Archives for August 2010

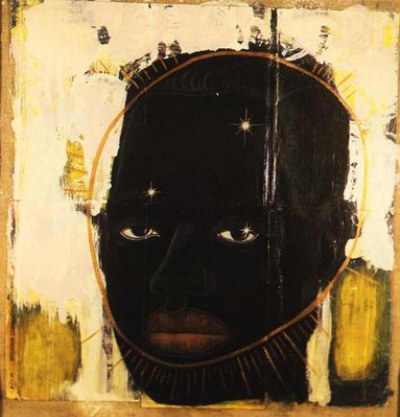

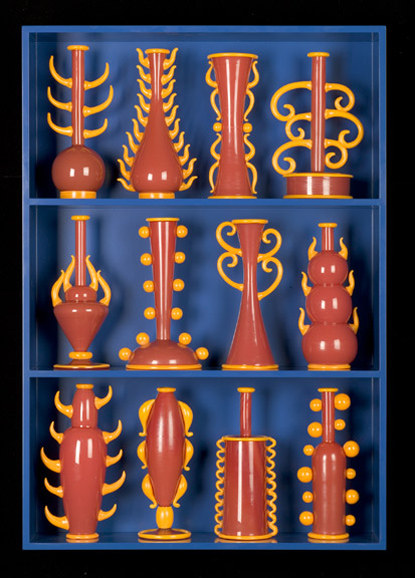

Dante Marioni – the purity of Pop

Spilled milk with a touch of the street:

Dante Marioni‘s vessels are a high class version of high jinks. He favors bright primaries and a mosaic grid of monochromatic patterning so fluid it seems to be circling the drain, ready to dissolve. He likes hourglass curves, delicate feet, swans’ necks and flattened bubbles in towering stacks.

His work has rhythm, grace and attitude.

Son of glass artist Paul Marioni, Dante grew up with glass, taking his first rod out of the furnace at age 10 and saturating himself in his teens in the practice, history and aesthetic possibilities of the medium.

Son of glass artist Paul Marioni, Dante grew up with glass, taking his first rod out of the furnace at age 10 and saturating himself in his teens in the practice, history and aesthetic possibilities of the medium.

By high school, he was a pro and saw no need to interrupt his career with college.

Raised among those who prized art over craft, he found his identity in the craft camp. What moved him was skill and polish. Growing up in Seattle in the 1970s, he was in a good position to acquire both.

In 1971, Dale Chihuly helped found Pilchuck Glass School and hired Venetian master craftsmen to teach there. Following the lead of Venetians such as Lino Tagliapietra and Venice-trained Americans such as Ben Moore and Richard Marquis, Marioni became so skilled that he was in demand on top glass-blowing teams while still in high school. In 1987, at age 23, he had his first solo show at the William Traver Gallery and sold it out. (Those were the days.)

In spite of his insistence that he’s a craftsman first and foremost, there was never been any doubt that he’s an artist. The objects he makes are a response to the world in which he lives. They are his blend of ancient pottery, Art Deco, comics and above all a Pop sensibility, fused and purified by his natural inclination toward the crisp, witty and lean.

His straight-shot tones are cunningly uncomplicated, both direct and silky. His mosaic patterns have an airy, smoky quality. The colors that define them look as if electric currents left them burnt and fragile at their roots.

Every year, working within a well-defined vocabulary, he gets better and better. Sunday is the last day for his latest at Traver Gallery.

Every year, working within a well-defined vocabulary, he gets better and better. Sunday is the last day for his latest at Traver Gallery.

Kurt Cobain – last days

Kurt at the Seattle Art Museum closes Sept. 6.

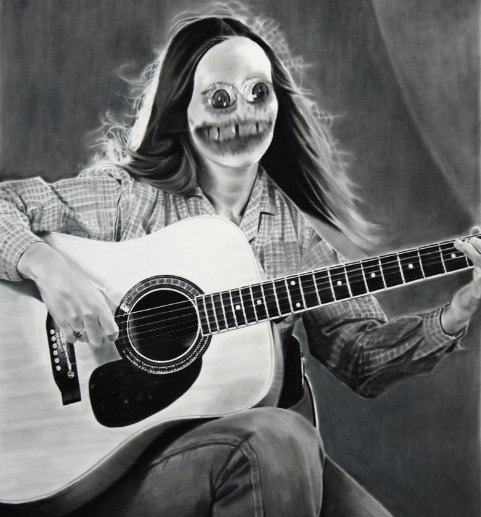

Eric Yahnker isn’t in it but could have been. The freak note would have been welcome.

