Another Bouncing Ball: December 2010 Archives

Current practices discourage irreversible interventions. That means John Currin's work is a little safer than artists who preceded him, such as Picasso, although having the money to buy good advice doesn't guarantee it will be heeded. I know a collector who washed a DeKooning sculpture with detergent, rubbing till the surface became mottled.

The best thing about the Picasso exhibit at the Seattle Art Museum stems from its history. More than 90 percent of the 100-plus paintings. sculptures and drawings was not sold but saved by the artist and transferred after his death to the Musée Picasso in Paris, now closed for renovation. Because this material never entered the market and its care was excellent, the surfaces remain fresh. John Russell once described a painting as a "vegetable construct that changes in time." But time has barely touched what's on view till January 17 in Seattle: the evidence of the man's hand, a fusion of formal innovation and shaggy heat, his love of the body and faith in its ability to endure the tragic without losing its nerve.

Anne Baldassari, director of the Musée Picasso, selected 150 paintings, sculptures, drawings and photographs currently at the Seattle Art Museum. They illustrate the myriad-minded course of the artist's career. The result is a private tour of a public figure, Picasso as he saw himself. Credit goes to SAM for a clean installation, free of excessive wall text.

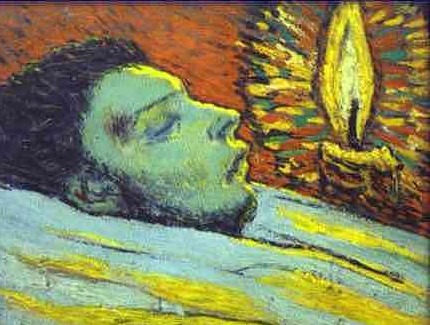

Picasso the innovator knew that art comes from art, and that painting is a visual kind of call and response. To mark the suicide of his friend, a young Picasso turned to Van Gogh. Those are Van Gogh's paint pulses radiating around the candle in Death of Casagemas from 1901, Van Gogh's color sense turned to brutally realistic purpose.

Picasso could draw with a delicacy to rival Ingres and paint to match the austere harmonies of a late Cezanne. Most of the time, the Spanish-born artist chose not to. Instead, he celebrated himself as the voracious center of a carnal universe, draping the world of the mind in the shaggy relish of physical desire.

Picasso could draw with a delicacy to rival Ingres and paint to match the austere harmonies of a late Cezanne. Most of the time, the Spanish-born artist chose not to. Instead, he celebrated himself as the voracious center of a carnal universe, draping the world of the mind in the shaggy relish of physical desire. Always there was a dialogue with other artists: Most obviously in this show, Van Gogh, Degas, Cezanne, Renoir and from closer to his own generation, Matisse.

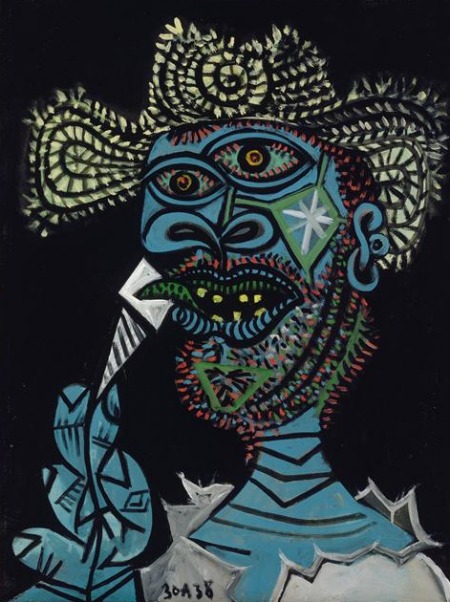

Van Gogh, again: In late summer, 1938, Picasso read that the Nazis had burned two Van Gogh paintings to demonstrate their scorn. To demonstrate his, he responded with L'Homme au chapeau de paille (Man with a Straw Hat and Ice Cream Cone), himself as Van Gogh. Wearing the Dutch artist's straw hat, he affirmed a beauty outside the realm of convention, with a lurid tongue licking the cone.

