The Past Is Another Place

I could tell it was going to be one of those adventures. Sylvia Sleigh, a painter I’ve known for many years, phoned me about going to the opera this fall. Sylvia at 89 goes to the opera a lot. Her late husband, the art critic Lawrence Alloway, had hated opera, so she is making up for lost time. I hated opera queens more than I hated opera. I simply could not get interested in the eternal question of who is greater, Callas or Tebaldi? I think Schwarzkopf is greater than both; and as for tenors, I prefer counter-tenors.

But then one thing led to another, and I apologized to Sylvia for not having seen her show at Snug Harbor yet. Well, she said, Nancy and Arlene are driving me over to Staten Island. I need to take some pictures, and they haven’t seen the show yet either.

When,I asked?

Tomorrow!

Was there room for me?

Even though I took the R to Battery Park, the ferry and then the bus for four years when I was visual arts director at Snug Harbor Cultural Center, in this day and age, particularly in the deadly, gloomy, global-warming heat, Staten Island seemed far away indeed. So I jumped at the chance. Besides, I had not seen Arlene Raven and Nancy Grossman for quite awhile. When was it that they had moved to the depths of Brooklyn? But I seem to have known them forever. Raven is an important feminist art critic and historian; Grossman is celebrated for her leather heads, which some find disconcerting, particularly since one appeared to have been on the premises of a particularly gruesome art-world crime scene. Never mind about that, to me they have always seemed more about personal anguish and anger than about bondage.

The next day the two gals from Brooklyn pulled up at Sleigh’s Chelsea brownstone in a huge, late model BMW. Black, of course. Tiny, talkative Grossman was at the wheel, and we gabbed our way to the Battery Park Tunnel, the Verazzano Bridge and all around Bay Street to Snug. Sleigh held forth too. And Raven, also in the back seat, had many requests for more ventilation, or less. The air conditioner was, even when on, doing weird things.

It was a good thing I had come along; Grossman had left the driving instructions, concocted by Sleigh’s studio assistant, back home in Brooklyn in their converted lumberyard. Both Sleigh and Raven were disappointed at the lack of car-carrying ferries. One more romantic thing about New York has bit the dust. Was it in the name of efficiency or 9/11 security concerns? Commodore Vanderbilt probably never thought his ferries would be carrying horseless carriages; he (as once explained to me by one of his descendents) started his fortune by hauling manure from Staten Island in a rowboat.

Nevertheless, the ferry fare had been cheap. The Verazzano Bridge is enormously expensive: $9.50. And you had better have a EZ pass, because you will never make it across the Verazzano toll plaza to the two lonely cash booths. Fortunately they were on the same side of the toll plaza as our Bay Street exit.

There is indeed another, quicker non-Bay Street way to get to Snug Harbor, but it involves mysterious turn-offs and the ever-present threat of ending up in New Jersey, where the Meadowlands presents a no-man’s-land automobile vortex. Or at least that’s how it appears to Manhattanites. Staten Island is in New York City, isn’t it? It is treated so badly by New York City government agencies that you sometimes wonder. It is the pot-hole capital of the world, and there is the slight problem of the Fresh Kills dump.

Sylvia was wide awake, and having adjusted her hearing aid, was again holding forth, as was Arlene. As was Nancy.

Silence, I demanded. If, as navigator, I can’t concentrate, we’ll end up in New Jersey!

Our route around the tip of S. I. on Bay Street was foolproof, but unfortunately presented a grim picture of the island that, artwise, used to be mine. We did not traverse the Green Belt, nor did we even glimpse Lighthouse Hill (where the Jacque Marché Museum of Tibetan Art perches just up the street from a Frank Lloyd Wright Usonian abode. Or mysterious Todt Hill, with its rock-star mansions and spectacular Cinemascope views of New York Harbor.

We did see the sign for the Alice Austin House. Since the Snug Harbor galleries would be closing in an hour and a half, we didn’t have time for this charming, shoreline house museum. Alice Austin House is named in honor of a pioneer woman photographer, and, if we are to believe some of her snapshots,habitual instigator of rampant, larky cross-dressing on the part of her many women friends. After all, opined Raven, the two serious ladies of Jane Bowles’ novel of that same name lived in Staten Island, didn’t they?

