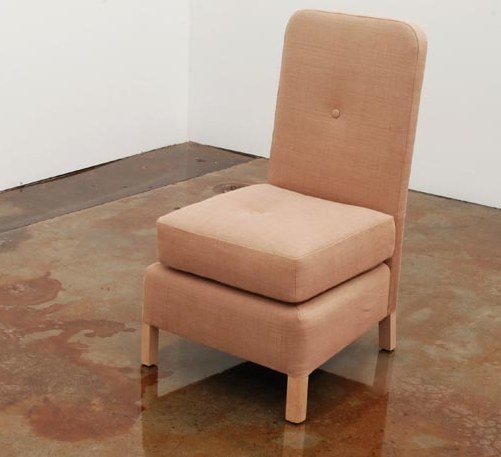

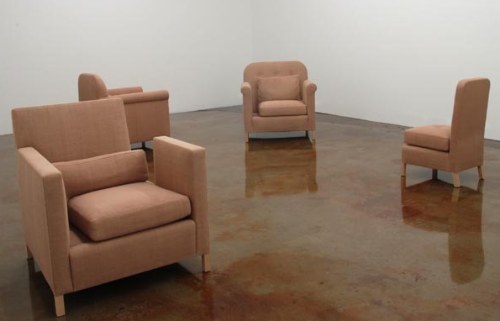

If Joesph Beuys is right that anything can be art and John Cage is right that anything can music, then Roy McMakin‘s furniture makes perfect sense. His chairs, tables, chests and stools both deliver and undermine the idea of utilitarian subservience. Within the fine craftsmanship of their construction is a subversive insistence on a right to be wrong.

Currently at Ambach & Rice is McMakin’s Five Chairs and Ten Tables, a sweet little show with a large contemplative back beat.

Currently at Ambach & Rice is McMakin’s Five Chairs and Ten Tables, a sweet little show with a large contemplative back beat.

Remember Alice’s uncertain relationship to an occasional table? That table was what McMakin’s rarely are – an innocent bystander.

John Baldessari, whose home is full of McMakin’s, described McMakin’s endeavor in an essay included in Roy McMakin: When is a chair not a chair?

John Baldessari, whose home is full of McMakin’s, described McMakin’s endeavor in an essay included in Roy McMakin: When is a chair not a chair?

A love of minimalism (while slightly poking fun at it), a

Mattisean love of color, a goal of keeping others off balance, and a

love of removal/absence, a quest for the paradox of simplicity and

complexity. But overall, a mission to sharpen perception, it’s a

significant accomplishment to get one to really see and understand a

chair (and not feel self-conscious in sitting on it). I don’t think Roy

has designed an ironing board yet, but I’m sure it would double as a

painting.

Michael Darling called him a “master craftsman with the heart of a conceptualist.” His tables and chairs are facts with a twist of dry wit, as in the table top that doesn’t quite fit its base.

In 1965, conceptual artist Joseph Kosuth created One and Three Chairs (a photo of a chair, a chair and a dictionary description of a chair). A point of view that is austerely tough-minded in Kosuth is sweet, almost goofy in McMakin. Kosuth invites us to consider a rigorous idea by turning it over in our minds. McMakin insists on taking the body along for the ride. His work is a voluptous challenge, a reminder that, as long as we’re awake, we might as well be aware, and take no chair for granted.

In 1965, conceptual artist Joseph Kosuth created One and Three Chairs (a photo of a chair, a chair and a dictionary description of a chair). A point of view that is austerely tough-minded in Kosuth is sweet, almost goofy in McMakin. Kosuth invites us to consider a rigorous idea by turning it over in our minds. McMakin insists on taking the body along for the ride. His work is a voluptous challenge, a reminder that, as long as we’re awake, we might as well be aware, and take no chair for granted.

Through Dec. 5.

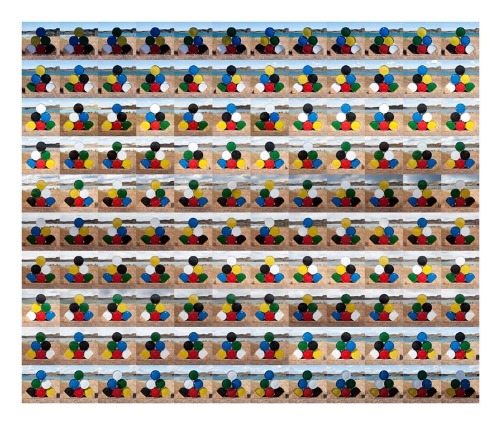

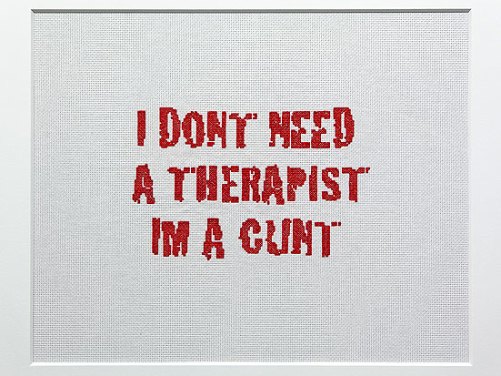

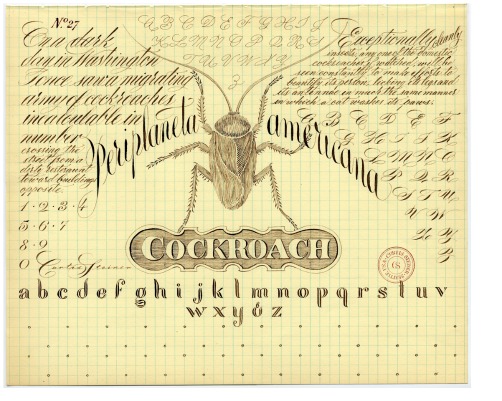

Looks like broccoli to me, which reminds me of E.B. White’s tagline for a 1928 New Yorker cartoon drawn by Carl Rose (Image

Looks like broccoli to me, which reminds me of E.B. White’s tagline for a 1928 New Yorker cartoon drawn by Carl Rose (Image  On Thanksgiving in Seattle, a pipe froze at my house and burst, just in time for a house guest, who’s arriving from Portland in an hour or so. Fortunately, we are eating elsewhere, and there are buckets of snow in the bathroom for that homey historic touch. As Strauss wrote in her email:

On Thanksgiving in Seattle, a pipe froze at my house and burst, just in time for a house guest, who’s arriving from Portland in an hour or so. Fortunately, we are eating elsewhere, and there are buckets of snow in the bathroom for that homey historic touch. As Strauss wrote in her email: Titled Dust to Dust, the exhibit at

Titled Dust to Dust, the exhibit at  Abandoned Crates needs no back story. Into a verdant harmony, what is made by humans floats on a lake. The photo is an immaculate version of the messy masterpiece,

Abandoned Crates needs no back story. Into a verdant harmony, what is made by humans floats on a lake. The photo is an immaculate version of the messy masterpiece, Through Dec. 24.

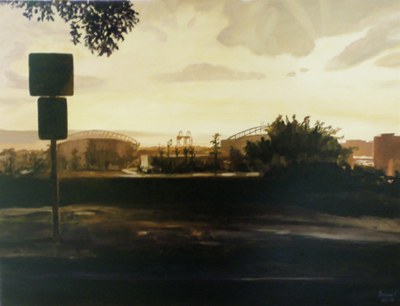

Through Dec. 24. From Columbia City, 2010

From Columbia City, 2010

Peonies I, 2010

Peonies I, 2010

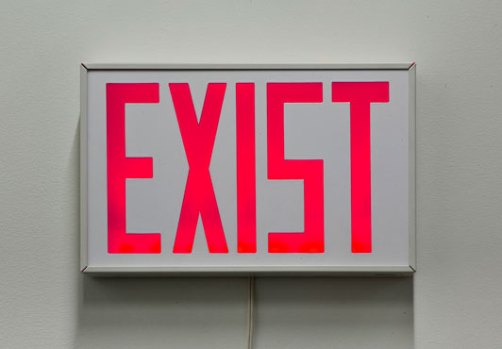

EXIST 2009 Powder coated aluminum w/ LED lights (altered Exit sign)

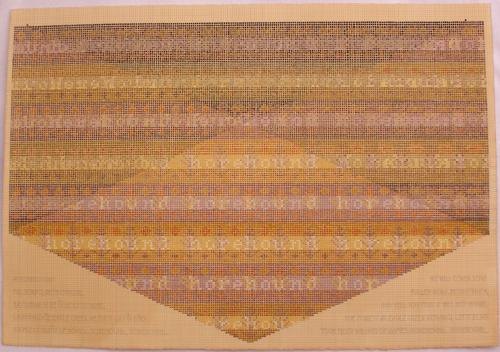

EXIST 2009 Powder coated aluminum w/ LED lights (altered Exit sign) Master of the laid-back she may be, but work takes work. When she wants to relax from the heavy cogitation and technical issues of doing it, she fastens a magnifying lens to her eye and hunches over a table, making interior blizzards full of press type.

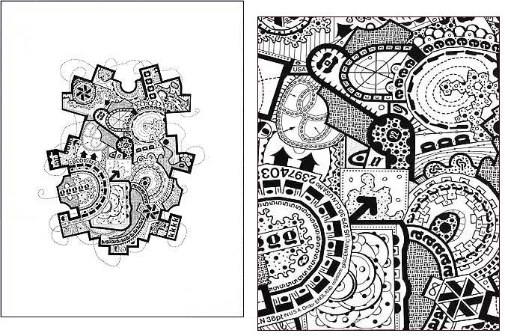

Master of the laid-back she may be, but work takes work. When she wants to relax from the heavy cogitation and technical issues of doing it, she fastens a magnifying lens to her eye and hunches over a table, making interior blizzards full of press type.

Each

Each We

We