DeChirico, Gladiators (1930-31)

Picabia, Minos (1930)

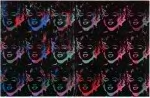

Warhol, 18 Multicolored Marilyns (1979-86)

I was once called “the peripatetic art critic” by Lawrence Alloway. Because, mid-career, he moved from London to New York, he was rather a peripatetic art critic himself. Aristotle was called peripatetic because he offered philosophical discourse while walking around. As astute readers will discern, I am hardly Aristotelian. For one thing, I attack all either/or formulations. But I do tend to walk a lot.

Looking at art is great exercise, at least in New York. Art lovers have to deal withChelsea, which, as the art zone, now stretches from the far end of the Meat Packing District to West 31st Street; 203 Chelsea galleries are listed in the Art in America gallery guide. And there’s one aspect of Artopia that no one talks about: unlike the museums, all galleries are free.

At the beginning of my Art Walk last week, I clambered up the still raw staircase to the Sperone Westwater gallery (415 W. 13th St.), the odor of meat in my nose. I really wanted to see “A Triple Alliance: De Chirico, Picabia, Warhol” (to February 21). I’ll go anywhere for Francis Picabia. It is a bit strange to see galleries, boutiques and a chic Vitro repro-modern furniture store in the middle of an active meat-butchering neighborhood. But vegetarians take heart; art real estate always drives out more plebian workplaces. Look at Soho. Where are all the sweatshops now?

The current Sperone Westwater offering easily could be a small museum show. Art historian Robert Rosenblum must have really enjoyed juxtaposing works by these three masters and thinking about how, surprisingly, the artists are alike. All three had problematic late careers, were big on socialites, and were accused of selling out.

But, let’s face it, the late Giorgio De Chirico gladiator paintings (or even the male bathhouse-bather paintings) are just not as metaphysical as his Metaphysical paintings early, early in the century. And Andy Warhol, at the other end of this game, got spotty as his cutting-edge position disappeared. Here, however, there’s the outstanding 18 Multi-Colored Marilyns (Reversed Series), 1979-86. I really do not warm to Warhol’s portraits, whether of tennis stars or dogs, but I’m sure there’s still much gold to be found. For instance, “The Last Supper” paintings, not included here, are superb, perhaps because the artist again used an instantly recognizable image.

For me, however, Picabia could do no wrong. His Minos (1929) has at least five superimposed images, and from 1942 there’s an untitled painting of two women (or maybe the same woman twice) almost obliterated with quick, dry, black brushstrokes across the canvas surface, as if in anger but not quite. No one can deny Picabia’s Dada period, but the works after those witty machines need to be looked at on their own. I think Picabia’s Dada period never ended.

Then a big walk to 22nd Street to a gallery I had not visited before. I usually make this a rule: if possible, go somewhere I have never been. Having referred to Bruce Conner in my piece on Jay DeFeo, I thought I’d like to catch up on his work. The tiny, tiny Susan Inglett Gallery is nestled inside the Frederieke Taylor Gallery (535 W. 22nd St.).

Conner, of course, did the famous film aboutDeFeo’s The Rose and several other celebrated, perhaps more film-qua-film films, including a steamy homage to Marilyn Monroe and the image-barrage called A Movie. But he’s also an artist who has made some beautifully creepy assemblage.

Now 80 years old, he’s produced four new computer-generated, poster-size prints (at Inglett until February 7). Bombhead is a military man with a mushroom-cloud head. Is the image weirdly nostalgic or is the warning still in effect? Three other prints use a field of tiny, Rorschach-like ideograms: (1) all alone, like wallpaper, in Memorial Inscription; (2) superimposed on the face of a cliff in Memorial Wall and (3) in the sky in Tracery in the Sky. But Bombhead should be on every dormitory wall.

Then I ducked into Sonnebend (536 W. 22nd St.) and was pleasantly surprised by a show of work from the ’60s by the arte povera artist Gilberto Zorio (to February 7). Zorio’s quirky, informal, yet minimal use of material is poetic indeed but now leaves one aching for myth, angst, something more. Maybe beauty is enough.

* * *

As usual I started out with a checklist of where I wanted to go, using listings and mailed and e-mailed announcements. Of course, I never get to see all the shows I target. But then there’s the chance encounter, the gallery you had not counted on: i.e., the Nancy Margolis Gallery (524 W. 25th St.). I missed the opening celebration for its new location, but there it was, on my way to Feature Inc., right on street level with some tempting art on view. Once inside I certainly liked Ferne Jacobs‘s tightly wrought, fiber vessel-forms, but the real surprise was giant ceramic platters by the Norwegian Marit Tingleff: too big to use, but hanging there as wallpieces. The largest is 61 inches wide, but my favorite, Plain with Map, is 35 x 51.

Then on to Feature Inc. across the street (530 W. 25th St.) to see what John Torreano has been up to after all these years. On view to February 14, Feature features three paintings, almost too big for the space. Made up of panels, all are implanted, as it were, with acrylic and glass “jewels” and strewn with demispheres. My favorite is DEM 106, the painting with a white ground that includes graphite or charcoal circles. But one cannot fault the two other paintings that go for a night-sky look, offering a celestial beauty while hugging the surface as you plunge into deep space.

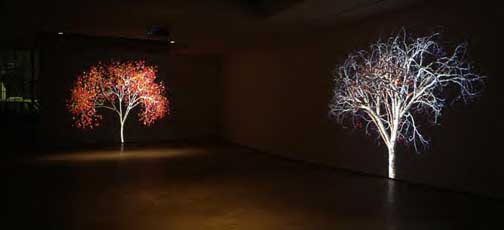

Jennifer Steinkamp, (detail) Dervish.

Then stopping here and there, bracing myself against the cold, I headed over to the Robert Miller Gallery, but passing Lehmann Maupin (540 W. 26th St.), I remembered two oddly shaped announcements they had sent. Inside, I was moved by Jennifer Steinkamp‘sDervish,giant projections of four computer-animated trees, each twirling first in one direction and then in the other. Following up this positive Muslim theme with a more critical take, in the South Gallery Sadegh Tirafkan shows photos of a bare-chested man (in a series called “Body Curves”). Tirafkan, an Iranian, has inscribed these photos of himself with Arabic letters. Hardly nude by Euro-American standards, these are meant to break the taboo on Arabic “nudity,” for, as the artist is quoted as saying, “Flesh is the canvas branded by culture.” There’s a good website with a video of the Steinkamp trees.

But if you really want to see nudes, then the new Philip Pearlstein paintings at Miller (524 W. 26th St., to February 7) should fit the bill. Pearlstein did his master’s thesis on Picabia.Was Dada an influence on one of our most celebrated realist painters? As usual, Pearlstein’s affectless but never abject models are shown deployed among various folk and popular culture collectibles.This is all in the service of the skewed, dynamic compositions that are effectively at odds with the neutralized nudes. I like best the small paintings and those in square formats. The two “Luna Park Lion” paintings are each only 33 inches square. The larger 2 Models with Hobby Horse and Carousel Ostrich (60″ square) and Model on Lawn Chair with Tin Toy Locomotive (actually a 48″ x 48″ diamond) are particularly to my liking. The squares and diamonds are powerful shapes, and making them work as a paintings is difficult indeed, for you do not have the anchoring of “landscape” or “portrait” formats. The former gives you an implied horizon to work with or against, and in the latter there’s a central axis. Painting on squares and diamonds is like working without a net — just like using the peripatetic and commentary modes in art writing.