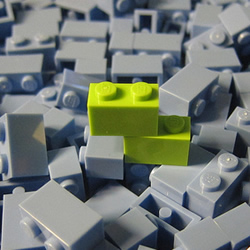

It can be comforting when a solution or a path presents itself to you as the obvious choice. When you feel comfortable moving to the next problem or question without even thinking much about the one at hand. Problem is, if you’re crafting something extraordinary, that obvious, unconsidered choice can also be damaging. It’s often drawn from habit, from ritual, from previous assumption. And great organizations aren’t built from habit.

I already wrote last week about one powerful insight from Verlyn Klinkenborg’s Several short sentences about writing. But another useful truth from the book warns against actions of habit and convenience. Says he:

You may notice, as you write, that sentences often volunteer a shape of their own

And supply their own words as if they anticipated your thinking.

Those sentences are nearly always unacceptable,

Dull and unvarying, yielding only a small number of possible structures

And only the most predictable phrases, the inevitable clichés.

He goes on to emphasize the essential and relentless work of the writer:

The writer’s job isn’t accepting sentences.

The job is making them, word by word.Volunteer sentences,

Volunteer subjects,

Volunteer structures.

Avoid them all.

In teaching and working with arts professionals, I often notice this eagerness (or resignation) to take the path that suggests itself, rather than crafting a path with relentless rigor. And in the nonprofit arts, there are plenty of solutions that present themselves: We need to be a nonprofit. We need a new mission statement. We need wealthy people on our board. We need a new logo. We need a brand reboot. We need a social media strategy. We need an Instagram feed. We need a building.

Yet, when you ask why those solutions are needed or appropriate or more immediate than any other work, the room goes silent. We need those things because they presented themselves to us as obvious, or normal, or conventional, or proper.

The cultural manager’s job isn’t accepting obvious solutions. The job is crafting them, step by step.

For an organization to produce extraordinary art and craft, in connected ways, resiliently over time, it must itself be well crafted. Managers need to address each problem in front of them with care and clarity, not rush to the next problem because the immediate problem seems obvious.

I understand that running an organization isn’t the same as writing an essay. But like an essay, the organization has a larger purpose that demands specific attention both to the whole and to the component parts. It might be worth wondering: What are the organizational equivalents of sentences that you’re crafting today? How do they fit into and amplify the arc of your larger work? And what assembly of smaller actions might make those sentences better? Further, which actions are you taking simply because they volunteered themselves to you?

As Klinkenborg warns:

Volunteer sentences occur because you’re not considering the actual sentence you’re making.

You’re looking past it toward your meaning somewhere down the road,

Or toward the intent of the whole piece.

Somehow that seems more important than the sentence you’re actually making,

Though your meaning and the intent of the whole piece

Depend entirely on the sentence you’re making.