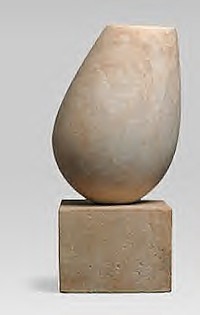

Brancusi: Torso of a Young Girl, 1922

Brandcusi

How much is enough? How much too little? By all accounts, Constantin Brancusi (1876-1957), soon to be repackaged as a protominimalist, did not produce much art compared to, let’s say, Picasso. Thirty-five Brancusi sculptures are now at the Guggenheim under the title “Constantin Brancusi: The Essence of Things” (1071 Fifth Ave. at 89th St., through Sept. 19).

On the grounds that an artist is the sum of everything that has been written about him or her and not just the latest blip on the curatorial screen, I turned to my library to reach into the not-so-distant past. Sydney Geist, in his 1975 Abrams book Brancusi: The Sculpture and Drawings, listed 215 works of sculpture, but admits that he “omits those objects made by the sculptor which the author does not think to be sculpture.” He counts the horrible academic sculptures of Brancusi’s youth; he also counts a few plaster models.

Years later, we are spared these at the Guggenheim, so that rather than the “essence of things” (whatever on earth that means), we are given the essence of Brancusi.

Weirdly enough, Geist included as sculpture the stools and tables of Table of Silence for the Tirgu Jui public park in Brancusi’s native Romania, but not the wonderful 1917 oak bench now in the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Did this mean in 1975 that seating could be sculpture if it was of stone and public, whereas private seating made of woodcould not? If sculptor Scott Burton had read Geist’s book, it would probably have driven him crazy. Burton’s art is proof that, regardless of context or material, furniture can also be sculpture.

Nevertheless, it is safe to say that Brancusi made only about 200 sculptures, give or take a few benches, and many of those sculptures were reworkings (not necessarily refinements) of but a half-dozen serious, serial themes: kissing lovers, sleeping heads, birds, fish, and “the endless column.” Picasso, as we know, produced thousands of artworks. I choose Picasso because Brancusi had as big an impact on sculpture as Picasso did on painting.

Perhaps comparing sculptors to painters is not fair. Sculpture used to take more time. To make matters more difficult for himself, Brancusi, that Romanian “peasant,” decided that the way Rodin did things (young Constantin had worked in the master’s studio) was all wrong. The standard way of making sculpture was to produce a model in clay and then hand it over to artisans who chipped it out of stone. Brancusi, according to Isamu Noguchi (who, in turn, had worked in Brancusi’s studio), disparagingly referred to clay as beefsteak. No, the best way to make sculpture was to do the carving yourself. Noguchi came back to that at the end, but only when everyone else, with the advent of minimalism in the ’60s, had moved ahead — or back — to the factory-made.

Few minimalists I know of would have touched the actual materials of their art. Well, I take it back; Robert Morris actually sawed the plywood for his early, severely geometric sculptures. When you are poor you do what you have to do, but the ideal sculpture tool became the telephone. Phone the factory with your instructions; have the sculptures shipped to your gallery or directly to some museum or other. Although I never, never would refer to clay as beefsteak (and rather enjoy hands-on making myself), I still think there is nothing wrong with telephone art — although once you know how Rodin made his sculptures, hands-off execution does seem rather 19th-century. I am fond of saying that you should be able to make a sculpture or a painting as fast as you can take a photograph.

There. Now you see how easy it is to write art criticism. I have established Brancusi’s importance, noted that some referred to him as a peasant, and linked this essay to my last two (on Noguchi) and my cycle of mini-essays on photography.

Let me flesh out some points:

The Progress of Sculpture

Once upon a time, the sculpture legacy seemed to go from Rodin to Brancusi to Noguchi. As I have already indicated, Brancusi worked in Rodin’s studio; Noguchi worked in Brancusi’s. Since these connections were brief indeed, making much of them is equivalent to saying that I am the heir to Duchamp because I once saw him get out of a taxi on 12th Street. Or that I am Clement Greenberg’s son because I once served on an art jury with him and was party to hiding his bottle of scotch.

But the meaning is more important than the truth. Figurative apprenticeships notwithstanding, what we are getting is a grand march to abstraction. The new view, whether Noguchi is included or not (probably not), is that Brancusi leads to Donald Judd. After all, Brancusi did once say about his art that, “The observer knows what is there at a glance.” The Guggenheim itself — though we thought it had pretty much lost its position as an arbiter of taste and art history — points to this direction by way of “Mondrian to Ryman: The Abstract Impulse” on the upper ramps, supposedly there to give some context to the Brancusi offering.

Making minimalism, rather than Jules Olitski’s Color Field painting, the end point of modernism allows us several advantages, not the least of which is that we might not need postmodernism … or pluralism.

