Darren Waterston, Five Oblivions 3 (peak), oil on oval wood panel, 12 x 16 inches, at Greg Kucera Gallery

Anybody want to add one?

Regina Hackett takes her Art to Go

Darren Waterston, Five Oblivions 3 (peak), oil on oval wood panel, 12 x 16 inches, at Greg Kucera Gallery

Anybody want to add one?

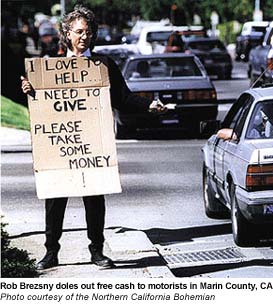

While not an expert in seeking remuneration, I instinctively feel that begging is not the best strategy for arts writers.

Culture Grrl disagrees here, here, here and most recently here, the last having the distinction of being not only plaintive (“Did no one miss me while I was gone?”) but threatening ( “See you tomorrow (maybe).”)

Culture Grrl (Lee Rosenbaum) is an industrious reporter, especially on museum administration news. But if she’s that intent on raising a bit of what Bernie Bertie Wooster calls the necessary, she should consult an expert.

Or hook up with Rob Brezsny. Their needs appear to be in sync.

(Click images to enlarge.)

The hill and dale of Thomas Hart Benton, detail from Susanna and the Elders, the de Young Museum in S.F. (Photo, C-Monster.)

Benton swings again: John Currin, The Gimp (Gagosian Gallery)

(Click on images to see them larger)

(Click on images to see them larger)

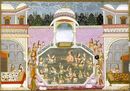

History does not misplace a movement that rewrites the rules of its region across a time span of two centuries, but few of the 58 paintings in Garden and Cosmos: The Royal Paintings of Jodhpur have ever been seen in the wider world, even by scholars.

Their base is the miniature. Jodhpur painters could produce palm-size cosmologies full of gods and goddesses, kings and queens, dancing girls, flute players, warrior monkeys and battles waged on the backs of elephants.

Over time, however, they allowed themselves more room. And instead of filling bigger spaces in a miniaturist style, they expanded into wider worlds with open, rolling rhythms and colors with air in them. The jewel-box shine of the miniature became the saffron and sherbet shades of a dynamic pleasure dome.

However gorgeous, and it is gorgeous, such a show wouldn’t be expected to attract big numbers in Seattle, even with ecstatic local reviews (here, here, here and here). My favorite review headline from this group (first click) comes from Jen Graves – Your Brain Lights Up With Happiness.

However gorgeous, and it is gorgeous, such a show wouldn’t be expected to attract big numbers in Seattle, even with ecstatic local reviews (here, here, here and here). My favorite review headline from this group (first click) comes from Jen Graves – Your Brain Lights Up With Happiness.

Yes it does. Maybe outrageous skill and blissed-out iconography are more powerful attractions than previously imagined, or maybe it’s the Slumdog effect – all things Indian riding the Slumdog wave.

Whatever the reason, SAM reports that Garden and Cosmos is running 200 percent over the museum’s optimistic pre-crash projections. It’s on view at the museum’s sleepy satellite venue, the Seattle Asian Art Museum in Volunteer Park. Its numbers are dwarfed only by King Tut in 1978 and Bruce Guenther’s Jacob Lawrence retrospective in 1986, both before SAM moved its headquarters downtown.

Speaking of downtown, SAM’s doing well there too. Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness is attracting the pre-crash projection of 20,000 visitors in the first three weeks. Considering the attendance dive SAM experienced after the economy fell apart in the last year of the Bush administration, that number is amazing.

Possibly it has something to do with this. Advertising its pay-what-you-can admission policy (instead of keeping it a secret), was second on this list of what SAM needs to do to connect with a younger audience. So far, so good.

(Click on images to see them larger.)

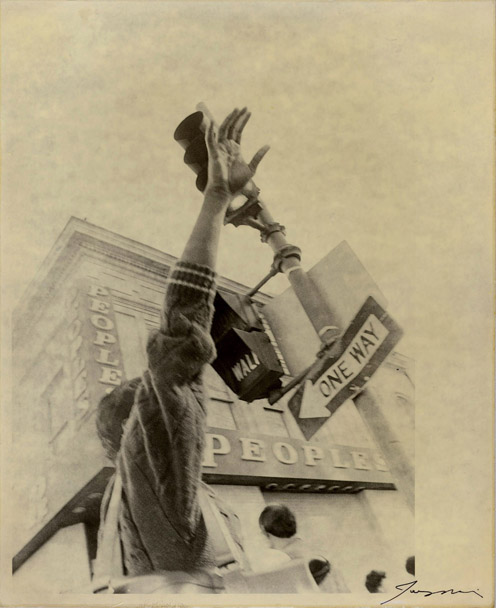

Helen Levitt died in her sleep on Sunday. She was 95. Lovely Margarett Loke obit in the New York Times here.

