Now that Mrs. T is awaiting a double lung transplant, I’ve cut down on my out-of-town reviewing, and I haven’t flown anywhere since I got back from Houston in March. Up to a point, that’s fine with me: I hate airports, and there are still plenty of worthy companies outside of Manhattan to which I can drive without difficulty. The catch is that I last visited Smalltown, U.S.A., the place where I grew up and where my brother and sister-in-law still live, in 2015, and I’ve been longing to go back. So when the need for further tests delayed Mrs. T’s being listed for transplant in Philadelphia, the two of us talked it over and decided that it would be safe for me to fly out to St. Louis to see the Muny’s revival of Jerome Robbins’ Broadway, about which I wrote last year, then drive down to Smalltown and spend a couple of nights with my family before returning to New York.

Now that Mrs. T is awaiting a double lung transplant, I’ve cut down on my out-of-town reviewing, and I haven’t flown anywhere since I got back from Houston in March. Up to a point, that’s fine with me: I hate airports, and there are still plenty of worthy companies outside of Manhattan to which I can drive without difficulty. The catch is that I last visited Smalltown, U.S.A., the place where I grew up and where my brother and sister-in-law still live, in 2015, and I’ve been longing to go back. So when the need for further tests delayed Mrs. T’s being listed for transplant in Philadelphia, the two of us talked it over and decided that it would be safe for me to fly out to St. Louis to see the Muny’s revival of Jerome Robbins’ Broadway, about which I wrote last year, then drive down to Smalltown and spend a couple of nights with my family before returning to New York.

I hadn’t flown since March, and I didn’t miss it in the slightest, especially when I got to LaGuardia Airport, large tracts of which have been reduced to chaos by the construction of a new terminal, part of a complete renovation that is officially scheduled to be finished in 2026. This being New York, I don’t believe a word of it, nor do I know what possessed me to fly to St. Louis via LaGuardia. All I can tell you is that the place is a mess and that I hope never to see it again.

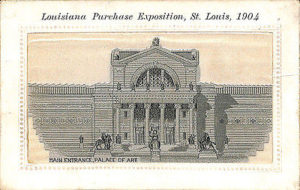

Not wanting to risk missing any part of the show, I landed inconveniently early, picked up a rental car, and drove to Forest Park and the St. Louis Art Museum, there to kill time in the best of all possible ways. The museum is housed in the last surviving building from the Louisiana Purchase Exposition, better known as the 1904 World’s Fair, which musical-comedy buffs will recall from the last scene of Meet Me in St. Louis. As a result, it has a pleasingly old-fashioned air that hasn’t been dispelled by the opening of a new wing that was built in 2013 to house its collection of contemporary art. It’s a place where people go to look at art, not to tell their friends that they’re doing so—I saw only one person reflexively pulling out her smartphone to snap a picture as she walked up to a painting—and the fact that admission to the permanent collection is free of charge strengthens your sense that St. Louisans properly appreciate the presence in their city of such an oasis.

Not wanting to risk missing any part of the show, I landed inconveniently early, picked up a rental car, and drove to Forest Park and the St. Louis Art Museum, there to kill time in the best of all possible ways. The museum is housed in the last surviving building from the Louisiana Purchase Exposition, better known as the 1904 World’s Fair, which musical-comedy buffs will recall from the last scene of Meet Me in St. Louis. As a result, it has a pleasingly old-fashioned air that hasn’t been dispelled by the opening of a new wing that was built in 2013 to house its collection of contemporary art. It’s a place where people go to look at art, not to tell their friends that they’re doing so—I saw only one person reflexively pulling out her smartphone to snap a picture as she walked up to a painting—and the fact that admission to the permanent collection is free of charge strengthens your sense that St. Louisans properly appreciate the presence in their city of such an oasis.

