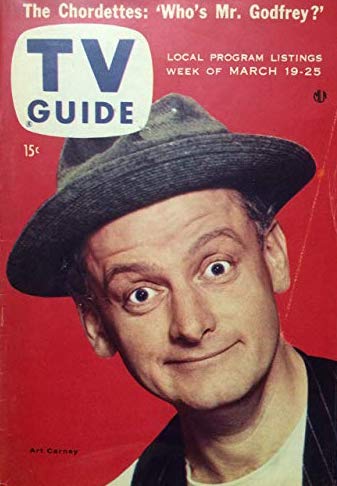

Art Carney, who was born a century ago yesterday, is now mainly remembered for his long tenure as Jackie Gleason’s second banana on The Honeymooners. Needless to say, there are worse fates for an actor than being remembered for just one role, starting with not being remembered at all. But there was much more to Carney than his much-loved impersonation of Ed Norton, the bumbling sewer worker, and the reason why you probably aren’t aware of that fact that is one of the saddest stories I know.

Art Carney, who was born a century ago yesterday, is now mainly remembered for his long tenure as Jackie Gleason’s second banana on The Honeymooners. Needless to say, there are worse fates for an actor than being remembered for just one role, starting with not being remembered at all. But there was much more to Carney than his much-loved impersonation of Ed Norton, the bumbling sewer worker, and the reason why you probably aren’t aware of that fact that is one of the saddest stories I know.

Carney, who started out as a comedian, discovered almost accidentally as a byproduct of the popularity of The Honeymooners that he had the stuff great character actors are made of. He was all over the tube in the long-gone days of live network TV, appearing in delightful small-screen versions of Charley’s Aunt and Harvey and giving a powerfully persuasive performance in “The Velvet Alley,” a Playhouse 90 episode from 1959 written by Rod Serling in which he played a disillusioned TV writer who bore a suspiciously close resemblance to Serling himself. A year later, Serling wrote another, equally memorable role for Carney, who played an alcoholic department-store Santa Claus in a Twilight Zone episode called “The Night of the Meek” that cut far closer to the knuckle than its viewers knew at the time.

Then, in 1965, Carney created the role of Felix Ungar in the original Broadway production of Neil Simon’s The Odd Couple, co-starring with Walter Matthau and receiving reviews that at the very least should have established him as a top-tier stage actor. But Jack Lemmon replaced him in the 1968 film version of The Odd Couple, and that was that: Carney continued to play Ed Norton on TV, and he even contrived to win a Tony in 1968 for his performance in the short-lived Broadway production of Brian Friel’s Lovers, but he’d missed his chance to become a full-fledged star in his own right.

Then, in 1965, Carney created the role of Felix Ungar in the original Broadway production of Neil Simon’s The Odd Couple, co-starring with Walter Matthau and receiving reviews that at the very least should have established him as a top-tier stage actor. But Jack Lemmon replaced him in the 1968 film version of The Odd Couple, and that was that: Carney continued to play Ed Norton on TV, and he even contrived to win a Tony in 1968 for his performance in the short-lived Broadway production of Brian Friel’s Lovers, but he’d missed his chance to become a full-fledged star in his own right.

The problem, as everybody in the business was all too well aware, was that Carney, like the character he played in “The Night of the Meek,” was an alcoholic who also suffered from chronic depression. He’d been able to keep his drinking under control in the Fifties, but he lost his footing early in the run of The Odd Couple, in part because his own marriage, like that of Felix Ungar, was breaking up.

To be sure, Carney—who would always make a point of describing himself as an actor, not a comedian—was by all accounts brilliantly successful in infusing his interpretation of the part with the emotional turmoil of his offstage life. As he later recalled:

There were so many parallels to my own life in that role. The character carries around pictures of his kids and his house and shows them to visitors. During one performance, when I was doing that on stage I broke down and cried.

But nobody in Hollywood was willing to take a chance on casting a drunk who’d never appeared in a film role of any substance, and so Carney was never seriously considered for the part. The brass ring passed him by, and within a few years his career had dried up.

It wasn’t until 1974 that Carney stopped drinking for good, the same year in which he finally landed a leading film role that was worthy of his talents. His richly wrought performance in Paul Mazursky’s Harry and Tonto, in which he played a lonely, irascible widower who is forced to move out of his Upper West Side apartment and start a new life when the building in which he lives is torn down, won him a well-deserved best-actor Oscar and brought him the big-screen success that had previously eluded him. Three years later he played an over-the-hill private detective in Robert Benton’s The Late Show, a neo-noir comedy-drama in which he once again showed what he could do with a meaty part. He acted as often as he cared to for the rest of his life, and while he would never again stretch himself, his supporting roles in such comedies as House Calls and W.W. and the Dixie Dancekings were always carried off with the grumpy charm that became his trademark.

It wasn’t until 1974 that Carney stopped drinking for good, the same year in which he finally landed a leading film role that was worthy of his talents. His richly wrought performance in Paul Mazursky’s Harry and Tonto, in which he played a lonely, irascible widower who is forced to move out of his Upper West Side apartment and start a new life when the building in which he lives is torn down, won him a well-deserved best-actor Oscar and brought him the big-screen success that had previously eluded him. Three years later he played an over-the-hill private detective in Robert Benton’s The Late Show, a neo-noir comedy-drama in which he once again showed what he could do with a meaty part. He acted as often as he cared to for the rest of his life, and while he would never again stretch himself, his supporting roles in such comedies as House Calls and W.W. and the Dixie Dancekings were always carried off with the grumpy charm that became his trademark.

When Carney died in 2003, the obits all mentioned Ed Norton first and foremost, which was fair enough. To have played an iconic sitcom character had long since earned him a spacious room in the mansion of posterity. But for those who were aware of the other things that he might have done with his great gifts, Carney’s death was the occasion for a different kind of mourning, the kind to which Stephen Sondheim refers in the most poignant song from his greatest musical:

When Carney died in 2003, the obits all mentioned Ed Norton first and foremost, which was fair enough. To have played an iconic sitcom character had long since earned him a spacious room in the mansion of posterity. But for those who were aware of the other things that he might have done with his great gifts, Carney’s death was the occasion for a different kind of mourning, the kind to which Stephen Sondheim refers in the most poignant song from his greatest musical:

You take your road.

The decades fly.

The yearnings fade, the longings die,

You learn to bid them all goodbye.

I hope that Art Carney wasn’t haunted in old age by the road he didn’t take—but I’d be surprised if it didn’t come to his mind on occasion. Few things sting more fiercely than the unbidden memory of wasted time.

* * *

Art Carney’s New York Times obituary is here.

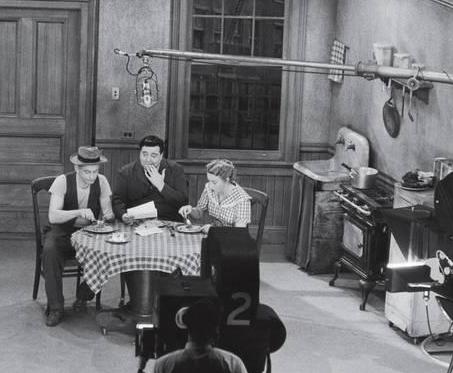

A scene from “The Velvet Alley,” originally telecast live by CBS in 1959 as an episode of Playhouse 90. The script is by Rod Serling and the episode was directed by Franklin J. Schaffner. Jack Klugman plays Carney’s agent:

A scene from “The Night of the Meek,” a 1960 Twilight Zone episode written by Serling and directed by Jack Smight in which Carney plays opposite John Fiedler:

Glenda Jackson presents Carney with his Oscar for Harry and Tonto: