Hesse, Aught, 1968

A Matter of Life and Death

The new exhibition of prime sculptures by Eva Hesse (1936-1970), now at the Jewish Museum (1009 Fifth Avenue, to Sept. 17) calls out for some examination of the theme of art and biography:

Biography has figured prominently in the criticism and scholarship about Hesse’s work. Born into an observant Jewish family in Hamburg in 1936, Hesse and her older sister were sent to Holland on a children’s train at the end of 1938. Their parents fled Nazi Germany too months later and the family came to New York…

So says the introductory wall text.

The famous kindertransports certainly are disturbing, but not as disturbing as the six million children and adults who did not have the opportunity or the means to escape Hitler’s Germany.

And, oh yes, as we all known that when the wall texts says “her premature death in 1970,” it means she died of a brain tumor after having only one solo exhibition in New York. I still remember her appearing at a Whitney opening after her first operation, in a wheelchair, her head half-covered in white bandages. Was her appearance bravery, pride? Two more operations and she was dead. I was shocked.

But what, if anything, does this have to do with understanding her work?

The World of Yesterday

I was struggling to get into this delicate topic when suddenly it occurred to me that I have been reading The World of Yesterday, a memoir by Stefan Zweig (1881-1942). It too is a kind of European horror story. He does not mention the kindertransports — which I am sure he knew about — but he does convey the displacements and disappointments of his “three lives” as a European Jew, born in Vienna in the late 19th century. What he calls the “age of security” (a false security, of course) yields to the First World War and then to the rise of Hitler when all of his books were burned. By his own account,Zweig was once the most translated authors in the world, but I suspect that his biographies of great men were the cause, not his fiction and plays.

Zweigfinally moved to England and then to Brazil, where he and his second wife committed suicide in the mountain city of Petropolis outside Rio, where Pedro II, the Emperor of Brazil, built his summer palace. Yes, there was an emperor of Brazil. His grandfather, in fact, to avoid Napoleon, made Rio the de facto capital of Portugal. Petropolis, an hour away from Rio, is a charming mountain town I once visited. I remember jungle flowers seen from the busduring our ascent. I remember we had to walk in our socks across the highly polished floors of the silent palace. Zweig was probably attracted to Petropolis because there were many German immigrants there. If you are interested in Zweig’s suicide note,it is appended below.

Technically, my interest in Zweig started by reading the newly reissued novella The Chess-Player. And then I found his dire tale of a professor and his male student called Confusion. He is not Kafka; he is not Borges. His tales are half Vienna Secession, half postmodern. But best of all, because it seems to have something to do with art economics today, is The Invisible Collection. Like most of his tales, it is a story within a story (sort of) with a possibly unreliable narrator. The latter is Zweig’s only full-blown modernist trait.

Here is the short version of that short tale:

An art dealer, during hard times when people are putting their money into art to protect their wealth,is running out of art to sell. So he looks up an old client who had purchased many important drawings from his father, who had been an art dealer too. He is amazed that the man, of extremely modest income, is still alive. The dealer visits, thinking he might be able to get some of the now very valuable prints and drawingsfor resale. The collector is enthusiastic about showing his prized collection of prints and drawing. He is, however, blind. Before the dealer looks at the art, the old man’s daughterpulls the dealer aside and warns him that she and her mother, long ago, had begun selling off the artworks in order to survive, substituting blank pieces of paper identical in shape, weight and size to each of the missing artworks. The dealer waits patiently as the blind collector shows him each blank piece of paper with a full and loving description of the artwork it is supposed to be, the artwork he vividly remembers. Surmising that the old women probably sold the art for very low prices, the dealer knows what they are worth now in a period of insane inflation. Knowing some of the missing prints himself, as the blind collector goes through his cherished collection, the dealer chimes in with relevant comments.

