Last week, a well-attended memorial for Leon Golub (1922-2004) was held at Cooper-Union’s Great Hall (where Lincoln spoke). Personal talks and reminiscences were offered by Nancy Spero, the artist’s wife and a fine artist herself, as well as by Kiki Smith, the poet Clayton Eshleman, and many others. I was reminded of an appreciation I wrote for N.Y. Arts magazine in June of 2001 on the occasion of the artist’s retrospective at the Brooklyn Museum. I couldn’t find it online, so I thought I would insert it here, with only a few changes in tense.

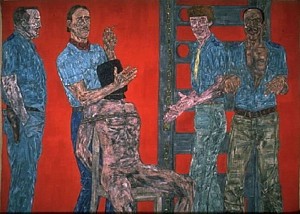

Leon Golub: Interrogation I, 1981

Mercenaries and Mad Dogs

Can we look at the paintings of Leon Golub with fresh eyes? Forget the kind of seeing that has to do with the postage-stamp reproductions in books and magazines. There’s an idea: Golub U.S. First Class stamps! When that day comes, rest assured it will have to be when war is over, when police states have been eliminated; when torture and terrorism have been abolished; when racism is no more.

But even if the reproductions of Golub’s masterpieces take up the whole page, you can’t get the sweep of his gargantuan paintings. Only in the biggest lecture halls or in an old-fashioned movie theater could you get slide projections anywhere near the size of something like Vietnam II, 1973, which is 40 feet wide. This is Cinemascope, or even Cinerama. This is the way movies used to be; this is the way of the Rivera or Orozco or Siquiros mural—bigger than any Pollock drip painting, bigger than Guernica (and I use these latter examples for a reason) and bigger than life.

In regard to my reference to Pollock and Picasso, any comparison to the former is a strange one, for Golub’s work, be that as it may, has no delicacy or mysticism, and his anger and angst is in your face; Pollock’s agony now seems to exist primarily in his biography and in sentences written by Tom Hess or Harold Rosenberg. One might be better off comparing Golub’s Vietnam paintings to Picasso’s Guernica. They have that kind of wrath.

And, as with the print replicas, something just as crucial as scale would be lost: texture. You can’t talk about the classic Golubs without remarking that they are on unstretched canvas hung on the wall, like circus banners, or that he scraped away at the paint with a meat cleaver. What you may not have thought of is that the lengths of unstretched canvas convey a sense of emergency that is compounded of urgency and despair. The Soldier of Fortune imagery is bad enough; the reality of the presentation and the execution is visceral. The empty zones in some of the big Mercenaries or Interrogation paintings, depending upon the pigments used, are fresh blood or dried blood. The jagged cutouts along some edges and even the irregularities of the elongated rectangles of these anti-flags further underline the sense of improvisation motivated by outrage at atrocities and abuses of power.

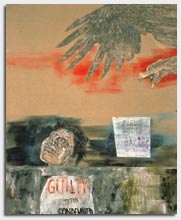

Prometheus II, 1998

I Am the Hero; I Am the Law

The exhibition of Golub’s work at the Brooklyn Museum of Art (2001) was one of those rare shows that anyone passionate about art could not afford to miss. The ambition, sadly lacking in much art, was there to behold: from his myth-inspired, paint-encrusted works done in Chicago early in his career, through his Greco-Roman period when he and Nancy Spero were expatriates living in Paris, through the Vietnam paintings begun when they moved to New York, and on down to the present.

Golub used the sign system of heroic art to make violently antiheroic paintings. He traveled from Greek tragedy to the tragedy of the banality of violence; from Oedipus to the ordinary Joe as both bound and gagged victim and assassin holding a gun to someone’s head. He, as we shall see, moved from the Sphinx and back. But up until the paintings of the last decade, everywhere there lurks the obscene suspicion that notions of the heroic are the root cause of a whole lot of trouble: I am the hero; I am the law; I kill and torture for a higher truth. But then one also thinks: My gun is for hire.

Can we see these works without readings? Try. Forget the Golub Brooklyn Museum retrospective catalogue quotes, e.g. “If I had to give a description of my work I would say it’s a definition of how power is demonstrated through the body and in human actions, and in our time, how power and stress and political and industrial powers are shown.”

Forget the thorough catalogue essay by curator Jon Bird, e.g., “To look and to be seen are not only issues of position and visibility, but historical and psychic processes embedded within social structures which contribute significantly to our cultural perceptions and evaluations.”