But I did point out a sealed 1920s movie theater, no doubt now a live-mold and harbor-rat museum; and a charming park once popularly known as St. George’s very own Needle Park. And then the odd-looking Yankee’s ballpark. The Yankees! shouted Grossman.

According to Sleigh, painter Craig Manister (co-curator with painter Cynthia Mailman) suggested that everyone should enter through the front door of the Main Hall (Building C) at Snug Harbor. The cornerstone was laid in 1831, opened to the Snugs and staff in 1833. And so, according to some, was inaugurated the first nonreligious charitable institution in the U.S.

I guessed Manister wanted everyone to see the Main Hall. I myself know it by heart. I had my office there; that office was once Thomas Melville’s when he was president of Sailors’ Snug Harbor from1867 to1884. And now it is a gift shop. Oh, the indignity of it: not one of my great-great literary uncle Herman’s books for sale! Not one of his great-great nephew’s exhibition catalogs. And none of his recent seascapes, either.

Everything in the 1831 Main Hall is cleaned up now. No peeling paint. But tears came to my eyes when I saw the marble mantle in my old office. I could look out on the founder’s obelisk, really a grave marker, for he is buried beneath it, apparently standing up: Captain Robert Richard Randall; c. 1750-d. 1801.

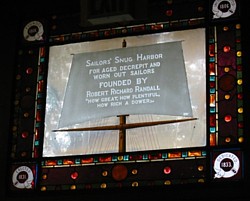

I could still hear the honorific toots from passing freighters and tugboats in the Kill Van Kull just across Richmond Terrace, running between Staten Island and Bayonne. Sailors’ Snug Harbor was founded and maintained for the benefit of “aged decrepit and worn out sailors” as the stained glass window over the entrance says. The inscription is read from the inside, by the way, no doubt to remind the Harbor’s indigent charges of Randall’s or perhaps the Trustees’ magnificent beneficence: three square meals, and two seamen to a room. Alcohol forbidden.

In this century, the institution was called to task by city health officials for the Harbor menus; the city had to withdraw when it was shown that retired seamen hated salads and raw vegetables and routinely dumped them under the table.

I have seen a reprint of a list of “taboos.” This was Captain Tom Melville’s term, no doubt borrowed from his brother Herman, who was famous for his fictionalized adventures in the Marquesas in a book called Typee. Furthermore, if you came back drunk from the off-grounds saloon, you would be “tabooed” and confined to your room for several days.

All “aged decrepit and warn-out sailors” were accepted. Even some blacks. Eventually the Harbor also allowed steamboat sailors and inland sailors from lakes and rivers too, but they were no doubt frowned upon as not being adventurous enough. Once, while trying to affix a sculpture to one of the walls, we found a sealed-offcompartment containing a book of photographs of hundreds of inmates (as the retired seamen were called). Here and there were some dark faces. All races and nationalities were welcomed. Only “habitual alcoholics and those with contagious disease or immoral character were banned.” Does the latter mean those who have sex with other men?

The Main Hall, a prime example of Greek Revival architecture,is now a visitor’s center and currently also showcases some artworks from the S.I. Institute of Art (which will eventually open additional quarters in Building A and B.) Look at the dome above. Note the nautical decorations and inscriptions and stained glass over the doorways. There’s a beautiful crescent moon. But I know a secret.

Behind the sunburst at the front of the dome is a small room lined with tin and a movable mirror with which one can redirect the light from the skylight so that it blazes through the painted glass sunburst. The attic is in fact quite wonderful, for there, if you are luck enough to get a tour, you can see the shipbuilding joinery used to interlock the timber and quaint sailors’ graffiti scratched into the gigantic beams. We had trees then.When there was old forest left it was said that a squirrel could travel from the shores of New England to the Mississippi without ever touching the ground. And the stoneon the fronts of the buildings was floated down the Hudson from Sing-Sing quarry.

