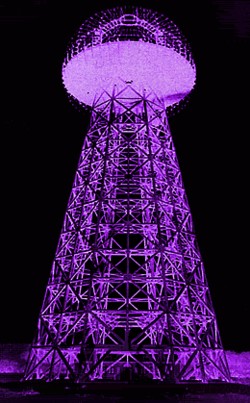

Nikola Tesla’sPowerTransmission Tower

The Future of Opera

In another life as an arts administrator — once my “day job,” as theater people say — whenever myassistant felt she might have exceeded her brief, she’d preface her confession with the phrase “just so you know.” For example: “Just so you know, I have paid Consolidated Edison rather than Verizon.” To this day she does not know that I came to dread the phrase. But sometimes it comes in handy. So…

Just so you know, I have written about music in an art context before and maintain that it is not always as separate from the visual arts as the tradition-bound may maintain, Gotthold Lessing and his lesser followers be hanged. Each art does not have to be true to itself.

The first piece I ever wrote for the Village Voice as an art critic in the ’60s was about Meredith Monk, the now-famous choreographer, dancer, composer, vocalist and mixed-media artist. Later I wrote about La Monte Young — post-Cage pioneer minimalist composer. Most people have not yet caught up with him because he refuses to release the tapes of his influential, droning and eardrum-bursting Theater of Eternal Music, created and performed with Marian Zazeela (who also provided projected mandala visuals), pre-Velvet Underground John Cale, Tony Conrad, and Jon Gibson, whom we will come to later. The sound of the endless and still-unfinished piece called The Tortoise, His Dreams and Journeys (1964- ) was so loud that entering the small auditorium where it had already begun behind closed doors was like walking into a hot swimming pool. (I was first exposed to Young’s music in San Francisco in 1961 at avant-gardist Ann Halprin’s dance deck; we young poets, Joe Ceravalo and myself, had met him through poet Diane Wakoski. He was more or less the composer in residence: burn a violin, set some butterflies loose in a concert hall, etc. But he also played a mean sax.)

A bit later I myself performed in a music piece by poet Jackson MacLow in Yoko Ono’s pre-Beatles loft. As a performance artist, I “choreographed” a solo to music from Swan Lake and constructed the music for my projected theater piece called Lower Forces, in which the audience read the script from the screen rather than seeing anything actually performed.

As any student of art must now know, painting and sculpture have not always been practiced in isolation. We can point to the Futurist andDada artists and poets for interdisciplinary cross-fertilization and for examples of — perish the thought — theater and, even more shocking, music. John Cage, our hero, clinched the deal and in the process inspired Happenings, Fluxus Events, Performance art and other forms of mixed-media theater, some of which might as well be called “operas.”

Although most significance shifts in form are collective, at this point it looks as if we can give some credit to La Monte Young for minimalism in music, at its most extreme. Philip Glass, whom I first heard performing in an art gallery under the enthusiastic patronage of minimal artist Sol LeWitt, and even Steve Reich — both of whom we like — seem crowd-pleasing in comparison. (More recently, we like Phil Kline’s Silent Night, his famous boombox piece, heard Christmastime in Philadelphia again and at other sites around the nation, and certainly his Zippo Songs, with texts derived from messages scratched on cigarette lighters in Vietnam.)

This brings us to Jon Gibson, whose work as a composer is within the minimalist style. He’s now composed a one-act opera with a libretto by Miriam Seidel who, like myself, is a bit of a polymath. She is a writer, dance critic, sometime art critic, and has and plays a theremin. You know what a theremin is. Think Bernard Hermann’s great music for The Day the Earth Stood Still. You wave your arms in the air and a single line of music slides and trembles in eerie ways. Or happy ways, if you think of “Good Vibrations” by the Beach Boys.

But Seidel’s brand-new opera, called Violet Fire, does not have a theremin in sight. Although Leon Theremin’s life might also make a good opera (after his success with his musical instrument in the U.S. he was kidnapped by the K.B.G. and brought back to the U.S.S.R.), Violet Fire is instead all about the scientific genius Nikola Tesla. I saw it recently in Philadelphia, where it was performed for two evenings at Temple University. Billed as a multimedia opera, it is very visual indeed, and as a minimalist music fan and a Tesla fan, I have no choice. I just have to write about it.