Helen Levitt died in her sleep on Sunday. She was 95. Lovely Margarett Loke obit in the New York Times here.

For someone who had a long and distinguished career, Levitt seldom had much to say about it. If she grew tired of having critics exclaim over her early work and ignore her later, she rarely expressed this view in public.

In the late 1930s and 1940s, she captured the animal radiance of an urban childhood – the chaotic fun of hanging out where lots was happening. As far as we know now, which isn’t enough, she didn’t work much in the 1950s and 1960s but came back big in the 1970s.

In the late 1930s and 1940s, she captured the animal radiance of an urban childhood – the chaotic fun of hanging out where lots was happening. As far as we know now, which isn’t enough, she didn’t work much in the 1950s and 1960s but came back big in the 1970s.

Her career charts a course from the specific to the nearly abstract, from black-and-white to color. In later years, she liked to lift the edges off objects and give them a shake.

I remember a print of a woman dressed neatly in a grid of crisscrossing checks leaning into a cab. The car’s checkered trim seems to have wondered off her skirt. In another, three motley roosters stroll down a street, heading for a clump of cheap chairs with gold and red floral patterns blooming with startling force under plastic wrap.

Her unifying thread is a focus on gestures. Like Henri Cartier-Bresson and Weegee, she specialized in the fleeting, spontaneous and tossed off.

In her early work, children rule. They are ruffians with the grace of angels. In what is probably her most famous image, three of them stand staggered on the steps of a brownstone, two in face masks, the third struggling to tie hers on.

In her early work, children rule. They are ruffians with the grace of angels. In what is probably her most famous image, three of them stand staggered on the steps of a brownstone, two in face masks, the third struggling to tie hers on.

Ralph Eugene Meatyard hit the same theme, but his kids are grotesques. Hers is tender. He put the masks on the children and posed them. She found them as they moved outdoors and caught them in the act of being themselves.

In Seattle, Levitt’s work is at the G. Gibson Gallery.

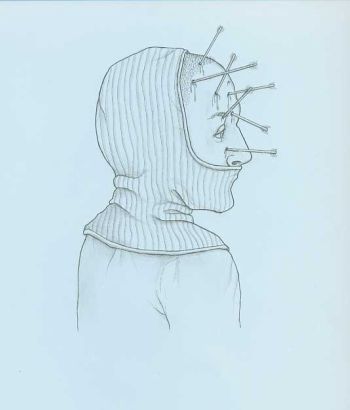

St. Sebastian is an S&M icon in Roman Catholic iconography. Joe Biel removes the weapon from its signal place in erotica and locates it in the horror of the day-to-day – an image of someone who is dead and doesn’t know it.

From Carol Diehl’s Art Vent, Daniel G. Amen’s idea that a

pathological aversion to paperwork could indicate an imbalance in the prefrontal cortex. Amen’s prescription? Hire someone else to do it.

In other words, those with a paralyzing reluctance to fill out anything resembling a form are not just self-indulgent procrastinators but victims of their chemicals. Reading this, I was awash in my own Cherry Orchard moment, a feeling that, in the future, advances in medicine will make it possible for the formerly slothful to be tidy and timely. No more drifts of unopened mail obscuring the work space on their desks.

Chekhov’s characters believed in the future. They believed that in time the ability to work would make everyone free, when the truth of future was Stalin. It’s the single greatest example of history deepening the meaning of art, instead of the reverse.

TROFIMOV. The human race progresses, perfecting its powers. Everything that is unattainable now will some day be near at hand and comprehensible, but we must work, we must help with all our strength those who seek to know what fate will bring. Meanwhile in Russia only a very few of us work. The vast majority of those intellectuals whom I know seek for nothing, do nothing, and are at present incapable of hard work.

And Trofimov, again:

Believe me, Anya, believe me! I’m not thirty yet, I’m young, I’m still a student, but I have undergone a great deal! I’m as hungry as the winter, I’m ill, I’m shaken. I’m as poor as a beggar, and where haven’t I been–fate has tossed me everywhere! But my soul is always my own; every minute of the day and the night it is filled with unspeakable presentiments. I know that happiness is coming, Anya, I see it already. . .

