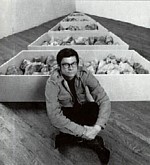

Robert Smithson (1938-1973), c. 1968

Once you have approached the mountains of cases in order to mine the books from them

and bring them to the light of day—or rather of night—what memories crowd in uponyou!— “Unpacking My Library” in Illuminations, Walter Benjamin

By The Book

To my mind, the most interesting aspect of the catalog for the Robert Smithson retrospective (now at the Whitney) is the book-by-book, magazine-by-magazine, record-by-record record of the artist’s library, compiled by Valentin Tatransky.

This is not because my 1969 book of poems Luck (Kulchur Press) is listed — did I give it to him, or did he buy a copy when I had that autograph party at the Gotham Book Shop?

No, I like the catalogue of Smithson’s library because it reminds me how well-read and intellectually curious he was. Unlike some of the Ivy League minimalists, Smithson was a true intellectual. But perhaps this was because he was self-educated. Too many now evince amazement that Smithson escaped so-called higher education: he was so smart, so informed and such a good writer.

Alexander Alberro’s little essay, “The Catalogue of Robert Smithson’s Library” points out some oddities among the 1,000 or so items that Smithson left behind: No copies of Artforum! Maybe Smithson had copies in his filing cabinet of his own essays that had been published there, and perhaps he had no interest in re-reading Annette Michelson or Michael Fried. Yet there is also no copy of J. G. Ballard’s The Crystal World. To whom had he loaned it? The mystery of the inclusion of L. Ron Hubbard’s Dianetics, along with Georges Bataille and Claude Levi-Strauss, is really no mystery at all if you remember Smithson’s love of science fiction and Hubbard’s “humble” beginnings as a pulp sci-fi success.

Here are some books in Smithson’s library that were surprising: William Rubin’s Modern Sacred Art and the Church of Assy; Owen Barfield’s Poetic Diction: A Study in Meaning; Raynor Heppenstall’s Leon Bloy; Mao Tse-Tung on Literature and Art; Literary Criticism of Alexander Pope. I was surprised not to find anything by his friend Hubert Selby (Last Exit in Brooklyn) and at the absence of William Carlos Williams’ Paterson (although Kora in Hell was there). Williams was Smithson’s baby doctor, and Paterson is the industrial neighbor of Clifton where the artist grew up.

But we are certainly are not surprised by the Bhagavad-Gita, The Book of the Dead, Edmund Husserl’s Ideas, Hannah Arendt’s On Violence, or Illuminations, Hannah Arendt’s anthology of writings by Walter Benjamin. Nor that in his record collection, Country Joe and the Fish and Marlene Dietrich are somehow in the same audio universe as motets by Francois Couperin.

Predictably and sadly, Alberro cannot resist stating about Smithson’s library “That an artist with no formal academic training compiled it is astonishing.” More astonishing to me is that artists with “formal academic training” nowadays have no libraries at all.

When I make studio visits, I no longer wonder where all the books are. I know there are none. This started around 1974. Since I am really Candide in disguise, I used to think book-free studios were just an attempt at elegance. What purity. The artist did not want me to be distracted by piles of reading material. They themselves did not want to be pulled from their easels by James Joyce or Martin Heidegger. Or Hart Crane. All the books, I used to think, must be hidden away in the bedroom. Since I read voraciously, I thought all artists did.

Now I just accept it; artist’s don’t read. I am not sure if it’s because they don’t like to read, or they just can’t read. I hate to think that visual creativity is just compensation for illiteracy. Perhaps art schools and college and university art departments have also fallen to what Jane Jacobs, that lovable scold, calls “certification” as opposed to “education” in her new book, cheerfully titled Dark Age Ahead.

But I can imagine something else. The artists are getting all their information through the internet.

Well, not yet. Many more books have to be scanned.

* * *

John Perreault. (detail) Bookwork, 2003

All Booked Up

These musings lead me to think about my own library, presently numbering around 4000. In the 1940s, when the notorious Collyer brothers were disinterred from the 180 tons of junk they had amassed, the NYPD not only discovered 14 grand pianos, two organs, a clavier, six tons of old newspapers, and the chassis of a Model T Ford, they found a library of 14,000 engineering and medical books. As far as I can determine, neither brother was an engineer or a doctor.

Occasionally the ghost of my sainted mother visits. She wags her finger and accuses me again, as when I was a teenager, of being a Collyer brother. She never understood how important to me were my father’s African souvenirs, or my small collection of turtle shells. She could not distinguish between collecting and hoarding. The Collyer brothers hoarded. They never played their 14 grand pianos. I use my 4000 books — at least potentially — and they are more or less well-ordered.

They do add up.

Just yesterday I estimated I had at least 1200 books in my tiny East Village apartment. My Long Island hideout has a 14-foot-high wall of jam-packed book shelves; I need a ladder to get to the top four shelves, which function as deep storage. There’s also the four shelves of books (and piles too) in the closed-in carport.

I am not boasting. I know a pair of dance critics whose commingled libraries take up all the wall space in their rather large West Village apartment: floor to ceiling, corner to corner in all the rooms, including the two bathrooms and the kitchen.

