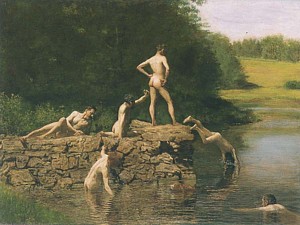

Thomas Eakins, Swimming, 1883-1885

Thomas Eakins: Untitled Photograph (students posing nude), 1883

Off With the Cloth

Anyone interested in realist painting will be fascinated by Thomas Eakins (1844-1916), whose disquieting endeavors, according to author Henry Adams, have been long misinterpreted. Eakins Revealed: The Secret Life of an American Artist (Oxford University Press, 2005) spills the beans. Now at last I know why, even as a mere child, I was attracted to Swimming (1883-85), The Gross Clinic (1875), and those paintings of sculls in the Schuylkill River, the idyllic ribbon that flows through Philadelphia’s Fairmont Park.

Eakins, in one of those larger-than-life art history moments, pulled a loincloth off a male model in front of some female students at the Pennsylvania Academy of Art in 1886. We are not quite certain if this was the only reason he was dismissed. No minutes of the Academy Board were kept, but he apparently had the habit of pressuring both male and female students to pose in the nude to demonstrate their commitment to the nude and only the nude as the didactic tool for learning how to make art. He even offered himself in the buff. Rumors persisted that not only had he driven two women into madness, but that incest, bestiality and sodomy (the latter two items often interchangeable then in the popular mind) were not unknown among his panoply of vices and offenses, fancied or not.

Adamsdoes demonstrate that Eakins, contrary to Lloyd Goodrich’s hagiographic monograph, was not a nice guy, but was rude, sloppy, slobbery (perhaps from therapeutic opiates), clearly bipolar and an exhibitionist/voyeur. Furthermore, although we are not privy to his bedroom proclivities, we know that, although married, he seemed to prefer the handsome Samuel Murray for studio companionship, country and seaside larking, and public dining. It was Murray, 15 years younger, and not his wife, who held Eakins’ hand when he was dying. His wife, after Eakins’ death, insisted he never painted from photographs and tried to change the title of Swimming (which reveals naked boys at play) to The Swimming Hole and then to the even more sentimental The Old Swimming Hole. The finished painting shows Eakins himself neck deep in the water staring at the winsome, buck-naked colts.

I am not sure that Adams is always correct in his interpretation of snapshots of Eakins: does he really look depressed? Is he a maniac, or is it the camera?

But Adams is certainly right in nailing Goodrich, once director of the Whitney Museum of American Art, for creating the deceptive view of Eakins as manly, honest, and forthright, posing him as virtuously all-American and the dubious precedent for the all-American representational painters Goodrich was promoting then: Reginald Marsh, John Sloan, Edward Hopper, etc. In reality, Eakins had a high-pitched voice, affected volunteer fireman’s clothes and often painted in his underwear; failed his classes in Paris, told dirty jokes, was “feminine,” was not exactly fond of women, was never much of an athlete, and drank a quart of milk with every meal. Adams, a bit of an amateur shrink, has fun with that last item, but does explain that milk was then a treatment for depression, at least according to the specialist Eakins visited after he was fired from the academy and had what we might call a nervous breakdown. The specialist in such things was a certain S. Weir Mitchell, author of Fat and Blood.

But Adams is certainly right in nailing Goodrich, once director of the Whitney Museum of American Art, for creating the deceptive view of Eakins as manly, honest, and forthright, posing him as virtuously all-American and the dubious precedent for the all-American representational painters Goodrich was promoting then: Reginald Marsh, John Sloan, Edward Hopper, etc. In reality, Eakins had a high-pitched voice, affected volunteer fireman’s clothes and often painted in his underwear; failed his classes in Paris, told dirty jokes, was “feminine,” was not exactly fond of women, was never much of an athlete, and drank a quart of milk with every meal. Adams, a bit of an amateur shrink, has fun with that last item, but does explain that milk was then a treatment for depression, at least according to the specialist Eakins visited after he was fired from the academy and had what we might call a nervous breakdown. The specialist in such things was a certain S. Weir Mitchell, author of Fat and Blood.

Crazy mother, overbearing father (wouldn’t let anyone speak at the dinner table), lower-class background, homely wife, hardly any market for his paintings, Philadelphia air — Eakins was a miserable fellow. The exhibitionism and love of embarrassing others is easily resolved into a big-time case of infantilism. There he is at the end in a wonderful photograph: fat-ass, bare-ass Eakins, around 1909, splashing into the river at his fish-house encampment, with who looks to be his devoted friend Murray standing by. Eakins, happy at last.

Samuel Murray and Thomas Eakins, c.1891

Thomas Eakins, Portrait of Samuel Murray, 1889

The Love that Dares Not Speak Its Name: Photography

Adams, it should be noted, draws upon information from the Charles Bregler Thomas Eakins Collection (ironically now owned by the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts). The collection, rediscovered in 1984, contains documents and many, many photographs from Eakins’ studio, all rescued by his former student Bregler and squirreled away for years. From these it is more than clear that not only The Fairman Rogers Four-in-Hand (1879-1889) was photo-derived, with its up-to-date presentation of horse gait and blurred carriage wheels, but, until the late portraits, so was almost everything else.

Since Adams is mercilessly condescending to the catalog for the Philadelphia Museum of Art’s 2001 Eakins retrospective, of course I had to dig it up. It is quite a tome (and, alas, like many catalogues, without an index); here Eakins remains the greatest American artist of the 19th century, the greatest unexamined American artist. There is no revisionism here, but details, details, and what amounts to promotion for Philadelphia’s favorite artistic son. No warts, no shadows.

What is valuable, however, is Mark Tucker and Nica Gutman’s chapter “Photographs and the Making of Paintings.” They examined the photos in the Bregler Collection, used infrared analysis on the paintings, and looked close enough to see pinpricks and tick marks. Although he sometimes used the tried-and-true squaring-up method, internal evidence proves Eakins also employed a magic or catoptric lantern and traced projections, keeping his use of photography a secret. Photograph was apparently a bigger secret, I should add, than his relationship with hunky, swarthy Murray, a would-be sculptor of no discernable talent.

We also learn here (and in Adams) that Eakins patched together parts of various photographs; hence, in spite of his mechanical use of orthodox perspective, things don’t quite match up. Like Vermeer (another “realist” favorite of mine who himself used a camera obscura), Eakins invented a photorealism that is dreamy and uncanny. Adams points to The Champion Single Sculls (1871), where everything seems lucid, proper; yet, although champion Max Schmit and his single scull are perfectly reflected in the water, the clouds are not.

Apparently Eakins wanted us to think that everything one needed to know was in the art: the usual cover-up. And Goodrich thought we needed a candy-coated he-man of a hero. Although in my view Eakins was one of the great ones, knowing just a little bit more about him makes his art a lot more interesting. Was he a victim of Philadelphia Puritanism? I’m not so sure. What would we think now of an art professor who made his students strip and pose for each other and took off his clothes too?

Thomas Eakins with female model, 1885 (Pennsylvania Acacemy of Art)

Thomas Eakins in four poses, c. 1885 (Pennsylvania Academy of Art)

Thomas Eakins with female model, c. 1885 (Pennsylvania Academy of Art)

For e-mail alerts of new postings: perreault@aol.com