First of all, almost everyone but Clement Greenberg could see minimalism as an extension of modern art in its march-to-total-abstraction mode. Yet Greenberg thought Barnett Newman and Ad Reinhardt were bad enough and had gone too far already. His disciple Michael Fried thought minimalism wasn’t art, but theater.

Secondly, neatness counts. In fact, neatness counts so much that many would be willing to sacrifice Pop, Photo-Realism, and Judy Chicago — and probably even Feminist Art and Body Art, never mind conceptualism, if art could have a coherent history again, a story worth telling.

Finally, from an institutional point of view, as long as minimalism was excluded from modernism, there was a need for postmodernism and pluralism too. Could it be that no one noticed that collectors had long since stopped listening to Clem, that no one noticed he had passed on to bully heaven or bully hell?

Presentation

But before we get to the hard part, I should say that the current Brancusi survey is a nearly perfect introduction to the evolution of abstract art (if you still need such) as well as the perfect installation of an exhibition in the difficult Guggenheim space. No matter how spectacular the atriumlike rotunda, we are still stuck with Frank Lloyd Wright’s perverse notion of how to display art: in little, tilted-floor alcoves. Here, the Brancusi sculptures are allowed to stand up to the alcoves. Less really is more. There are never more than two or three to an alcove and, frankly, they need that kind of space. You have to walk around them!

And you can. Since he apparently had no use for other people’s art, Mr. Wright is probably rolling in his grave. For once, the sculpture outclasses the building.

If you take the half-circle elevator to the fourth level and walk down, you’ll get a succinct survey of Brancusi’s journey from The Kiss to the great bird sculptures. He does indeed get more and more abstract (but never, never totally so), and the pedestals grow in importance.

Surely, after the 1989 Burton-organized MoMA exhibition of Brancusi’s pedestals (“Artist’s Choice: Burton on Brancusi”), we cannot look at them in the same way. They too are sculpture. Beginning midway down the ramp, imagine the sculptures on other pedestals, standard or fanciful, and you will immediately understand that the pedestals had became integral. Late in life, Brancusi labored on them more and more, and at the risk of seeing every one of his artworks as a column of sorts, it is illuminating to see the pedestals as not separate from the carving or bronze at the top. His sculpture became a higher form of stacking.

As someone who once got an A+ for some very mediocre drawings simply because he had the good sense to present them nicely matted, I know how much presentation determines the way we see art. Brancusi understood this before anyone else; well, nearly before everyone else, for we should not forget that his pal and, later, American sales representative Duchamp demonstrated that mounting a bicycle wheel on a stool turned it into art. Whether influenced by Duchamp or not, Brancusi obviously wanted to control how his carvings were displayed by insisting that the pedestals were also the work. This is equivalent to a painter insisting that the frame is part of the art.

What people do with your art once they buy it is a constant problem. If your art is a small sculpture, it will end up on a bookshelf or coffee table. If it’s a small painting, it will end up in the hall or in some decorator arrangement with a number of other small paintings and drawings, prints, photographs. Help!

Make it big. Make it too big. Only then will it stand up to the clutter.

The Master Plan

Since it was Mr. Wright’s idea to show art on a spiral ramp, one can deduce that he of all people was linear to a fault. He believed in a master narrative. That all art history obviously led up to Frank Lloyd Wright should go without saying, right?

The Guggenheim ramp therefore is the perfect vehicle for the notion of progress, from figuration to semiabstraction and on to total abstraction. Remember that the Guggenheim was originally The Guggenheim Museum of Non-Objective Art.

Yet Brancusi never stepped off the cliff. All of his sculptures, even the succinct series of heads that culminates with Sculpture for the Blind, are still grounded in representation. But he was getting there, which is one reason he was always considered so important to the working out of the master narrative of modernism.

Now he is embraced as a predecessor of minimalism, which, with the evidence before us, at first glance seems odd indeed. Minimalism is never whimsical, as some of Brancusi’s lesser efforts are (here see the revolting King of Kings or elsewhere, his Penguins ). Also, everywhere we see evidence of Brancusi’s hand, even in the shiny, shiny bronzes. All were finished by hand because he knew no machine could get the perfection he required. Minimalism, however, is about the artist’s choices, not the artist’s touch.

Pluralism and Pop Art, emerging in the ’60s, destroyed the modernist narrative, which, as any such master narratives tend to do, had became prescriptive rather than descriptive. Oh, how we loved that master narrative!

Although Brancusi sculptures are wonderful indeed, some part of the unexpected emotion they now engender has to do with their place in a narrative now lost. Although stories can be used towards wicked ends, we still need them as temporary maps. Now that postmodernism is over, perhaps better storiesmay be told, such as …

Brancusi and Sex: The Untold Tale?