My books also just keep on accumulated. Like most bibliophiles, periodically I try to weed them out, but after days of making try-to-sell and just-throw-out piles, both piles miraculously start shrinking, and all but two or three books go back to their designated shelves, for from out of nowhere I am reminded of the Law of Books: Any volume that I get rid of absolutely will be needed within two weeks time, will have gone out of print, and will alone house that one juicy quote I think I need to clinch one argument or another or make my text more vivid.

Finally, the two or three orphans go back home too, because you never know when they will be irreplaceable and sorely missed. The Folk Toys of Uzbekistan? Will be worth hundreds of dollars on e-Bay. The Blood Sport Marble Tournaments of Maine? Gotta stay.

The Book Devil has spoken.

* * *

Hart Crane (1899-1932)

Amusing Problems of Bi-location and Retrieval

Before Long Island, I kept most of my books in a self-storage warehouse near the West Side Highway. Not having a formal cataloging system, I relied on the self-evident fact that whatever wasn’t in my East Village jewel-box was crosstown, and I took a bus — with my fingers crossed.

Now, through some strange law of geographical and bibliographical displacement, even though I try to predict my needs by carting books back and forth, the book I want and need when I am writing in the city is always out in Long Island, and vice versa. Perhaps I should have duplicate books the way I have duplicate vitamins, grooming items, stashes of underwear and socks.

Or use the N.Y. Public Library, or the excellent little library in my Long Island village. But alas, there’s another Law of Books:

The book you want is never in the public library. It either doesn’t have it or it’s checked out — never mind the danger of gravy stains and, worse yet, marginalia. And underlining and highlighting, which in my book are all capital offenses.

In the worst-case scenario, if I am in Manhattan I can run down the stairs and out the door to Barnes and Noble, Shakespeare and Co. and the St. Mark’s Bookshop (which is not on St. Marks Place). Recently, neither B & N nor Shakespeare had a single copy of Hart Crane. Fortunately, St. Mark’s did. (Just now I googled Hart Crane and I am happy to report you can go to poemhunter.com and read eleven of his poems, including “At Melville’s Tomb,” the poem I was looking for.)

So my books keep accumulating: review copies, museum catalogs, artist monographs; philosophy, religion, landscape gardening, poetry, folk art, outsider art, film noir. They form a solid record of my needs and tastes, over time. Are they a burden?

A few years ago, a friend of mine thought he could store all his CDs on his new iPod and thus free up floor space in his CD-infested Brooklyn apartment. But then, after copying a few, he figured out that it would take him at least two lifetimes to copy his music library — leaving no time to buy new CDs.

Perhaps I can get a grant to have all my books scanned by some unemployed baseball team, and then I could go online to access my reading material wherever I am. Isn’t that the new dream? Books are messy dust-collectors. They take up wall space that could be better used to display paintings.

The Book Devil: “But don’t you love browsing? Leafing? Holding that nice object and turning pages? In libraries or bookstores, particularly used bookstores, don’t you love the serendipity of coming upon a book you never knew about before and just have to read, to own? Don’t you love solving the problem of how to arrange your own books?”

I have an acquaintance who once got fired from a small bookstore because he was caught arranging the books chromologically – by the color of their spines. I recently authored a new conceptual artwork (a detail shown above) by giving my beliefs concrete expression. In my shelves of alphabetized artist monographs, I melded craft artists with painters and sculptors: so Chihuly is near de Chirico; Beatrice Wood is not too far from Warhol; George Ohr is on the same shelf as Meret Oppenheim on the theory that they are all artists of one sort or another and shouldn’t be segregated into largely irrelevant categories.

Libraries are a way of thinking.

* * *

Richard Prince: Untitled (photograph of an advertisement).

The Future of the Book

Some bestseller wannabees are now offered as electronic books and audio files, as well as pokey tomes made out of dead trees. I don’t think I’d be comfortable reading an electronic book in the bathtub; and I am not sure I should listen to Kierkegaard while driving on the LIE. But I can’t imagine anyone collecting an electronic book or a sound file or that they will ever by worth anything on e-Bay.

Books will make you rich. As they are replaced by new media, they will increase in value. Furthermore, books are the best décor. They are better than paintings. They insulate, sound-proof and advertise.

Advertise?

They tell people who you are. And sometimes this is much better than Judy Holliday’s Gladys Clover billboard on Columbus Circle in It Could Happen to You (George Cukor, 1954). The movie was originally titled A Name for Herself.

I have always liked Richard Prince’s cowboys, artworks made by rephotographing ads, mostly for Marlboro cigarettes. Wasn’t one a billboard showing that emblematic cowboy?

So I was relieved to have my taste confirmed in an odd way by a low-info article in the “Style Section”of the Sunday Magazine of the New York Times last week. We learned that the Guggenheim Museum bought Prince’s art-stocked house upstate, but did not learn who paid for it. This purchase was not put in context of other museums that may have acquired similar artist digs, nor did we get a good look at the interior of the house or at much of Prince’s art.

What we did see, however, as a bold graphic device, almost as big as Prince’s face, a detail of the artist’s bookshelves showing the spines of the science-fiction masterpieces of Philip K. Dick (Valis and Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?/a.k.a. Bladerunner), not mentioned in the accompanying piece of puffery. Since I think Dick is a genius, my estimation of Prince’s talents as an artist increased.

Next entry: July 25