Now here is the question: To understand this story, do you have to know that Zweig came from a wealthy Austrian family, that he published cultural commentaries in the prestigious front page feuilleton section of The Vienna Free Press? That the only young man to be so honored before him was Hugo von Hofmannsthal, poet and librettist for Richard Strauss’s Der Rosenkavalier? That Zweig himself wrote a libretto for Strauss? That he himself collected autographed manuscripts? That he was a pal of Sigmund Freud and friendly with Rilke and Pirandello?

The story is the story and in this case is quite complicated enough, more complicated than it first appears.By the way, to understand my liking for Zweig’s rather off-putting, terse novellas — and perhaps my dislike of his autobiography — do you have to know that I am of Austrian descent? At one point, I discovered that my grandfather on my mother’s side, who I always thought was Polish (he spoke Polish, he acted Polish, and he looked Polish, whatever that is) actually came to America with an Austrian passport. Solution: In those days, Poland, poor Poland, was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

* * *

Although it is probably impossible to look at Hesse and avoid thinking about trains and brains, about kindertransports and unexpectedly fatal tumors, about life’s disasters and the tragedy of early death, it might help to try. After all, Hesse, when you cut through the latter-day romanticism that has been applied by well-meaning fans, was in that first generation of what I call artists-by-degree; her teacher at Yale was Josef Albers. Both Sol LeWitt and the critic Lucy Lippard were close friends and supporters. Now that’s important. Even more important, she had enormous talent.

Her works, however,are not autobiographical, the way, for instance, Joseph Beuys’s tend to be. After all, Beuys used fat and felt because that’s what Siberian shepherds wrapped him with to save his life when, as a Nazi pilot, he was shot down and left for dead. When you see his famous fat sculptures, the fat is just not an impersonal material, the way latex and fiberglass is in a Hesse work. When he hides under a felt blanket while living in a cage with a coyote, there is a reason the blanket is felt and not cotton, whereas in Hesse even latex is stripped of kink.

If there is indeed a relationship between Hesse’s life and her art, it is non-autobiographical, indirect. We can look at her hanging rope pieces as other than diseased ganglia. Or can we?

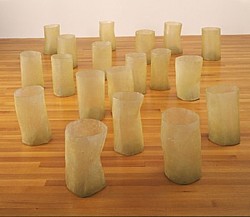

Hesse, Repetition Nineteen, III, 1968

How Post-Minimal Is It?

First there was minimalism: form without composition. Then a few years later, there was anti-form, which was minimalism without straight lines. What they had in common, aside from the high-end, art-world sociogram that connected most of the artists (and the fact that some artists moved rapidly from one posture to the next , like Robert Morris andRobert Smithson),was a united front against “composition,” meaning cubism or the push-pull of Hofmann and de Kooning. All parts, if there were such, were to be equal rather than connected in some kind of internal hierarchy.

Some would prefer to think of anti-form as post-minimalism, but as practiced by Hesse, Morris, Richard Serra (with his tossed molten lead and his mixtures of rubber and neon), the forms, materials, and gestures were severely reduced; they were just not rigid or geometric. Furthermore you could not look at Morris, Hesse, and Serra in this brief period without thinking of Claes Oldenburg’s soft drum set as the antecedent. Or, perish the thought, of Marcel Duchamp’s Three Standard Stoppages, with shapes determined by dropping particular lengths of string. Most of the minimalists, by the way, were against Duchamp(with the exception of Morris), seeing him as a sort of a rich person’s clown. And surrealism was too decadent. But — wait a minute — didn’t the minimalists entertain the founders of the Dia Foundation? Isn’t there something decadent about finish fetish and perfect edges? And all that expensive space that minimalism requires for proper display?

Nevertheless, when it came to anti-form minimalism,the use of gravity was not exactly automatism, but somehow a kinder, more logical version of chance. And was not a path to expression, but another way around it.

Now, however, 38 years after Hesse’s one and only one-person show in N.Y. (at the Fischbach Gallery in 1968), it’s clear enoughthat there are qualities in her work that had nothing to do with letting gravity or accident do the work — or the anti-composition strategy. How about tactility and translucency? How about a feeling for plastic and latex, materials which until Hesse only a Futurist could love?