ANYA. [Thoughtful] The moon is rising.EPIKHODOV is heard playing the same sad song on his guitar. The moon rises. Somewhere by the poplars VARYA is looking for ANYA and calling, “Anya, where are you?”

TROFIMOV. Yes, the moon has risen. [Pause] There is happiness, there it comes; it comes nearer and nearer; I hear its steps already. And if we do not see it we shall not know it, but what does that matter? Others will see it!

In what must be one of the least satisfying copyright suits ever filed by a major artist, Dale Chihuly resolved his 14-month-long copyright dispute with glass entrepreneur Robert Kaindl more than two years ago. Earlier than that, glass art’s main man settled a similar suit with glass blower Bryan Rubino, who had worked for Chihuly for nearly a decade.

Both Rubino and Kaindl had counter sued. Suddenly, all suits were void, and terms of the settlements sealed. At the time, Chihuly said if it had it to do over, he wouldn’t.

To sue or not to sue. That is the question. I’m not the kind of person who wants to sue somebody, and yet I did. I got kind of fed up.

What was he fed up with?

I recently saw an ad for Kaindl in a luxury goods magazine. Here’s a piece from his Web site, followed by one from Chihuly’s. (Click on images to make them bigger.)

That’s not all. When Chihuly Inc. announced its suit, press coverage

That’s not all. When Chihuly Inc. announced its suit, press coverage

tended to be sympathetic to the defendants (underdogs) rather than the

plantiff (top dog).

The worst offender was the Seattle Times. After six months of digging, the paper produced a bloated and inconsequential three-part Chihuly series.

It suggested grave wrongs were being uncovered at Chihuly Inc., maybe just over the hill of the next paragraph.

As written by investigative reporter Susan Kelleher and art critic Sheila Farr, there was nothing but smoke over that hill. My favorite headline in the tell-all wannabe series was “Chihuly Benefits from his own Philanthropy.” Who doesn’t?

As written by investigative reporter Susan Kelleher and art critic Sheila Farr, there was nothing but smoke over that hill. My favorite headline in the tell-all wannabe series was “Chihuly Benefits from his own Philanthropy.” Who doesn’t?

Here’s how the ST framed the idea of the suit:

Headline: Chihuly turns up heat on competing artists.

Subhead: He’s been guarding his artistic style for years, warning others not to copy shapes and techniques he claims as his. But some say he’s gone too far with a copyright lawsuit.

That’s fair and balanced. Welcome to Seattle’s version of the no-spin zone.

My Chihuly profile here.

Fashion designers are more or less resigned to knockoffs, but artists aren’t. After Jeff Koons floated a basketball in a half-filled fish tank and called it a sculpture in the early 1980s, nobody rushed to market with the same idea. But Chihuly straddles two worlds, both art and craft. Like fashion, craft gets copied. Who hasn’t seen an imitation Tiffany lamp or an imitation Charles Eames’ chair?

What got lost in all this was art, but what chance does art have when conflict is on the table, along with juicy personal information and the opportunity to scorn a homegrown celebrity? None at all.

Time to move on. Chihuly has. But as I held Kaindl’s ad in my hands, the injustice of the outcome rankled.

Early in the 1990s, Richard Billingham rewrote the rules of the visual memoir, documenting his family with an appalled affection.

Billingham’s disreputable dad Ray has a mirror personality in Scobie from Lawrence Durrell’s The Alexandria Quartet, first book:

Billingham’s disreputable dad Ray has a mirror personality in Scobie from Lawrence Durrell’s The Alexandria Quartet, first book:

Scobie is getting on for seventy and still afraid to die; his one fear is that he will awake one morning and find himself lying dead. Consequently it gives him a severe shock every morning when the water-carriers shriek under his window before dawn, waking him up. For a moment, he says, he dare not open his eyes. Keeping them fast shut (for fear that they might open on a heavenly host or the cherubims hymning) he gropes along the cake-stand beside his bed and grabs his pipe. It is always loaded from the night before and an open matchbox stands beside it. The first whiff of seaman’s plug restores both his composure and his eyesight. He breathes deeply, grateful for the reassurance. He smiles. He gloats. …

He places his wrinkled fingers to his chest and is comforted by the sound of his heart at work, maintaining a tremulous circulation in that venous system whose deficiencies (real or imaginary I do not know) are only offset by brandy in daily and all-but lethal does. He is rather proud of his heart.

Billingham went from shooting pictures of his nearest and dearest to photographing at the zoo, not a large leap. He’s in the current exhibit at Western Bridge.

an ArtsJournal blog