Another Bouncing Ball: April 2010 Archives

He is not, however, only the second curator to hold the modern and contemporary slot at the Seattle Art Museum.

New York Times:

Mr. Darling's appointment reverses his last professional transition, which took him out of a thriving contemporary art environment -- the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles -- to Seattle, where he became only the second curator of that museum's modern and contemporary collection. (more)The second curator in the slot was Bruce Guenther, hired in the 1970s. He too left SAM to become chief curator at Chicago's

Between Guenther and Darling were Patterson Sims, Trevor Fairbrother and Lisa Corrin. (Sims, Fairbrother and Corrin were also deputy directors, signaling the importance the museum places on the field.) How could the NYT have disappeared four people?

Correction, please.

In years past, my visits to the Met tended to be focused. I'd pass wide swaths of world culture in a glance and on a trot. Today everything stops me: the heads and feet, swords and shields; gossamer-thin stone draperies wrapping stone bodies fresh as flower buds; cups and chairs, scrolls and silks; tombs, animal emblems and more than a millennium of painting.

Unlike the Louvre, the Met is not an airport hangar where visitors seek the great amid wide stretches of less than. The stately architecture that can handle crowds without being crowded serves collections whose breath and depth are curated into singular experiences.

I do wish, however, that the Met would stop pairing Vuillard with Bonnard, or, rather, sticking a few Vuillards in a Bonnard gallery. Bonnard poured his colored light over everything. In his company, Vuillard comes across as timid, when he is actually a deeper and more complex painter, interested in domestic suppression: how his sister fades into the wallpaper in his mother's presence, and how silence in a sitting room can fester, rattling the tea cups. I'd pair Vuillard with Munch: one scream choked, the other expressed.

Exhibits I might have missed in the old days include the drool Playing with Pictures: The Art of Victorian Photo Collage:

Kate Edith Gough (English, 1856-1948) Untitled page from the Gough Album, late 1870s Collage of watercolor and albumen silver prints; 14 5/8 x 11 5/8 in. (37 x 29.5 cm) V&A Images/Victoria and Albert Museum, London

I might not have seen Five Thousand Years of Japanese Art: Treasures from the Packard Collection. Five thousand is a discouraging time span. I tend to favor exhibits rooted in time and place, with artists who connect like balls ricocheting across pool tables: contact and motion. There's nothing but connection here, from the Neolithic to the 19th century, economy as a path toward abundance.

Kano Sansetsu (1589-1651) The Old Plum Edo period (1615-1868) 1645 Four sliding door panels (fusuma); ink, color, and gold on gilded paper

Tomb Sculptures from the Court of Burgundy

From the French High Middle Ages come 37 16-inch monks (and two boys) in a mournful procession, carved in alabaster by Jean de La Huerta and Antoine Le

Moiturier. A lucky accident of a renovation of the Musée des Beaux-Arts in

Dijon pried them out of their oranate architectural settings and set them in high relief on a table in the Met. Too bad they're going back. On their own, they are killer good: distinct individuals each in his own way awash in emotion, surely the model for Rodin's Burghers of Calais.

Given everything there is to see, who has time for Highlights from the Modern Design Collection, 1900-2006? Not me, and yet I saw it with pleasure.

Who wouldn't admire Otto Prustcher's black/white checkerboard plant stand, zig-zagging across space, from 1903; Harold Van Doren's ode to motion, his Snow-Place Sled, from 1934; Charles and Ray Eames' Buffalo Chair, from 1946; Lucas Samaras' plaster, falling-apart chair, from 1969-70, and Dale Chihuly's Speckled Gold Venetian with Cobalt Leaves and Stems, from 2001.

There's been a lot of talk in Seattle recently about a proposed Chihuly Museum at Seattle Center, much of it implying he's some kind of lowest common denominator huckster, not a real artist at all. I looked in this show for anybody else from the Northwest who'd made the cut. Who else shared the honor? Nobody. Take it to the bank, nay-sayers. Your account is empty.

On a recent Saturday, a woman behind me in line to get into MoMA said, "I hate the young." She was assuming they were there en masse to see the museum's grotesque hagiography of Tim Burton (every scrap preserved). If true, they didn't limit themselves to the man who made a mockery of Sweeney Todd but poured out into other galleries, their numbers mitigating against anyone's engagement.

Obviously, the problem is not the young but the museum, which needs to determine what is a sustainable number and what is a stagnating overflow. People were four or five layers deep in the Cartier-Bresson. Who can see his immaculate, small prints in such a physical cacophony? Full of respect for those who forged ahead, I gave up, thinking of Yogi Berra: "That place is so crowded, nobody goes there anymore."

In such a mob scene, the courage of Marina Abramovic's performance retrospective, The Artist is Present, is overwhelming. She's there every day, all day long, as members from the audience in three minute increments take a seat in front of her and lock into the energy of her presence. Surrounding them is a parted sea of humanity hushed by her intensity.

What a dazzling exhibit. (Hats off to curator Klaus Biesenbach.) Performance retrospectives are a difficult breed of cat. If you missed the originals, you're limping along afterward with description, analysis and documentation impersonating the real thing. Instead, with fifty works spanning four decades (including sound pieces, excellent videos and photographs), this exhibit recreates a number of her major pieces by restaging them with a frequently nude cast of others. (They deserve bravery badges too.)

Back to the audience, swollen into a problem for itself. It's an enormous hurtle for Abramovic, who either makes contact or makes nothing. Even with thousands around her, she succeeds, both in the galleries and in the atrium where she presides, inspiring many who signed up to sit down with her to cast off their public shell and give her something back.

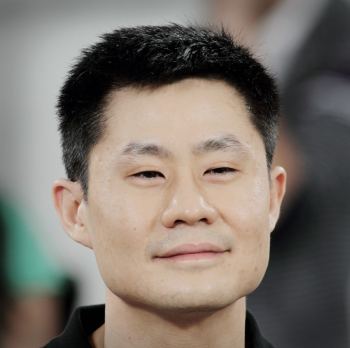

Marco Anelli's photographs of the sitters on flickr are a record of the audience as artists, sharing what they are capable of sharing with the woman in front of them. (Via) I love these faces. Hearts open.

Through May 31.

Tim Burton's last day is Monday, which will undoubtedly thin the herd. What will be left is the chill of the architecture. There is no grace in the new space.

Also managing to triumph over crowds in a chilly surround is William Kentridge: Five Themes, organized by Mark Rosenthal for the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and the Norton Museum of Art.

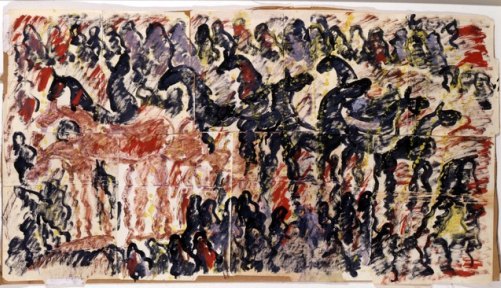

In prints, charcoal drawings and animated films based on charcoal drawings, he surveys the human predicament. I wish I'd seen this show in San Francisco. Here, the videos dominate, as the drawings are tough to see cheek to jowl to baby carriage with others. He calls his cut-out drawings of shadow puppets stone age. Across a rocky terrain they come, carrying their plows, their parents, their prisoners, their party props and weapons. It's human history in motion: The fleet, the lame, the guilty and innocent, burdened by their sick and their dead. In the middle of it all, a real human eyeball pops up, and later a real cat. Shadows enlarge, dissolve and double into shadows of shadows, stories lost and found; the dynamic, overlapping chaos of history.

