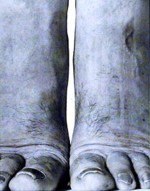

John Coplans: Self-Portrait (Feet, Frontal), 1984

The Body Politic

Oddly enough, one of the best essays written about Weegee, last week’s subject, is by John Coplans (1920 – 2003), this week’s subject. His essay, titled “Weegee the Famous,” is in Weegee’s New York (Schirmer/Mosel, 1982). He erred, I feel, on the side of attributing too much naiveté to that artist’s brutal vision. But this is how cults are born:

No other art form rivals photography’s capacity to be meaningless, to topple into a void. As a hedge against vacuity, ambitious photographers cloak themselves in a knowledge of art. But Weegee was an innocent, a primitive who described strong emotions and guilelessly jabbed at ours.

About as innocent as a second-story man caught on a fire-escape with the goods. About as primitive as Goya. About as guileless as Gypsy Rose Lee. About as innocent, primitive and guileless as Coplans himself.

Writer, curator, editor, artist — Coplans is my kind of guy. (I am a writer, curator, editor, artist myself. And poet. And sometimes actor: I played Vincent van Gogh on Dutch National Television. And artist’s model: Philip Pearlstein, Alice Neel, Sylvia Sleigh, Eleanor Anton, etc. The future belongs to the polymaths, but we never know how it will all shake down.)

Until the ’80s, Coplans whom most knew only as an editor, was also a curator and writer, but he had begun as an abstract painter. Now, after his death, I am sure he will be best remembered for his photography, and certainly not just as a founder of Artforum or one of its most daring editors (1971-74); nor because, when he was senior curator at the Pasadena Museum of Art, he gave Ellsworth Kelly, Robert Irwin, Roy Lichtenstein, Richard Serra, James Turrell and Andy Warhol their first museum exhibitions; nor for his Abrams tome on Ellsworth Kelly.

In Challenging Art: Artforum 1962-1974 (see my March 7 essay in the ARTOPIA Archive to your upper right), James Monte says that at the time of the founding of Artforum in San Francisco, Coplans was “a very good painter, hard-edge painter, much like Ellsworth Kelly with very simple shapes.”

Are those hard-edged, simple shapes echoed in his photographs? I haven’t seen the paintings, so I don’t know. I suspect there is a formal resemblance. Nevertheless, the subject matter, as in Mapplethorpe’s most notorious works, will all but erase the geometry, the studied push-and-pull, the classical design. Just as well; we have already seen enough of that.

But do we really want to see close-ups of an old man’s flabby, mole-flecked, wrinkled body, sometimes even with the penis and the testicles exposed or, as in a famous, earlier Vito Acconci Body Art piece, pressed and hidden between the thighs, making the old man that some of us shall become also an old woman?

I knew John Coplans hardly at all. I did not once write for Artforum when he was editor. But judging what I wrote in the Soho News, I was upset when he got fired.

My most vivid memory of Coplans, however, was well into his photography career. A filmmaker wanted a place to interview various people about the West Coast ceramics luminary Peter Voulkos, and Coplans generously donated his small loft in Soho. This was fine, but Coplans was there during the interviews, including mine, with more than enough booze in him to inspire his constant interference with the shoot. The old goat.

But his photographs! They make up for all his faults.

You can see the vertical triptychs that compose Serial Figures of 2002 at Andrea Rosen (525 W. 24th St., through June 26) and, if you can stand Madison Avenue and being jammed into those tiny elevators, earlier work going back to 1982 is at Per Skarstedt Fine Art (1018 Madison Ave., through June 26). The Skarstedt show is an essential catch-up.

If for some reason you wish to know more about Coplans’ life than Challenging Art provides, check out at the Smithsonian’s American Art Archives, where an interview by Paul Cummings takes us up to 1975. And although surprisingly uncorrected (names!), it gives a flavor of Coplans’ anti-Brit South African voice. I was particularly impressed that at the age of 40, he left swinging London and headed to America, without a job and hardly any money.

But to pick up where the American Art Archives lets off: after being fired from Artforum (read near the end of the AAA interview his theory or theories why), he moved on and founded Dialogue, the Midwestern art tabloid. Then in 1980, as a wall text at Andrea Rosen states, he gave himself what he called a “Watkins Scholarship.” He sold his collection of Carleton Watkins photographs, which enabled him to produce his own body of artwork. (He also collected the great potter George Ohr; examples are on display in the room that summarizes Coplans’ achievements.)

Totally plugged into the art world, surely Coplans knew the Body Art of Acconci, Robert Morris’ leatherman self-portrait, Mapplethorpe’s exhibitionist scandals, and Lynda Benglis’ famous dildo ad in Artforum. But more relevant to his work would be Hannah Wilke’s documentation of her mother’s wasting away in illness, and above all Alice Neel’s great nude self-portrait at the age of 80.

In a world of buff “beauty,” age and aging are taboo. No one likes to be reminded of mortality. Of course, Coplans turned his own old man’s body into landscape, and he himself, as is the case with much self-portraiture, hides behind his honesty. Starting at the Skardsted minisurvey — hands, feet, torso, etc. — and in the larger, six-foot-high late self-portraits at Andrea Rosen, there’s no doubt that Coplans framed and edited the image of his own body into dynamic fragments. The full body is never seen, although the late works come close.

Did Coplans produce photographs that relate to Body Art? Coplans’ relationship to Body Art is complex. In my view, Body Art was a kind of sculpture performance. Living sculpture would be the closest game. The body of the artist became the sculpture. It is a commonplace that all sculpture is a stand-in for the body (i.e., all sculptures are statues). This is reversed in Body Art: the artist’s body is the stand-in.

Some academics show their ignorance when they claim that Yves Klein’s use of live models to make paintings is a Body Art prototype. But seeing Duchamp’s cross-dressing RroseSelavy is perfectly justified in this regard. Rrose is Marcel. More contemporary examples would be Robert Rauschenberg (as a dancer), Carolee Schneemann (in almost everything), and Ana Mendieta when she used herself as a kind of temporary earthwork in the landscape.

Coplans, since he chose photography, produced Body Art only in the same sense that Cindy Sherman has in her self-portraits. Body Art and set-up photography merge. Photography was the way to communicate Body Art. Photography became the way to sell both identity and the body.

* * *

But I would also like to claim that the biggest influence on Coplans was not any of the artists I’ve mentioned, but Weegee. I will pull some sentences from his text on Weegee and you’ll see that the same words can apply to his own photographs.

Coplans, like Weegee,

belongs to a very American photographic vein, to tell it like it is. But the extremes to which he was willing to take this rhetoric make the viewer’s complicity in it apparent.

He, too, could be transformed into a fit subject for the kind of brazen exposure he visited on others.

In one sense his images were no less or more than ghoulish still-life to him.

His own tawdriness led him to where few other photographers were willing to go, and gives a terrible edge of remorseless tension to some of his images.

Finally, our awareness of Coplans’ excitement promotes these images of ostensibly banal horror to a level of artistic horror which is capable of moving us.