Can we look at the Hesse sculptures without the sentimentality the current room of snapshots and ephemera forces into one’s consciousness? Fortunately, these documents are at the end of this short exhibition, so you can see the work without the petty details of the autobiography or the pages of her father’s tagebucher (scrapbook diaries) devoted to lovely baby Eva. These daybooks, by the way, are moving in themselves and of some graphic and obvious sociological interest, worthy of publication in reproduction. But do they add to understanding the grownup’s art work, a small oeuvre that has had enormous influence? I don’t think so.

Does the work reflect displacement? If so, it is a displacement, although troublesome of course, not too different from displacements others have experienced, before or after Hesse’s generation. It is simply too easy to see Hesse’s brilliant use of relaxed forms as an expression, first of all, of her briefly disrupted childhood and, secondly, equally problematically, of her deadly illness.

I would rather have seen in the exhibition (as well as in the catalog) examples of art contemporary with hers, made by friends and acquaintances and even other artists such as Beuys that would provide a deeper context for her work than the specious proximity of biography, biography, biography. Beuys’ felt and fat sculptures were certainly known in the late ’60s in New York, through photographs and rumor. Although it might contest the outmoded etiquette of both exhibition and catalogue practice, one of Donald Judd’s multiple-box wall pieces next to her masterpiece Sans II, 1968, a wallpiece composed of irregular fiberglass boxes, would have said more than anything now offered in that sad but irrelevant room of documents.

The ephemera is no more meaningful than the opaque artist’s statement (written for the Fischbach solo exhibition):

I would like the work to be non-work. This means that it would find its way beyond my preconceptions.

What I want of my art I can eventually find. The work must go beyond this.

It is my main concern to go beyond what I know and what I can know.

The formal principles are understandable and understood.

It is the unknown quantity from which and where I want to go.

As a thing, an object, it accedes to its non-logical self.

In its simplistic stand it achieves its own identity.

It is something, it is nothing.

The Little Stuff

This exhibition of only 35 artworks, however, proves you don’t have to live till you’re 100 and produce tens of thousands ofpieces to be an important artist, grinding out prints and variations that can hardly pass muster as souvenirs. Sometimes, as here, six major pieces in four short years are enough. The little stuff doesn’t count.

There’s even some humor in the oddball, irregular forms. If, no matter what the artist intends, every sculpture is a statue, then Hesse’s big pieces are paeans to the sagging and slumping that flesh is heir to. There’s more to bodies than muscle and bone, in both men and women.

In any case, I am obviously reminded that post-minimalism was a misnomer, and not only for works of the anti-form ilk (like Hesse’s major achievement), but in terms of Body Art and Conceptual Art too. The paring down never stopped; it was applied to different materials and slightly different ways of making things. Art needed to say it had to be in service of the brain and not in bondage to the eye, the heart, or the unconscious. Thus, wiped clean, the eye, the heart, and the unconscious could reappear in fresh, more telling ways.

Now that classic minimalism seems more expressive than it first did, Hesse’s anti-form seems less expressive, less a break with colleagues who had already explored the straight and the narrow, and more an extrapolation into the irregular and the fuzzy.

Addendum:

Before parting from life of my free will and in my right mind, I am impelled to fulfill a last obligation: to give heartfelt thanks to this wonderful land of Brazil which afforded me and my work such kind and hospitable repose. My love fro the country increased from day to day, and nowhere else would I have preferred to build up a new existence, the world of my own language having disappeared fro me and my spiritual home, Europe, having destroyed itself.

But after one’s sixtieth year unusual powers are needed in order to make another wholly new beginning. Those that I possess have been exhausted by long years of homeless wandering. So I think it better to conclude in good time and in erect bearing a life in which intellectual labor meant the purest joy and personal freedom the highest good on earth.

I salute all my friends! May it be granted them yet to see the dawn after the long night! I, all too impatient, go on before.

Stefan Zweig, Petropolis, Feb. 22, 1942

(The World of Yesterday, University of Nebraska Press)

For an Artopia Alert eveytime a new essay is posted contact: perreault@aol.com