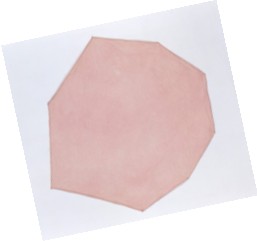

Richard Tuttle: Purple Octagonal, 1967

Richard Subtle

“To make something which looks like itself is the problem, the solution.”

Richard Tuttle

The new Richard Tuttle retrospective, initiated by SFMOMA and now at the Whitney (945 Madison Avenue, to Feb. 5), opens old wounds. But a rehash of yesterday’s art rages is instructive in outlining how hierarchies function, how blame is apportioned, and how custom impinges upon artistic innovation. Essays in the current catalogue gingerly brush against bristles once raised.

An extremely negative review in the New York Times concerning the first Richard Tuttle exhibition at the Whitney Museum in 1975 seems to have had a lot to do with (1) curator Marsha Tucker being asked to resign and (2) Tuttle’s eventual fame. Tucker, whom I remember swearing she would never focus on aesthetics again, went on to found the New Museum. On a new DVD called Richard Tuttle: Never Not An Artist (dir: Chris Maybach for Twelve Films), Tucker claims her departure was the best thing that ever happened to her. It’s doubtful that the Whitney would have produced “Bad Painting,” “Bad Girls,” and the first Ana Mendieta retrospective (with yours truly as co-curator), all New Museum exhibitions of some importance.

Please note that it was not the director who was forced out of the Whitney, nor was it the chairman of the exhibition committee, nor, heaven forbid, the chairman of the board of directors. Although the Tuttle exhibition in retrospect was a brilliant experiment, someone in the museum hierarchy was asleep at the wheel. Who was in charge? Or was it simply that Tucker had not prepared her bosses for the exhibition? Why did anyone worry about an attack in the New York Times, by Hilton Kramer? Nowadays an attack by him is as good as praise.

Or, as my old friend the dance critic Edwin Denby told me when I myself was attacked by Kramer, just measure the column inches. That’s what counts. Every dancer knows this. Kramer had called me avuncular, which struck me as odd, since at the time I had hair like a lion’s mane and was routinely called “Jesus” by truck-drivers. To make matters worse, Kramer had misspelled my name. Oh, the pity of it.

Tuttle went on to become an art hero, all in the name of beauty. Kramer eventually moved from The Times to the New York Observer, a venue more suitable to his bent and where, although still foaming at the mouth and whether one disagrees with him or not, he can do less damage.

Richard Tuttle: Purple Octagonal, 1967

Breaking the Rules

In regards to the 1975 Tuttle show, even Lawrence Alloway in The Nation went after the jugular — Tucker’s. What caused all the ruckus?

Believe it or not, for Alloway the problem was that there was no catalogue for the opening. He had no difficulty with Tuttle (after all, the artist’s dealer was a close friend, about whom he had been commissioned to write a biography). Was there a Tucker vendetta of some sort?

The exhibition was to be changed by the artist three times during the course of its run, so a catalogue to document these events had to wait until the end. Tucker, who had co-curated the Whitney’s “Anti-Illusion” show in 1969, was no stranger to site-specific, process art. And neither were we. For that show I remember that Rafael Ferrer dumped autumn leaves and blocks of ice on the Whitney entrance ramp. Robert Morris’s Continuous Project to be Altered Daily also debuted that year in a warehouse rented by his dealer, Leo Castelli.

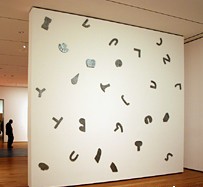

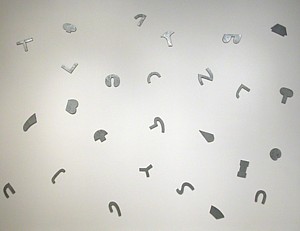

For Tuttle’s 1975 retrospective, the artist himself had almost total say in the installation, but then again, many of the works required this and were about installation. General art-height was determined as an inch or so lower than art industry standards: 54″, like light switches. But some tiny works were daringly placed where a baseboard might be. And some were on the wall, and then in the next installment spread out on the floor. Sometimes top-and-bottom orientation — as in the signature, Tintex-soaked canvas “Octagons” — had to be improvised. And his still delicately beautiful “Wire Pieces” needed to be made on the spot, as did a room of string-drawings laid out on the floor (not in current exhibition).

Installation was, and is, all-important to Tuttle. A big empty wall or a floor is the ground for his 3-D doodles, his hand-held, hand-made assemblages, his disconcerting, apparently off-hand sculpture/painting/drawings. He had, after all, started in the art world with a day job as the gallery assistant, backstage installation-guy at the prestigious Betty Parsons Gallery (where Jackson Pollock had shown and where Ad Reinhardt, Tony Smith, and Barnett Newman were then still in the stable). Tuttle’s focus on presentation was inherited from or inspired by his gainful employment. It was there at Parsons that Tuttle had his first solo exhibition in 1965, which is a little bit like a Warner Brothers usher getting to fill in for the song-and-dance man on the mend and turning into Dick Powell.

What? Let the artist do his own museum installation? Dicey, at best. A post-exhibition catalogue? Still unusual now. We need those catalogue essays, no matter how badly written, to write our review or, as laypersons, misguide us through the exhibitions. Both “innovations” signaled a break-down in museum protocol – i.e., territory and control.

Richard Tuttle: Purple Octagonal, 1967

A Threat to the Art Supply Industry?

To make matters worse, a lot of the works were made of bits and pieces of what would normally be studio debris, little bits of nothing anchoring big expanses of formerly inarticulate, all-white museum wall space. String, wire, fluff. But didn’t Kramer get the charm of these strategies, or at least understand the precedents? Had Kurt Schwitters lived in vain? Although even then Tuttle was understood in the art world as being — albeit perhaps too mystical and too poetic — an important part of what would be soon valorized as postminimalism, Mr. Kramer seemed to be obsessed with the reductiveness of Tuttle’s scale, which to my mind was — and still is — heroic in its displacement of the bigger-is-always-better American cliché. Tiny does not necessarily mean twee. But I am still not sure we have learned that yet.

As it turns out, Tuttle, in spite of some bad press, went on making art and, as the current exhibition proves, most of it is quite good: loopy, tender, deceptively modest. At this point, his triumphant retrospective is the one museum exhibition in New York not to be missed. Delight without cheap sentiment is not easy to find.

Guess what. After 1975, the art world was not destroyed. Not all artists suddenly demanded to install their exhibitions — some, in fact, understood they were better off leaving it to the experts. One of my fantasy student assignments has always been to require the installation of a group of art masterpieces so that they look really, really dreadful. The assignment is far too easy: wrong lighting, wrong spacing, wrong placing. Even inappropriate framing can ruin the best of paintings. It all hangs within an inch of disaster.

Furthermore, after latrines, sponges, dead hares, and little bits of cloth and bubble-wrap, we now allow dung, sharks in formaldehyde, gingerbread, and any number of post-Dadaist/Fluxus, postminimalist nonart materials. Nevertheless, the art-supply industry is as strong as ever. Tubes of oil paint and acrylic still outsell chocolate syrup (re: Vik Muniz currently at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia to Nov. 27) and toothpaste (murals by yours truly) as art materials.

Richard Tuttle: Purple Octagonal, 1967

Did He Really Say That?

Other Tuttle problems are less easily solved: his mysticism (since mysticism is still a no-no unless you are in Europe or California) and his tendency to offer gnomic statements.

Although his assertions that his work is an effort to overcome identity, and that “The job of the artist is to come up with ideas of how the mystic can be accommodated” might be puzzling to those not spiritually inclined, exhibition organizer Madeleine Grynsztejn also quotes him more productively in her excellent catalogue essay:

The main subject of my work is this kind of perfection, it’s an experience I’ve had, it’s a kind of metaphysical, or maybe someone else could say a ‘mystical’ experience that’s happened, say, three times or four times in my life and I would like it to happen everyday and I would like to be able to make a picture or a sculpture where other people can have that experience because when you have that it also clears the mind.

All of this would sound less scary if recast as what once-trendy psychologist Abraham Maslow called “peak-experiences.” Maslow in the ’60s had the brilliant idea of studying healthy people for a change and found, he claimed, that they were all mystics, or at least had experiences of unity and transcendence that, to soften the blow, he called peak-experiences: Religions, Values and Peak-Experiences (1964) and Toward a Psychology of Being (1968).

Aside from mysticism, is Tuttle’s art (as Tucker seemed to have concluded) only about aesthetics? Even a stick or a wire tells a story. There is also the language-as-subject problem. To some degree, Tuttle has been producing alternate alphabets. Letters of 1966 is even composed of 26 discrete forms to produce a constellation of forms you can almost but not quite read. The same may be said for most of the Tuttle “runs,” such as the “Octagons,” the “Wire Drawings” and even the framed drawings of various sorts in a series or as exemplifications of theme-and-variations. Can all these “letters” be combined in different ways, as in scholar Moshe Idel’s rediscovered ecstatic Kabbalah, to yield fresh meanings? Given five materials or five “letters,” how many words can the permutations spell?

The alphabet has always been important to me. In the late ’60s I did a number of performances structured by it; one, as it turns out, at the Whitney. Although as a child I could read before going to school, I had trouble memorizing the alphabet. It was, I felt, not my alphabet, not my language. Tuttle’s alphabets are also not mine, but I can hear what they say. They say that Nothing – let’s say a couple of inches of rope nailed to a wall – can be huge, that the ordinary can be sublime.