H�LIO OITICICA …AND BICKERTON AND CLARK, TOO

Ashley Bickerton:Green Reflecting Heads #1(2006)

In Search of the Exotic

What is exotic? The Other – demon of post-modernism – was the Double that haunted Romanticism. But, excuse me, the Other lives next door. I have really no idea of what’s going on in the brain of that birthday celebration family, making such a sit-com racket. When I buy a quart of 2% it is not the harried young man from Mumbai behind the counter who is the Other but the woman in the line behind me who is muttering obscenities and is wearing clothes from 1972.

The lives of the favela denizens as depicted in the Brazilian series called City of Men (a TV series offshoot of Fernando Meirelles’ brilliant City of God) are less exotic than New Yorkers that live on the Upper West Side. Both Cities were shot in real-life favelas, those cliff-perching, ad-hoc slums of Rio; City of Men can now be seen on BBC-America. Does anyone remember the South Bronx or Bushwick before the artists started settling in? Or Lower East Side squats? On another level, the school yard bullies from my New Jersey childhood have merely been transformed on screen to favela drug lords. Slums, no matter how picturesque they look from sea level (let’s say, Ipanema beach) are not exotic, nor do I see any reason to romanticize them.

In one episode of City of Men, two boys descend from their favela in search of what they think is a name on a return address. Never mind why. They are amazed that the streets in this truly exotic, rich person’s neighborhood have names; their favela “streets” have none, making mail delivery very difficult indeed. Since the series seems determined to be heartwarming, they concoct a scheme to sell street-naming rights to their friends and neighbors in the favela.

In terms of the exotic, we need not think too much about Ashley Bickerton who was once lumped together by the Sonnabend Gallery with the other oddities of so-called Neo-Geo, which was really Neo-Pop. The guy was famously a surfer; and Bali, where he has lived now for quite awhile, is another one of those catch-a-wave Valhallas, like the north shore of Oahu or certain favored beaches in Australia. Does this qualify as exotic?

A just-closed duel-gallery survey at Sonnabend and Lehmann Maupin made me think Bickerton, now removed to foreign climes, is better than I thought. His pro-ocean, anti-pollution stance was way ahead of its time in spite of a personal slam from critic Peter Scheldahl, as recounted by Bickerton in an unfortunate 2003 interview in Artforum:

I was never trying to be some pontificating pulpit pounder. Unfortunately they thought I was. Peter Schjeldahl once wrote, “I no more want to hear Ashley Bickerton giving dissertations on industrial farming than I want to hear a bunch of farmers discussing Kiefer.”

Schjeldahl, sometimes unaccountably conservative, loses again.

Now wise guy Bickerton’s preaching looks positively visionary; and I do like the Bali ex-pat images and the artist’s goofy, gap-tooth look. Bickerton’s new green-headed water-spirits are also just right. But Bali is not Tahiti; in fact, as I know personally, Tahiti is not Tahiti.

* * *

H�lio Oiticica and Neville d’Almeida, Cosmoco, C-Print, 1973-03

Quasi-Cinema In Search of Time

Further back in time, in many ways closer to home, yet weirder and more exotic than Bickerton’s Bali, is the work of H�lio Oiticica (1937-1980), a lean example of which is now at the Galerie Lelong (528 West 26th Street, to June 17). Billed as a collaboration with Oiticica’s brother Neville d’Almeida, it is called “Cosmoco Programa in Progress – Quasi-Cinema CC1 Trashiscapes.” The main event is a reconstruction of Oiticica’s 1973 “Quasi-Cinema” installation originally made for the small East Village apartment he called Babylonests.

The website blurb for the ’02 Oiticica Whitechapel Gallery exhibition defines Quasi-Cinema as:

…experiments in film and slide projections, carried out in New York in the 1970s. These room sized installations – CC1 Trashiscapes, CC3 Maileryn and CC5 Hendrix-War – incorporate mattresses, emery boards, sand dunes, balloons and hammocks to create alternative auditoriums or viewing environments. Each installation has its own soundtrack: discordant music after Stockhausen, ‘archetypal’ Brazilian music and songs by Jimi Hendrix, multiple images of cultural icons such as Luis Bu�uel, Marilyn Monroe and Hendrix are simultaneously projected onto the walls and ceilings. Some of the images are retraced in cocaine which Oiticica used as a reference to Inca spirituality and medicinal practice – a symbol of resistance against American imperialism and a comment on both the cosmetics industry and notions of plagiarism in art.

