The Dead Are Dumb

New age beliefs have made the notion of contacting the dead quaint rather than bizarre. Once upon a time photography was thought capable of offering proof of spooks. Hence the charm of “The Perfect Medium: Photography and the Occult” at theMetropolitan Museum of Art, N.Y.C.(through Dec.31); and, as they say, it’s packing them in. On the surface the exhibition is more sociological thanaesthetic, since it documents the 19th and early 20th century rage for spirit photography, here and abroad.

Visitors are clustered so deep in front of each vintage photo that one can hardly glimpse the ghosts. One way to go is to seek refuge in the catalogue, weighing in at a steep $65, but available for perusal in a convenient nook. Fine with me. Except for the large blow-ups now in fashion, I have never seen a photograph on a wall that did not look better in a book. It is the thinness of the image that makes it real. You can feel it between your forefinger and thumb. Leafing aids looking, and provides the tactility that photographs lack.

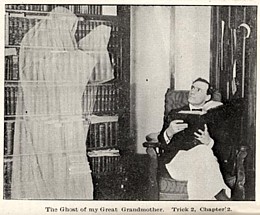

Why was there once this flowering of photo-fraud, as demonstrated by “The Perfect Medium?” The general theory is that spiritualism, at least in the U.S., was accelerated by Civil War grief. Johnny was never going to come home. Table-tapping, already established among the vulnerable, yielded to trance-mediums summoning Johnny and other apparitions that could ease the pain and anger. Furthermore, if the dead could talk then we could be privy to the secrets of the afterlife and of future events. This never turned out exactly to be the case. It took awhile for it to set in that death did not make Johnny or Grandma any smarter than when alive. Now we have the folk-trope that the dead don’t know they’re dead, which is why they keep hanging around. Be gone dumb spirits!

Since it was all about lenses, glass plates, and chemicals, photography was scientific. If you could photograph a spirit you could prove life after death and life itself would be less appalling, merely a kind of rehearsal for a new life in which one could run around clad in sheets. You could also evade a good deal of responsibility in the here-and-now.

Now we have channeling, not of the dead but of higher entities with urgent messages, sometimes complex but always banal. Love is the answer, and has been since about 1890. The new age is old. Scholars now deduce that we can credit the late 19th century turn from spiritualism to occultism to Theosophy’s Madam Blavatsky, to the British spirit-chaser Emma Hardinge Britten, and, to my mind, most importantly to the black, American sex-magician Paschal Beverly Randolph, whose weird and wonderful autobiographical novel called The Wonderful Story of Ravalette you can actually read on line. He was born in Gotham’s notorious Five Corners, had audiences with kings, thought women should have pleasure in sex, and trafficked in cocaine and semen-smeared skrying mirrors.

All three luminaries exhibited youthful traces of mediumship, but each in his or her own way outgrew that talent and moved spiritualism to occultism. Occultism, as opposed to spiritualism, is overtly Self-centered. Everyone can become his or her own medium and you don’t need someone else to summon spirits who might provide mystic truths. Least we forget, even the Elizabethan sage John Dee needed thumb-less thief Edward Kelly to be his medium. Suddenly in the spirit of Andrew Carnegie (and Randolph) you could do it yourself. And, like the sagacious Dee, who was an advisor to Queen Elizabeth and a model for Shakespeare’s Prospero, we wanted angel advisors, not some dead Civil War soldier or Grandma speaking from beyond the grave.

Spirit Photo:

Eugene Thiebault: Henri Robin and Specter

Poetry in Gauze

We now find it poignant that our ancestors could have been fooled by double-exposures, actors in tights, and gauze — tons of gauze — coming out of the mouth’s of mediums, hovering, bolts of ectoplasm floating here and there. Gauze of course is used in bandaging so perhaps there was an inadvertent metaphor involved.

I suspect that the popularity of this exhibition has to do with 9/11, Katrina, Iraq, and other catastrophes. Add here this week’s earthquake in Pakistan. Life again no longer makes sense. Or, as a simpler explanation, is this unexpected crowd-pleaser an illustration of the constant need to feel superior to our ancestors? How could they be tricked so easily? Was photography that trusted? We know better now, don’t we? And yet we are easily fooled by charts and maps purportedly showing factories producing weapons of mass destruction.

And aesthetics? Because of the universal acceptance of set-up photography and because Photoshop and other digital image-altering tools allow even amateurs to amend images at will, we should no longer trust photography. It is a fiction. So spirit photography, primitive as it was is the ancestor of contemporary photographic practice.

The notion that photography can be fool-proof, that the visual is necessarily evidence for the invisible is indeed naive. But it is not witty. Ghosts are rarely seen and when seen are glimpsed slightly out of the range of direct vision or quickly in mirrors. Find me the apparatus that can photograph a scent, or a sudden drop in temperature. Or a poignant memory. Or hope.

For more ghosts, please visit my recent column called “Ghosts of Staten Island.”

Archive at upperright, to September, scroll down to September 6.

As a service to loyal readers, Artopia can now offer notification of new installments of John Perreault’s Art Diary as they are made available. If you should desire an Artopia Alert, please send an e-mail to that effect to perreault@aol.com.