Tibet Invades Chelsea’s Eastern Border

So far, the most significant art event this fall is the opening of the Rubin Museum of Art (150 W. 17th St.)in the huge building that once housed Barneys. Ages ago, Barneys featured boy’s and men’s clothes off-the-rack then went upscale and then uptown, leaving a vacant building behind on Seventh Avenue between 17th and 18th. Of course, MoMA is set to reopen this November in expanded quarters. And it will be great to see some of our favorite paintings and sculptures again in, we hope, a new and appropriate environment.

Unfortunately, some of us fear that the new $20 admission fee will be a barrier to the young, the poor, and the retired. For those who go often and can afford to become a member, the museum will still be a bargain. But that doesn’t seem quite fair, since MoMA benefits from its nontaxable, nonprofit status; the money the government does not get from MoMA has to come from somewhere. (Guess where: ultimately from me and you.) And yet…MoMA, like other museums, needs ever more income. My solution is that entrance fee should be based on income. The rich should pay more, not less. And students, the poor, and the retired, since they have little or no spare cash, should walk in free.

The Rubin Museum — devoted to the Hindu, Bon, and Buddhist art of the Himalayan region –is modest in size and in admission price (adults $7, seniors, students, neighbors and artists $5), but even MoMA will not have a staircase by Andree Putnam. And like the beautifully underplayed staircase held over from Barneys, everything about the Rubin Museum has been well-thought out and well-executed. Milton Glaser did the identity and the graphics. The educational components are perfect: just enough wall texts, skillfully written (which, as you know, is a rarity). And if you want, there’s free audio guides and alcoves with computer screens offering even more information. Given the complexity and the strangeness of the art, you could spend as much time at the Rubin as you would at MoMA, maybe even more.

Each of the six (!) floors — the Putnam staircase is at the core — allows a clear path or arc through the easily read thematic presentations. Helpful docents greet you, actually greet you, at each landing. Magnifying glasses are offered for viewing details of the complicated tankas or scroll paintings.

None of this is intimidating. It is, after all, not the entire Barneys that has been appropriated, but just enough to afford the right space for looking at some very esoteric art, requiring contemplation and perhaps more than a littlestudy.

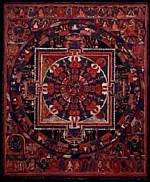

Mandala of Chakrasamvara, 1300-1399 (Himalayan Art Website)

There is a mass of unreliable testimony that Perrault did and could do all kinds of impossible things. It was supposed, for instance, that he practiced the art of self-levitation, of which so much appears in accounts of Buddhist mysticism…

— James Hilton, Lost Horizon

I count the Buddhist (and pre-Buddhist Bon) art of Tibet as one of the wonders of the world. I suppose, though, that since political borders have been fluid in that vast mountain region, one should more properly speak of the art of the Himalayas and immediate regions.

Like many, I will probably never visit Tibet. I make plans — which are more like guide-book fantasies — and something always comes up. I thought it best to go to Lhassa via Katmandu, where there are friends-of-friends and I might get a chance to acclimate before continuing on to the top of the world. Traveling by way of China seems a betrayal of one’s support of Tibetan independence. But now there seems to be a Maoist insurrection in the countryside of Nepal, making even Katmandu, the capital city, potentially dangerous.

Could I deal with the altitude? Last time in Aspen I got the bends, and that’s only 10,000 feet. Well, I suppose so, since I’ve read there are special oxygen pillows in the Chinese-run tourist hotel. But more important, how much is left of the real Tibet to see, or that one is allowed to see? Shouldn’t I see it before nothing Tibetan is left in Tibet?

I suspect, in any case, that the real Tibet is a Tibet of the mind (like the invisible kingdom of Shambala, north of Tibet) and I’ve already been there, lived there, left it behind.

How else can I explain my deep response to Tibetan art? I am in fact not even a Buddhist, although in my youth I briefly thought I was. I have nothing against compassion, but vegetarianism, which I assumed was required, made me ill (it appears I have carnivore Viking genes). Furthermore, hierarchies, no matter howbenign, are anathema to me, with the possible exception of heavenly hierarchies, if there are such. Rules supposedly for your own good are still rules. What else could my vivid dream of tunneling out of a Zen monastery have meant?

Nevertheless, Tibetan Buddhism is the unofficial art-world religion; look at the sponsor list of any Tibet House event. I myself was once on the board of the Jacques Marchais Museum of Tibetan Art on one of the densely populated peaks of Staten Island, Todt Hill — the highest point on the East Coast south of Maine. (“Todt” in Dutch, as in German, means death.)

There was no Jacques Marchais; that was the pseudonym of a New York dealer in Asian art who became so fascinated with Tibet that she built a reproduction of a Tibetan monk’s retreat facing the Verrazano Straights far below and then stocked it with tankas (paintings that can be rolled up) and small bronze sculptures. It turns out that, like myself, she had never been to Tibet, where there are the highest points or peaks in the world.