This too. Nothing like a Jackson Family-Cobain mash up.

This too. Nothing like a Jackson Family-Cobain mash up.

Kurt could have featured YouTube tributes in a corrdior, any corridor. My personal favorite, also, of course, not in the show, is from the Ukulele Orchestra of Great Britain. Smells Like Teen Spirit traveled many miles to get there.

Wanting more doesn’t suggest a lack of respect for curator Michael Darling’s excellent product. I love this show. My review in Modern Painters. Last in, Ben Davis on ArtNet here. Davis does a fine job. Only one paragraph stopped me:

Inasmuch as there is another possibility for relating to pop culture in this show, it comes in the form of Charles Peterson’s black-and-white images of the early Nirvana onstage. Yet as stirring as these pics are, they feel like documentary, not art.

Ben: The is-documentary-photography-art question was resolved before you were born. Anyone who can look at Peterson’s version of Nirvana and question whether it’s art has a hole-in-soul. There’s death all over it, death and love.

Davis is right on about Alice Wheeler, however.

Davis is right on about Alice Wheeler, however.

However, at least one piece at SAM does offer the sought-after spark of connection with Kurt Cobain, in spirit as well as in subject matter: Northwest photographer Alice Wheeler’s image of a young man, with bleached, Cobain-esque hair, and the whisper of a beard, staring out at us with an indecipherable intensity. He wears a Nirvana T-shirt, beneath a red-checked lumberjack shirt. The old Seattle Kingdome sits in the background (long since demolished to make way for not one, but two wasteful replacement stadiums, with corporate names), time-stamping the picture. He stands in front of one of Seattle’s tent cities for the homeless, which, you guess, he calls home. People used to knock grunge as “homeless chic.” Here things flow the other way.

Tent City, Seattle, WA, April, 1999, as the piece is called, touches on the relationship of art, celebrity and the real world, like all the other art here, but the stakes are vivid and clear. Wheeler’s photo hurts a little to look at, because you have the sense of something frail and confused and human looking back at you. But let’s be honest: Only something that hurts a little can be true to the past that this show tries to tap into, or, for that matter, to our present.

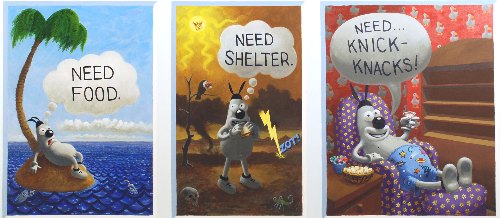

Stuff: the drive to acquire

Marita Dingus – relics of the African diaspora

Like the quilters from Gee’s Bend, Marita Dingus uses what she has, in her case, rags, pop tops, pull tabs, computer innards, film negatives,

Like the quilters from Gee’s Bend, Marita Dingus uses what she has, in her case, rags, pop tops, pull tabs, computer innards, film negatives,

bottles, shells, stones, eye glass lenses, yarn, telephone wire, crime

scene tape, drains, battered baking tins, light-bulb sockets, paper clips, plastic flowers, paint brushes, bits of wire, bent silverware, pacifiers, colored tape, paint and coarse thread.

And glass. Her glass heads (thick, flat and transparent) and bodies (pearish) were created in the hot shop at the Museum of Glass under her direction. Her work has a burrowing mole feeling, as if she’s digging

ever deeper into the earth. Glass gives her burrowing intensity a point

of light, a contrast that functions as an intensifier.

She paints features on them and embeds in each aspects of a different

personality.

Currently at the Francine Seders Gallery are a series of her baskets and babies, both haunted by the idea of family.

Another family-obsessed Seattle artist, Richard Hugo, took Theodore Roethke‘s poetry class at the University of Washington in the late 1940s and puzzled over a final exam question, “What should the modern poet do about his ancestors?”

Another family-obsessed Seattle artist, Richard Hugo, took Theodore Roethke‘s poetry class at the University of Washington in the late 1940s and puzzled over a final exam question, “What should the modern poet do about his ancestors?”

According to Straw for the Fire: Notebooks of Theodore Roethke, 1943-63, (edited by David Wagoner, 1972), Hugo raised his hand. “Do you mean his blood ancestors or the poets who preceded him?”

Roethke gave nothing away. “Just answer the question,” he said.

Hugo, like Dingus, turned the answer into a life’s work.

For Dingus, the ancestral pull is the African diaspora, the trauma of slavery and its cultural reverberations. From her mother and grandmother, she learned to use a sewing machine as someone else might use a pencil, to articulate form and inflect it with personality. Her baskets are a kind of quilt you can hold in your arms.They evoke the rough grace of a garden with its dirt and worms and catch the visual pulse of an erratic pattern.

Ragged grace is her signature. What she can pick up for free she cuts, sews, paints and tapes into her sculptures.

Ragged grace is her signature. What she can pick up for free she cuts, sews, paints and tapes into her sculptures.

In everything she does, there is always the wound and the struggle to survive it. What Roethke wrote about cut flowers applies to her work:

This urge, wrestle, resurrection of dry sticks,

Cut stems struggling to put down feet,

What saint strained so much,

Rose on such lopped limbs to new life?

Through Sept. 5.

Through Sept. 5.

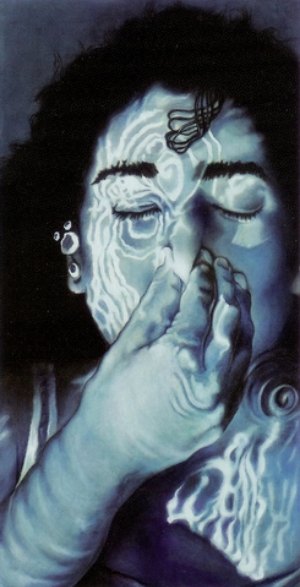

Juan Alonso – between ironwork and smoke

Juan Alonso is interested in the decorative flourishes of old Havana. In his paintings they are smoke – vaporous trails edging toward extinction. Flourishes are for him a family affair. His father was an iron worker from a family of iron workers, responsible for the designs of windows and gates. His mother painted flowers on pots.

Alonso was born in Havana in 1956, three years before Fidel Castro came to power. Alonso remembers food being scarce and people being taken away at night for speaking with less than revolutionary fervor. When he was six, his mother died, and when he was 9, his father sent him to Miami to live with relatives.

Alonso was born in Havana in 1956, three years before Fidel Castro came to power. Alonso remembers food being scarce and people being taken away at night for speaking with less than revolutionary fervor. When he was six, his mother died, and when he was 9, his father sent him to Miami to live with relatives.

His career charts a quiet persistence, an insistence that he will one day produce something of consequence. He was 40 before he found his mature style, a breakthrough that Jacob Lawrence might have been the first to notice. In 1997, when ARTnews asked Lawrence to recommend a young artist who was worthy of greater attention, he wrote back:

The person who comes to mind is Juan Alonso, a Cuban-born painter. His work is deeply personal, autobiographical,

figurative but not illustrative, and it could only be produced by

someone from the Caribbean.

Alonso works in layers of matte and shine in ink, graphite and varnish, building a structure that gives the moist atmospherics around it a ground to engage.

Snakes and chevrons, horizon lines repeatedly breaking over a mountain: These things he suspends in the cloudy mixtures of memory.

Snakes and chevrons, horizon lines repeatedly breaking over a mountain: These things he suspends in the cloudy mixtures of memory.

Alonso has not yet returned to Cuba, and is ambivalent about friends to visit and come home full of praise.

Alonso:

I don’t think they realize that Cubans working in the

tourist hotels are not allowed to eat there or even talk freely to the

customers. I have a nephew in that position. It’s real. But Americans

visit and say the place is lovely. I say, yes, my island is lovely. It’s

a lovely police state.

At Francine Seders through Sept. 5.

