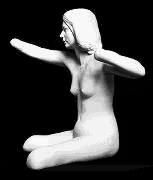

Marc Quinn, Helen Smith, 2000

When you first walk into the gallery, you will probably be attracted to the smooth, white marble and the semblance of sensuous flesh. How hard, white stone became associated with the softness of the body has to do with illusionism and cultural conditioning. That polished marble still signals art with a capital A is further evidence — evidence you can feel — that the mind as well as the eye plays tricks on the heart. That Greek statues were originally painted is neither here nor there. Facts are not important; convention is what counts.

Marble short-circuits modesty. We are allowed to look at what purports to be the naked body. Of course, through the very nature of the material and the carving and polishing, hair and pimples have gone away, raising high expectations for real-life nudes, never as comely, mathematically curvaceous or muscular as those stone gods and goddesses or elder statesmen.

But wait a minute. The missing limbs you first thought were just the results of ancient wear and tear are the missing limbs of the subjects. The rounded, truncated parts tell us that. Because we connect in a prelogical way with depictions of the human form, we ourselves suddenly feel physically challenged. Empathy and voyeurism are confused.

Yes, Marc Quinn’s statues are shocking. Perhaps this is why no commentary I have yet seen about Quinn’s depictions has grappled with their status as sculpture. Although the current exhibition at Mary Boone (54 W. 24 St., to Feb. 26) is the first U.S. showing, works from the Quinn’s controversial series were first displayed in Europe as long as five years ago.

Minimalism in sculpture — exemplified by Sol LeWitt’s three-dimensional work, Donald Judd’s boxes, and prime Robert Morris geometries — can be seen as an effort to thwart empathetic projections of body image upon inert matter in order to make truly abstract sculpture or “specific objects.” In this way the normal operative of three-dimensional art was destroyed or, at the very least, illuminated. It might be informative to see Quinn’s statues as a related ploy.

On the other hand, in Quinn’s case the sculptural or antisculptural is not the point; the content is. Or I could say it is the disruption between the artist’s stated intentions and the feelings, aesthetic and otherwise, these difficult works may cause. Quinn has indicated he wants to honor people with corporal disabilities by casting them in the heroic mold of the tradition of the idealized human form, as expressed through marble. Each statue comes with the full name of the model.

“It’s more about looking at something, and what you bring to it from your knowledge of the context of art. And so, what is acceptable and aesthetic in art is very shocking and different in real life,” said the artist in an April 2000 Sculpture Magazine interview. “I was in the British Museum, and I thought, ‘If you took these [marble sculptures, many of them missing limbs] literally, what would the modern versions look like?’ But the sculptures are also celebrations of the sitters — they are heroic sculptures of these disabled athletes.”

From this assertion we learn something not evident in the exhibition itself. The models are athletes. We can assume they are used to being looked at in real life, and we may not feel so squeamish about our gaze. In real life we are not supposed to stare at unusual people.

Is there any expressiveness or emotion offered here? Focusing on the five images on the Mary Boone website, I’d say that Selma Mustajbasic is pensive or bemused; Stuart Penn offers a pugilistic pose; Tom Yendell has a stout presence; Helen Smith is almost delicate. Kiss, the only one without the model names, is chaste. But on the whole, abstract sculptures by Jean Arp say more about the body than these more-or-less Victorian figures. Flesh is not the point.

Quinn started with life casts, then had them realized in marble at full-scale by professional carvers. This effectively divorces the work from any artist craft- or skill traditions and more important, produces smooth, impersonal statues. Since the subject matter is tough for most viewers, perhaps this is necessary, yet one suspects that the distancing has more to do with style than delicacy of feeling, and with emphasizing the conceptualism of it all. After all, this is the artist who showed a self-portrait of himself carved in his own frozen blood in the “Sensation” show in 1997 at the Royal Academy in London. (“Sensation” later caused a ruckus at the Brooklyn Museum, but for the wrong reasons.)

This is not the place to rake over those old coals, but certainly it helps to know that Quinn is generally considered to be part of the Brit Pack, along with Damien Hirst. Like Hirst — and Jeff Koons, our nearest U.S. equivalent — Quinn is uneven. But when he hits, he hits real strong. He is considerably less sunny than Koons and perhaps less expansive than Hirst, but on the strength of the marble statues, I’d say he’s an artist we will continue to contend with. Sharks in tanks; floral puppies; missing limbs. Quinn has less taste.

Quinn’s marbles are not sculpture in any modernist sense. It may be surprising to read that I do not think all Greek or Roman statues are sculptures, either. Sometimes they are, but mostly they simply embody ideals and are boring formally. When statues that attempt to communicate (or impose) civic or religious ideas are also sculpturally expressive, then we really have something important. But how rare, how rare indeed, that is.

By mimicking the forms and formats of the Greco-Roman, Renaissance and neo-Classical presentation of ideal body types, but presenting bodies that have missing parts, Quinn is criticizing the idea of the ideal human body. In doing so, he slams vanity and gym culture, while celebrating the bravery of those who through birth or accident cannot achieve the historical and cultural fantasy.

Yet one cannot entirely avoid the voyeurism involved.

No doubt, Quinn is contesting beauty. Still, many will see Quinn’s statues as sensational: that is, willfully controversial and provocative. He is doing both, and the real strength of the work is the problem of the artist’s sincerity. Sincerity, thanks to Victorian cheap-sentiment, is one of those modern and postmodern taboos. Sincerity, like intention, can’t be seen. The artist’s own concept of or desire for sincerity, or the viewer’s “perception” of such, cannot count. In real life, sincerity is proved by actions, but in art there is no similar test.