Through May 17.

Down in the basement, Marilyn Minter's video, Green Pink Caviar from 2009 drew a cluster of the gorgeous young. Watching them watching, it occurred to me that Abramovic, Kentridge and Minter are all from my generation. The young look great, but they'll have to work hard to catch us.

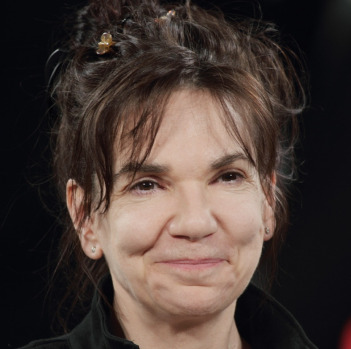

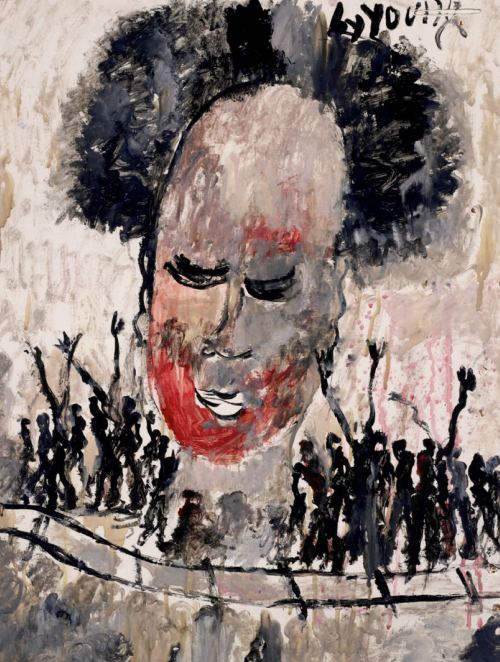

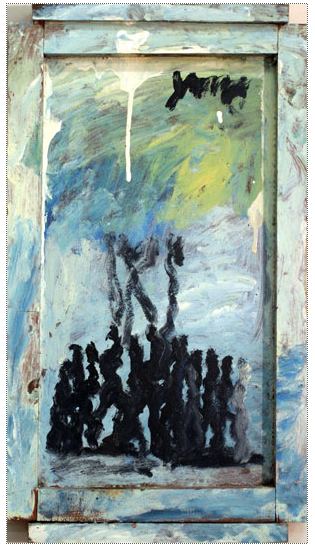

From Purvis Young's obituary in the New York Times:

He lived most of his life in the Overtown section of Miami, a once-thriving community that was ravaged by the construction of an interstate highway through it in the 1960s, and he painted what he saw around him.Artists are the bloom that blight cannot kill.

Image via:

Images via:

Images via:

I'll be walking on the right. Will continue to post, although I'm using a laptop for the first time and might fail to figure it out. (Into every life progress comes, however haltingly.)

I'll be walking on the right. Will continue to post, although I'm using a laptop for the first time and might fail to figure it out. (Into every life progress comes, however haltingly.)OSCAR TUAZON "BLACK HOLE" 2003 Newspaper, tape, paint 250 x 900 x 600 cm Edition: 1

Not in Rock Hushka's The Secret Language of Animals at the Tacoma Art Museum:

Encrusted over the

surface of Markovitz's fiberglass molds, gourds and papier mache are

many

thousands of tiny glass beads woven into streams of colored light and

bordered with oil paint, leather and velvet, foil and nails, amulets and

jewels.

All that complexity becomes a simplicity in its realization.

Her sculptures are presences that come from time slowed down. Her deer

and bear heads aren't trophies but relatives, linking us to all beings

who lean into light and live by breath.

Encrusted over the

surface of Markovitz's fiberglass molds, gourds and papier mache are

many

thousands of tiny glass beads woven into streams of colored light and

bordered with oil paint, leather and velvet, foil and nails, amulets and

jewels.

All that complexity becomes a simplicity in its realization.

Her sculptures are presences that come from time slowed down. Her deer

and bear heads aren't trophies but relatives, linking us to all beings

who lean into light and live by breath.In the Northwest on this theme, she is too big to ignore. Ignoring her becomes a statement, and that statement serves as the elephant in the room, invisible but determinative, sour and eccentric.

Hushka's exhibit is still a pleasure. (My review here.) The more time I spent in it, however, the stronger became the conviction that a good effort could have been a great one, given certain additions and a lot of deletions. The exhibit wants to be all things to all people. Hushka is too good a curator not to know that he padded in the interests of popularity. A starker survey would give the exhibit's core samples a chance to reverberate in each other's company.

First, almost everything made before 1960 needed to go. In this show, contemporary art sets the tone. With the sole exception of Audubon's hand-colored engraving, Three-Toed Woodpecker from 1832 (a perfect accompaniment to Justin Gibbens' present day riffs on it), the mostly modest art from earlier eras needs its own space in another show. Most of these prints and small paintings function as florid digressions in sentences that want to be muscular.

Second, Joey Kirkpatrick and Flora C. Mace's eight cast glass sculptures from Bird Pages are a dead spot where the ball won't bounce, far from their best work. One might have slipped by, but twelve?

Another big chunk that needed to go: Just say no to the corny, fey, conventionally literal and the whimiscal.

Had the muscular been achieved, there are a few possible additions that could have augmented it, besides, of course, the essential Markovitz. The ones below would have been easy to get in Tacoma, not, in other words, the impossible dream.

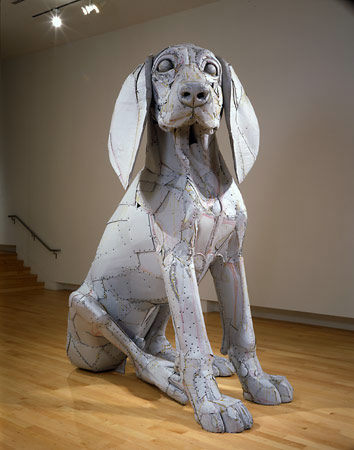

TAM owns Scott Fife's LeRoy, 2004. 118 x 78 x 120 inches, archival cardboard, glue, screws.

Of course it belongs

where it is, in the exhibit, but it would have been swell to offer a darker

side of Fife as well, something less ingratiating than the dog that

normally sits as a greeter in the lobby.

Of course it belongs

where it is, in the exhibit, but it would have been swell to offer a darker

side of Fife as well, something less ingratiating than the dog that

normally sits as a greeter in the lobby. The

touch of the mythological would not have gone amiss.

The

touch of the mythological would not have gone amiss.Michael Spafford The Iliad #19 woodcut, 2004 image 12 x 20", paper size 19¾ x 26"

I

would have appreciated something from the heart of old Hollywood.

I

would have appreciated something from the heart of old Hollywood.Grant Barnhart, Elizabeth Taylor, acrylic on canvas, 12 x 12 inches

An animal-in-art exhibit is a good place to explore

the anguish of

childhood.

An animal-in-art exhibit is a good place to explore

the anguish of

childhood.Pat De Caro, Toilet with Snake, oil/glassine, 2003 42 x 40"

How about touching on the theme of the kinks in the Wild West?

How about touching on the theme of the kinks in the Wild West?SuttonBeresCuller Beast of Burden II 2003 C-print on Sintra 18 x 24 inches Edition of 5

Every exhibit is a

series of

moments. In great ones, the moments cohere into an overwhelming

conclusion. Hushka's had the makings of great but settled for pleasing,

well below his capabilities.

Every exhibit is a

series of

moments. In great ones, the moments cohere into an overwhelming

conclusion. Hushka's had the makings of great but settled for pleasing,

well below his capabilities. Through June 27.

Yoko Ott would prefer a botanical garden. Alas, we have one already and can't afford to take care of it. (If ifs and buts were candies and nuts, what a Merry Christmas we'd all have.)

To wit:

To wit: The City of Seattle is scrambling to cover a multimillion dollar budget deficit. Now, people close to the situation say Parks and Recreation will take the biggest hit, with first cuts planned as soon as July, according to the Associated Recreation Council, an independent non-profit that partners with the city department. "Community members need to share their personal stories with the Mayor and City Council members if they expect the doors to stay open and the parks maintained," said Christina Arcidy, Project Coordinator for ARC, in an e-mail sent to CHS. "There are no public meetings or formal requests for public comment, so individuals must reach out to their elected officials and start a dialogue if they want to have an impact." Cuts could include lawn and mowing maintenance for all Seattle parks. Pools and public facilities in all parks, including Volunteer, Cal Anderson and Miller Parks, will not be open to the public any longer, or may have shorter operation hours. While none of the major planned cuts have been confirmed by Parks or the city, CHS received confirmation from a City employee with knowledge of the situation who asked to remain anonymous about the severity - and certainty - of the cuts being planned. (more)Surely better times await, and then we'll be stuck with a Chihuly center, right? Well, wrong. The privately funded venture would have a 5-year-lease. If Chihuly fails to dazzle the public (and bring in from $300,000 to $500,000 annually to city coffers), his glass plug can be pulled, leaving the building that's already there and a garden. (Even if he's a raging success, the lease will terminate at 20 years.)

For these reasons and so many more, anti-Chihuly forces, please continue to fight the good fight. Save cracked asphalt for the kids. They'll thank you when they grow up to be disaffected hipsters. I for one admire your moxie and your effectiveness. The mayor sounds as if he's leaning toward siding with you, as well he should. You helped elect him.

In the meantime, Bobby D. has the closer:

Here comes the blind commissioner

They've got him in a trance

One hand is tied to the tight-rope walker

The other is in his pants

And the riot squad they're restless

They need somewhere to go

As Lady and I look out tonight

From Desolation Row

Rathman creates his own rumble in the jungle: drawing vs photos, drawing vs film. Drawing wins.

Zaire: David Rathman Project - Muhammad Ali Rumble in the Jungle 1974 from Tom DeBiaso on Vimeo.

If you were going to get a pet

What kind of animal would you get?

A soft-bodied dog, a hen

Feathers and fur to begin it again

when the sun goes down and it gets dark

I saw an animal in a park

Bring it home to give it to you

I have seen animals break in two

You were looking for something soft

And loyal and clean and wondrously careful

a form of otherwise vicious habit

could have long ears and be called a rabbit

Dead died will die want

Morning midnight I asked you

What kind of animal would you get?

Robert Creeley

The Secret Language of Animals is not a secret. Instead, the exhibit of that title at the Tacoma Art Museum is almost entirely about us. Ever since humans stood up to look around, we've made images of animals as shipping containers addressed to ourselves. From the bull on the wall of a cave to the shark in a gallery, it's a myriad-minded stream of us projecting into them.

The stream never ends, and neither does our interest. Through animal depictions, human consciousness parades. As a theme, it's a hearty perennial, hard to kill. The good news is, Tacoma doesn't. Curated by Rock Hushka, The Secret Language is, like his currently running A Concise History of Northwest Art, a winner.

Unlike A Concise History, however, The Secret Language is a baggy monster, drawn from the museum's collection and beyond it, from the 19th century to the present. From its title to the structure of its categories arranged in zoo fashion, like with like, Hushka's attempt to order his offerings fails to convince. What saves this exhibit are the objects in it. There are too many of them crammed together, but the grace and force of their diversity creates a gravitational pull of interest that sweeps the audience along.

There are three giant Deborah Butterfield's in one spacious gallery. Her horses are drawings in space. The best are lumbering but light, well bred from wreckage. These three are fine indeed. Why didn't the museum give her the entire gallery? The small prints on the wall (Stubbs, Delacroix) are hedged bets. Hello Tacoma Art Museum: If you're highlighting an artist, go ahead and give her the space. If she needs Stubbs to matter, she doesn't.

Vanessa Renwick Longhorn, 2010 16mm to video loop shot at Patty Pink Chap's Ranch in Montana, from the Oregon Department of Kick Ass

Renwick's Longhorn is a rarity, a piece about an animal that offers nothing but the animal. Bill Viola's buffalo breathing steam in the morning is an emblem of spirit, but Renwick's shaggy star offers only itself. No meaning beyond its own adheres. With an economy of motion that makes sense in one so heavy-headed, it stares, turns, grazes and steps to the side, over and over in a repeating loop. It's a massive utterance on a wide plain, and it has nothing to say to us.

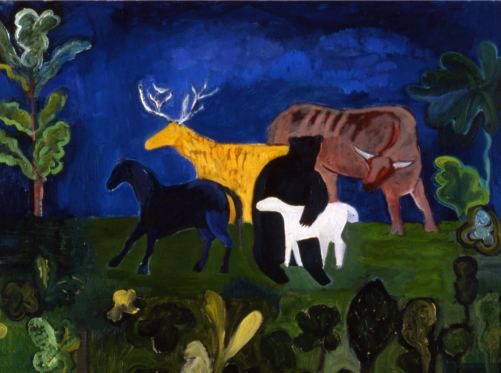

Renwick's Longhorn is a rarity, a piece about an animal that offers nothing but the animal. Bill Viola's buffalo breathing steam in the morning is an emblem of spirit, but Renwick's shaggy star offers only itself. No meaning beyond its own adheres. With an economy of motion that makes sense in one so heavy-headed, it stares, turns, grazes and steps to the side, over and over in a repeating loop. It's a massive utterance on a wide plain, and it has nothing to say to us.Elizabeth Sandvig's Peaceable Kingdom series was inspired, of course, by Edward Hicks. Unlike Hicks, she has no hopes of lions lying down with lambs, but she likes the lights and darks of their colored shapes and suggestive densities. Instead of family, the deer is as distant as the sun, and the black bear with a possessive paw on the flank of a sheep cannot be trusted.

Sandvig, Peaceable Kingdom at Night, 2003 oil/canvas 24 x 32 inches

Soaring past William Wegman's dress-up dogs is Fred Muram's eating breakfast. The artist calmly dips his spoon around his dog's lapping tongue and eats as if there's nothing odd in doing so. He's Buster Keaton who sees the train coming but doesn't leave the tracks. Muram divides the world in two: those who know a train with a tail won't hurt them and those who are fearfully freaked out.

Soaring past William Wegman's dress-up dogs is Fred Muram's eating breakfast. The artist calmly dips his spoon around his dog's lapping tongue and eats as if there's nothing odd in doing so. He's Buster Keaton who sees the train coming but doesn't leave the tracks. Muram divides the world in two: those who know a train with a tail won't hurt them and those who are fearfully freaked out.Muram Sharing a Bowl of Fruit Loops with My Dog, 208 Single channel video Dimensions variable

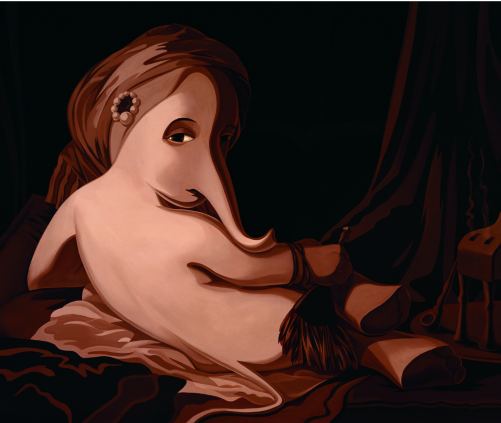

In monochromatic sepia, Joseph Park's The Grand Odalisque takes

Ingres' boneless paintings of nude women (all flesh, little

structure), and sets not only the figure but the ground

around it in motion. Curtain, bed, tassel, turban, tail and trunk have a seamless flow. It's a lost time looked at again with humor and a

strange, silky gravity.

In monochromatic sepia, Joseph Park's The Grand Odalisque takes

Ingres' boneless paintings of nude women (all flesh, little

structure), and sets not only the figure but the ground

around it in motion. Curtain, bed, tassel, turban, tail and trunk have a seamless flow. It's a lost time looked at again with humor and a

strange, silky gravity.Park, The Grand Odalisque, 2001 oil/linen 30 x 36 inches

I'm not sure that Malia Jensen's bronze bear would matter much without its title. With it, the animal is the epitome of a guilty party, confessing only when caught.

I'm not sure that Malia Jensen's bronze bear would matter much without its title. With it, the animal is the epitome of a guilty party, confessing only when caught.Jensen, Is This Your Cat? 2006 Bronze 22 x 14 x12

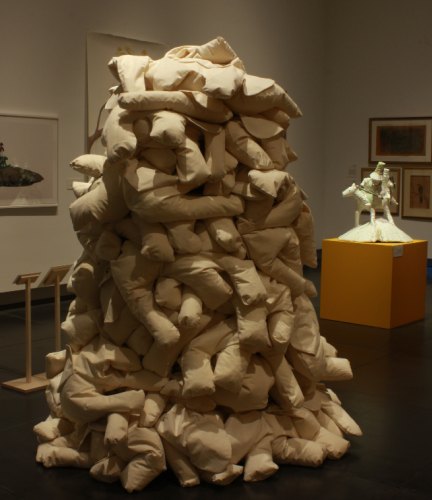

Hats off to Hushka for recreating Jeffry Mitchell's elephant pile from 1990, sewn by Tacoma Art Museum volunteers. Let's hear it for battered hopes and dreams, for what goes soft and slack and lies discarded in a sweet heap.

Hats off to Hushka for recreating Jeffry Mitchell's elephant pile from 1990, sewn by Tacoma Art Museum volunteers. Let's hear it for battered hopes and dreams, for what goes soft and slack and lies discarded in a sweet heap.Mitchell, The Pile of Elephants, 1990 recreated 2010 Muslin and Styrofoam, 114 x 108 x 108 inches. (Claire Cowie's Villagers on Horse, 2004-05 in the rear)

Richard Hart paints marsupial girls.

Richard Hart paints marsupial girls.Hart The Poetic Truths of High-School Journal Keepers, 2009

Maki Tamura's painted paper constructions can be overworked. Not this one, whose image fails to do it justice. The incredible lightness of its being evokes Fragonard.

Maki Tamura's painted paper constructions can be overworked. Not this one, whose image fails to do it justice. The incredible lightness of its being evokes Fragonard.Tamura Circus 2009 watercolor paper

Geoffrey Chadsey's paintings cannot be reproduced. Missing is the queasy subtly of the shading, the face and chest whorled like diseased tree rings, the way the small dog is actually more of a rat resting on the root of a cadaverous man.

Geoffrey Chadsey's paintings cannot be reproduced. Missing is the queasy subtly of the shading, the face and chest whorled like diseased tree rings, the way the small dog is actually more of a rat resting on the root of a cadaverous man. Chadsey Pet 2010 watercolor pencil on Mylar

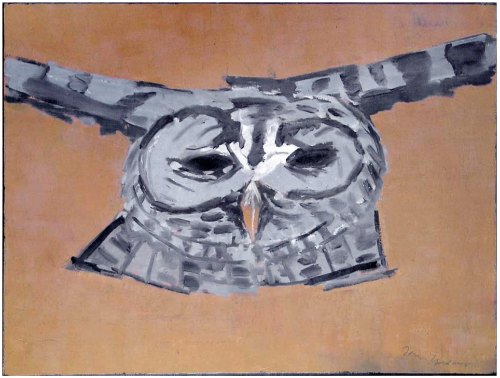

Air, desert, blue owl:

Air, desert, blue owl:Joseph Goldberg Chaco 2005 encaustic on linen over wood 36 x 48 inches

Nice to see Justin Gibbens' birds hanging with one of Audubon's, their source. Also worth the trip in this show are the Joan Brown's, Muarizio Cattelan's taxidermized dog sleeping in a chair (Good Boy, 1998); Morris Graves' Walking Bird, 1943; John Baldessari's Two Onlookers and Tragedy (With Mice) 1989; Kenneth Callahan's dragonfly, late 1950s; Nole Giulini's Mickey Mouse Organ, from 1994, several Claire Cowie's, and Alden Mason's Polka at the Public Market, 1987.

Nice to see Justin Gibbens' birds hanging with one of Audubon's, their source. Also worth the trip in this show are the Joan Brown's, Muarizio Cattelan's taxidermized dog sleeping in a chair (Good Boy, 1998); Morris Graves' Walking Bird, 1943; John Baldessari's Two Onlookers and Tragedy (With Mice) 1989; Kenneth Callahan's dragonfly, late 1950s; Nole Giulini's Mickey Mouse Organ, from 1994, several Claire Cowie's, and Alden Mason's Polka at the Public Market, 1987.Post to follow: the downside.

With 10 (or is it 8?) journalists replacing a staff of around 200, the PI continues online as a delusion of itself. This shallow but sprightly mirage continues to attract traffic. In doing so, it's shaping up to be a financial success and a journalistic disaster. Why should publishers continue to pay (and put up with) writers, photographers, editors, artists and support staff who expect real salaries and health insurance, not to mention vacations and sick leave? Now there's an alternative: a bare bones group with a bare bones compensation. What they can't cover in their overheated work day can be covered by freelancers. The new meaning of freelance means you work for free.

The anniversary of the PI's demise drew comment from former staffers. One thing you can say about journalists. They continue to type, even after their platform is gone.

One of my favorite PI reporters, Andrea James, now works in finance. From her new dollars and cents perspective, she finds her old paper lamentable. Her blog post, A well-run business it wasn't, argued just that. What she left out is everything that mattered. In spite of shrinking resources, the PI that folded was the best version of itself in my more than two decades of employ there. The infusion of tough-minded young staff inspired those who'd been jogging in place to walk back into the world of who/what/when/where/why. The PI had the best chief editor I'd ever worked for, David McCumber, and a sane publisher, Roger Oglesby. (Sane publishers were not a given at the old PI.)

The wrong paper folded, leaving the fat-cat Seattle Times. Fine reporters work there, but the culture is one of Panglossian self-congratulation. Unless you piss Kool-Aid into the cup, you won't be hired. To secure a slot you have to be blind to the egregious faults of the right-wing bully in charge, Frank down-with-death-taxes Blethen.

Nobody had to swear allegiance at the PI; in fact, skepticism was prized. A good newspaper is not a religion. Leaps of faith are discouraged. Instead, there is the daily hunt for big-game facts, for stories that are as accurate and fair-minded as the humans producing them are capable.

Where are we now?

What I think of as the PI Brain Trust is operating online as Investigate West, run by the great Rita Hibbard. The Seattle Post-Globe has turned into a good local news source. Plenty of former staffers have blogs, and the Post-Globe links to them, including my own.

A recent addition to the former PI staff blog roll is D. Parvaz's well-named Something to Say. Fresh from a Neiman, she's an Iranian-born Maureen Dowd: an enemy of cliche and advocate for clear thinking. I hadn't realized how much I missed her voice until I started reading it again. Referring to new research on suicide bombers, she wrote:

A recent addition to the former PI staff blog roll is D. Parvaz's well-named Something to Say. Fresh from a Neiman, she's an Iranian-born Maureen Dowd: an enemy of cliche and advocate for clear thinking. I hadn't realized how much I missed her voice until I started reading it again. Referring to new research on suicide bombers, she wrote:As it turns out, strapping a bomb to oneself and killing others in the process of detonating it isn't anyone's first choice.Thought that Allah and the 49 promised virgins covered the topic? Reading Parvaz will take your mind to the gym. Her blog is my one-year anniversary present to myself, evidence that my peeps are everywhere, doing good work.

An exquisite example of the hotness-and-buzz genre is Tim Appelo's Charlie's Charge in City Arts Magazine, Seattle edition. I appreciate

Appelo:

Why is Seattle's most-buzzed art scene in Ballard instead of Pioneer Square? Only one Seattle gallery sent artists to December's big Miami art fair (sic: Ambach & Rice was at NADA), and only one in the whole Northwest went to last month's New York Armory Show: Charles and Amanda Kitching's Ambach & Rice in Ballard. "Howard House had it, James Harris had it, Scott Lawrimore has had a long run," says one gallerygoer. "Now Charlie is the new hot thing."Galleries are like Darwin's finches. Those who find a niche are the most successful. Beyond that, whether Ambach & Rice is in Ballard or Pioneer Square, it's part of the small community of Seattle art dealers who represent artists who matter.

Back to Appelo's article. Ambach & Rice did not "raid" another gallery. What are artists in this construction, the loot? The artists in question came to the Kitchings, not the reverse. Then there are the personal remarks:

Charles Kitching has got youth, sharp looks, savvy and savoir faire. So some resentfully dismiss him as "Charlie Ka-CHING!"That's two anonymous quotes from the school of buzz. Unless there's a compelling reason, everybody in a story should be on the record, including the casually snide.

Not that everybody on the record scored this time out. Assuming Portland dealer Elizabeth Leach was quoted fairly (I am going to assume that, given Appelo's solid record in journalism), she offered a great example of double-speak: the official position first, followed by what she really thinks.

"It's easier to be jealous," says Leach, "but it makes more sense to be supportive. Northwest galleries that go to fairs are ambassadors for all of us." She does think hard times have made the Armory "less competitive. One could get into the Armory if one applied."Who is this "one" who could get into whatever fair one wanted?

Appelo appears to take a similar position:

How come other galleries didn't go to the Armory Show? One reason is money. "It costs easily twenty to thirty thousand dollars to go," says top Portland gallerist Elizabeth Leach.One reason is money. Appelo doesn't mention any others. Assume for a moment you're a high school senior with a B average. You're considering Podunk U or Harvard. One reason you're not going to Harvard is money. Can anybody think of another?

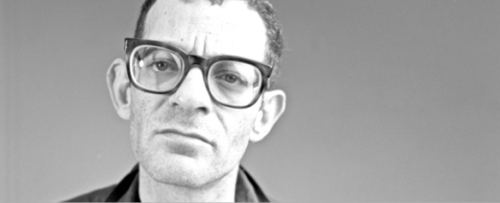

Speaking of himself in the third person, Jesse Bernstein once noted that he was "unemployed until the age of six; since then he has worked as a seeing eye dog for the spiritually impaired and as an emergency storm drain." Poet, performance artist, playwright, actor and friend of what he called the expendable people, he killed himself in 1990 in Neah Bay at age 40.

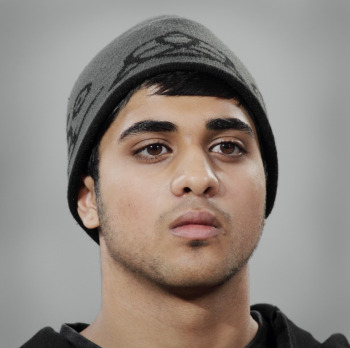

Photo Alice Wheeler

Most of his friends remember him not for his tragedy, which included mental illness, alcoholism and drug addiction, but for his talent, his generosity, his steadfast loyalty and gleeful charm when the debilitating fog of illness lifted.

Small with bow legs and tattoos running up his arms, Bernstein had a

gravelly voice that became slurred when he neglected to put in his teeth

for his late-night phone calls to many willing and semi-willing

listeners.

They rarely needed to say anything. On the phone he said it all, ranging

across the history of poetics, the crimes of the Central Intelligence

Agency, the need for cheaper breakfast cereal and the search for a

sustaining form of God's grace.

Most of his friends remember him not for his tragedy, which included mental illness, alcoholism and drug addiction, but for his talent, his generosity, his steadfast loyalty and gleeful charm when the debilitating fog of illness lifted.

Small with bow legs and tattoos running up his arms, Bernstein had a

gravelly voice that became slurred when he neglected to put in his teeth

for his late-night phone calls to many willing and semi-willing

listeners.

They rarely needed to say anything. On the phone he said it all, ranging

across the history of poetics, the crimes of the Central Intelligence

Agency, the need for cheaper breakfast cereal and the search for a

sustaining form of God's grace.A well-edited collection of the range of his best work has yet to appear, although a posthumously released Sub Pop CD titled Prison briefly lit up the charts after selections from it played over the open sequence of Oliver Stone's Natural Born Killers.

Peter Sillen's recently completed documentary on Bernstein, I Am Secretly An Important Man, opens at The Full Frame Documentary Film Festival in North Carolina on Friday. It will screen as part of a Creative Capital film festival at the Museum of Modern Art on May 15 & 27. Sillen is still working on a Seattle release.

More Noise Please!

I live on a street

where there are many

many cars

and trucks

and factories

that pump

and bang and

grind all night

and day.

It is a miracle

that I can write poetry

or sleep or

talk on the telephone

or that

my lover will

visit me here.

January, 1997. Oil on canvas, 78 x 95 ½ inches.

How brilliant it would have been to pair it with a Kenneth Callahan clear cut from the 1930s. Brophy has the sky drifting across mud furrows, the mountains serene in the distance and the exposed face of a cut tree shining low like a setting sun, but Callahan has the forest world convulsed, with no reassuring grace notes.

How brilliant it would have been to pair it with a Kenneth Callahan clear cut from the 1930s. Brophy has the sky drifting across mud furrows, the mountains serene in the distance and the exposed face of a cut tree shining low like a setting sun, but Callahan has the forest world convulsed, with no reassuring grace notes. The Tacoma Art Museum does not have such a Callahan in its collection or it would have made an appearance. (Nor could I find one online.) Organized by the museum's senior curator, Rock Hushka, A Concise History draws entirely from the museum's holdings, which are impressive in their range and depth. Instead of a Callahan, what hangs beside Brophy is a meek Sidney Lawrence, probably from the 1930s, Mt. McKinley, Alaska, doing Lawrence no favors.

Hushka would have been well advised to give Brophy the entry wall. Experiences on the same frequency tend to fuse or spark. Lawrence is overwhelmed and deserves better. (His own space or a more sympathetic companion could have brought out his subtle delicacies.)

What a smart title. The word concise tends to cut off the inevitable complaints: Why not x? Surely if you have y, you need w. My only real compliant is that Huska didn't take the word seriously enough. Exhibits at the Tacoma Art Museum tend toward salon style. They're packed to the rafters. While I enjoyed this show, its density overwhelms the particular with the general.

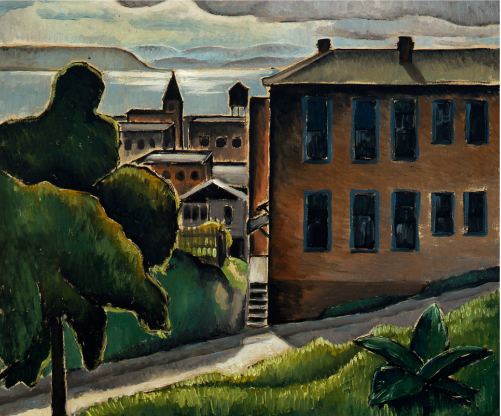

I like the exhibit's first half of the 20th Century, which favors the lesser knowns, such as Ambrose Patterson, Peter Camfferman, Charles Heaney (It's worth a trip to the Portland Art Museum to see the Heaney's, lamentably underrepresented in Seattle), Walter Isaacs, Zama Vanessa Helder and Kenjiro Nomura.

Kenjiro Nomura, Puget Sound,1933. Oil on canvas, 19 5/8 x 23 ¾ inches.

With light rimming his forms, Nomura conveys a quiet kind of Surrealism that predates Wayne Tiebaud's. With painter Kamekichi Tokita, Nomura ran

a sign-painting business before the war. In the 1930s they managed to give some work to Paul Horiuchi, who remembered painting large hula dancers and octopuses on billboards for them. The three would go out sketching on Sunday afternoons.

By the late 1930s such excursions were no longer safe. Horiuchi said he

and Nomura were on the University Bridge one day, drawing together, when

somebody reported them to the police as suspicious characters. After

investigating, the police told them to stop sketching outside.

With light rimming his forms, Nomura conveys a quiet kind of Surrealism that predates Wayne Tiebaud's. With painter Kamekichi Tokita, Nomura ran

a sign-painting business before the war. In the 1930s they managed to give some work to Paul Horiuchi, who remembered painting large hula dancers and octopuses on billboards for them. The three would go out sketching on Sunday afternoons.

By the late 1930s such excursions were no longer safe. Horiuchi said he

and Nomura were on the University Bridge one day, drawing together, when

somebody reported them to the police as suspicious characters. After

investigating, the police told them to stop sketching outside.Nomura and Tokita were deported to camp Minidoka in Idaho, and neither managed to regain their stride as artists afterward. Nomura had a lovely, dreamy style before the war, turning Seattle into his own kind of paradise. With their loose, sensuous line, his softly colored hedges and buildings seem to be only pausing in space before floating away.

(For more on the theme of Seattle's Japanese -American artists of the World War II generation, see review of Barbara John's Views and Visions at the Seattle Art Museum in 1990.)

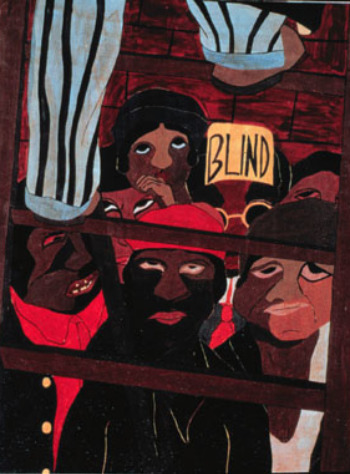

The thing about major figures, however, is that they tend to dominate. Morris Graves and Jacob Lawrence own the first half of this exhibit's the 20th Century. Claiming early Lawrence for Northwest art is a stretch, as he didn't move to the region until 1971, when offered full-professor tenure at the University of Washington.

Jacob Lawrence, Street Orator, 1936

When you've got it, flaunt it. The Seattle Art Museum does not own a Lawrence as good as this one.

When you've got it, flaunt it. The Seattle Art Museum does not own a Lawrence as good as this one. Graves' Chalice Holding the Stimson Mill, also from 1936, has the kind of fierce, light-struck landscape furrows that rival Anslem Kiefer's, in deeper and far more radiant hues. Early Graves struck his colors like a gong, and they continue to reverberate.

The Mark Tobey here (Point of Intersection, 1949) is fine if a little academic, but representations of Guy Anderson and Callahan should have been left in the bins. Getting better Andersons could not be the impossible dream.

Rounding out the 20th-Century's first half is Spencer Moseley's Olympia Landscape from 1947. Moseley is best known these days for arranging the Jacob Lawrence hire at the University of Washington, but what a lively painter he was. This painting does not even hint at the bebopping astringency of his mature work, but there's real muscle in his iced blue waters.

Mid-20th Century art grips down and wakens in Seattle, seen here in the work of Michael Spafford, Robert C. Jones, Fay Jones, Alden Mason and William Ivey.

When Chuck Close met Willem de Kooning, Close told him it was nice to meet a man who'd painted more de Koonings than he had. One of those faux-de Kooning's is in this show, from Close's student days in the early 1960s at the University of Washington. (Only in the Northwest does evidence of this early source live on.)

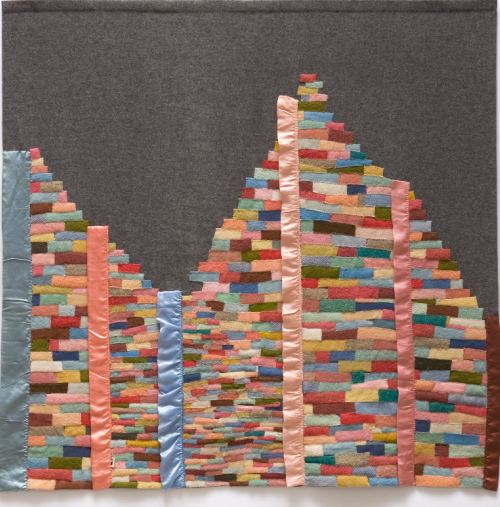

As the exhibit edges towards the present, women begin to make more than an occasional appearance, including Marsha Burns, Alice Wheeler, Claire Cowie, Marie Watt and Susan Seubert.

Marie Watt, Tear Down This Wall, 2007. Reclaimed wool blankets, satin binding, and thread, 61 x 64 inches

I love Seubert's series, 10 Most Popular

Places to Dump a Body in the Columbia River Gorge, from 1998. The museum owns all ten prints.

I love Seubert's series, 10 Most Popular

Places to Dump a Body in the Columbia River Gorge, from 1998. The museum owns all ten prints. Seubert, Lewis and Clark State Park, gelatin silver print, artists proof from an edition of 10; 16 x 20 inches.