I visited the St. Louis Art Museum for the first time well into adulthood, my parents not being museumgoers. Too bad for me: it is, I suspect, a near-ideal first museum for those who know little of the visual arts, aspiring to encyclopedic status without being too big to swamp the casual visitor. (It houses 34,000 works of art, one-tenth as many as are owned by the Art Institute of Chicago.) Most of the show-stoppers, which include first-class pieces by Holbein, Titian, Monet, Van Gogh, and Matisse, are on more or less continuous display, and you can see them all without becoming art-drunk along the way. Like many regional museums, the museum also makes a point of hanging lesser-known canvases by such unfashionable American masters as Stuart Davis, Arthur Dove, Marsden Hartley, and John Twachtman, which are sprinkled throughout the galleries with gratifying frequency.

I visited the St. Louis Art Museum for the first time well into adulthood, my parents not being museumgoers. Too bad for me: it is, I suspect, a near-ideal first museum for those who know little of the visual arts, aspiring to encyclopedic status without being too big to swamp the casual visitor. (It houses 34,000 works of art, one-tenth as many as are owned by the Art Institute of Chicago.) Most of the show-stoppers, which include first-class pieces by Holbein, Titian, Monet, Van Gogh, and Matisse, are on more or less continuous display, and you can see them all without becoming art-drunk along the way. Like many regional museums, the museum also makes a point of hanging lesser-known canvases by such unfashionable American masters as Stuart Davis, Arthur Dove, Marsden Hartley, and John Twachtman, which are sprinkled throughout the galleries with gratifying frequency.

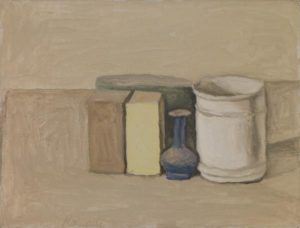

I last visited the St. Louis Art Museum in 2009, so I knew I’d want to spend a couple of hours there, and I also knew which piece I’d see first: Giorgio Morandi’s Still Life, painted in 1953, bought from the artist by a pair of married collectors in 1957, and presented to the museum the same year. Did they not care for it, or was it bought specifically as a gift? I’ve no idea, but I do know that it’s one of Morandi’s loveliest canvases, among the finest examples of his work in this country, and the St. Louis Art Museum, unlike most of the other American museums that own Morandis, keeps it on view. It happens that Mrs. T and I had the great good fortune to acquire a Morandi etching late last year, but I hadn’t seen any of his paintings since then, and as I stood before this one, I felt the mysterious pride that only the collector knows, a sense that I was somehow at one with a man whom I rank among the greatest artists of the twentieth century.

I last visited the St. Louis Art Museum in 2009, so I knew I’d want to spend a couple of hours there, and I also knew which piece I’d see first: Giorgio Morandi’s Still Life, painted in 1953, bought from the artist by a pair of married collectors in 1957, and presented to the museum the same year. Did they not care for it, or was it bought specifically as a gift? I’ve no idea, but I do know that it’s one of Morandi’s loveliest canvases, among the finest examples of his work in this country, and the St. Louis Art Museum, unlike most of the other American museums that own Morandis, keeps it on view. It happens that Mrs. T and I had the great good fortune to acquire a Morandi etching late last year, but I hadn’t seen any of his paintings since then, and as I stood before this one, I felt the mysterious pride that only the collector knows, a sense that I was somehow at one with a man whom I rank among the greatest artists of the twentieth century.

Not having eaten since I’d grabbed an overpriced breakfast sandwich at LaGuardia, I drove straight from the museum to the Hill, St. Louis’ nearby Italian neighborhood and the best place to go for toasted ravioli, the local dish of choice. Having previously sought out culinary counsel on Twitter, I went to Anthonino’s Taverna, a nondescript but comfortable bar and grill where I chowed down on six perfectly toasted ravioli and a Caesar salad, surrounded by nice Midwestern types who were there not to show off but to eat.

Not having eaten since I’d grabbed an overpriced breakfast sandwich at LaGuardia, I drove straight from the museum to the Hill, St. Louis’ nearby Italian neighborhood and the best place to go for toasted ravioli, the local dish of choice. Having previously sought out culinary counsel on Twitter, I went to Anthonino’s Taverna, a nondescript but comfortable bar and grill where I chowed down on six perfectly toasted ravioli and a Caesar salad, surrounded by nice Midwestern types who were there not to show off but to eat.