Possibly because he could afford to keep fewer paintings in his youth, the exhibit that charts his long career slights his early years in favor of his post-Cubist, robust middle and late years.

Possibly because he could afford to keep fewer paintings in his youth, the exhibit that charts his long career slights his early years in favor of his post-Cubist, robust middle and late years. For Picasso, the world was a puzzle no one can solve. Instead of searching for the final click when all the pieces fuse into place, he celebrated the off-balance, the animate, the unstable heart of motion.

As Philip Larkin so aptly observed, Being brave lets no one off the grave. Picasso explored the active life in art, the realm in which he had few peers. His work asserts that old goats can continue to cavort, and yet occasionally, limits are acknowledged. In The Kiss from 1969, an old man in the middle of seducing a young woman pauses to look past her. Instead of the familiar theme of sexual fusion, he painted the moment of drifting off, when the hero no longer remembers the lines of his play.

In his lifetime, plenty of critics found his late work dismaying. I doubt art history will agree with them. He saw himself as supreme in the most important work there is. At the end of the exhibit, SAM hung a quote from the artist, and it's a good one.

God is really only another artist. He invented the giraffes, the leopard and the cat. He has no real style. He just goes on trying other things.Through Jan. 17.

Remember its Enola Gay exhibit from 1995? The examination of this country's use of the Atom Bomb started as scholarly and turned into a my-country-right-or-wrong cheering section, after suitable pressures were applied. (A protest letter about the final product at the Smithsonian signed by more than 50 distinguished historians, here.)

And who could forget Subhankar Banerjee, whose photos of the Arctic Refuge were demoted in 2003 to the basement of the Smithsonian's National Museum of History (where they languished without wall text to identify where the photos were taken) instead of being featured, as promised, in the main rotunda? Banerjee's exhibit revealed a region teeming with life just as the Bush administration and its fellow travelers sought to depict it as what Interior Secretary Gale A. Norton called "a frozen wasteland of snow and ice."

They wanted to drill, baby, drill. Alaska's senior senator Ted Stevens called Banerjee and former president Jimmy Carter, who endorsed a book of the photos, liars. (Story here.)

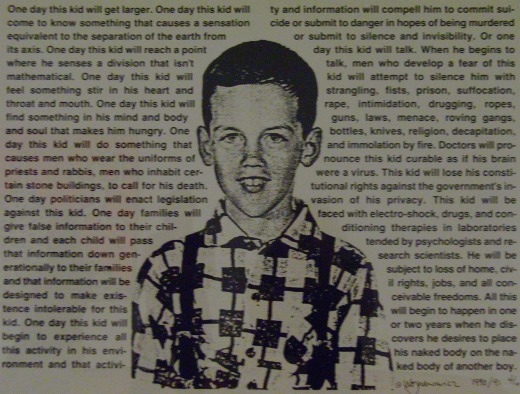

Now it's David Wojnarowicz's turn, 18 years after his death at age 37 from AIDS complications. A New York writer, painter, photographer, filmmaker, musician and performance artist, he remains one of the most singular voices not only from from the AIDS epidemic at its peak but from the inside of any marginalized and afflicted community of young people.

His four-minute video, A Fire In My Belly, was part of Hide/Seek, Difference and Desire in American Portraiture at the National Portrait Gallery until someone, anyone, complained. Naturally the Smithsonian caved. That's what it does as soon as there's a hint of political pressure. (Good summary of this most recent evidence of the institution's spinelessness here.)

His four-minute video, A Fire In My Belly, was part of Hide/Seek, Difference and Desire in American Portraiture at the National Portrait Gallery until someone, anyone, complained. Naturally the Smithsonian caved. That's what it does as soon as there's a hint of political pressure. (Good summary of this most recent evidence of the institution's spinelessness here.)Museums around the country plan to screen A Fire In My Belly, including, these in Seattle.

How is the Smithsonian reacting to pro-Wojnarowicz protests? Remarkably, its website has a big-lie announcement titled, Smithsonian Stands Firmly Behind Hide/Seek. As McGovern said about his running mate the day before dumping him, "I'm behind him a thousand percent."

For me, Wojnarowicz's best work is his writing, especially, Close to the Knives: A Memoir of Disintegration, from 1991. He knew his way around a sentence and knew how to compile them to overwhelming effect.

A few samples, from Close to the Knives:

On his home town:

It was an architecture of a population anticipating impermanence or death. It was a vacuum turning inside out, prefab materials of housing resembling the dry husks of insects halfway through their molt.On the life force:

I remembered a friend of mine dying from AIDS, and while he was visiting his family on the coast for the last time, he was seated in the grass during a picnic to which dozens of family members were invited. He looked up from his fried chicken and said, "I just want to die with a big dick in my mouth."

On infatuation:

He was the kind of guy I'd rob banks for.On death:

There were so many days of waiting for him to die the third and final time and we'd been talking to him daily because they say hearing is the last sense to go. Sometimes alone with him, the nurse outside the room, I'd take his hands and bend over whispering in his ears: hey, I don't know what you're seeing but if there's light moved toward it; if there's warmth move toward it; if you see nothing then try to imagine that one period of calm in the midst of that sky just where it reaches the ocean.On distrust:

He reminded me of a guy who'd sell you dead chameleons at a circus sideshow.On Cardinal O'Connor:

This fat cannibal from that house of walking swastikas up on fifth avenue should lose his church tax-exempt status and pay taxes retroactively for the last couple of centuries.On Jesse Helms:

I scratch my head at the hysteria surrounding the actions of the repulsive senator from zombieland who has been trying to dismantle the NEA for supporting the work of Andres Serrano and Robert Mapplethorpe.

On too much death:

There is a tendency for people affected by this epidemic to police each other or prescribe what the most important gestures would be for dealing with this experience of loss. I resent that. At the same time, I worry that friends will slowly become professional pallbearers, waiting for each death, of their lovers, friends and neighbors, and polishing their funeral speeches; perfecting their rituals of death rather than a relatively simple ritual of life such as screaming in the streets.Wouldn't it be nice if people go into the National Portrait Gallery and scream in the lobby in Wojnarowicz's honor?

In selecting the 12 artists featured in Image Transfer: Pictures in a Remix Culture, associate Henry curator Sara Krajewski looked for those whose engagements with image recycling make them visual mix masters of note, those who aren't just riding the currents but helping to steer them.

On the whole, she succeeded. Image Transfer is exactly the kind of exhibit the Henry should be doing. It has wit, depth and subtlety with an undertow of numbed tragedy. Image Transfer describes a trash world that constricts rather than enlarges upon the idea of possibility, as if we all live in a snow globe filled with images raining down on our indifferent heads, except that we too contribute to the glut.

What does the glut bring? Just as God told Moses not to look directly at the Burning Bush, Jordan Kantor suggests we refrain from direct engagement with the image world, for the same reason. Circuits will be blown, eyes burned.

Jordan Kantor Eclipse, 2009 screenprint on clear polycarbonate and silver myler sheet, and Eclipse (color inversion) oil on canvas 2009

Using flash cards, Matt Keegan's mother teaches

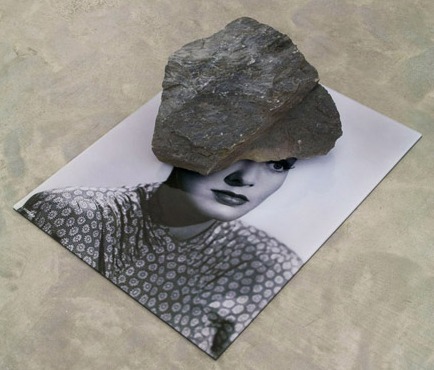

Using flash cards, Matt Keegan's mother teaches Pried from their original context, glamorous prints of dead stars move freely from screen to screen, both present and elusive, even with a rock on their heads.