In this telling of the Northwest tale, painters rule, not only in the past but in the present. That dominance represents a selective fiction. All we can ask of fiction is that it be convincing, and this one is, at least for the duration of the show.

In this telling of the Northwest tale, painters rule, not only in the past but in the present. That dominance represents a selective fiction. All we can ask of fiction is that it be convincing, and this one is, at least for the duration of the show.Mark Takamichi Miller, Untitled, 1999. Acrylic on canvas, 72 x 64 inches.

Through May 23.

Through May 23. One point you keep reiterating repeatedly is the $500K in lease revenue Regina. The (more important) public-private debate aside, it's the math I've been interested in. Generally speaking, I see the point, $500K/yr certainly seems better than nothing. However at that rate it sure seems like SC is on the loosing side of negotiating a fair market lease rate. Granted, I'm not a real estate agent, so I'm taking a guess here. But really, that $500K at 44K total sq. ft is about $11.25/sq ft. Being somewhat familiar with commercial lease rates I say the park has some wiggle room to leverage a more competitive rate to really bolster its income. I mean if this IS about earning the public $500K a year as you mention, and the trouble-shooting thought process is to go to the private sector--why not think the way the private sector does and NOT operate far below market value?? Which brings me to the fact that if one spreads the anticipated $20M initial TI investment, (that is cost to build the museum), across the max 20-year lease that's 1M a year JUST to build it. Add to that annual rent and operating costs (not to mention inflation) divided by their projected annual attendance and it seems like a risky solvent venture--let alone a profit buster. (Did they talk to Mr. Allen?) So what if Mr. Wright saved some cash and gifted the park 10M in 20 $500K annual installments and the City figured out how to build the damn green space--and hey here's an idea, a part of it could include a botanical garden, with you guessed it, a Chihuly exhibit. Charge admission to it, it would be a fair trade off.

Alice Wheeler never met a natural thing that couldn't be improved upon by the addition of cheap charm.

Wheeler's inkjet prints are part of Made in the U.S.A. at Greg Kucera, through May 15.

Wheeler's inkjet prints are part of Made in the U.S.A. at Greg Kucera, through May 15.His partial block of shotgun houses from New Orleans' Ninth Ward floats on the wall, the white of the wall serving as the water that carried them away.

As Ben told his younger brother Willy, the woods are burning.

As Ben told his younger brother Willy, the woods are burning. Detail:

Detail: The only other artist who makes such an exuberant overuse of tiny nails is Tony Berlant. Berlant uses his as punctuation. They complete the already completed. Van Der Ende's underscore the futility of literal reproduction. From fragments that have outlived their original use he creates another use entirely. His sculptures float, like spirits. No matter how lumbering their presence, they are almost not there, frozen in the act of erasing themselves.

The only other artist who makes such an exuberant overuse of tiny nails is Tony Berlant. Berlant uses his as punctuation. They complete the already completed. Van Der Ende's underscore the futility of literal reproduction. From fragments that have outlived their original use he creates another use entirely. His sculptures float, like spirits. No matter how lumbering their presence, they are almost not there, frozen in the act of erasing themselves.To May 2 at Ambach & Rice.

London bridges are always falling down, but Johnson gives them a last chance to impersonate the functional. The risks he takes are associated with dance and so are his payoffs, those complete moments on the edge of a fall. There are other artists who reassemble furniture to frame it in a new context, including Roy McMakin and Drew Daly. Compared to their work, Johnson's is rough and tumble, Caliban to their Ariel. The silence his work inspires has an undercurrent of domestic turmoil: a heavy remembrance leavened with wit and ungainly grace.

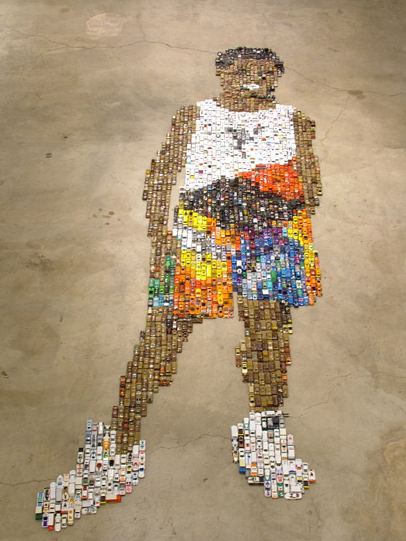

In his mid-twenties, Johnson is mixed race: white mother and black father.

His parents recently lost their home to foreclosure.

He remembers elementary school, feeling pinned in place.

He remembers elementary school, feeling pinned in place. Inside his childhood was a loose and lovely obsessive. Hence his self-portrait (at age 9) in 1,649 hot wheels, each loose on the floor and capable of wheeling away. Some he painted, largely brown, as there aren't a sufficient store of brown hot wheels on the market.

Inside his childhood was a loose and lovely obsessive. Hence his self-portrait (at age 9) in 1,649 hot wheels, each loose on the floor and capable of wheeling away. Some he painted, largely brown, as there aren't a sufficient store of brown hot wheels on the market. Detail:

Detail: At Howard House through May 1. Johnson discusses his work at the gallery on Saturday at noon.

At Howard House through May 1. Johnson discusses his work at the gallery on Saturday at noon.

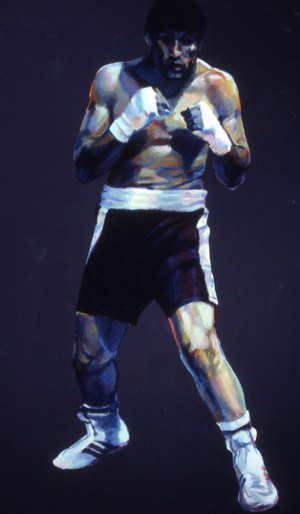

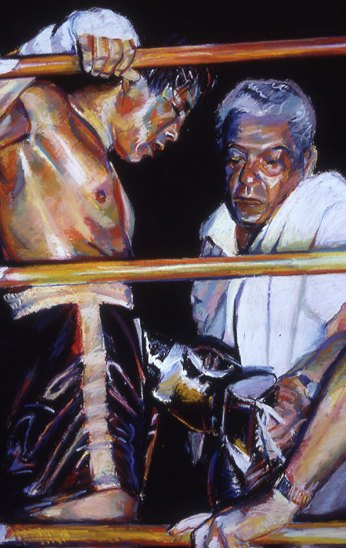

Two Seattle artists who belong in the ring are Laura C. Wright and Randy Hayes.David Hammons' 1989 Champ is impeccable and clever, beautiful and sad. The materials are simple: inner tube, (silver) duct tape, and boxing gloves (with laces hanging down). Hammons smartly mixes a deflated sport with deflated materials to examine the role of the prize fighter in American culture, especially black culture. Before the NBA was a dreamed-of escape-valve for urban youth, boxing offered the bruising, difficult way up. Fighters such as Jack Johnson and Joe Louis were heroes to black America, fighters who crossed-over and had success in mainstream society. But with success came tragedy: Louis died broke, his funeral paid for by German rival Max Schmeling. The tragedy went beyond individual figures: Countless young black men hoped boxing would provide a way up but instead were merely pummeled, used as entertainment or in match-fixing schemes, as disposable cogs in brutal entertainment.

Wright's Momma Said Knock You Out (wool jacket and leather 30 x 24.5 x 5.25 inches 2008) is a tribute to Hammons with a feminist, up-and-at-'em twist.