After dinner I returned to Forest Park, home of the Muny, a century-old eleven-thousand-seat outdoor amphitheatre where Broadway musicals are performed every summer. I wasn’t there to review Jerome Robbins’ Broadway for The Wall Street Journal, though: Laura Jacobs had already done that a couple of days earlier, allowing me to cover an equally important opening in the Berkshires. I came simply to enjoy myself, and to remember the past.

I saw Jerome Robbins’ Broadway six times in 1989, assuming that it was a once-in-a-lifetime event and figuring I’d be a fool not to grab the chance to see Robbins’ greatest musical-comedy production numbers painstakingly restaged by their creator. The experience was so overwhelming that it left a life-changing impression on me: the very first piece I ever wrote about dance, which appeared in the late, lamented New Dance Review, was an essay about “the Robbins show,” as everyone called it back then.

I spent the next nine years covering Robbins’ ballet premieres for the New York Daily News. I actually sat next to him, purely by chance, at the first performance of New York City Ballet’s 1998 revival of Les Noces, his last opening night. Two months later, I wrote his obituary for Time. He bestrode my early years in New York, a creative giant to whom I never spoke—I didn’t have the nerve to introduce myself to him—but who was still as much a part of my life as anyone I knew personally in those far-off days.

For all these reasons, I would never claim to say with any pretense of objectivity how well the Muny performed Jerome Robbins’ Broadway. Closely though I watched the performance, I did so through a scrim of tears, and my head was full of deep-etched memories (though I wasn’t quite so carried away as to fail to notice the mid-show protest that I wrote about a few days later in the Journal). I wasn’t exactly young in 1989, just as I’m not exactly old now, but it’s also true that a lot of water has flowed under the bridge of my life as an aesthete since I first saw the Robbins show. Having never expected to see it again, I’m not surprised that doing so made me cry.

For all these reasons, I would never claim to say with any pretense of objectivity how well the Muny performed Jerome Robbins’ Broadway. Closely though I watched the performance, I did so through a scrim of tears, and my head was full of deep-etched memories (though I wasn’t quite so carried away as to fail to notice the mid-show protest that I wrote about a few days later in the Journal). I wasn’t exactly young in 1989, just as I’m not exactly old now, but it’s also true that a lot of water has flowed under the bridge of my life as an aesthete since I first saw the Robbins show. Having never expected to see it again, I’m not surprised that doing so made me cry.

I’d planned to drive all the way from the Muny to Smalltown after the show, but it took so long for me to make my way out of Forest Park and onto the highway that I thought it would be imprudent to stick to my plan. Alas, the motel where I’d intended to stay was booked up, so I moseyed a bit further down the interstate and found a room at a Comfort Inn whose friendly night clerk assured me that I’d dodged a bullet (“You wouldn’t have wanted to stay at that place, hon—it’s a slum”). I slept fairly well, ate a tasty Waffle House breakfast, then drove on to Smalltown, where most of the surviving members of my mother’s family were in the process of assembling for our third reunion since 2015.

I attended the first of those reunions, after which I blogged about it at some length. This one was much the same, and I haven’t anything new to say save to mention with wonder that my Uncle Albert, the octogenarian patriarch of the Crosno clan, doesn’t look or act a day older than he did three years ago. David, my brother, smoked a pork loin to mouthwatering perfection and grilled a basketful of hamburgers, and we all ate our fill and talked each other’s ears off. In due course everybody exchanged hugs and hit the road, and David and I went to the living room to watch a couple of westerns, Open Range and Unforgiven, complete with commercials. Then I retired to the bedroom in which I slept as a boy, redecorated by David and Kathy since they moved into the house following my mother’s death but still as familiar as the face I saw in the bathroom mirror the next morning.

