An Identikit for Unreeling the Invisible

identikit n: (trademark) a likeness of a person’s faceconstructed from descriptions given to police; uses a set of transparencies of various facial features that can be combined to build up a picture of the person sought.

Identity politics, as exemplified by the black power, women’s liberation, and gay and lesbian movements, yielded identity art. Identity politics and identity art both started in the early ’70s. Both are responses to being identified as someone to be looked down upon, repressed, discriminated against, abused — and then turning that identification around as a source of power and pride. Both are ways of fighting back.

But what is identity? Are you your sex, your gender, your skin color, your ethnic background, your age, your nationality, your religion? Ah, if only identity were that simple. In Artopia no one is ever identified by a single identifier. Identity is a sum of characteristics. Identity is what makes you not someone else. Identity is playful; identity is what makes you interesting.

Unfortunately, identity outside of Artopia is how other people identify you when they want to point you out, beat you up, or sell you something. This in turn can become how you identify and limit yourself. You are controlled.

I have often puzzled why, although we are genetically virtually identical, there’s this awful tendency to construct minorities — to exclude, repress, sometimes to the point of slavery, torture, and murder. Competition for money, privilege, jobs, or salvation seem to be the cause. Fear is the root.

But in my darkest moments I think that some people simply like to cause misery and death and will make up all kinds of excuses to achieve their diabolical pleasures.

Not unrelated to this pleasure theory of repression is the fact that discrimination is about power. You don’t have power unless you can push people around. This explains why certain politicians can have very close gay friends (even their own children) and yet do everything possible in their political life to make life miserable for the majority of gay men and lesbians. It’s an easy way of showing their power. It’s what bullies do, so their buddies will obey. Scapegoats and foils are good to have around while you’re cheating on your wife or robbing the bank.

***

Is Nayland Blake’s “Reel Around” (Matthew Marks Gallery, 522 W. 22 St., to Feb. 21) identity art, identity politics, or something else? All three, I’d say, but with an emphasis on the last. Complexity is what makes Blake’s art stand out. Blake has been exhibiting since 1986, has curated exhibitions himself and, although there is no coffee-table book about him or October magazine celebration, he is a known art-world player. Nevertheless, unless you have some idea about what’s gone on before, the current offerings might be puzzling. (To see some thumbnails of past work, check out the gallery website.) You do, however, need to know that Blake has a white mother and a black father and is an out gay man, significant aspects of the content of his art.

Years ago, when I first met Blake, he had already made a name for himself in San Francisco with artworks that used semen and blood, I think, from h.i.v. infected men. He was thin and polite. Now, as you will see from the video pieces in his current exhibition, he is hirsute, tattooed in a major way and burly, a bear if ever there was one. “Bear” is a gay subcategory, the opposite I suppose of “twinkie.”

Since the history of recent art has fallen by the wayside, catching up with the past is sometimes necessary. You need to know there’s some precedent for art about mixed-race identity. The great piece that first comes to mind is Adrian Piper’s 1986 My Calling (Card) #1, distributed mostly at art world dinner parties. At even the slightest hint of a racist remark, she (who, like Blake, might not be perceived as African American) passed around a business card declaring her “racial”background:

Dear Friend,

I am black.

I am sure you did not realize this when you made/laughed at/agreed with that racist remark. In the past I have attempted to alert white people to myracial identity in advance. Unfortunately, this invariably cause them to react to me as pushy, manipulative, or socially inappropriate. Therefore, my policy is to assume that white people do not make these remarks, even when they believe there are not black people present, and to distribute this card when they do.

I regret any discomfort my presence is causing you, just as I am sure you to regret the discomfort your racism is causing me.

Sincerely yours,

Adrian Margaret Smith Piper

The highly regarded avant-garde novelist Walter Abish (author of How German Is It?) told me that upon his first visit to Germany, he was embarrassed by anti-Semitic remarks that his hosts made among themselves, thinking he did not understand German. A Jewish calling card like Piper’s black one might have been appropriate. I myself have often felt the need of a gay one, particularly when stepping outside the art world — but, if the truth be known, sometimes even within this protective zone.

Now, thanks to Will & Grace and Queer Eye for the Straight Guy, we are all much more sophisticated, right? But if you are made uncomfortable by the sight of two bearded men, one smeared with white frosting and the other with black frosting, kissing rather passionately for a long, long time (Coat), and the sight of a 16-foot white bunny suit (The Big One) collapsed on the floor, or the spectacle of the artist being slapped by “people with whom the artist has had a meaningful relationship, including teachers, students, and family members” on a row of monitors, you are not, I am afraid,as sophisticated as you may think.

A bunny suit? I suspect it has something to do with some childhood indignity, the reversal of Blake’s classic gingerbread house exhibited at Matthew Marks in 1998. You also have to know that not too long ago Blake made a video of himself in a bunny suit, dancing to the orders of an offscreen male voice. Was this Blake criticizing himself for masochistically trying to be white? For being worried about being heavy?

But you cannot see rabbits and not think of male fertility and promiscuity, Br’er Rabbit, Bugs Bunny, and the Native American trickster rabbit. Or, for that matter, the rabbit-in-the-moon. Europeans see the man in the moon; other cultures see an old woman. I, like Native Americans, have since childhood seen a rabbit. I don’t know what that makes me.

This begins to get closer to what I like about Blake’s art. The meanings echo and fan out. Yes, as was once a motto, the personal is political. But only if you make it so; if you make the personal into good art.

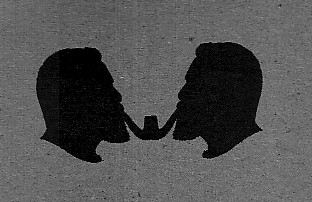

The title of the exhibition is “Reel Around.” And it certainly sets one reeling. Not yet convinced? Then I would point out the show’s logo: two identical male silhouettes, face to face, both Blake, simultaneously smoking a two-stemmed pipe. The pipe is a fine sculpture called Root. Try to unpack that.