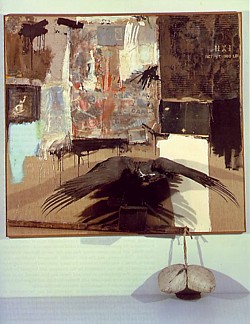

Robert Rauschenberg: Monogram, 1955-59

The Poetry of Things

If you have never seen Robert Rauschenberg’s iconic Bed (1955), Canyon (1959), or the free-standing Monogram (1955-59),or have some pressing need to see them together amid a number of lesser Combines, then you had better visit the current exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (until April 2).

You had also better see the exhibition if you really want to challenge yourself with questions of connoisseurship, art history and art criticism. The $45 paperback catalogue will no doubt explain the autobiographical and formal import of the artist’s signature stuffed animals, paint splashes and slashes, news photos and poster lettering. That may get you out of Port Arthur, Texas (birthplace of both Rauschenberg and, a bit later, Janis Joplin), but it won’t get you out of the good old days in Lower Manhattan, when Jasper Johns was Rauschenberg’s neighbor, and more, when images from Life Magazine and Time became fair game, and when Abstract Expressionism, then in its woeful second generation, was faltering.

Complaining about the pomposity in sway at the Cedar Bar and The Club, Rauschenberg told Calvin Tomkins (Off the Wall, Doubleday, 1980):

“They even assigned seriousness to certain colors,” and then, turning to the way the New York artists had infected Beat poetry: “I used to think of that line in Allen Ginsberg’s Howl, about ‘the sad cup of coffee.’ I’ve had cold coffee and hot coffee, good coffee and lousy coffee, but I’ve never had a sad cup of coffee.”

I have always found that a strange quote. Rauschenberg is known to be a generous man, not only to other artists, but to dancers and choreographers and even to poets. Heat one point turned over the chapel in his Lafayette Street building, once an orphanage, to John Giorno, Michael Benedikt and myself to produce one-night poetry performances. In the dark, taped poems booming, I inflated a giant weather balloon with helium so that it loomed above in the rafters; I also did my Whisper Event, whispering a one-line poem into individual ears of all and sundry.

I think there has always been a strain of poetry in Rauschenberg’s art, maybe not the sad and mournful kind, but the exuberant, even prophetic kind. This is, after all, the man who spent a whole year making illustrations for Dante’s Inferno. Is he against metaphor? Or against interpretation? Or just against bad poetry?

Robert Rauschenberg, Canyon, 1959

An American Picasso

Made from approximately 1954 to 1964, the Combines present mostly two-dimensional found materials held together with splashes and drips of paint, plus here and there the addition of 3-D objects. The bed that makes up Bed was Rauschenberg’s own, complete with pillow and quilt; Canyon combines an eagle and a pillow; Monogram features an Angora goat with its head through a rubber tire. These are all masterpieces. What other artists were doing or would do to extend the collage tradition into three dimensions was called assemblage. But Rauschenberg likes the term Combine, which he himself coined. He claims he was inspired by Calder’s use of the term mobile, invented to put people’s minds at ease. If you can give something that warps categories a name, then you have dispelled fear and perception becomes possible. The mobiles, as we know, are hanging sculptures that move, and the principle and the name is now used for mass-produced Day-Glo toys for every crib.

The Combines are both painting and sculpture– or, some purists would say, neither. They are best when they are least flat, which is why the silk-screen paintings that followed — in some ways products of Rauschenberg’s success, which allowed him to spend more money on materials — are not as interesting. Whether carefully considered or spontaneous, the Combines profit by their ad hoc aura, their found-art, apparently free-wheeling joy. No art is worth much unless the first reaction is “anyone could do it.” Well, as usual, it turned out that not anyone could make a successful Combine; in fact, many times — as proved by this gathering of Combines — even Rauschenberg couldn’t.

This is where connoisseurship comes in, or even art criticism. What makes one Combine a masterpiece and another, in the same room, just some meaningless stuff? I became an art critic to find out how to be an artist and how to make art. One principle is that great artworks are iconic, and they begin that way. In an unguarded moment, an artist friend once blurted out that an artwork did not exist unless it could be photographed. My refinement would be: unless it is photogenic. But just so we don’t get too wrapped up in media and Pop Art, let us finally say instead that an artwork has got to be memorable, which thereby allows conceptualist as well as predominantly visual artworks. Rauschenberg’s prime Combines stick in the mind; they surprise and keep on surprising.

Alas, not many of the Combine paintings are particularly “photogenic.” But they do that picture-plane trick that critic Rosalind Krauss tries to talk about in her essay for the 1997 Guggenheim retrospective, making Rauschenberg seem like a latter-day Hans Hofmann determined not to violate the picture-plane. She was right. He respects the picture plane, but by putting things in front of it.

The art criticism consensus has been that, no matter how much one might be attracted to this or that silk-screen painting or technological folly, the Combines are Rauschenberg’s highest achievement, so I was excited about seeing a big batch of Combines all together. But the first thing I learned as I walked through is that Rauschenberg was as indiscriminate in his Combines as he was with his silk-screen paintings. However, when he hits with the Combines, he hits with a big bang. Maybe this is why we should not dismiss the silk-screen paintings, or the technological works, just yet.

Has anyone ever counted how many really boring or uninspired paintings Picasso made? Like Picasso, Rauschenberg has been an art machine; just keep the wheels rolling and sooner or later inspiration will strike. And it will probably take others to tell you when it’s really happened. How unlike the Duchampian constipation-mode of creation. Another rule for art: You gotta have product; lots and lots of things to sell.

And then it dawns on you that the curatorial lack of discrimination mirrors Rauschenberg’s own system. This is not good. The current exhibitionis an awfully expensive way of finding out that the Combines do not form a consistent body of work. But given Rauschenberg’s wild manner of making art, should we have expected otherwise?

When confronted by so manyCombines all thrown together, the majority being more-or-less flat, the tiniest of squints will reveal that what you are really looking at is outsized Late Cubism. After all, assemblage is an offshoot of collage. But then you have to ask yourself, is Cubism wrong?

Rauschenberg’s Combines and silk-screen paintings areas faceted as classic Cubism, presenting multiple points of views — not of one still-life, but of life itself, through the use of photos, words, objects of differing scales and degrees of detail. There is no bowl of apples, no face, no café wine bottle, no pipe you need to decipher. It is perception itself (and its intermediaries) you need to read.

It may be too soon to judge Rauschenberg’s silk-screen paintings, but I am not reluctant to announce that the all-white paintings of 1951, the 22-foot automobile-tire print of 1953, the erased de Kooning drawing of the same year, the Combines mentioned above, plus Factum I and II of 1957 (in which Rauschenberg duplicates a spontaneous Combine painting) are great artworks worth seeing and thinking about. Of the technological works, I’d vote for Soundings of 1968, and Mud Muse of ’68-’71. And I am not the only one to think that the cardboard box wall-pieces will look better and better as the years go on.

But Rauschenberg’s most lasting contribution may be his nerve. All-white paintings? You bet. Stuffed birds? Why not. Performances? Of course. Art and technology? Sure. He has never been embarrassed by his own lack of decorum.

* * *

To repeat the rules, you have to produce icons and you gotta have product; lots of it. But to become a successful artist, it also helps to invent a new term — like Found Art, mobile, or Combine. Furthermore, you are required to produce at least one good quote, like Rauschenberg: “Painting relates to both art and life. Neither can be made (I try to act in that gap between the two).”

FORE-MAIL ARTOPIA ALERT WHEN A NEW ESSAY IS POSTED CONTACT: perreault@aol.com