I attended the first of those reunions, after which I blogged about it at some length. This one was much the same, and I haven’t anything new to say save to mention with wonder that my Uncle Albert, the octogenarian patriarch of the Crosno clan, doesn’t look or act a day older than he did three years ago. David, my brother, smoked a pork loin to mouthwatering perfection and grilled a basketful of hamburgers, and we all ate our fill and talked each other’s ears off. In due course everybody exchanged hugs and hit the road, and David and I went to the living room to watch a couple of westerns, Open Range and Unforgiven, complete with commercials. Then I retired to the bedroom in which I slept as a boy, redecorated by David and Kathy since they moved into the house following my mother’s death but still as familiar as the face I saw in the bathroom mirror the next morning.

I arose on Sunday and went to Wal-Mart to buy some much-needed underwear, driving from there to the cemetery where my parents are buried. I got out of the car, walked to their grave, and stood in silence for a few moments, my head so full of memories that none of them could come to the fore save in inchoate bits and pieces. It seemed impossibly strange to look down at the grass under my feet and know what lay beneath it. Then I drove around town for a half-hour or so, taking in everything that had changed since my last visit.

I got back to the house just in time to greet the Merediths, Kathy’s clan, who had decided to assemble at 713 Hickory Drive the day after the Crosnos. We polished off the leftovers (of which there were plenty) and chatted cheerfully about all the things that large families chew over whenever they get together. The next morning I got up early, drove to St. Louis, flew from there to LaGuardia, and made my slow way to our apartment in upper Manhattan, where I spent a few minutes looking gratefully at the Morandi etching that hangs outside my bedroom and trying without success to sort out my feelings.

* * *

This is part of what I wrote about our last reunion:

I used to think that mine was an ordinary family. As the Stage Manager in Our Town says of Grover’s Corners, “Nice town, y’know what I mean? Nobody very remarkable ever come out of it, s’far as we know.” More and more, though, I find myself wondering just how ordinary it is to be so nice. It’s the dysfunctional families, after all, that get the ink these days, and it looks as though they’ve become the norm in postmodern America—though possibly not. Either way, I know how lucky I was to be born a Crosno. To come from such unfancy people, ordinary though they may be by the standards of the gilded city in which I now live, is to have a leg up in the long race of life, all the way from the starting gun to the finish line.

I still feel the same way, and I can’t put it any better now than I did then. Of all the myriad blessings whose sum is my life, none was greater than that of being born into an “ordinary” family from a small town located squarely—in every sense of the word—in the middle of America. All that I am, all that I’ve done since I left home to make my way in the world, is rooted in that soil.

I still feel the same way, and I can’t put it any better now than I did then. Of all the myriad blessings whose sum is my life, none was greater than that of being born into an “ordinary” family from a small town located squarely—in every sense of the word—in the middle of America. All that I am, all that I’ve done since I left home to make my way in the world, is rooted in that soil.

When you reach middle age, you not infrequently find yourself wondering how your life might have turned out had this or that detail been different. But once you cross the sixtieth meridian, you gradually cease to envision the nonexistent worlds in which you might have lived and start spending more and more of your time exploring the present, revisiting the past, and (on occasion) doing both things at once, as I did by going to the Muny to see Jerome Robbins’ Broadway. I have no shortage of unpleasant memories, but they don’t haunt me the way they used to: I’m far more disposed to push them aside and keep on adding to my still-growing store of experience. I continue to make new friends, almost all of them much younger than I am, and to visit new places and try new things. But I’ll also never stop going back to Smalltown, and to 713 Hickory Drive. While it is no longer my home—that is where Mrs. T is, now and forevermore—it will be a part of me for as long as I have the power to remember.

* * *

Angela Lansbury introduces scenes from Jerome Robbins’ Broadway, performed by the original cast on the 1989 Tony Awards telecast:

The last scene of Meet Me in St. Louis, directed by Vincente Minnelli and starring Judy Garland, Margaret O’Brien, Mary Astor, and Leon Ames:

A scene from “Walking Distance,” a 1959 episode of The Twilight Zone written by Rod Serling and starring Gig Young: