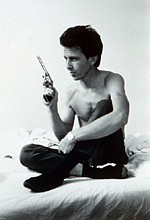

Larry Clark, “Untitled” (from Teenage Lust). Courtesy Luring Augustine Gallery.

What Photography Was

The battle for photography is pretty much over. If you can sell it as art, it’s art. Of course, bigger is better because bigger has got to be more expensive. On the upside categories are unstable — which infuriates the insecure. And since categories rule, who or what will be in charge when they are unreliable, vague or simply nonexistent?

We can, however, still squeeze a few puzzles out of photography in the form of questions never really answered (or questions answered with all the wrong responses). Walter Benjamin’s age of mechanical reproduction is over, and we are already in the age of digital production. But, whether painted, captured by light triggering chemical reactions or on/off codes, an image is an image, right? Yes and no. We still can’t escape the vehicle of presentation or the method of inscription. But those are for connoisseurs. It’s the image that gets in the way of the materiality. Paradoxically, it’s the image that’s the issue or, rather, how we interpret that image. Poetry has snuck in through the peephole.

Two current exhibitions allow me to get closer to what I mean: “Diane Arbus: Revelations,” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Fifth Ave. and 82nd St., to May 30) and “Larry Clark” at the International Center for Photograph (1122 Sixth Ave. at 43rd St., to May 5).

Diane Arbus: Young Man in Curlers at Home on West 20th Street, 1966.

The Arbus Argus

Freaks was a thing I photographed a lot. It was one of the first things I photographed and it had a terrific kind of excitement for me. I just used to adore them. I still do adore some of them. I don’t quite mean they’re my best friends but they made me feel a mixture of shame and awe. There’s a quality of legend about freaks. Like a person in a fairy tale who stops you and demands that you answer a riddle. Most people go through life dreading they’ll have a traumatic experience. Freaks were born with their trauma. They’ve already passed their test in life. They’re aristocrats.– Diane Arbus.

We can find all sorts of precedents for Arbus’ adventures in the abject. These, contrary to some superficial and dismissive readings of her images, do not include surrealism. Her bleak views of sideshow, sidewalk and backyard “freaks” do not contest reality; they expose it. Her friend, sculptor Nancy Grossman (quoted in Patricia Bosworth’s Arbus biography), indicates that Arbus was interested in “how a photograph can capture the soul of a person, which is why photography is so sinister and mysterious.” Souls? Arbus’s subjects are symbols. But symbols of what?

Symbols are not signs; they are polyvalent. Ungainly nudists, forlorn triplets, her “others” are us, are her. They are as real as Walker Evans’ Great Depression farmers. In other words, they are selected, posed, framed: caught. They are only as “real” as our response. Evans was hired to communicate poverty but, most agree, ended up communicating a kind of fake nobility. Arbus was not exactly sure what she wanted to communicate, but uncovered it as she went along: survival, danger, empathy, detachment.

The Arbus images are not as painful as they once seemed. We are used to transvestites and ugly couples in suburbia; we are accustomed to living rooms in Levittown and the Disneyland castle and to nearly empty movie theaters. Since her photos are all black-and-white and therefore in the past tense, we might easily see them in the light of when they were made. Would they have appeared in Vogue or Life Magazine? No way.

The only thing shocking about “Revelations” is when you see a photograph of someone you know. I did. It was of poet Gerard Malanga. So here’s the problem does the context make him a freak too? What if the dominatrix in another picture had been of my Aunt Alice who unknown to me had had a secret career?

Larry Clark, “Billy Mann, 1968.” From Tulsa.

