“Actors, take your official five, so that we can start at the top and work without stopping,” Debi Marcucci, the omnipotent stage manager and assistant director of Billy and Me, my second play, announced on Saturday morning. The stage emptied at once, and five minutes later, our first tech rehearsal got underway. I smiled, remembering a conversation I’d had five summers ago with Gordon Edelstein, who directed Shakespeare & Company’s production of Satchmo at the Waldorf, my first play. “You’re not going to watch this, are you?” he asked in apparent amazement when I showed up for the first tech rehearsal. “Watching tech is like watching paint dry.” Maybe so, but I was in the house for every minute of both rehearsals, and found them…well, not exactly thrilling, but completely involving. I’ve been watching tech—all of it—ever since.

“Actors, take your official five, so that we can start at the top and work without stopping,” Debi Marcucci, the omnipotent stage manager and assistant director of Billy and Me, my second play, announced on Saturday morning. The stage emptied at once, and five minutes later, our first tech rehearsal got underway. I smiled, remembering a conversation I’d had five summers ago with Gordon Edelstein, who directed Shakespeare & Company’s production of Satchmo at the Waldorf, my first play. “You’re not going to watch this, are you?” he asked in apparent amazement when I showed up for the first tech rehearsal. “Watching tech is like watching paint dry.” Maybe so, but I was in the house for every minute of both rehearsals, and found them…well, not exactly thrilling, but completely involving. I’ve been watching tech—all of it—ever since.

“Tech” is theater shorthand for the technical rehearsals—two consecutive twelve-hour-long days, in the case of the premiere of Billy and Me—during which the director, designers, and stage crew of a new show work together to develop, perfect, and rehearse the lighting, sound, and prop cues and scenic shifts that transform what happened in the rehearsal hall into what happens in front of a paying audience. The cast is present, too, rehearsing with deadly seriousness, but it is the collective will of the director and designers that prevails. If the sound designer needs to stop and repeat a scene because the phone didn’t ring at the right moment, you do so as often as is necessary to fix the problem. This is how a show starts to come into increasingly sharp focus for the very first time.

As I wrote in this space a year and a half ago, immediately after the second and last tech rehearsal for the production of Satchmo at the Waldorf that I directed at Palm Beach Dramaworks:

As I wrote in this space a year and a half ago, immediately after the second and last tech rehearsal for the production of Satchmo at the Waldorf that I directed at Palm Beach Dramaworks:

Tech is a grueling, painstaking, time-consuming process that requires infinite patience. If you’re a naturally impatient person—as I am, I regret to say—it can be tedious in the extreme. But if—as I also am—you’re the kind of person who has a taste for taking infinite pains, then it can be one of the most engrossing and pleasurable experiences that theater has to offer. It’s the Orson Welles part of stage directing: you get to pull out the toy box and spend hours and hours playing with it. You fuss endlessly and productively over every single lighting cue, making one part of the stage dark and another bright, with the lighting designer saying “Do you like it better this way, or this way?” over and over again like a demented ophthalmologist.

It was through watching Gordon’s tech rehearsals that I took the first step on the unexpectedly short road that led to my becoming a stage director in my own right. Not only did I learn what to do and how to do it from Gordon, but I learned the spirit in which it should be done. Spend a half-hour watching a tech rehearsal and you’ll come away knowing in your bones that theater is a collaborative art form. It is also, when done right, a civil art form, one in which everybody on and off stage says “please” and “thank you” and means it. “Quiet, please.” “Hold, please.” “Thank you very much.” These are the ceaselessly repeated refrains of tech, the tokens of mutual professional respect that are exchanged at some point in every transaction.