If you believe cocaine is “a symbol of resistance against American imperialism” you will believe anything. The way cocaine is distributed is a confirmation of the principles of American imperialism, in so far as that imperialism is capitalistic. And since he died before the onslaught, we don’t know what Oiticica might have thought of crack.

The current re-creation has facing, identical slide projections of a cover of a New York Times Magazine, featuring Luis Bu�uel, with various abstract drawing or “lines” of white powder superimposed. The room is dark, dark. And there are mattresses and pillows covered in black fabric. And the sound of glorious Brazilian pop. There is also, by the way, to complete the re-packaging, a room of C-prints made from the slides. They are really quite beautiful, oddly enough.

Obviously, coming to grips with the art of H�lio Oiticica means overcoming numerous obstacles, not the least of which is time in all its aesthetisizing forms. Drugs are no longer amusing.

The exotic is just another name for out-of-context. I perceive Oiticica’s art as alien rather than exotic. No matter how we re-contextualize Oiticica, he still seems to come from another planet. And not just Planet Rio. Or Planet East Village.

In regard to the latter, he was on board in the ’70s when the Lower East Side was being reinvented by the developers as the East Village. I lived on 8th Street and Avenue D and showed in a gallery on St. Marks Place and I remember how shocked we were when a big brick apartment complex on First Avenue was advertised as located in the East Village. The East Village? None of us, poets, artists, Beats and Bohemians had any inkling that we had been living in the East Village, and not the ratty old Lower East Side, rapidly being colonized by junkies and slowly being burned to the ground. This was to make way for the real estate boom that would be caused by a new East Side subway line, long planned, and even now not actualized.

Yet Oiticica was Brazilian and what do we know about Brazilian art? How European is it? How African is it? How indigenous? We may know Villa Lobos hits, samba favorites, and The Girl from Ipanema; but we don’t know Oiticica and Lygia Clark (1928-1988), the two world-class Brazilian visual artists. “Visual” artists? Everything has to be put within quotation marks. Clark’s late work seems to have been primarily about touch, weight, and healing. Oiticica’s cannot be understood without music, motion, and nesting.

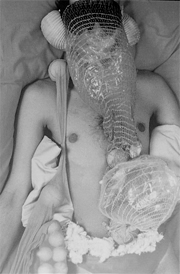

Lygia Clark, Untitled TherapeuticRitual c. 1978?

In Search of Art with Another Agenda

Although I cannot say that I knew either, I did meet both. Clark, I met through French critic Pierre Restany (who years earlier had “discovered” Yves Klein and thus cinched his own aura) was shepherding Clark around New York in the late ’60s. She was doing her introductions piece so I too shook hands with her. I think she was wearing gloves. Could that be?

Simone Osthoff’s fascinating article, “Lygia Clark and H�lio Oiticica: A Legacy of Interactivity and Participation for a Telematic Future,” available on Leonardo On-Line, has a precise description of Clark’s best work:

In the last phase of her work, Clark employed a vocabulary of “relational objects” for the purposes of emotional healing. Objects made of simple materials such as plastic bags, stones, air, shells, water, sand, styrofoam, fabric and nylon stockings acquired meaning only in their relation to the participant. Continuing to approach art experimentally, Clark made no attempt to establish boundaries between therapeutic practice and artistic experience, and was even less concerned with preserving her status as an artist. The physical sensations caused by the relational objects as she used them on the patient’s body, communicated primarily through touch, stimulated connections among the senses and awakened the body’s memory. Clark’s use of relational objects in a therapeutic context aimed at the promotion of emotional balance.

I met Oiticica through the Argentine artist Eduardo Costa who had known him in Rio. Oiticica had a nest in the 1970 “Information” show at MoMA, but I never climbed into those dark cubicles nor did I once visit his Quasi-Cinema installations in his East Village apartment. I am not even sure they were open to the public. Probably just as well. Then I was physically (literally) repelled by participatory art. I was “all eyes.”

You need to know both Clark and Oiticica come out of the Brazilian Neo-Concrete Movement, which is basically DeStijl via Ulm and Max Bill. How on earth did the tradition of straight lines, flat color and rectangles ever get established in Brazil, a country without straight lines, flat colors and rectangles? Was it the need for balance?