I am interested in opera. I backed into this most collaborative and interdisciplinary form because of my love of Baroque and contemporary music. One of the peak experiences of my adolescence was suddenly being able to hear simultaneously the various voices in a Bach Brandenburg Concerto and then learning one could do that too with Bop. So, to make a long story short, after hearing Philip Glass operas — and learning that jazz and Baroque music are not only both polyphonic but also employ improvisation — we expanded by listening to Monteverdi, Lully and Rameau, and then Handel and, yes, Vivaldi and ever forward in time.

John Cage once said that all you had to do to make something interesting was to have at least five things going on at once. So, surprise, what traditional art form has five things or more going for it all at once? Words + sound + people singing + people moving around + painted stage sets = opera. Opera, impure, glorious opera, Walt Whitman’s favorite form ofentertainment.

* * *

Three days after seeing the American premiere of Heinrich Sutermeister’s marvelously complex The Black Widow (1935) at the Harry de Jur Playhouse in Manhattan’s Lower East Side, I made my way to Philadelphia to see the first public performance of Violet Fire, another one-act opera. There is something fetching about one-act chamber operas: the spell is not broken by a trek to the lobby and all the fuss that entails.

But I wonder if multimedia opera is the wave of the future. I did not see Steve Reich’s The Cave, but have heard it without the multimedia accoutrements it requires. I have looked at and enjoyed his Three Tales, now in a DVD and CD package, the former with visuals and better sound. The Black Widow, performed by the Gotham Chamber Opera, skillfully used film and image projections. Violet Fire has multiple projections too. How else can you sing the story of Tesla?

Nikola Tesla was the man from Croatia who invented alternating current, tamed Niagara Falls, invented the power grid, was cheated by both Westinghouse and Edison, had a plan for a Star Wars defense system and a death ray that would ensure world peace, seemed to have contact with extraterrestrials (or according to some was an extraterrestrial himself) and, best of all, was convinced he could provide and wirelessly transmit electricity free to all. Newspaper headlines, period photos, computer-generated images of his power tower collapsing, pigeons whirling, dynamos and diagrams and two very real Tesla coils all needed to be seen. Or as this opera proves and as Tesla sings: “Perhaps I was a little / Premature, perhaps / Too far ahead of time.” The surprise for me is not that Seidel’s libretto bounces around in time — adding to the Tesla man-outside-of-time theme — but that it is poetry.

Gibson’s lovely, efficient, and sometimes even beguilingly astringent music was played onstage by Philadelphia’s Relâche Ensemble. I haven’t heard much of Gibson’s music before, aside from a few things on WNYC radio’s New Music venue. He’s is one of the founding members of the Philip Glass Ensemble, so minimalism could have been predicted. There’s just enough minimalist churning to suggest electric dynamos, but no predictable Phil Glass crescendos. The vocal writing is surprisingly beautiful. I was thrilled.

But on with the plot: Tesla, although routinely hounded by the press for predictions of things-to-come, was deadly poor at the end. He lived alone in a hotel room, his only joy the daily feeding of pigeons in the park. A white pigeon was one of his favorites and, of course, functions as the symbol of the mystical, blinding light he seems to have experienced. Here I would have preferred a literal blinding light rather than the Isadora Duncanesque dancing that just seemed to get in the way of both the high tension, as it were, and the restrained, allegorical, multimedia pageantry. Violet Fire, like Glass operas and the preludes to French Baroque operas, is a moral pageant: virtue arguing with beauty, truth with form. But in this case the argument is between science-as-poetry against commerce and doom.

I wouldn’t have had a real problem with the union of Tesla and the symbolic white dove/dancer at the end, walking off like bride and groom, if the staging, the acting or direction had not made it seem that the dancer in the ivory tunic was Tesla’s ideal woman. From reading several Tesla biographies, it really doesn’t seem he had any ideal woman in mind. Or man, for that matter. He really was a stranger in a strange land — or, asthe following made-up conversation attests, a kind of saint.

“But don’t you see? The White Dove is the Shekhina, the feminine aspect of God that accompanied Israel in exile,” a friend explained, outside in the lobby.