Marlo Pascual Untitled, 2009, Digital print and rock

Siebren Versteeg's color-coded flags imprinted with viral pictures celebrate the dominance of unstable sign over solid sense. Karl Haendel draws a dead flow, a condensed, cluttered verison of James Rosenquist without the color or early David Salle without the S&M overtones. Sean Dack works with processing mistakes, allowing his figures to hover on the point of disintegration. (Seattle's Norie Sato did something similar in the 1970s, with paintings and videos inspired by electronic snow.) Carter Mull blurs his consumables and taints them with electronic rot.

Siebren Versteeg's color-coded flags imprinted with viral pictures celebrate the dominance of unstable sign over solid sense. Karl Haendel draws a dead flow, a condensed, cluttered verison of James Rosenquist without the color or early David Salle without the S&M overtones. Sean Dack works with processing mistakes, allowing his figures to hover on the point of disintegration. (Seattle's Norie Sato did something similar in the 1970s, with paintings and videos inspired by electronic snow.) Carter Mull blurs his consumables and taints them with electronic rot. Lisa Oppenheimer drives a stake through the timid heart of exhausted metaphor.

The Sun is Always Setting Somewhere Else (detail) 2006 Slide projection

Her critique of the banal is itself in danger of banality, as others have done similar. I like Letah Wilson's version better, not in the show:

Her critique of the banal is itself in danger of banality, as others have done similar. I like Letah Wilson's version better, not in the show:Wilson Right Back at You Digital C-print, flashlight, rocks, 42 x 30 x 46 inches, 2009

Once the image stream becomes art, there is hierarchy.

Once the image stream becomes art, there is hierarchy.In her excellent catalog essay, Krajewski enlarges upon Oppenheim's enterprise, saying she "seeks out representations of significant historical moments" but views them from the edges of their meaning. Tom Stoppard's version of this theme - Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead from 1966, has nothing to fear from Oppenheim. He still owns it, across all art disciplines. On the other hand, Image Transfer might not be doing Oppenheim justice, judging from other work available online.

This show carries itself without a lot of wall text, but I think a brief note explaining that Amanda Ross-Ho's Camera 1, Camera 2 derives from a magazine reproduction of Jeff Koons' stainless steel Rabbit from 1986. is in order. Ross-Ho shot into the shiny belly of Koons' sleek beast and played with its reflections. If you don't know that and there's no reason to suspect anyone would, the piece is a mystery.

Camera 2, digital Chromgenic print. 2007

Through repetitions, Sara VanDerBeek creates photos that aspire to be sculptures. Erika Vogt doubles herself doing different things, becoming

the detective of her own crime scene, both corpse and cop. Finally, there's Kelley Walker, who heats the cool of old advertisements.

Through repetitions, Sara VanDerBeek creates photos that aspire to be sculptures. Erika Vogt doubles herself doing different things, becoming

the detective of her own crime scene, both corpse and cop. Finally, there's Kelley Walker, who heats the cool of old advertisements.I admire how each of these artists echo and expand on each other's work, which makes the exhibit more than the sum of its parts. Many hours can be spent mulling through it. Because it is co-organized by the Henry and Independent Curators International, it is likely to travel. As such, it is an opportunity missed for the Northwest artists who could have shined in this context.

As usual, the Henry is in violation of the bloom-where-you're-planted rule. Nobody's asking for a mercy hook up, but there are at least half-a-dozen artists who could have added significantly to this show's consequence, such as Margot Quan Knight, Mike Simi, Sol Hashemi, Claude Zervas, Vanessa Renwick and Jason Hirata. It is crucial for NW artists to be seen in a larger context. By excluding them from a perfect opportunity, the Henry is missing a chance to mean more. I know that the Henry would hesitate to mount an exhibit of 12 male-only artists, even less male-only white artists. Race and sex are factors. Recognizing the artists who live here needs to be one too.