When I was there, the Main Hall was for showing art. Some of the installations I engineered were gigantic — a survey of the welded sculpture of Ann Sperry; hanging stones by Gillian Jagger; and a three-story wave of saplings by Patrick Dougherty that looped from the upper railings down to the floor.

* * *

Sleigh on Display

Now the Newhouse Center for Contemporary Art is confined to the building behind the Main Hall, where the dining rooms were. There our merry group contemplated Sleigh’s show “Portraits and Group Portraits” (through October 2). What would the old sailors have thought of all those male and female nudes? The males sometimes unashamedly frontal? Even today it was necessary to warn the public that two rooms have nudes displayed.

Or what would the sailors make of the fully clothed gang of women artists who make up A.I.R. Group Portrait (1988)? What are all these women doing together, besides staring us down? This is probably Sleigh’s best painting. A.I.R. is a pioneering women’s gallery, and she captures all the energy of that feisty, talented group. It complements or contrasts with The Situation Group (1961), a painting Sleigh did of the mostly male British Pop group — which included Alloway, her husband, who coined the term Pop Art.

Sleigh liked the way her paintings look against the warm white of the rooms. I was there when the Snug Harbor resident architect chose it: Benjamin Moore Antique White. So much better than MOMA stark white, says Sleigh. But I think her paintings might have looked even better in the Main Hall: her patterned backgrounds wilder against the Victorian moldings and the ornate nautical décor.

Arlene Raven’s catalog proem, “In the Details; Sunday with Sylvia,” outlines how it felt to be painted, hyperactive Nancy hovering over her, while slumped in reverie. Most relevant here, however, is the quote from Sleigh:

“Even if I paint a leaf, it should be a portrait. If we could all appreciate every living thing in detail, we would be kinder and better to one another. “

I’ve been painted many times by Sleigh — once famously in the buff, added to a room of other naked art critics — but not in the current sampling. Here there’s a picnic painting that treats me kindly, as does a preliminary drawing for her Invitation to the Voyage, which I once showed in the Snug Harbor Main Hall as part of an exhibition I called “Eminent Immigrants” in 1986.

* * *

Ghosts I Have Known

1. Building ghosts:

The Snug Harbor Cathedral, caught mid-wrecking-ball in a photograph in the Staten Island Advance; the panopticon Sung Harbor Hospital. On foggy nights, they reappear.

2. Ghosts of ships:

Thomas Randall’s pirate ships: Charming Sally and Le Jeune Babe. If I had a boat, even just to cross the Great South Bay from Bellport to Ho-Hum Beach on Fire Island, I’d name it the latter, wouldn’t you? And if you could use male names for vessels, I’d name it Captain Randall.

3.More ghosts of exhibitions past:

David Finn’s masked, garbage figures in the C-E Hyphen. Judy Chicago’s “Birth Project”; Beth Swartz’s “Moving Point of Balance.” “The Sculpture of Elizabeth Egbert ” (indoors and outdoors)….Currently art spaces and museums can barely produce one exhibition every six months, I installed one every month. But that was the ’80s.

4. Imaginary ghosts:

The front buildings are connected to each other and to the building in the back row by architectural “hyphens” or first-floor enclosed passageways so, I suppose, the “inmates” would not have to deal with the elements. In the basement of the building behind Main Hall, right where it connects to theC to E hyphen, there is a ghost: a priest clubbed to death by an angry sailor.

5. And yet another ghost:

When I was on board at Snug Harbor, the Matron’s House (directly behind the showplace buildings) was used for artist studios, and several of my friends reported hearing footsteps. My assistant Charlie, who had a studio in another building,saw a woman in Victorian clothes looking out a window on the second floor of the Matron’s House. Legend had it that her illegitimate child had been still-born and she had never recovered, even after death, from this tragedy.

6. Mad ghosts and dream ghosts:

Even the still-living can generate ghosts, as can the never-having-really-lived.