Oiticia: Grand Nucleus, 1960

Once when I was in Brazil (I have been there three times), I was lucky enough to have access to the Oiticica “museum,” an apartment maintained by some friends of his and saw a few of his hanging rectangle pieces. My hostess, Esther Emilio Carlos, a Brazilian art critic and former gossip columnist for O Globo — and known far and wide, if sometimes ironically, as the angel of the avant-garde — was an important Oiticica fan.

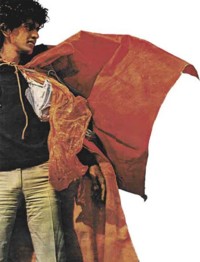

It was the Parangol�s, however, that established the artist’s importance. I have never seen his Parangol�s (“capes”) in action. Only photos. Somehow Oiticica moved from primary colors (or off-primary) during his Neo-Plasticism period to pigment in glass jars, to fabrics; then fabrics to be worn — by the Mangueira favela Samba School he became associated with. Samba Schools engage in a year of collective work for the carnival parade involving, as now everyone can see on television every year, theme songs, dance moves, and over-the-top costumes.

Here is what Oiticica wrote:

The rehearsals themselves are the whole activity, and the participation in it is not really what Westerners would call participation because the people bring inside themselves the “samba fever” as I call it, for I became ill of it too, impregnated completely, and I am sure that from that disease no one recovers, because it is the revelation of mythical activity. . . . Samba sessions all through the night revealed to me that myth is indispensable in life, something more important than intellectual activity or rational thought when these become exaggerated and distorted.

Was Oiticica, the son of a university professor, romanticizing and exoticizing the poor? Or carrying forward his grandfather’s anarchism? Had he, of European descent, fallen under the spell of the African religions? Mornings, before the one million Carioca sun-worshippers come to display themselves — the men standing — you can find flowers and burned-down candles on the Copacabana beach.

Oiticica apparently invented the ironic term Tropic�lia, used for a certain kind of post-Bossa Nova, often political (i.e. anti-dictatorship) Brazilian music. I have the 1992 catalog to the Oiticica traveling exhibition (it came to the Walker in Minneapolis). The catalog is a great resource, with a terrific sampling of writings by the artist. In it I found a black and white photo of Brazilian pop star Caetano Veloso wearing a Parangol�. Later I found it in color on the internet.

Gaetano Veloso wearing a Parangol�

Are there any Parangol�s left to see, to wear? Why had I forgotten that they include words? What would it feel like to wear a Parangol�?

Fortunately I found this account by Ana Dezeuze in her excellent article “Tactile Dematerialization, Sensory Politics: Helio Oiticica’s Parangol�s” (Art Journal, Summer 2004):

If the Parangol�s span the repertories of erudite and popular cultures, they do not, however, iron out the tensions between the two. For just as the Mangueira dancers provoked a disruption by leaving the context of the carnaval to enter that of the museum in 1965, I, a white, European, middle-class art historian, can only feel uneasy about the distance that separates me from the culture of the favela when I put on a Parangol�. If part of the experience of the Parangol�e lies in discovering the object by one’s self, its other dimension consists in revealing these hidden elements to others through one’s own movements. After all, the bright colors and shiny fabrics are the same as those worn by samba dancers in the spectacular Rio carnaval, and the short texts included in the Parangol�s act like speech bubbles transforming the wearer into an enunciator as well as a reader. Oiticica described this double experience of the individual–at once private and collective, intimate and spectacular–as the ciclo “vestir-assistir” (wearing-watching cycle) of the Parangol�, which includes the experiences of wearing, watching, and looking while being looked at…. My own self-consciousness increased as I wore the Parangol� outdoors and a woman walking in the park came over and asked me what was stenciled in white capital letters on my banner. “Sex and violence, this is what I like,” I replied. Seeing the appalled look on her face, I felt suddenly uncomfortably aware of the statement that I was making to others, as if I were carrying a political banner in a demonstration.

AFRAID OF MISSING AN ARTOPIA INSTALLMENT? E-MAIL PERREAULT@AOL.COM AND YOU WILL BE NOTIFIED WHENEVER THERE IS A NEW ESSAY.