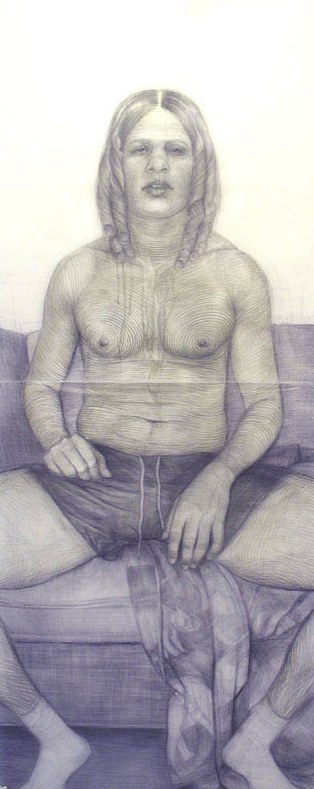

Geoffrey Chadsey

Welterweight, 2002

Watercolor pencil on rag vellum, tape

57" x 24"

Geoffrey Chadsey

Welterweight, 2002

Watercolor pencil on rag vellum, tape

57" x 24" Another great Chadsey figure with flowing locks. (Not safe for work.)

Another great Chadsey figure with flowing locks. (Not safe for work.) Lauren Grossman Behold 2003 Iron, wool, steel. 13"x21"x12" Rolls on casters.

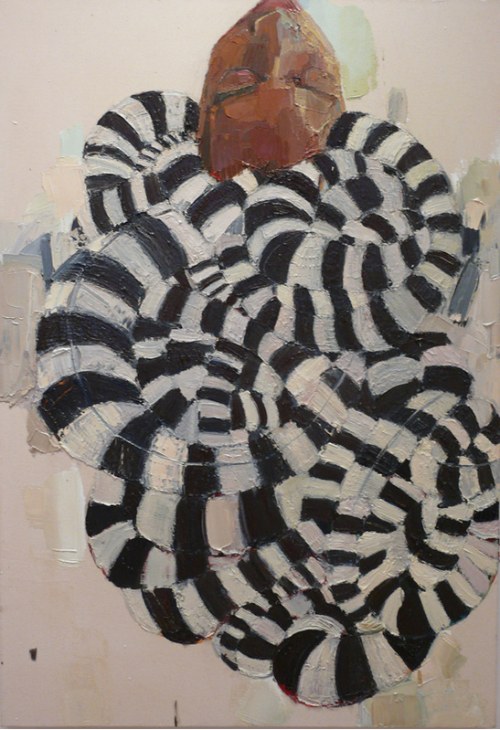

Mequitta Ahuja, again. Flowback, oil on canvas, 68"X51" 2008

Mequitta Ahuja, again. Flowback, oil on canvas, 68"X51" 2008

I think people will forget me when I'm dead. I'm going to add a codicil to my will, to forbid anybody from speaking my name.

Bill Cumming, from profile in the PI, 2005

When died of heart failure at 93 Nov. 23, he was the last member of the original Northwest School, a group of painters who brought national prominence to the region in the 1940s and 1950s. Cumming was a teenager in the circle of Mark Tobey, Morris Graves, Guy Anderson and Kenneth Callahan.

Although for reasons of health and politics Cumming didn't paint much in the 1950s, he was back by 1961 with a retrospective at the Seattle Art Museum. By 1980, he'd moved from black and gray to color, favoring what he calls sour tonalities.

More than 60 years ago, he went to a John Cage concert at Cornish College of the Arts with Morris Graves, who proceeded to heckle Cage from the audience. Because Cumming was seated next to the troublemaker, he also was given the bum's rush by ushers.

As they hustled him up the aisle, ignoring his protests that he didn't do anything, he lost his temper and decked one. Cumming was told never to return and waited for Graves in a nearby tavern.

Graves never showed up. In the lobby, he had gone limp. A Cornish trustee and doting admirer happened by and stopped the ushers from throwing him out. Graves stood up, took her arm and rejoined the concert on his best behavior.

"Graves got away with everything," said Cumming in 2005, still enjoying of the old animosities.

In her brief note marking his passing, Jen Graves made the following remarkable statement:

He was one of the last remaining links to artists like Morris Graves, Guy Anderson, and Mark Tobey. I think it's safe to say that Cumming had more personality than all those guys put together.