Forget the fey subtitle of the exhibition: “Echos of the Real.” In fact, before going to the exhibition, I gave myself the assignment of forgetting everything I have ever written about Golub. I am not sure I succeeded. When you write something–perhaps even when you read something–it seems to form a channel or a pathway that doesn’t go away. Let’s face it, there is no such thing as the naked eye.

Even Golub played with cultural and media memory: his image sources were ripped from “special” magazines and the headlines that have made us numb. In the mid-’70s he even perpetuated a whole series of political portraits: small head-shot paintings of Franco, Pinochet, Kissinger.

Nevertheless, during my first walk-through, when the preview hordes, black-clad and mostly gray-haired, had not yet swarmed into the official exhibition reception, I tried to imagine what a 20-something from Williamsburg might think. Given the state of art education and the lack of textbooks, no doubt he or she would not even have heard of Golub.

In several places there were comment books, a sure sign that someone is expecting negative reactions – and of course its better to let the yahoos blow off steam. As a curator, I have used this trick myself, only to realize that it encourages stupidity and/or sentimentality. I took a deep breath and leafed through one of the books. Gottcha. Someone had just written something like: Mr. Golub haven’t you ever had a nice, happy day even once in your life? And this was a expert-selected preview audience!

No, my imagined Williamsburgian would not have written that or even thought such a thing. I think he or she would think…War, death, anger. But where’s the irony?

Fortunately, there is not one ounce of irony in anything that Golub has ever painted, and this is one of the characteristics that makes him a great artist. He is our Goya, and if there isn’t much of a market for deeply felt, deeply articulated protest art, then we had better stop thinking about the market.

The level of passion in Golub’s work is high and, oddly enough, although there is no irony, there is certainly ambiguity. I would even risk saying that the level of ambiguity is existential. No amount of analysis or deconstruction will get rid of this level of fear and rage. He throws a monkey wrench into the art-historical machinery. He is not a Greenbergian formalist, but that kind of formalism is long gone and, at best, is a generator of intense looking at what is at hand; at worst, it’s a kind of art fascism. More to the point, Golub did not participate in the modernism/postmodernism false dichotomy; he had no tricks up his sleeve.

The Blue Tattoo (detail), 1998

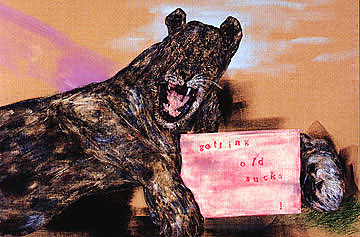

Getting Old Sucks

And now we come to the works of the last decade. Golub, in his seventies, hadn’t stopped. In fact, one might say he had come up with an entirely new body of work, on the surface more personal. The chapter in the catalogue that treats this work with great insight is aptly titled “Beware of Dog.” Dogs play a large part in Golub’s late vocabulary: snarling, vicious dogs. And then there are lions and skulls, and certain Greek myths are out in the open again.

Clearly, as Bird points out, Golub seems to have been influenced a bit by his wife Nancy Spero’s use of archaic imagery and words. There is even an acrobat figure that is a direct quote. Nevertheless, the vision is all his: Apocalypse Now. It is not just that death is on his mind. That would not be new. The snarling dogs and the tattoos exhibit anger, yes, but a rage that is more personal than political. But perhaps in previous works the political was always personal, and that was what caused the shock.

Bird quotes Theodor Adorno at the head of the “Beware of Dog” chapter. Adorno, a leading light of the Frankfurt School and, some think, an important player in Continental Philosophy, shall always in my book be remembered as the man who totally misunderstood jazz and trashed it with a vengeance, favoring twelve-tone music instead.

Here he is quoted from his essay on late Beethoven: “In the history of art late works are catastrophes.” Of course, when Adorno wrote this, Matisse had not yet arrived at his late, great style. But Adorno probably would not have even noticed.

I assume that Adorno was being ironic or rhetorical. At least I hope so, for it is generally conceded that Beethoven’s last works are some of his best.

Golub’s late paintings are magnificent and scary and, I firmly believe, will also eventually be seen as some of his best. The dogs are mad dogs. The death’s heads and the tattoos not only recall motorcycle regalia. but point to what lies beneath these cult insignias. The Sphinx has reappeared and is as always the embodiment of mystery, riddles and doom — but also of the interstitial. Prometheus is back, and there’s a roaring lion that holds a sign lettered with the words: “getting old sucks.”

In Strut, complete with a trio of buxom babes, one can make out “color and death” in Spanish but in larger, more visible red and white lettering is “ANNOUNCING the End of the World.” Who could ask for anything more?

Just remember that any theory of art, any critical methodology, any overview of contemporary art that doesn’t have room for Golub is not worth having.

(c)John Perreault 2001