It was through watching Gordon’s tech rehearsals that I took the first step on the unexpectedly short road that led to my becoming a stage director in my own right. Not only did I learn what to do and how to do it from Gordon, but I learned the spirit in which it should be done. Spend a half-hour watching a tech rehearsal and you’ll come away knowing in your bones that theater is a collaborative art form. It is also, when done right, a civil art form, one in which everybody on and off stage says “please” and “thank you” and means it. “Quiet, please.” “Hold, please.” “Thank you very much.” These are the ceaselessly repeated refrains of tech, the tokens of mutual professional respect that are exchanged at some point in every transaction.

In Billy and Me this respect is made manifest, for the audience can actually see the stage hands rolling the set pieces into position as Nicholas Richberg, who plays Tennessee Williams, speaks the prologue to each act. “And now…I shall turn time forward,” he says after intermission, and three stage hands in period costumes come out of the wings and go to work. (You’d be surprised to know how much time and energy went into choreographng their straightforward-looking moves.) A minute or two later, we are in the living room of William Inge’s handsomely decorated Manhattan apartment, early in the morning of November 29, 1959, a few hours after the Broadway premiere of A Loss of Roses, Inge’s first flop. The result is, in the fullest possible sense of the phrase, a backstage play, one whose audience is privy to the creation of stage illusion.

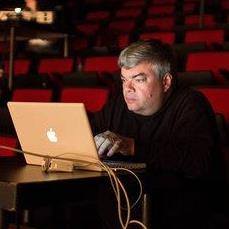

By now I am little more than a privileged bystander, a member of the audience with the best seat in the house, directly behind Bill Hayes, the director, and Paul Black, the lighting designer. I made my final revisions to the script on Saturday night, nipping out on the spot a half-page of superfluous dialogue, after which I put Billy and Me in the hands of my collaborators. From time to time I whisper suggestions to Bill, but mostly I’m content to sit and watch my script being transformed into Palm Beach Dramaworks’ production, learning lessons that I’ll put to use the next time I direct a play, whether by myself or somebody else. If there’s a better place to be, I’m damned if I know what it is.

By now I am little more than a privileged bystander, a member of the audience with the best seat in the house, directly behind Bill Hayes, the director, and Paul Black, the lighting designer. I made my final revisions to the script on Saturday night, nipping out on the spot a half-page of superfluous dialogue, after which I put Billy and Me in the hands of my collaborators. From time to time I whisper suggestions to Bill, but mostly I’m content to sit and watch my script being transformed into Palm Beach Dramaworks’ production, learning lessons that I’ll put to use the next time I direct a play, whether by myself or somebody else. If there’s a better place to be, I’m damned if I know what it is.

* * *

So how do I feel now, five days before opening night? Quite surprisingly calm. I like my play, and I love Bill’s staging of it. No doubt there are plenty of things that I will do differently should I ever get the chance to direct Billy and Me in the future, but right now I can neither see nor hear them. What is taking shape on stage is the play I meant to write, the story of two talented but troubled men who are trying to come to terms with what they are and what they’re meant to do with their lives. The results are more ambitious than Satchmo—one more act, two more actors—but not extravagantly so. I feel like I’ve taken a step of appropriate size toward…what? More playwriting, I certainly hope, for there are other stories I want to tell on stage.

So how do I feel now, five days before opening night? Quite surprisingly calm. I like my play, and I love Bill’s staging of it. No doubt there are plenty of things that I will do differently should I ever get the chance to direct Billy and Me in the future, but right now I can neither see nor hear them. What is taking shape on stage is the play I meant to write, the story of two talented but troubled men who are trying to come to terms with what they are and what they’re meant to do with their lives. The results are more ambitious than Satchmo—one more act, two more actors—but not extravagantly so. I feel like I’ve taken a step of appropriate size toward…what? More playwriting, I certainly hope, for there are other stories I want to tell on stage.

For the moment, though, I’m proud to have told this one, and proud above all to have had the all-consuming experience of working with Bill, Nick Richberg, Tom Wahl, Cliff Burgess, and our wonderful collaborators. They have taken my words and given them wings. May they soar come Friday night.