More personality? Is that because he was the one she met? I'd say he was the least interesting, certainly the one with the least depth. What he had was painting. Whether he was written off or, later, celebrated as the region's sentimental favorite, he stuck with what he knew and declined to enlarge upon it.

Although a lot of his work failed to rise beyond the illustrative, he has his moments. His 40-year-old formula opened up for him, allowing him to shake the stars out of the sky and light the ground under the feet of the ordinary people who populate his work - a liquid light stream filled with people.

Cumming, 2003

I'd say he was an influence on Thomas Lawson, as the link between Cumming and Lawson's recent work is so striking. But Cumming's painting rarely showed up outside the region, and never in a major venue. It's unlikely Lawson saw it.

Lawson, 2009

Cumming was born in Montana in 1917 and moved to the Northwest as a child. His father was Scottish and his mother Southern with Confederate roots. She named him William Lee, the Lee in honor of an uncle, who was in turn named after Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee.

During the Depression he was a member of the Communist Party, which he left in the 1950s, noting that the Communists were as bad as Republicans. From an extreme of a collective ideal he later moved into rugged individualism, attending EST and the Forum, the master of his own ship, the captain of his soul. His ideology at that point matched core Republicanism fantasy, and then he moved beyond it. By the 1990s, he was back in love with the Confederacy, telling James Washington Jr. (of all people) that Abraham Lincoln was the country's worst president.

Washington could be chilly to those he suspected of racism, but he only laughed. Like others who knew Cumming well, Washington didn't take his wild swings of opinion seriously. Instead, Washington trusted what he saw in the paintings, a deep and abiding good will toward all who walk the earth.

From Degas and George Herriman, he acquired his fondness for figures in motion. From Edouard Vuillard, he found the ability to use decorative patterning to potent effect.

He favored water-based media -- tempera or gouache -- and painted in layers: First the solid colors and then the patterning. He aimed for some kind of orchestrated equivalence between figures and the space around them. When the entire scene is glowing with a sour light, he was satisfied.

Cumming taught at the Art Institute of Seattle, which turns out primarily commercial artists, for more than 50 years. What he demonstrated was resilience.

I teach them to stand on their own feet and find their own style. Everybody is born with the power to draw. It's taken away from them. I try to give it back.

Cumming is represented in Seattle by the Woodside/Braseth Gallery.

Growing up as a shy kid with an overprotective mother in the Skagit Valley, Alden Mason studied bugs, watched birds become blurs in the sky and fish leap in the river. He was no good at sports because he couldn't see the ball, and no good at math because he couldn't see the blackboard. But on winter mornings he liked to stand close to cows whose breath made fat, white bursts in the air. To escape the strictures of home, he wandered into fields to smudge furrowed lines with his toe.At long last, Alden Mason is soloing at the Seattle Art Museum. SAM's assistant curator of modern and contemporary art, Marisa C. Sánchez, brought the exhibit to fruition after the departure of Michael Darling, who chose the 13 paintings from the museum's considerable Mason holdings and solicited an addition to fill a gap.

Mason, 88, has led an urban life without acquiring an urban viewpoint. His work is full of the things that moved him as a child, including the sparrows that flew around his head as he offered them carrots. While realizing that his art owes a lot to his early encounters with nature, he also credits a mail-order cartoon class. He earned the tuition by trapping muskrats. "I feel guilty about those muskrats," he said, "but I loved cartoons, with figures jumping, hopping and smooching. They were having more fun than I was. They lived in a brighter world."

Mason exhibits tend to be crowded, operating on the artist's own principle that if a little is good, more is better. This one feels open, light and full of air. More radically, it ranges across the artist's multiple styles, from 1947 to 1986, and manages to find a thread. In this show, his restlessness reads like a virtue.

It opens with his punched-up tributes to landscape painter Ray Hill in the late 1940s and his super-flat Pop abstractions in the 1960s, moves to his Burpee Garden series in the 1970s, and concludes with squiggle and scratch paintings in the 1980s.