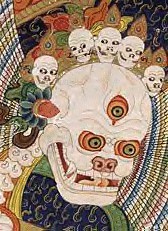

Just up the hill from Frank Lloyd Wright’s Usonian house (his only house in New York City), the Jacques Marchais has always tried for local outreach. Surely everyone on Todt Hill needs to know about Tibetan art. One docent — a kindly gardener-type who is a Miss Marple lookalike — told me of her first experience at an open house Saturday. A local stormed out of the picturesque stone building and out through the charming garden, dragging his kids. Having seen the many-armed statuettes inside, he was convinced that it was all “the devil’s work” and was going to report this devil-worship on Todt Hill to his parish priest. He simply did not understand that the fierce beings sometimes depicted in paintings and in metal statuettes are not devils, per se, but meant to protect you from devils, desires, and bad thoughts. Think gargoyles, not Black Sabbath.

You may not have done much reading in Tibetan Buddhism. You may not know who Milarepa is and that Naropa is more than poetry workshops in Boulder, Colorado. You may still get Red Hats, Yellow Hats, and Black Hats all mixed up, and not know a prayer wheel when you see one. Yet most likely you will get something out of Tibetan art. Contemporary art has already prepared you for it: your experience with repetition, flat fields of color or figuration, non-European composition (or anticomposition) will open the first of many doors.

You may not know about or believe in tertons or psychic lamas who can discover hidden treasures of esoteric teachings — sequestered in caves, inside trees or rocks, and unavailable until we are able to use them. But here’s a thought: perhaps the dispersal of Tibetan art and culture (on the face of it, yet another awful Diaspora) is like the terton-discovered texts of the past. We are ready to receive the teachings we now require.

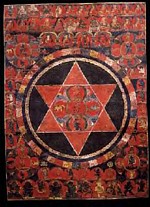

Mandala of Vajrayogin-Vajravarahi, Red, 1400-1499 (Himalayan Art Website)

It seems impossible…And yet I can’t help thinking of it — it’s astonishing — and extraordinary — and quite incredible — and yet not absolutely beyond my powers of believe.

What is, my son?

And Conway answered, shaken with an emotion, for which he knew no reason and which he did not seek to conceal: That you are still alive, Father Perrault.

— James Hilton, Lost Horizon

Of further assistance (I hope):

Yes, the iconography of the tanka scroll paintings is obscure to most of us. These images (think Greek icons) are meant to be mysterious, complicated, mind-stopping, but like their closest Western equivalent in the Eastern Orthodox Churches, they are meant to have a direct mystical effect; they are alive. They are wisdom vehicles, transcendence machines. Tibetan art is instrumental.

Even though many are single instances from broken sets? Certainly. Although you might think this is like trying to figure out the plot of the Stations of the Cross with only one station in front of you, each tanka has the same energy as the bigger picture. All cells from the same body have the same DNA, carry the same message.

Even those that are narratives of the lives of the Buddha(s) or saints? As in any art, how you tell the story is often more important than the plot. Besides, not all tankas are parts of narrative sets; sometimes the sets were collections of revered lamas, teachers, or saints. A Western equivalent might be separate paintings of each of the Apostles.

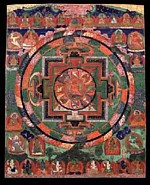

Oddly enough — or perhaps not so oddly if you respond most efficiently to abstract art — the mandalas may work best for you. You have read Kandinsky’s On the Spiritual in Art. You have read Jung, so even your brain is well-trained to expect something to happen when you look at a square within a circle within a square within a circle, etc. Suddenly you are “reading” pathways the way you might read the diagrammatic, alchemical mandalas of Europe. You are entering some beautiful palace, not unlike the palace in Second Temple Jewish mysticism.

Mandala of Yamari, Rahta, 1600 – 1600 (Himalayan Art Website)

At the inaugural exhibits at the Rubin Museum, each floor explores a particular theme. It is recommended that you start at the second floor and work your way up. Of course, being a well-known contrarian, I started at the top and worked my way down (as one should at the Guggenheim). Does this account for my backwards view of history? In this view, all artists decline as they get closer and closer to their beginnings. Amazingly, I still locate the golden age in the future.

Since the concise exhibitions here are laid out in the form of an ascent to higher realms, I would do the handout one better and start at the Theater Level, with Kenro Izu’s beautiful photographs: Sacred Passage to Himalaya, grounding oneself in photo-reality, as it were, before going on to Sacred History: Portraits and Stories on the second floor. The third floor offers Perfected Beings, Pure Realms. Demonic Divine on the fourth landing brings in a few borrowed Day of the Dead Mexican works to show other examples of scary art, but none are as “scary” as a Tibetan ritualistic bowl made out of a human skull or the gold-on-black tankas that will certainly ward off any art-world evil eye of envy or personal greed demon. More soothing are the Portraits of Transmission the next flight up. Finally, the sixth floor shows Methods of Transcendence, which includes a few spectacular mandalas.

Along with the link I have already provided above for the Rubin Museum, here are some additional ones for further illumination and information:

Tibet House at 22 W. 15th Street is now featuring the Repatriation Collection, a gift from the Rose Museum of Brandeis of what was formerly the Riverside Museum Collection of Tibetan Art.

The Jacques Marchais Museum of Tibetan Art has a website that features panoramas of the museum building and photos of a blessing ceremony by Tibetan monks, taking place on the museum terrace.

The Tibetan Buddhist Resource Center provides information online about persons and placesin Tibetan history, and more.

The Himalayan Art Website, sponsored by the Shelly and Donald Rubin Foundation, offers concise explanations 17,000 images of Tibetan art.