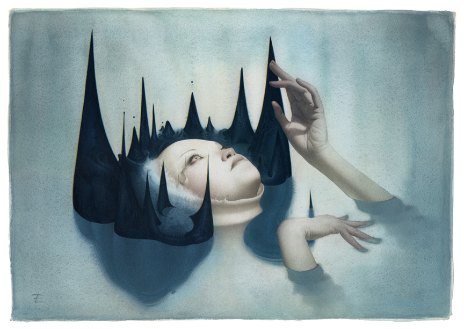

Ophelia – 6 alternatives to drowning

She could have…

1. Held her breath.

2. Shed her heavy clothes and swum to shore.

2. Shed her heavy clothes and swum to shore.

3. Kept her clothes on, relying on youth and excellent muscle tone to pull through.

3. Kept her clothes on, relying on youth and excellent muscle tone to pull through.

4. Let her grievances keep her afloat.

4. Let her grievances keep her afloat.

Eric Fortune 5. Sought Revenge

5. Sought Revenge

6. Remembered that, as Tom Robbins likes to say, it’s never too late to have a happy childhood.

6. Remembered that, as Tom Robbins likes to say, it’s never too late to have a happy childhood.

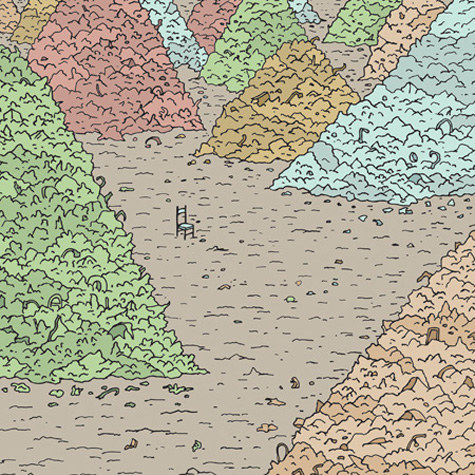

Zack Bent: into the woods

Zack Bent‘s family is his instrument, and his activities with them an arena in which he acts. Unlike others who have made their families their muse, Bent proceeds as if he’s walking a grid to collect trace evidence.

The process is the product: both forlorn and fugitive, like shoveled smoke.

The process is the product: both forlorn and fugitive, like shoveled smoke.

At Vermillion through Sept. 4.

At Vermillion through Sept. 4.

How to spot a lesbian

Claire Johnson recently wondered aloud: “What’s the deal with all of the fake lesbians in erotic art?” Except in the Bible Belt and Afghanistan, gay has a cache no longer available to the straight, not that it’s easy to tell the two apart. Those addicted to visual cues are frequently wrong.

Molly Norris, Self-Portrait, 1982

A character in Sarah Schulman’s 1988 mystery novel, After Delores, felt confident she had cracked the code.

A character in Sarah Schulman’s 1988 mystery novel, After Delores, felt confident she had cracked the code.

Where are we going?

Charlotte’s place. I have the key.

How did you know it was okay to come out to me so quickly? I asked.

Easy. Charlotte taught me the trick. She says that if you’re talking to a woman and she looks you in the eye and really sees you and listens to what you have to say, then you know she’s gay.

As a straight woman, I hope it isn’t true, but I fear it’s a more reliable guide than slicked-back short hair and a man’s shirt.

Lynne Yamamoto – personally anonymous

Because memories are fragile and easily distorted, Lynne Yamamoto casts hers as solids, in marble, slip ceramic and thick black thread. She grew up in Hawaii with no artists in her family save for a grandfather, who wouldn’t have called himself one. In his shed in his spare time, he carved dolls that carried his understanding of his cultural heritage.

What Do-Ho Suh floats, Yamamoto makes as heavy as a tomb.

Currently at Greg Kucera: GRANDFATHER’S SHED, 2008-10

Lāna’i City, Island of Lāna’i

Digitally carved and hand finished marble

Hawaii is a symbol of an easy life, with fish crowding the seas and fruits ripe for the plucking, and yet, following World War II, canned goods became a staple, particularly (and inexplicably) Spam. Yamamoto’s rendering in vitreous china gives the cans the purity of Communion wafers.

Hawaii is a symbol of an easy life, with fish crowding the seas and fruits ripe for the plucking, and yet, following World War II, canned goods became a staple, particularly (and inexplicably) Spam. Yamamoto’s rendering in vitreous china gives the cans the purity of Communion wafers.

PROVISIONS, POST-WAR, Pacific Asia and U.S. (Sardine), 2007-10

Vitreous china

PROVISIONS, POST-WAR, Pacific Asia and U.S. (Spam), 2007-10

PROVISIONS, POST-WAR, Pacific Asia and U.S. (Spam), 2007-10

Vitreous china

Just as human immigrants came to the island in waves, displacing the first peoples, insects immigrated with them, pushing the original occupants out of their niches. Yamamoto’s work is so beautifully crafted and physically recessive, it hides as much as it reveals. The exception is her embroidery on found doilies, which she displays from the back side, with black knots providing the relish of a coarse vitality: Dollies undone.

Just as human immigrants came to the island in waves, displacing the first peoples, insects immigrated with them, pushing the original occupants out of their niches. Yamamoto’s work is so beautifully crafted and physically recessive, it hides as much as it reveals. The exception is her embroidery on found doilies, which she displays from the back side, with black knots providing the relish of a coarse vitality: Dollies undone.

INSECT IMMIGRANTS, AFTER ZIMMERMAN (1948), 2009-10

Embroidery on found doilies

Camamponotus maculates (carpenter ant)

Camamponotus maculates (carpenter ant)

Through Oct. 2.

Through Oct. 2.