Named for the seed catalog, Burpee Garden paintings remain Mason's greatest success -- although fumes from the oil paint, varnish and turpentine that gave the series its high-toned wet look nearly killed him and forced a move to acrylics.

From Burpee Garden, Inside Out Landscape oil/canvas 1972 oil/canvas 70 x 80 inches

Burpee Garden paintings are abstractions, his contribution to a version of post-Abstract Expressionism pioneered by Helen Frankenthaler and Morris Louis. What Mason has achieved in his paintings since then is to use a similar style of abstraction as a ground for the Dubuffet-derived figures who always populated his drawings.

Burpee Garden paintings are abstractions, his contribution to a version of post-Abstract Expressionism pioneered by Helen Frankenthaler and Morris Louis. What Mason has achieved in his paintings since then is to use a similar style of abstraction as a ground for the Dubuffet-derived figures who always populated his drawings.

Fun-loving and upbeat, Mason also is restless. When he abandoned Burpee as the series was catching on around the country, his health was the reason, but he wouldn't have stuck with it anyway. Others were enthralled, but he was getting bored. He bores quickly, changing galleries and wives, losing houses in divorces.

Even though most of his figures were born old, warped in time and oppressed by place, they kick up their misshaped legs to dance. Those without legs wave useless arms. Those missing both arms and legs rock in place, fat heads tottering on long necks. Mason's work remains improvisational and celebratory. Even when his figures signal a tragedy, the universe hums around them.

Billy 1986 acrylic/canvas 61 x 51 inches

Through Oct. 16, 2011, third floor.

Through Oct. 16, 2011, third floor.Noah Davis Bust 2 2010 Oil on canvas 36" x 36"

The past: Cranium to nose quote Picasso. To the extent that the figure resembles a squashed thing, an insect smeared on a window, there's Francis Bacon, without Bacon's sense of rage and hurt. In the future as Davis imagines it, the detachment of the dead has invaded the bodies of the living, allowing them to crumble without complaint, like sculptures in parks. Their survival absorbs them without exciting their interest. If they fail, they will not mourn their own passing.

The past: Cranium to nose quote Picasso. To the extent that the figure resembles a squashed thing, an insect smeared on a window, there's Francis Bacon, without Bacon's sense of rage and hurt. In the future as Davis imagines it, the detachment of the dead has invaded the bodies of the living, allowing them to crumble without complaint, like sculptures in parks. Their survival absorbs them without exciting their interest. If they fail, they will not mourn their own passing. Noah Davis The Future's Future 2010, Oil on canvas, 60" x 72'

I love the paint handling, the leisurely expanse of paranoid space, the orchestration of unnatural light. Davis had a gorgeous show at James Harris Gallery through Nov. 27.

I love the paint handling, the leisurely expanse of paranoid space, the orchestration of unnatural light. Davis had a gorgeous show at James Harris Gallery through Nov. 27.

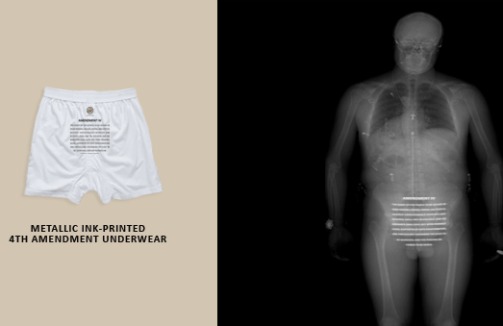

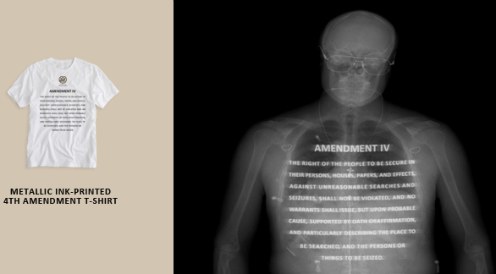

Comes in bras and panties too, of course.

Comes in bras and panties too, of course. About

Blogroll

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

innovations and impediments in not-for-profit arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

Joe Horowitz on music

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary

Recent Comments