A Needle in Your Eye

It was just kind of part of the scene because it was like organic and totally natural, and I wasn’t thinking about doing anything with the photographs or showing them or doing a book or anything, it just wasn’t in the consciousness until later. Then it became – well, I have all this stuff, it’s like visual anthropology, you know, it should all be put together – Larry Clark ( from an interview in Pataphysics Magazine)

I am not sure it is fair to say that Larry Clark is a direct descendent of Arbus, but it will do for a start. His work too is shockingly subjective at first look. The images are apparently still raw enough that the N.Y. Times covered the exhibition in the Metro Section, not the Arts and Leisure Section, offering a reporter’s piece about how the ICP was keeping a low profile in regard to the show and purposefully avoided government funding. The Metro Section does not go out in the national edition; just in case you didn’t know, the Times sells more copies to non-New Yorkers than to those of us who brave the poverty, drama and glamour of the Big Apple. Why this type of coverage, and not a review or feature? There’s a photo in the exhibition of a naked kid with a hard-on, aiming a gun at a bound girl. Also, in the images from Clark’s career-making, self-published book Tulsa (1971), there’s lots of shots of people shooting up speed.

Since teenage boy-flesh abounds in the photographs, is the fear of this art really a kind of homophobia? Looking at nakedness or evidence of arousal in public can be a problem. And although the artist is apparently not gay in the usual sense, his essay on Times Square boy hustlers (like his skateboarder pictures, like almost everything he has done) is heavy with male nostalgia, thinly disguised by social-issue, teen-problem concern.

In the so-called library rooms of the Arbus show you can read reproductions of pages from her notebooks, but not, as I recall, the last entry before her suicide, which according to Bosworth was simply: “The last supper.” In the 1972 Aperture/MoMA Arbus monograph, you can assay her more structured stabs at explanation, such as: “I never have taken a picture I’ve intended. They’re always better or worse.”

In the Clark show, the artist’s musings, including lists of drugs he has taken, are integral to the art. Like Weegee in his captions, Clark is a writer. There are, it’s true, free-association texts, but what could be a better haiku than this for a print of “Billy Mann, 1968” (from Tulsa): “death is more perfect than life. dead 1970.” Or the caption for images of a police informer being beaten: “every time I see you punk you’re gonna get the same.” Photography in books or in regulation-sized prints is closer to drawing and writing than it is to painting. The camera is a pen.

Like Arbus, Clark tells stories. Arbus crypto-narratives are single-image condensations of time. If she had lived, would she have tried her hand at movies? What kind of fables would they have been? Giants and transvestites? Nudists and wigs?

Rather than showing us iconic, stand-alone images, Clark presents image sequences. That he has become a filmmaker is an instructive natural development. Kids, 1995 (about Washington Square skateboarders and AIDS) and Bully, 1971 (based on a news story of youngsters who banded together to kill an enemy) are brilliant, upsetting films. In both, his camera eye lingers over teen flesh and teen drugs, but as in the photographs (I want to call them stills), these subjects are the bait. Before you know it you are asking yourself, why am I interested in this stuff? I don’t have teenage children, thank God. I don’t have a thing for boys, and any drugs I may have used in the deep, dark past had names and nicknames now unknown.

I personally find myself as fascinated by Clark’s work as I once was with Arbus’. Could I, an art critic, also suffer, as both photographers do, from scopophilia? Here I am using Freud’s definition: love of looking. Voyeurism is not a synonym, but a subset involving sexual gratification. The subject of voyeurism must not know, or at least must appear not to know, he or she is being watched. But most of the subjects of the photographs of Arbus and Clark know they are being looked at through the camera and will probably be looked at later by other people when the prints are exposed. To pose is to compose. Exhibitionism is the unacknowledged co-author of image culture.

Photography Is Not Reality

The mistake many make is to confuse photo images with reality. They are representations. They are constructed narratives; they are fictions. We, artists and viewers, if it is our bent, find the things that stand for or communicate what we want to express or, let’s face it, what our unconscious may need to tell us or others.

Personally I am extremely reluctant to photograph people, even people I know. But if I were telling a story through images I wouldn’t hesitate one minute to use friends or strangers as models. Is it so hard to believe that Arbus’s so-called freaks or Clark’s speed-freak teenagers are actors, or found images that stand-in for the photographer? Or that these freaks and speed-freaks are the subjects of voyeuristic fictions that allow unimpeded scopophilia? It is ultimately not what you are looking at that is important, but the looking itself.