Artist Jane Greengold, under my reign, had turned one of the Main Hall rooms into a replica of a sailor’s bedroom and then depicted that sailor’s dream in another room in the cellar of the D Building next door. If you peeked through the window, you could see chaos and depictions of rushing seawater. We suspected that the mad guard, a frustrated artist, had taken a match to the painted waves. There was no proof and it was for threatening behavior that he was carted away in a straight-jacket, leaving behind his forever angry ghost.

And there is also the ghost of Greengold’s fictional sailor, so vividly brought to life by “his” bedroom and “his” dream.

7. Richard Randall’s ghosts:

Of course, bachelor Randall, son of an infamous privateer (i.e. legally sanctioned pirate) left several ghosts behind. The legend is that Alexander Hamilton, a friend, announces that ” it came from the sea, so let it go back to the sea.” What came from the sea was Randall’s family fortune. Seamen then had no social security or retirement accounts, so Richard on his deathbed wanted to step in.

Randall was long gone when Snug Harbor finally opened on Staten Island; but his corpse was moved from Trinity Church cemetery to soil he had never walked on. Local legend has it that he walks at night, trying to get back to Manhattan. Does his ghost know there’s nothing but apartment houses and a K-mart where he once lived in an octagonal building on his 21 acre Minto farm? It was the subdivisions of that farm that provided the money for Sailors’ Snug Harbor.

Then too the present bronze statue of Randall, now surrounded by garish Victorian plantings, is only a replica of the one made by Augustus Saint Gaudens in 1878. Where is the original? Sailors’ Snug supposedly took it down to Sea Level N.C. when they moved after New York city bought all 80 acres and the surviving 24 buildings in 1978. But is it still there? The statue, overlooking the Kill Van Kull, is a bronze ghost. Art works too can leave ghosts behind.

I am sure Randall has several other ghostly manifestations haunting the descendents of the various trustees of Randall’s, who profiteered upon his estate.In Manhattan it stretched from what is nowWaverly Place to 10th Street and from Fifth Avenue to Fourth Avenue. Look at your Lower Manhattan map. Not exactly what you would call cheap land. Well-placed politically and with Albany links, the Randall trustees — you know who you are, you long-dead mayors and ministers, you creeps — kept changing the rules as the city marched north, until Staten Island became the solution. Put the sailors there, and let’s get on with filling in the Manhattan grid. And then there is the expatriate Tory, John Ingles, the Bishop of Nova Scotia, who contested Randall’s will from abroad to make some point or another about Tory rights. Or for cash.

8. Entertaining ghosts:

Snug Harbor, now more correctly called Snug Harbor Cultural Center, is full of ghosts. There are the ghosts of all the performers that entertained the sailors in the Music Hall. Did the notorious actor Edwin Forrest play there? He who was once described as “as a vast animal bewildered by a grain of genius”? Did Edwin Booth? Did the operatic Jenny Lind? And I’d like to know too what movies were shown to the sailors, beginning in 1911? And now there’s probably a ghost of the three-inch thick mold I saw covering all the seats of this once gas-lit theater when it was unsealed for restoration. There were also individual earphones in the vast Library/Recreation Hall, so that Snugs could listen to broadcasts undisturbed. Does the music from those broadcasts linger? And are there ghosts of the Stickley chairs and desks, stolen between regimes, long gone?

9. My ghosts:

And I have added some ghosts of my own. A living person can have a ghost. I am in that old front office of mine, selling souvenirs, writing poems between each transaction. But above all I am in the concealed tin room high above in the dome, moving the mirror.

* * *

Recommended:

Barnett Shepherd, Sailors’ Snug Harbor: 1801-1976, Snug Harbor, 1979.

(Shepherd proves that the Main Hall architect was Minard Lefever, famous for his Greek Revival pattern books: The Modern Builder’s Guide and The Beauties of Modern Architecture.)

Gerald J. Barry, The Sailors’ Snug Harbor, A History, 1801-2001, Fordham Press, 2000.

(Barry reveals that Thomas Melville, although investigated and called to the carpet for his irregular purchasing policies, was never actually prosecuted for embezzlement.)

–