“Tesla wasn’t Jewish,” another friend interrupted.

“The author is and I am,” replied my friend. “In any case, you don’t have to be literally Jewish to be one of God’s chosen people.”

“Maybe he just mystically unified his masculine and feminine aspects,” volunteered someone standing nearby.

This is another way of saying that the best thing about Seidel’s libretto is that Tesla, one of the world’s greatest loners, is left as he was: a mystery to all.

Other things I learned:

Like all the operas I really enjoy, Violet Fire has a lot of subtext. Fortunately, words supported by engaging music give you time to think about what’s going on in a way that most theater and all but the slowest of films do not. Any story is only as good as its subtext. The subtext is unspoken; the subtext is the real meaning of the text or the action and is usually more complex that discursive language will allow. Actors will know what I mean.

Vis-a-vis acting, the great thing about opera — when divas are kept under control — is that the music replaces most of the arm-waving and face-pulling usually required by nonmusical drama.

And what next? The multimedia effects essential to Violet Fire mean it can be presented in many different kinds of venues. Expanding these effects would make Brooklyn’s BAM a natural. But if not BAM, then why not the charming and fully restored turn-of-the century Harry de Jur Playhouse at the Henry Street Settlement in New York? And why not a nicely produced DVD?

Old City Gallery Hop

Old City in Philadelphia, down by the Delaware waterfront and around the Benjamin Franklin Bridge, offers a significant, small-city cluster of galleries. Here are a few of the “bests” resulting from my walk:

David Goerk at Larry Becker (43 N. 2nd St., to March 30) shows small paintings cum wall sculptures, in which various geometrical forms — and some irregular circles — jut off the wall and are faced with encaustic. Some of my favorites were the all-white Double White (a six-section grid), White Yellow White (three rectangles in a vertical, the yellow one at the center), and 6 x 4 (a red geometric with a slanted upper edge). All the works have a frontal, but very cool, painterly interest, and sidewise a sculptural gesture in layers of wood and gesso. Although none was larger than the largest at 11 inches high, I had the feeling that they could hold even much larger walls than the ones here.

Temple Gallery, a project of Tyler School of Art/ Temple University, has “analog click click” (at 45 N. 2nd St., to March 6), a group show on the theme of digital technology in art. We have seen Carl Fudge’s semipattern paintings in N.Y. before, and Lia Cook’s computer-based, realist weavings are known too. New to me and promising is a wall piece (Blotch) by Cindy Poorbaugh and the ceramic sculpture and digital drawings by Mark Lueder. Lueder works out his forms on the computer and then constructs them of clay. The ceramic piece by itself is credible enough, but in conjunction with the computer printout it zings.

Speaking of ceramics, at The Clay Studio (139 N. 2nd St., closed Feb. 15) Denise Pelletier’s hanging installation called Mute was hardly mute. A suspended grid with a concave indentation, it was made up of hundreds of black, hand-made, invalid feeders (“sick cups”) fashioned out of sanitary porcelain when the artist was in residency at the Kohler Company in Sheboygan.

Very beautiful and slightly strange too — strange is good –are Keiko Miyamori’s tree rubbings at the Community Gallery, Nexus Foundation (137 N. 2nd St., to Feb. 28). Each framed rubbing is titled after the Philadelphia location of the tree involved. Beneath each, for this incarnation, is a little shelf with a harmonica covered with a similar rubbing. Two keyboards on opposite sides of the room and a prism at the center complete the installation, but it is the rubbings that are most winning and could indeed stand very poetically on their own.

Finally, I also liked Laurie Reid’s water-altered white paper “drawings” (?) at Gallery Joe (302 Arch St., to March 13). Barely marked or inflected, they are subtle reliefs, as much as drawings or works on paper. They are the paper.

Note: Yours truly, the polymath and founder of Artopia, will be showing “Seascapes & Mended Stones” at 473 Broadway Gallery in N.Y. from March 2 to 13. Reception: Thursday, March 4, 6-8 p.m. Briefly, these are petroleum-impregnated beach sand on found paintings and painted plywood, along with a floor-piece made of broken and glued-back-together beach stones. Intrigued? Check out my website underPerreault’s art.