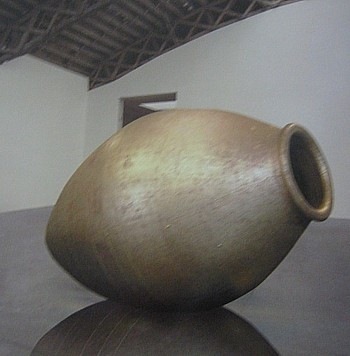

James Lee Byars, The Spinning Oracle of Delphi, 1986

Silence Is Indeed Golden

Two years after the Whitney presentation of the gold-leafed room withbier,called The Death of James Lee Byars (1994), a multi-gallery presentation of mostly late work by the late James Lee Byars (1932–1997) forces a further reexamination of that willfully strange and, alas, sometimes too whimsical artist.

In concert, the exhibitions are titled “The Rest Is Silence.” Participating are the Mary Boone Galleries at 541 West 25th Street to June 23 and at 745 Fifth from May 18 to June 24; Perry Rubenstein Gallery to June 24 at 527 West 23rd Street, 526 and 534 West 24th Street, to June 24; and the Michael Werner Gallery, 4 East 77th Street also to June 24.

Klaus Ottmann, the curator of these current, multiple manifestations was also responsible for the 2004 retrospective in Frankfurt. In the otherwise convincing catalog essay for that event he not only ranks Byars as equal to Andy Warhol and Joseph Beuys but claims that he has, more than either, “given his age its complexity.” I don’t think so.

Let me explain.

Ottmann does admit that Byars’ American minimalist and conceptualist peers were not impressed by him, yet he apparently had a friendship with Beuys, a truly great artist, which may make up for that. Although Byars’ dissolving paper streetwork (The Great Soluble Man, 1967) was perfect for what it was and I certainly liked his dress for a hundred people that afforded a grand climax for my Fashion Show Poetry Event, I remember him as always being vague and irritating. To some he was truly annoying. No wonder he was always trying to disappear.

Of course, he was still becoming “James Lee Byars,” evolving from his background as a paper and cloth or clothing artist (craft-matrixed) to an artist on paper, i.e. artist as a verbal concept. His personal costumes were affected and silly, childlike or childish (?) versions of Beuys’ hat and vest. Having known a few living legends, I know one when I see one. And Byars, although apparently convinced he was a living legend, simply wasn’t. Quite yet.

He had to die first.

Looking back now, when he first appeared in New York he was trying to capitalize on the fact that he had lived in Japan — as, it turns out, an English teacher. He was influenced by and attempted to accrue the prestige of Zen and the Noh theater. But his koans were not real. He did his thing at The Architectural League, failed at his question project, and then for all practical purposes he disappeared, i.e. spent a lot of time in Europe, where, it now appears, his act seemed to work. Sometimes you have to disappear to become who you are.

I should note here that John Brockman, a Byars friend and supporter, points out that Byars’ World Question Center – which was to bring together 100 brilliant minds to ask questions of each other – resulted in 70 telephone hang-ups. Perhaps Byars wasn’t smart enough to identify really100 great minds. Perhaps great minds are not interested in other great minds. Perhaps they don’t want to be locked in a room with other great minds and forced to listen to 99 questions that other supposedly brilliant thinkers have been asking themselves. Perhaps great minds have answers, not questions.

If you find this project endearing, then you will also find how Byars “stalked” or charmed curator Dorothy Miller and convinced her to let him install one of his paper sculptures in a MoMA stairwell charming too.

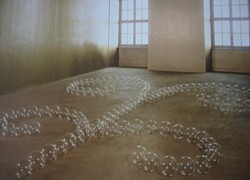

James Lee Byars: The Angel, 1989

Questions?

But all is forgiven. Time and distance are sometimes the best curators. Thus, years after his death in Cairo (of a large, round tumor in his stomach) his sculptures emerge as a cool mixture of the splendid and the banal. This time around we particularly like The Spinning Oracle of Delphi at Boone Chelsea and The Angel, composed of 125 blown glass spheres at Werner. Perhaps they represent a kind of stage-set mysticism; perhaps they are real. Perhaps they are both. But in general, does all that marble and gold leaf Byars used make fun of the art world or is it genuinely poetic?

It may be awful to say this, but some artists get in the way of their art. We no longer have James Lee Byars to kick around. His persona, one assumes totally constructed, was persona non grata. Too fey, too arch. Did he really, as Ottmann claims, synthesis Conceptual Art, Minimalism, and Fluxus? And if so, why? Or was he The Trickster we yearned for?

Perfect this, perfect that. Hey, perfect is not what it’s all about. Byars was an aesthete with a moronic aesthetic, for surely he must have understood that perfection is not of this world. Or was that his point?

It is not only the Victorianism of Byars’ oeuvre but, less interestingly, the performative aspect that makes it stand outside of art history as now practiced. The art discourse, despite several banal books on art performances, does not really include non-object modes of art in any convincing way. Performances remain advertisements for the stuff that can be sold.

* * *

The Cheshire Smile

As much as I like some of Byars’ sculptures — even the flag from his short film Two Presidents, 1974 — my favoritework is his The Perfect Smile. A related piece, The Perfect Kiss, will be performedby a Perry Rubenstein Gallery staff member every day at noon and it is no doubt just as mysterious. According to Ottmann The Perfect Smile was the first performance to enter a museum collection (presented to the Museum Ludwig in Cologne by the artist in 1994): “The performance consisted of a very subtle movement of his mouth to indicate the briefest smile possible, before it vanished from his face.”

Don’t miss an installment of Artopia! To be placed on Artopia Alert List send your e-mail address to perreault@aol.com