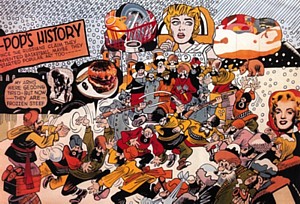

Erro, Pop’s History, 1967

Too Political To Be Pop?

This is the year of the second Icelandic invasion; the first happened before Columbus. Adventurous Icelandics settled briefly in what they called Vineland. You can even read about it in one of the Icelandic sagas. Now its art that’s coming over. First, Dieter Roth at MoMA and P.S. 1; now Erró at the Grey Art Gallery of New York University (100 Washington Square East, to July 17) and Goethe-Institut (1014 Fifth Avenue, to July 16).

Erró is commonly thought to be one of the European Pop artists. Iceland is part of Europe, although far from Norway and Denmark, the countries that in succession held it as a colony. Then too, Erró has lived for an awfully long time in Paris. The question isn’t Euro or not, it’s how Pop is his Pop?

Like Roth, Erró had a name problem. Roth, who favored lower-case letters, became rot, then roth, although now we use Roth. Perhaps it is an Icelandic thing. But unlike Roth, who adopted Iceland, Erró was born there, as Gudmundur Gudmunsson, in 1932. Icelandics, like Australians, have a tendency to wander over the earth: You never know when one is going to pop up. It’s their sense of isolation and, on the part of the Icelandics, their Viking blood.

Ensconced in the Spanish village of Castell del Ferro in 1953, liking it very much, our Gudmunsson changed his name to Ferro. In 1967, when he was living and working in Paris, the artist Gabriel Ferraud (in French, sounds like Ferro) sued him over his appropriated name. So Ferro dropped the F. One gathers he did not have a lot of monogrammed handkerchiefs or luggage and that he had the time to white-out the offensive F on his calling card and stationery.

But I am not writing about Erró because of his name or because I like Iceland.

(I am enamored of the light and the air.) I am writing about Erró, my fondness for Iceland aside, because he deserves some attention. Twice now I have seen impressive selections of his large paintings at the Reykjavik Art Museum – Harbour House. In 1989, Erró donated over 3000 works to this, the major modern museum of his homeland.

Although his work is pictured in most books about Pop Art, he has not had the exposure in the U.S. that he has had in Europe or, of course, in Iceland, where he is a celebrity.

Erró participated in the European version of Happenings and, it appears, was always involved in political protest. His paintings reflect that. He’s even made films. His 1963 Concerto Mechanique, or the Madwoman’s Mechanical Metamorphosis (in collaboration with Eric Duviver; commissioned by Sandoz, the European drug company) can be seen at Goethe-Institut and at the Grey, where it is accompanied by some startling Dadaistic props. Grimaces (1962-67) has 100 artists grimacing. A poster provides identifications: Claes Oldenburg, Jim Rosenquist, Man Ray, Andy Warhol and many others. In the film, the faces pass by, disguised by time as well as face-pulling. Is that artist and critic Lil Picard? Yes.

But it is as a Pop painter, rather than a filmmaker, that Erró is most celebrated. He admits it was his encounter with Pop Art in New York in 1963 that set him on that course. He saw the now-famous New Realists show at the Sydney Janis Gallery. Very trans-Atlantic, it even included Erró’s Swedish friend Oyvind Fahlstrom. Fahlstrom’s comic strip-inspired “variables” still stick in my mind.

What makes Erró Pop so different from American Pop — and even gives it some distinction amongst the Euro Pop crowd — is its overt politics.

Erró Pop, like Fahlstrom Pop, has distinctly political subject matter: the Cold War, Algeria, Vietnam are all grist for the mill. At this very moment, Erró is probably working on Iraq.

Both Erró Pop and Euro Pop are quite different from Pop Art proper — which can only be American. Pop Art is inordinately cool, like television. Of course, the more we know the works of Rauschenberg, Rosenquist, and Warhol, the more socially minded are the artists and socially engaged the art. But it never hits you in the face like Erró Pop. Is that what is so refreshing about Erró’s painted, comic-book collage? Erró Pop is linguistic rather than nostalgic, orgiastic rather than formal. He uses comic-book imagery as words and sentences, but not as signs of signs. He is more like Peter Saul than Roy Lichtenstein. Chaos abounds, along with lots of lusty good cheer.

Erro, Tiger Woman, NB (Femme Fatales), 1987-95

So here we have two very different exhibitions of Erró’s work: ‘Worldscapes” at the Grey and “Femmes Fatales” at Goethe-Institut. (A third, “Mao’s Last Visit to Venice,” is a recent suite of prints “reprising” an earlier Chinese Paintings series, but since they are shown in a lecture hall they are not seen at their best.)

“Worldscapes” is a scholarly exploration of Erró’s development from early, Dada-like collages, through his “Pope,” “Astronaut,” “Socialist Realist” parodies, to the “Scapes,” of which there are only two full-blown examples: Pop’s History (1967) in which cartoon Russians are shown with Warhol, Lichtenstein and Wesselmann images; and the black-and-white Simon Clay Wilson-scape (1989), an homage to a co-worker of R. Crumb at Zap Comics. As the catalog admits: “Given the compact size of the Grey Art Gallery, his recent paintings in “Worldscapes” are represented by preparatory collages. …”

This is fine for me. I’ve already seen a lot of the big paintings, so it is a pleasure to get a closer peek at Erró’s work process. First he makes an elaborate collage out of images from comic books and other sources, and then he paints the results from a projected image. We saw at the Rosenquist retrospective some of that artist’s preparatory collages. Erró’s collages are less cubist; the teeming images, as in his best paintings, transcend both composition and taste.

The catalog, through the judicious use of details of paintings, fills in some of the gaps. But short of flying to Iceland, I recommend that after the Grey Gallery, you see “Femme Fatale” uptown for a more direct appreciation of Erró’s energy. Not hampered by the lighting requirements of works on paper, in a chic, light-drenched second-floor room opposite the Metropolitan Museum of Art (the paintings should be in the Metropolitan), the ten panels from Erró’s Femme Fatale Series (1987-1995) “pop.” In a vertical format, the images are less diffuse than the horizontal “Scapes,” but just as crisp and outrageous.

We are on the edge of narrative. In Space Suit, Wonder Woman emerges from a metallic garment; a buxom Joan of Arc makes two appearances in two separate paintings. In Big Bride — here comes Kill Bill’s Uma Thurman! – the bride wears blue, and side panels seem to show the same figure weeping, then drowning. There’s also Double Wedding, in which villains are taking vows, and Sisters, one a nun and the other with a gun. There are words, here and there, when appropriate (or inappropriate). Day by Day Girl has the following dialogue between an orange-faced woman and another in a red helmet: “Oh, Celia …how on earth will we be able to GO ON with this hanging over us?”…”Day by day, Girl.”…”We haveta learn ta live DAY by DAY.”…”And our glorious mission? What becomes of that?”

What is the this hanging over them? What is the glorious mission? We’ll never know. What we do find out is that Erró obviously likes superwomen. Wearing bras of steel, these are some pretty tough babes. It is not so much a question of where he finds these images (I spotted Tank Girl and Bat Girl), but how and why he puts them together. They have none of the decorousness of Lichtenstein, the reverie of Rosenquist, the dankness of Warhol. They are pure Erró Pop.