Brancusi can fit in a new history of art that concentrates on gender and sex. Although the gross Princess X of 1915, supposedly a portrait of a young woman, is breathtakingly phallic, the elegant Torso of a Young Man (in all its versions) paradoxically has no visible maleness. Has the divine, alchemical hermaphrodite made its way into Brancusi’s self-proclaimed art of essences? Or was Brancusi, who never married and lived alone, trying to tell us something about his own bent?

I love using artist quotes and quips, particularly when they have been cited over and over and become true — true insofar as they determine how the artist is seen or, rather, heard. They are often like Zen koans or the sayings of a Taoist sage. What did Jackson Pollock really mean when he said, “I am nature”? What did Brancusi mean when he said, “Nude men in sculpture are not as beautiful as toads”?

A quote has to be quotable, as it were. I am certain that the quote people will pull out of this very essay will be: you should be able to make a sculpture or a painting as fast as you can take a photograph.

Brancusi thought he was competing with Michelangelo and the monumental tradition of sculpture, not with Rodin, and certainly not with photography. This is why he said, “Michelangelo is too strong. His moi overshadows everything.” How useful is that moi! One could also say that Picasso’s or Gertrude Stein’s or Martha Graham’s moi overshadows everything. And today? Alas, there seems not to be any contemporary artist, writer, or dancer who has a moi big enough to overshadow anything taller than a thousand dollar bill.

On the other hand, it may have been the idealized masculine body that overwhelmed gentle Brancusi, best friend of Modigliani and Erik Satie. “Who would imagine having a Michelangelo in his bedroom,” quipped Brancusi, “having to get undressed in front of it?”

Or: The Court Case That Invented Brandcusi and Saved Abstract Art

Brancusi can also fit into a new history of art told in terms of art law. Abstraction is now such an important part of art that we may forget there was a certain struggle involved. Brancusi became Brandcusi because, through no fault of his own, he profited from that struggle.

As recounted by David Lewis (Brancusi, 1957, Alec Tiranti, London), in 1926 a shipment of Brancusi sculptures was held up by U.S. Customs, which regarded them not as “works of art, which may enter free of duty, but as manufactured implements, and stamped them ‘block matter, subject to tax,’ the tax being 40%.” Edward Steichen had to pay $240 tax onthe $600 Bird in Space. Brancusi contested, and the rest is history. Or used to be history.

“Would you recognize it as a bird if you saw it in a forest,’ asked Justice Byron S. Waite, “and take a shot at it?”

“Could not any good mechanic,” demanded First Assistant Attorney-General Marcus Higginbotham, “do just as well with a brass pipe?”

“Surely if he could, testified Jacob Epstein,” who appeared for Brancusi, “as soon as he does, he becomes an artist.” But the best is yet to come. Brancusi won, and for a number of years nonrepresentational sculpture was allowed to enter the U.S. without import duty, providing the works had “representational titles.”

Conclusion: The Secret of Brancusi’s Success

Committed bachelor Brancusi was a great cook. He may have called clay “beefsteak,” but he had a way with meat:

The man, now well over 70, living alone, as he has always lived, in his studio has now become famous for his broiled steaks cooked by himself at his own fire which he himself serves as though he were a shepherd at night on one of his native hillsides under the stars. A white collie named Poliare used to be his constant companion, reinforcing the impression of a shepherd which, with his shaggy head of hair, broad shoulders and habitual reserve, he seemed to his friends to be.

— poet William Carlos Williams, quoted by David Lewis.

* * *

Was Brancusi a peasant, a primitive like his pal Henri Rousseau? Did he really walk from Romania to Paris on bare and bloody feet? I know this: modern art would not be the same without him. Some of his work may now look cloyingly sentimental, but what to this day can match The Birth of the World/ Sculpture for the Blind or his Bird in Space?

I despise his talk of essences. And thanks to sculptor Athena Spear’s Brancusi’s Birds, found in my library, we now know that his commitment to the truth-to-materials doctrine of doctrinaire modernism was more in word than deed:

Brancusi never exploited the elasticity and structural strength of bronze. Another example of his untruthfulness to the nature of the material is his disregard for the very limited elasticity of marble in the case of the Bird in Space; as a result, half of his marble birds are broken at the waist in spite of the metal rod inserted in them.

Here, we really have to ask, what does truth-to-materials actually mean? Would we be more correct if we thought of modernism as a useful myth, offering guidelines rather than chains? Did postmodernism really set us free? And now that it’s over, what new burden can we assume? Is taste the enemy?

Brancusi began as a legend, and he ended as one. According to David Lewis, he “requested to be buried naked, directly in the earth but the French officials would not allow this, considering his request to be in bad taste.”