Hayes began his career in early 1980s, painting figures who deliberately draw the hard light of public scrutiny: strippers, boxers and prostitutes. Light splatters their bodies like oil hitting a hot griddle.

Hayes began his career in early 1980s, painting figures who deliberately draw the hard light of public scrutiny: strippers, boxers and prostitutes. Light splatters their bodies like oil hitting a hot griddle.

As John Yau pointed out in his monograph on Hayes from 2000, titled, Randy Hayes, The World Reveiled, Hayes uses photography to destabilize whatever reality his brush manages to suggest to push his scenes into the unreliable realm of hallucination.

As John Yau pointed out in his monograph on Hayes from 2000, titled, Randy Hayes, The World Reveiled, Hayes uses photography to destabilize whatever reality his brush manages to suggest to push his scenes into the unreliable realm of hallucination.Fallon quotes from Spark's Loitering with Intent from 1981, her character Fleur Talbot, like her a writer:

When people say nothing happens in their lives I believe them. But you must understand that everything happens to an artist; time is always redeemed, nothing is lost and wonders never cease.Because Mallon's full essay is behind a subscribers-only pay wall, here are three more moments from it:

Spark in New York with an office at The New Yorker looks out a window and sees the flashing sign of the Time-Life Building. She told Shirley Hazzard that "When it says 'Time,' I write. When it says 'Life,' I want to go out."

Spark on messages:

I haven't got a message to give to the world, it's the world that gives me messages.And living in Rome, she loved what she called its "immediate touch of antiquity on everyday life." Spark died in 2006.

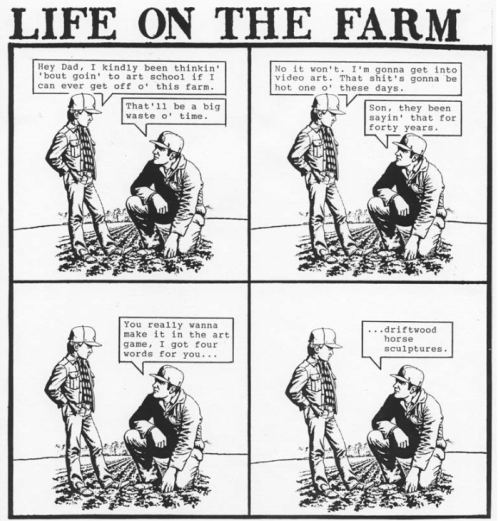

Uh, Dad? That's three words. On the other hand, it isn't every day that a family farmer tips his hat to Deborah Butterfield.

Uh, Dad? That's three words. On the other hand, it isn't every day that a family farmer tips his hat to Deborah Butterfield. Daws' suite of four

Daws' suite of four Reality: The 74-acre Seattle Center is home to a failed, five-acre Fun Forest. Even at its peak, it wasn't that much fun. I was there more times than I want to remember with nephews and nieces, pouring money down the drain of their frustrated desires. Now that the pseudo-fun is gone, what's left is the asphalt on which it rested.

Three of those five acres are going to be open space with a children's garden, a basketball court, a maze for kids to climb through and a big tent for big band dancing, with picnic tables for semi-outdoor dining during the wet season.

What's left is the smaller kiddie ride parcel north of the Monorail and east of the Center House, a little more than one and a half acres. After the carousal and bumper cars are gone, there were no plans and no money to do anything but leave it as an asphalt wasteland until the economy improves.

Enter Jeff Wright of the Howard S. Wright family. He's offering to spend $15 to $20 million to fill it with a temporary museum dedicated to Dale Chihuly. The museum would consist of a green-walled rehab of an existing shed-like arcade building, an open garden and a glass house. Chihuly would fill it with a rotating selection of his work and (potentially) the work of others, bolstered with a wide range of education programs.

Wright's family helped build the Space Needle, and he was chairman of the the Century 21 Comittee that developed a master plan for the next 20 years of development at Seattle Center. He was also a major fundraiser for Seattle Center's McCaw Hall, that houses Seattle Opera.

Wright's family helped build the Space Needle, and he was chairman of the the Century 21 Comittee that developed a master plan for the next 20 years of development at Seattle Center. He was also a major fundraiser for Seattle Center's McCaw Hall, that houses Seattle Opera. Why Chihuly? Because his work is its own kind of fun forest. Full of play and dazzling in its high theatrics, his sculptures give shape to excess and make it shine. They are an international draw, breaking attendance records whenever they are shown.

Then there's the man. Thanks directly to him, Seattle is the Manhattan of glass art. There are now more glass blowers in Seattle than in Venice. Even though Chihuly doesn't know more than a fraction, he's the reason they're here. More than anyone else, he created the environment that makes their careers possible.

Without him, there would be no Pilchuck Glass School and no Museum of Glass. No artist since Robert Rauschenberg has done more to create art opportunities for others. He was the prime mover behind the scenes at the Hilltop Glass program in Tacoma, which gives at-risk youths a chance to put hot air to practical use, a program copied in Seattle at Pratt Fine Arts Center and elsewhere around the country.

He supports more charities than Jimmy Carter. The list of institutions thanking him is nine pages long (single-spaced) and includes museums, art centers, hospitals, schools and health programs, nearly all in this region. Look in vain for this list on his Web site. It isn't there. The master of self-promotion doesn't promote his own good deeds.

Back to the project:

We're talking about less than two acres out of 74 to be the temporary home to this mainstream attraction. Even so, when plans for the Chihuly museum were announced last month, the just-say-no crowd rallied its forces. If the Space Needle were proposed today, rest assured that they would bring it down. Who needs a giant Flash Gordon piece of kitsch? The very idea is an affront to our civic sense of our self-importance.

Contrary to what has been charged, the museum is not a public-space giveaway. It's a lease approved in five-year increments with a 20-year top, with projected revenues to the city running from $300,000 to $500,000 annually.

Who's against Chihuly at the Needle?

1. City Council member Sally Bagshaw, who wants Seattle Center to be Seattle Central Park. (Never was, never will be.) Bagshaw appears to be following David Brewster's musty, myopic lead. He wants a park. Yes to grass, and only if that grass doesn't have any colored glass spears and orbs nestled in its shoots. She says she doesn't want a Seattle Center facility to be a tribute to one man. (Is she planning to raze the Bagley Wright?)

2. Jen Graves, leading an anti-Dale campaign in the Stranger, here.

3. City Council member Jean Godden, who'd like to see a Chihuly museum in Pioneer Square. That's nice Jean, but it's not the proposal, the one that could actually occur in real time on earth. (I have hopes Godden will come to her senses before too much longer.)

4. Random Chihuly haters, venting on various Web sites.

I find the opposition bewildering. They want open space? Open space is not vacant space, and a public attraction is not necessarily a public nuisance. Seattle Center already has 17 acres of rolling greens and plantings. But it also has 30 for profit and nonprofit enterprises, including Pacific Northwest Ballet, Seattle Opera, Intiman Theatre, Bagley Wright Theater, the Children's Theater, the Science Center and EMP.

Robert Nellams, director of Seattle Center, has sensibly requested other proposals for the site. Anybody else with an idea can let him know. There isn't going to be another idea as good as this one, fully-funded with a top draw attraction. If sanity prevails, the museum will become a reality. The major risk is that Wright and Chihuly become discouraged by nay-sayers and withdraw. Neither has to do this project. If they feel they're surrounded by boos, they won't.

About

Blogroll

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

innovations and impediments in not-for-profit arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

Joe Horowitz on music

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary

Recent Comments