warhol was, as proven by a famous auction of his collectables at Sotheby’s in 1998, a compulsive shopper. A collection of cookie jars went for $237,830. He couldn’t part with anything. Shopping bags full of flea market purchases were squirreled away and, apparently, he saved all his mail or, at least, let it accumulate. Someone, whose name is now lost to art history, had the idea — during one of the Factory (i.e. studio) moves –to put all the stuff in numbered cardboard boxes and thenceforth continue the projects with daily accumulations. Warhol liked that idea.

Time Capsules! Why not? The Warhol archivist has also found candy bar wrappers — Andy had a sweet tooth — and, inexplicably, insect-infested raw pizza dough. Once in his “Diary” Andy wrote: “I opened a Time Capsule and every time I do it’s a mistake, because I drag it back and start looking through it…” (The Andy Warhol Diaries, entry 5/24/84).

Matthew Wrbican, the assistant archivist, puts on the requisite white cotton gloves and opens Box 21. Some of the contents have already been placed in little plastic envelopes and all of it has been catalogued. I am particularly struck by a stapled , mimeographed offering by N.Y. School poet Ron Padget with a cover by Warhol (using stills from one of his films). The inventory printout identifies it as 2/2 stories for Andy Warhol published by C magazine. All ten pages are identical.

I once had that publication! Where is it now? Clippings, announcements, fan mail and several issues of the Village Voice (“very brittle condition.” “badly bent,” “yellowed.” “Dance column by Jill Johnston on Billy Kluver, yellowed.”

Time flies. Or is the phrase “time flees”?

We were sampling Time Capsule 5 (contents 1963-1965) . The Box 21 label was a hold-over from some old Factory numbering system. You can sample a Time Capsule on-line.

I did have an insight though. Warhol was indeed fascinated by celebrities and fame. He liked the idea of creating Super Stars, perhaps now forgotten, with his ground-breaking movies. Nico, Ingrid Superstar, Viva (named after the paper towels), Bridget Polk, Ultra Violet. And he enjoyed celebrities like Liza. But what he was really doing was figuring out how he himself could be famous. Hence the accumulations of mentions and pictures of him in the Time Capsule. I don’t know why he didn’t have a clipping service; but he seemed to just make piles of things:

Here’s my name again in print. Here is my picture. I must exist.

Nowadays we have the Google Game. To see which artist is most famous, Google the names for citations and images. How many artists now Google themselves daily to follow their ascent?

Andy, like Marilyn, was invented. Hollywood invented Marilyn: the hair, the eyes, the voice. You had to have a look that you stuck with. Von Sternberg invented Marlene. Andy invented Andy: the wispy, nasal, vague voice may have been his own, but he probably exaggerated it. And his silver wigs were definitely icon-making add-ons. And then he was shot in 1968. Although the assassination of Robert Kennedy pushed him off the front page, that sealed the deal. Fearful of hospitals, he died of a hospital oversight in 1987. He’s gone but still here.

On the theme of animals: When leaving The Warhol, I noticed, to the right, the stuffed dalmatian that once guarded the Factory on Union Square. Was it there before gun-touting Valerie Solanas barged in and therefore a failure or did it appear afterwards, like a lock on the door of an empty barn?

The Mattress Factory Tour

Jason Peters: Even in Darkness There is Light

One of those inspired projects that becomes an art hot-spot and involves into an essential institution, the Mattress Factory harkens back to an era when opportunities for art experiment were proliferating across the country. It has long focused on artist residencies set up to produce installations of one sort or another. The main site is indeed an old mattress factory in what still is a neglected neighborhood on the North Side. Cheap row houses along Spanish American War Street have been purchased as temporary digs for the lucky artists and additional exhibition spaces.

Of this year’s crop of ephemeral art efforts, I most liked Jason Peters’ plastic bucket sculptures and Ruth Stanford’sIn the Dwelling-House. Inside the abandoned house on Sampsonia Way, Knight has made objects and other works lifted from fragments of wallpaper found in this derelict working-class domicile: Neo-Plastic sculptures in the kitchen, for instance, derive from fragments of ’20s geometric patterns on the decaying walls. There’s a case too of all the glass bottles found throughout the building.

Ruth Stanford, In the Dwelling House

Not all the work at the Mattress Factory will disappear. One can always see Jene Highstein’s concrete sculpture that almost fills an entire room; two mirror pieces by the Yayoi Kasuma, three fine works by James Turrell, and Allan Wexler’s two-room living suite, with clever beds that shuttle through the dividing wall.

On the theme of animals: There’s a “drawing” done by raccoons on and over a fireplace ledge in Stanford’s Sampsonia Way house. Their soot-covered little hands left traces behind, as they scurried in, looking for food and/or motivated by curiosity.

The Carnegie Deli

Sol LeWitt: Wall Drawing,1986

I cannot believe I have not been to the Carnegie Museum before, but there I was, in front of me a giant Richard Serra and then in the lobby a Jean Dubuffet with moving parts, and a ramp with an immense (and immensely beautiful) Sol LeWitt mural.

Upstairs items from the Decorative Arts collection are routinely displayed along with paintings and sculptures; and European and American art are shown in tandum. This to non-museum insiders may seem banal, but it is nearly revolutionary. It is not that I think painting and sculpture are superior to the so-called decorative arts, craft objects, and design products (sometimes I think the reverse is the case), but that when they are seen together a visual culture is exposed. For instance, I did not know of Luis Dierra’s Plate Glass Chair, 1939; and there was Gerrit Rietveld’s 1920 Child’s Chair both near suitable abstract paintings. A whole wall and a kind of antechamber is taken up by the 1935 Chariot of Aurora wall decoration from the Normandie; retro-fitted in 1941 for the Ille de France, an ocean-liner I once took to France, oblivious to the Chariot of Aurora.

I was also delighted by the juxtaposition of a Kenneth Noland horizontal stripe painting and a Nakashima table. My favorite paintings were Marsden Hartley’s super-maudlin, self-dramatizing, self-portrait as martyr called Sustained Comedy (1939) and one of Willem de Kooning’s “Woman” paintings. But these are just teasers.

The Carnegie Internationals, are invitationals held periodically and a large part of the painting and sculpture collection (at least 19th Century to the present) are by policy purchases from same. It is a peculiar way of amassing art. Here and there are some fill-ins, non-Carnegie purchases, and gifts, which I assume have become increasingly important.

* * *

Extending Animals

Edwin Lanseer, Man Proposes, God Disposes (1863-4)

Finally, Co-curator Louise Lippincott was our guide to “Fierce Friends.” So I had some of my question answered. Why did they stop at 1900? Well, the Van Gogh Museum limits itself to 19th century art and culture and Andreas Bluhm, the other curator, and Lippincott are not trained as modernists. Similarly, non-western animal imagery in art is sidestepped. This is their second collaboration based on the interface of art and science: the first was “Light! The Industrial Age 1750-1900, Art & Science, Technology & Society.” An exhibition on the theme of artists and animals is even a better fit for the Carnegie since the art museum shares space with the Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Stuffed animal corpses could easily be borrowed, along with bird skins to be laid out next to appropriate Audubon illustrations. The exhibition even includes some choice lampworked glass, biological specimens by Leopold and Rudolf Blaschka.

The exhibition itself is more thematically organized than the catalog. Some themes examined in depth include animals as pets and companions (and the history thereof); animals as meat; animals as horsepower; animals as Guinea pigs; and animals in the imagination.

The power of an exhibition like “Fierce Friends” is that it makes one think of the animal-human interrelationship. Thus there are animal themes that also might have been included, such as: animals as protectors (guard dogs), animals as hunting helpers (retrievers and hounds), animals in sports and entertainment (racing, cock-fights, dancing poodles, cartoons). Some of these themes might be repulsive to some, but no more disgusting than animals as property or protein.

As someone who subscribes to the idea of our human stewardship, I welcome all of these angles on animal/human relationships. Animals are increasingly dependent upon us; and I don’t mean just poodles and Persian cats (who have trained us as their slaves). Missing in action are animals as spiritual symbols or emblems of self. Without animals could shamans, urban or otherwise, exist?

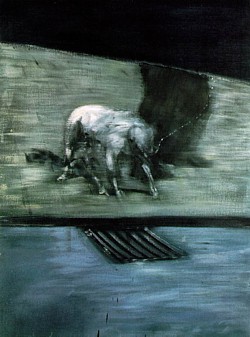

As an example of the complexity of the exhibition and the material under examination, I offer Edwin Lanseer’s Man Proposes, God Disposes (1863-1864). One might assume a Dawinian interpretation of the depiction of the shocking outcome of a failed 1847Arctic expedition. The explorers, however, were not done in and eaten by polar bears, as pictured, but succumbed to cannibalism. Of course polar bears can no longer illustrate the survival of the fittest; we now see them as stuck on broken, melting sheets of ice, unable to reach the seals they need for supper.

I do think it is a shame the exhibition stops at 1900, so here’s an album, no matter how attenuated, that might update and even further complicate the efforts of the two talented and learned curators:

Fierce Friends Update (An Online Exhibition)

Pablo Picasso: Baboon and Young, 1951

Francis Bacon: Man with Dog, 1953

Joseph Beuys: How to Explain Paintings to a Dead Hare, 1965

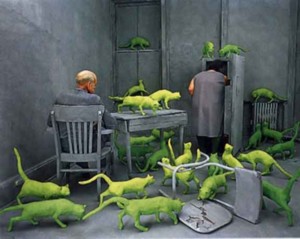

Sandy Skoglund: Radioactive Cats, 1980

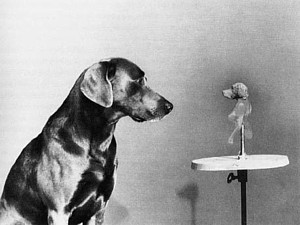

William Wegman: Man Ray with Sculpture, 1982

Damien Hirst: The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living,1991

Jeff Koons: Puppy (Rockefeller Center), 2000

Kiki Smith: Rapture. 2001

Kiki Smith: Rapture. 2001

FOR AN E-MAIL ALERTOF NEW ARTOPIA ENTRIES CONTACT perreault@aol.com